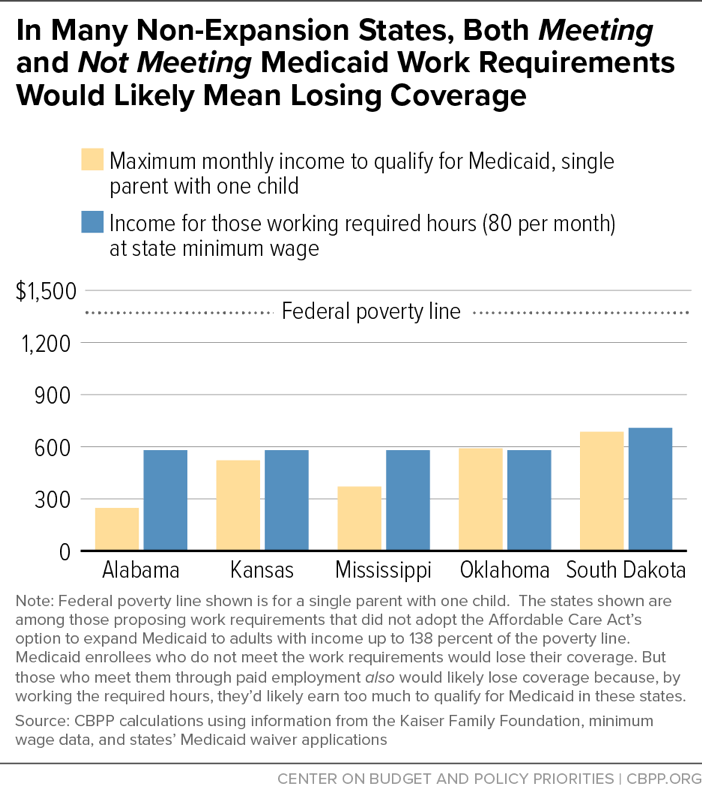

Some states that haven’t adopted the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) expansion of Medicaid to cover more low-income adults are now seeking or considering Medicaid waivers that would take coverage away from poor parents if they do not meet work requirements. In all of these states, substantial numbers of parents likely couldn’t meet the requirements, whether because of caregiving responsibilities coupled with a lack of affordable child care, because they work at unstable jobs that don’t provide enough hours of work every month, because of an illness or disability, or for other reasons. In many of these states, the proposals would also create a severe catch-22: even parents who did manage to comply with the work requirement would often lose coverage, since working the required number of hours at a minimum-wage job would raise their incomes above their state’s very low Medicaid eligibility limits.

Because of their impacts on coverage, access to care, and health, work requirement proposals — in expansion and non-expansion states alike — fail to promote the Medicaid program’s objectives, the legal standard that proposals are supposed to meet for the Secretary of Health and Human Services to grant waivers of Medicaid rules. But the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has nonetheless approved work requirement proposals in Arkansas, Indiana, Kentucky, and New Hampshire. Those all are states that have adopted the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid to cover low-income adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the poverty line.

Now, several states that have not expanded Medicaid are considering work requirements, with some of those proposals already pending at CMS (see Appendix). Non-expansion states generally do not offer Medicaid coverage to low-income adults without dependent children, and most of them cover only very low-income parents. Work requirements will almost certainly result in large coverage losses among these parents, with harmful consequences for their children’s health and well-being as well.

Supporters of Medicaid work requirements argue that the requirements will benefit enrollees and state economies by strengthening work incentives. The evidence for this claim, however, is weak; as discussed below, work requirements in other programs have not led to sustained gains in employment and incomes, and work requirements in Medicaid would likely make it harder for some enrollees to find or keep a job, since losing access to needed health care can make it harder for people to work or look for work.[1] But in many non-expansion states, there’s a further flaw in the logic underlying these proposals: even many enrollees who meet work requirements will still risk losing coverage. That’s because, in these states, Medicaid income limits are so low that they result in a “coverage gap,” where low-income parents may have incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid but too low to qualify for subsidized coverage in the ACA marketplaces. As a result, instead of being rewarded for working, parents who manage to comply with the work requirement could nonetheless lose their coverage, since working the required number of hours each month would cause their incomes to rise above their state’s strict Medicaid eligibility limits.

For example, to qualify for Medicaid in Mississippi, parents must have income below 27 percent of the poverty line, which is $370 a month for a single parent with one child. Under the state’s proposed Medicaid waiver, parents would have to work or engage in work-related activities for 20 hours a week to keep their coverage. Yet if parents were able to work 20 hours a week at the minimum wage, they would earn about $580 a month, too much to qualify for Medicaid in Mississippi. So, these parents could end up uninsured, because few low-wage jobs (especially part-time jobs) offer coverage, and their income would still be below the poverty line, which is the minimum income needed to qualify for subsidized coverage in the ACA’s individual insurance marketplace.[2]

Nor is Mississippi an isolated case. (See Figure 1 and Appendix Table 1.) In the median non-expansion state, a single parent with one child loses eligibility for Medicaid when the family’s income reaches just 43 percent of the poverty line ($590 per month.)[3]

CMS has indicated that it is troubled by the catch-22 aspect of these states’ proposals (though not by the harm that would result from Medicaid work requirements generally). In a recent media briefing, CMS Administrator Seema Verma said that she was having conversations with Mississippi policymakers aimed at having the state “try to make the proposal in a way that addresses that issue that there is not that cliff there.”[4] Days later, CMS notified Kansas — which limits Medicaid coverage to parents with incomes below 38 percent of the poverty line — that it couldn’t approve Kansas’ proposal to end coverage for people who aren’t employed or engaged in work-related activities. However, that letter also expressed a willingness to help the state identify a “workable approach to meeting the state’s goals.”[5]

There is, however, no such workable approach. In any state with a coverage gap for low-income parents, some parents who comply with a work requirement by working the required number of hours per month will still face the loss of their coverage, undercutting the already weak argument that these policies promote work. Meanwhile, with or without this catch-22 feature, implementing work requirements in non-expansion states will result in tens of thousands of low-income parents losing coverage, undermining the objectives of the Medicaid program by worsening their and their children’s access to care and health.

The ACA’s Medicaid expansion provides a pathway to coverage for low-income adults who weren’t eligible for Medicaid before health care reform. That includes adults who aren’t caring for a dependent child as well as parents whose income exceeds the pre-ACA eligibility level for low-income families, which was 64 percent of the poverty line in the median state in 2013. Most current non-expansion states had and still have income eligibility levels below that.[6]

Many adults benefiting from the expansion are low-wage workers without an offer of employer coverage. In 2014, only 37 percent of full-time workers with incomes below the poverty line and 59 percent with incomes between 100 and 250 percent of the poverty line had an offer of employer-sponsored coverage. For part-time workers, only 13 percent of those with incomes below poverty and 20 percent of those with incomes between 100 and 250 percent of poverty had an offer.[7]

The combination of Medicaid expansion and subsidized individual market coverage allows low-income workers to move across Medicaid, subsidized coverage in the individual insurance marketplaces, and available employer coverage as their incomes and circumstances change. But the Supreme Court’s decision making the Medicaid expansion a state option has led to 18 states having a coverage gap for workers with incomes below the poverty line, resulting in higher rates of uninsurance.[8] Overall, in states that expanded Medicaid by January 2016, some 6.5 percent of people were uninsured in 2016, compared to 11.7 percent of people in non-expansion states.[9] For people with incomes below the poverty line, the uninsured rate in non-expansion states (35.2 percent) was more than double the rate in expansion states (16.7 percent). More than 4 million people would gain coverage if all states expanded Medicaid, according to a recent analysis.[10]

The Medicaid coverage gap not only leaves large numbers of low-wage workers uninsured. It also creates work disincentives for very low-income parents enrolled in Medicaid. These parents may lose their health coverage if they start working or increase their hours or wages.

Non-expansion states seeking to promote work could adopt the Medicaid expansion, close the coverage gap, and eliminate the work disincentives the gap can create. Instead, states with coverage gaps for low-income parents — including Alabama, Kansas, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and South Dakota — are proposing to cut off coverage for very low-income parents who don’t satisfy work requirements.

In no state are work requirements likely to significantly increase employment. Studies of work requirements in other federal programs have found that they generally have only modest and temporary employment effects, largely failing to increase long-term employment or reduce poverty.[11] Meanwhile, by taking away coverage and impeding access to needed health care, work requirements in Medicaid may make it harder for some people to find or keep a job. Majorities of working people who gained coverage through the Medicaid expansion in Ohio and Michigan reported that it made them better at their jobs or made it easier for them to keep working, and majorities of non-working people reported that it made it easier for them to look for work.[12] Conversely, Medicaid work requirements may set off a vicious cycle for some working enrollees, where health problems that lead to job loss also lead to loss of coverage, making it harder to regain health and employment.[13]

But in non-expansion states with very low income eligibility levels for parents, such as Alabama, Kansas, and Mississippi, the basic logic of work requirement proposals breaks down, because even parents who manage to meet the requirement will still be at risk of losing coverage. Some of these proposals create literal catch-22s, where the income of parents who meet the work-requirement standard by working a sufficient number of hours will exceed the state’s Medicaid income limit, even if they earn only the minimum wage. (See Figure 1 and Appendix Table 1.) In other states, parents could theoretically satisfy the work requirement and keep their earnings below the Medicaid income cut-off, but they would risk losing coverage and becoming uninsured if they took a job with wages above the minimum wage or further increased their hours. (The Appendix provides a full list of the non-expansion states that are proposing work requirements.[14])

Most state proposals allow enrollees to comply with work requirements by volunteering or participating in job training, which would avoid the increase in income. But a work requirement policy under which parents can keep their coverage only by avoiding paid employment does not create work incentives. Moreover, as explained later in this analysis, many parents trying to comply by engaging in unpaid activities would likely still lose coverage.

Some parents would be eligible to receive transitional medical assistance (TMA) if they would otherwise lose eligibility for Medicaid due to new or increased earnings. But TMA doesn’t solve the catch-22, both because it’s time limited and because not all parents with earnings would qualify. In general, to qualify, low-income parents must have met Medicaid eligibility requirements in three out of the last six months before their income increased above the state’s eligibility limit.[15] Some parents, particularly new Medicaid enrollees, may not meet the requirement for prior coverage and thus may not qualify for TMA even if they fully comply with the work requirement after they enroll. Even for those who do qualify, many parents lose TMA coverage even before the 12-month eligibility period ends due to onerous TMA reporting requirements that apply during TMA’s last six months. Moreover, Alabama — a non-expansion state seeking a work requirement and which has the lowest income eligibility in the country (at 18 percent of the poverty line or $2,963 a year for a family of two) — is also seeking a waiver to limit TMA to six months.[16]

At a recent press briefing, Administrator Verma reiterated concerns with non-expansion state work requirement proposals, but also commented, “I think that when we work with those states, it’s our intent to be able to approve waivers for expansion states and non-expansion states.”[17] She has not explained how she thinks states like Kansas and Mississippi could address the catch-22 created by work requirement policies, but there are a few approaches that states might attempt. None of them change the basic fact that, in states that have not expanded Medicaid and have coverage gaps for low-income parents, many parents who meet work requirements, as well as those who do not, would be at risk of losing coverage.

Specifically, some states might try to build on TMA to provide additional transitional help to people whose incomes rise above Medicaid eligibility limits. But this approach has the same limitations as TMA — it offers only temporary help and may not cover all of those affected. Moreover, such proposals to try to address the catch-22 will make even temporary coverage unaffordable for many people if states design them to limit the proposals’ costs.

For example, South Dakota, which limits coverage to parents with incomes below 50 percent of the poverty line, recently released a work requirement proposal for comment that some have argued addresses the catch-22.[18] The state would provide parents whose incomes increase above Medicaid limits with premium assistance (i.e. subsidies to help them pay premiums for private coverage) for up to 12 months, following the 12 months of TMA. But after 24 months, parents would still be on their own, with no assistance to pay for health insurance.

Furthermore, South Dakota’s premium assistance program would not provide enough help to allow low-income parents to actually afford coverage and care. According to the state’s proposal, low-income working parents could use premium assistance, which would be set at the average per enrollee amount that the state spent on TMA in the prior year, to pay their premiums for employer coverage or for a qualified health plan in the individual insurance market. As discussed above, however, few parents employed in low-wage jobs would likely have an offer of employer coverage; and in the individual market, South Dakota’s premium assistance program would only cover the cost of a “bronze” plan for most parents.[19] Bronze plan deductibles average about $6,000, likely an insurmountable barrier for many people with incomes below the poverty line to afford care, and South Dakota would provide no assistance with cost sharing.[20]

A second possibility is that CMS might decide to allow non-expansion states to impose work requirements provided that individuals can satisfy the requirements through unpaid activities such as volunteering or job training as well as through paid employment. Most pending state proposals would permit this.

Such a work requirement, however, would create a disincentive for paid employment relative to other activities, since paid employment, unlike these other activities, would cause enrollees to lose Medicaid. Moreover, conditioning Medicaid on unpaid work could run afoul of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which requires that all individuals be compensated in an amount equal to at least the minimum wage in exchange for hours they work. States can operate “workfare” programs as part of their Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programs (SNAP), for example, but participants can be required to work only for a set number of hours based on their SNAP benefit divided by the higher of the state or federal minimum wage.[21] In these programs, participants are essentially working for their benefits at the minimum wage. But this isn’t possible in Medicaid, as the FLSA doesn’t allow states to count health insurance as wages.[22]

Even if labor laws are interpreted as allowing states to require people to volunteer to receive Medicaid, volunteer work is unlikely to offer most parents a viable way to keep their coverage, since suitable volunteer opportunities would not be readily available for most of those affected by work requirements. Agencies that utilize volunteers usually require them to have specific skills and go through training and vetting. There is no guarantee that low-income parents could find a suitable volunteer position allowing them to meet the work requirement.

Requiring enrollees to engage in job training raises similar problems. Current proposals don’t provide any assurance that suitable job training would be available to enrollees at no cost to them, or that the transportation and child care they would need to participate would be available, either. In fact, CMS guidance on work requirements specifically prohibits Medicaid reimbursement for job training, child care, or transportation.[23] Kentucky’s approved waiver, for example, merely calls on the state to “make good faith efforts” to connect enrollees to such supports.[24]

The catch-22 feature of non-expansion state work requirements undercuts the argument that these proposals will benefit enrollees or state economies by strengthening work incentives. But the larger problem with these proposals, as with expansion state proposals, is that large numbers of people will lose coverage because they do not meet the work requirement or satisfy the associated documentation and paperwork requirements. Those who will lose coverage include working parents who have difficulty documenting their work activities or meeting the required number of hours each and every month, as well as parents who might qualify for exemptions — because they have a disability, mental illness, or substance use disorder, for example — but are unable to provide the documentation required to prove it. [25] And — particularly in non-expansion states, where everyone subject to the requirements would be a parent or caregiver — they will include many parents who cannot balance child care responsibilities with working 80 hours or more every month.

None of the approved or pending Medicaid work requirements proposals guarantee child care assistance for enrollees who need it. Even with the additional federal funds for child care provided in the 2018 appropriations bill, it is estimated that only 1 in 5 eligible children nationwide will receive help.[26] Moreover, while most of the expansion states seeking work requirements are proposing to exempt at least parents of young children (and some would exempt all parents), the non-expansion state proposals generally fail to exempt more than a very small share of this group. For example, Alabama and South Dakota propose to apply work requirements to parents except those with a child under 1 year old. Without child care assistance, many parents will likely be unable to comply with the requirements through work or other activities.

Medicaid coverage improves access to care and health, and losing coverage will worsen access and health for these parents.[27] In addition, when parents lose coverage, their children’s health and development can be put at risk.[28] The data show that expansions of Medicaid eligibility for parents have led to increased enrollment of children who were already eligible for coverage. Increased enrollment has occurred not only when states expanded Medicaid under health reform but also in prior expansions of Medicaid eligibility for parents.[29] Research also confirms that gains in coverage for parents, and the associated gains for children, improve children’s access to care, such as well-child visits.[30]

Children also suffer directly when their parents lose coverage. Without health insurance, families’ financial security is at risk from increased medical debt. Financial insecurity doesn’t just affect adults; adverse effects that can result from poverty, such as toxic stress, can also negatively affect children’s development.[31] Children also suffer when parents can’t access treatment for such conditions as maternal depression.[32]

In short, children benefit when their parents can access the physical and mental health care that they need and can suffer when their parents are shut out of care.

Alabama’s income eligibility limit for parents is just 18 percent of the poverty line. The state comment period for its proposal to take coverage away from parents who don’t work closed on April 2, 2018, but the proposal hasn’t yet been submitted to CMS. Under the proposal, parents of children under 6 would have to work or engage in work-related activities for 20 hours a week while parents of older children would have to work at least 35 hours a week.[33]

Kansas’ income eligibility limit for parents is 38 percent of the poverty line. Its waiver proposal is pending at CMS. The state also sought to limit Medicaid coverage to three months in a 36-month period for people not meeting the work requirement and put a time limit of 36 months on those meeting the requirement. Parents in single-parent households would have to work 20 hours a week if they have a child under 6 and 30 hours if they have an older child. Parents in two-parent households would have to work a total of 35 or 55 hours a week depending on the age of the child. CMS rejected the time limit proposal on May 7, telling the state it would help it identify a “workable approach” to developing a work requirement.[34]

Maine’s income eligibility limit for parents is 105 percent of the poverty line, meaning that, while Maine has not expanded Medicaid, it does not have a coverage gap for parents. (Adults without children who have incomes below the poverty line are ineligible for both Medicaid and subsidized marketplace coverage.) In November 2017, voters approved a ballot initiative committing the state to expand Medicaid, but Maine’s governor hasn’t taken the steps necessary to expand. The state’s proposal to impose a work requirement on parents and other groups, including former foster care children and people whose coverage is limited to family planning services, is pending at CMS.[35]

Mississippi’s income eligibility limit for parents is 27 percent of the poverty line. Its proposal is pending at CMS. Parents would have to work or engage in work-related activities for at least 20 hours a week.[36]

Oklahoma’s income eligibility limit for parents is 43 percent of the poverty line. Recently enacted legislation requires submission of a waiver for a work requirement aligning with the requirement in SNAP that applies to adults without dependent children, which would require non-exempt parents to work 20 hours a week or lose their coverage.[37]

South Dakota’s income eligibility limit for parents is 50 percent of the poverty line. Its proposal is up for comment at the state level until June 19. Parents would have to meet certain milestones identified by the state and eventually work 80 hours or more a month.[38]

Tennessee’s income eligibility limit for parents is 98 percent of the poverty line, meaning that while Tennessee has not expanded Medicaid, it has only a small coverage gap for parents. State legislation requires the state to submit a waiver proposal with a work requirement for parents of children aged 6 and older. Tennessee wants to use unspent funds from its Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program to implement the waiver.[39]

Utah’s proposal, which is pending at CMS, would apply to enrollees in the state’s Primary Care Network (PCN). The PCN provides primary care services (not comprehensive Medicaid coverage) to a limited number of adults with incomes up to the poverty line. PCN enrollees would have to participate in job search or job training as a condition of eligibility.[40]

Wisconsin’s income eligibility limit for parents is 100 percent of the poverty line, and the state also covers adults without children with incomes up to that level, so while Wisconsin hasn’t expanded Medicaid, it doesn’t have a coverage gap for parents or childless adults. Its work requirement proposal, pending at CMS, would apply to adults without children. Months that these adults don’t work or engage in job training would count towards a 48-month time limit on benefits. Adults who reach the time limit would be ineligible for six months.[41]

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 |

|---|

| |

Medicaid Eligibility Level as a Percentage of Poverty |

Monthly Eligibility Level for a Single Parent with One Child |

Minimum Wage for 80 Hours |

|---|

| Alabama |

18% |

$247 |

$580 |

| Kansas |

38% |

$521 |

$580 |

| Mississippi |

27% |

$370 |

$580 |

| Oklahoma |

43% |

$590 |

$580 |

| South Dakota |

50% |

$686 |

$708 |

|