Chairman Hatch, Ranking Member Wyden, and members of the Finance Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify before you today. My name is Aviva Aron-Dine. I am a Senior Fellow and Senior Counselor at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a non-profit, non-partisan policy institute located here in Washington. The Center conducts research and analysis on a range of federal and state policy issues affecting low- and moderate-income families. Previously, I served in government in a number of roles, including as the chief economist at the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB), as Acting Deputy Director of OMB, and as a Senior Counselor at the Department of Health and Human Services, where my portfolio included Affordable Care Act (ACA) implementation and Medicaid, Medicare, and delivery system reform policy.

This Congress, and especially this committee, have important opportunities to strengthen health insurance markets in the near term and to continue expanding coverage and making health care better and more affordable over the longer term. But legislation could also easily take us backwards. In my testimony, I provide an overview of the progress made in expanding coverage and access to care under the ACA, the baseline against which future policy changes should be measured. I then discuss some of the challenges facing the individual market and how they could be addressed, and recommend some objectives for health care policy after these immediate issues are resolved.

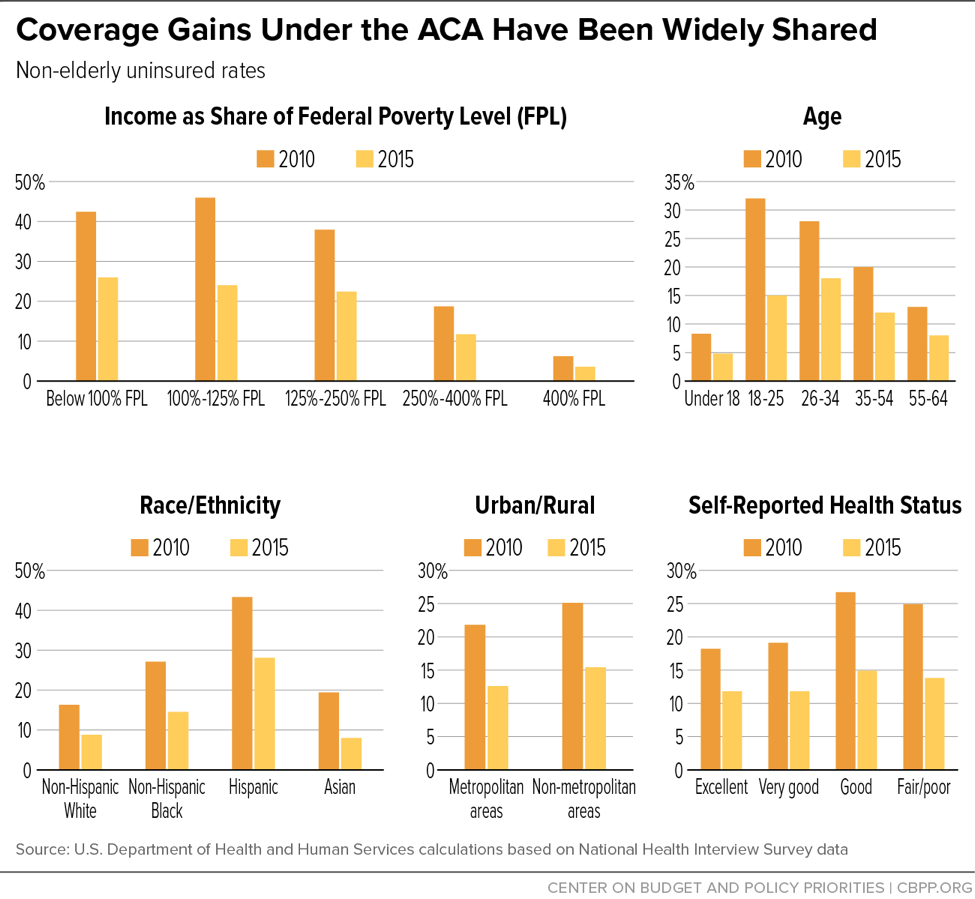

The most recent National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data show that the uninsured rate in early 2017 remained at its lowest level in history: about 9 percent, compared to 16 percent when the ACA was enacted in 2010.[1] The data also show that these dramatic coverage gains have been broadly shared across non-elderly Americans (seniors already had near-universal coverage through Medicare). As shown in Figure 1, uninsured rates from 2010 to 2015 fell by 35 percent or more for low-, moderate-, and middle-income Americans; for all age groups and racial and ethnic groups; across both urban and rural areas; and for people in both good and poor health.[2] These gains reflect the combined effects of the ACA’s coverage provisions, including the expansion of Medicaid to low-income adults, the creation of the health insurance marketplaces and subsidies for individual market coverage, allowing young adults to remain on their parents’ plans until age 26, and individual market reforms such as prohibiting insurers from denying coverage or charging higher premiums based on health status.

The quality of health insurance has also improved, including for people already covered through their jobs. For example, as of 2009, 59 percent of people with employer coverage had plans with lifetime limits on benefits, while almost 20 percent had plans with no limit on out-of-pocket costs, exposing them to catastrophic costs in the event of serious illness.[3] The ACA prohibits lifetime (and annual) limits on coverage and requires plans to cap consumers’ annual out-of-pocket costs.

In the individual market, quality improvements have been even greater. As of 2013, before the ACA’s major individual market reforms took effect, 75 percent of individual market health plans excluded maternity care, 45 percent excluded substance use treatment, 38 percent excluded mental health services, and up to 17 percent excluded various categories of prescription drugs.[4] Today, all plans subject to ACA rules — the large majority of individual market policies, excluding so-called “grandfathered” and “transitional” plans — are required to cover these essential health benefits. The ACA also ended pre-existing conditions exclusions, which meant that even when people with pre-existing health conditions were able to obtain individual market coverage, that coverage often excluded treatment related to their pre-existing condition. And individual market insurance now offers greater financial protection. Among families with individual market coverage, average out-of-pocket costs (counting premiums, deductibles, copays, and coinsurance) fell by 25 percent in 2014, when the ACA’s major individual market reforms and marketplace subsidies took effect.[5]

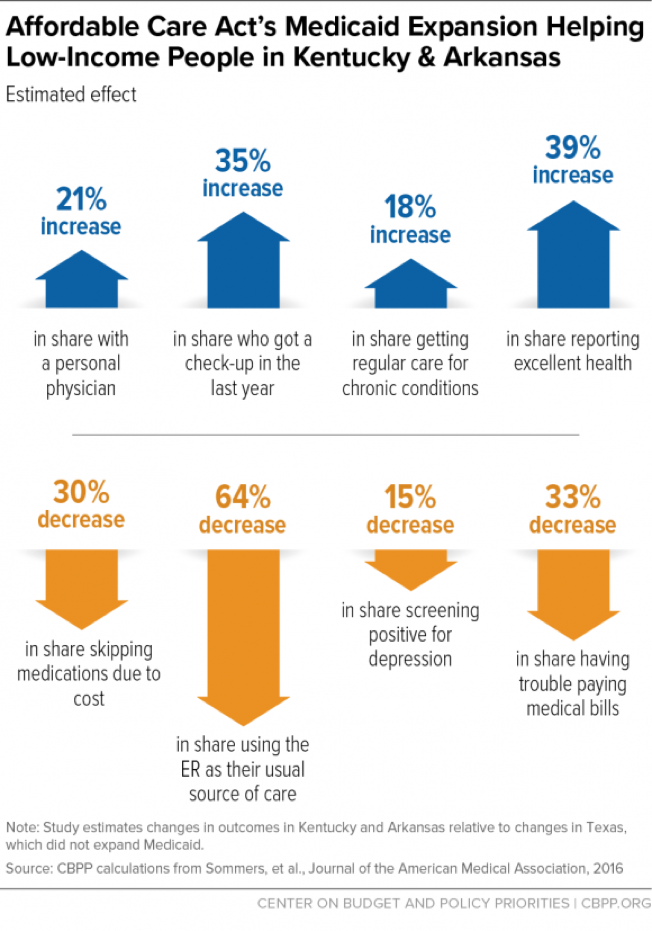

There is growing evidence that the expansion of and improvements in coverage under the ACA are translating into improved access to care and greater financial security. Some of the most in-depth research has focused on the impact of the ACA Medicaid expansion, with a group of Harvard researchers tracking changes in access to care, financial security, and health for low-income adults in Kentucky and Arkansas (which expanded Medicaid) versus Texas (which did not). As shown in Figure 2, this research has found sizable increases in the share of people with a personal physician, getting check-ups, getting regular care for chronic conditions, and reporting excellent health, and decreases in the share relying on the emergency room for care, skipping medications due to cost, struggling to pay medical bills, and screening positive for depression.[6]

Other research has found that Medicaid expansion increased access to preventive services, increased early diagnoses of chronic conditions, increased use of medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction, and reduced third-party medical debt collection and.[7] Research also finds that marketplace enrollees are accessing care at rates similar to people with employer coverage, that more than 80 percent of enrollees are satisfied with their plans, and that many marketplace (and Medicaid expansion) enrollees say their coverage is letting them access care they would otherwise have to forgo.[8] Meanwhile, national surveys show a roughly one-third decline in the share of the U.S. population who report forgoing medical care due to cost (since 2010), as well as increases in the share of people with a personal physician.[9]

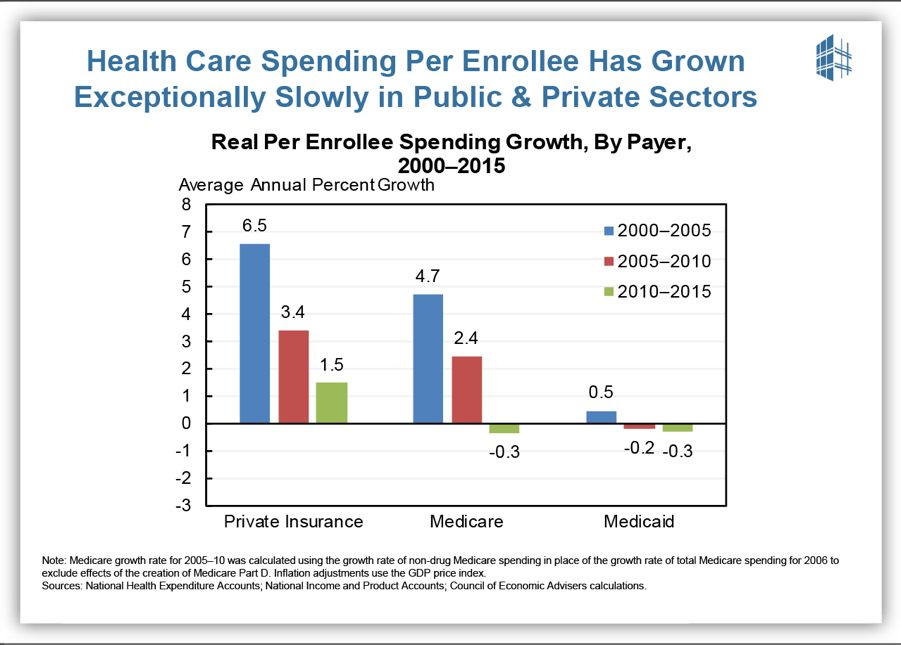

These expansions in coverage and access to care have coincided with a marked slowdown in per-enrollee health care cost growth — a slowdown to which the ACA has contributed, although it is certainly not the sole cause. As shown in Figure 3, per-enrollee spending growth since 2010 has been slower than over the previous decade in private insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid. This unexpected slowdown is yielding substantial savings for consumers and for the federal government. For example, family premiums for employer coverage averaged nearly $3,600 less in 2016 than if premiums since 2010 had grown at the average rate over the preceding decade. Meanwhile, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) now projects that total federal spending on major health programs will be more than $600 billion less from 2011 to 2020 than it forecast in January 2010, before the ACA was enacted, with lower-than-expected health care costs more than outweighing costs for expanded coverage.[10]

While the ACA is sometimes criticized for having focused on coverage expansions to the exclusion of cost concerns, in fact it contributed in important ways to this slowdown in health care cost growth. Most directly, the ACA instituted reforms to Medicare payment rates to more closely align them with costs; these reforms likely also had “spillover” impacts on health care cost growth for private payers.[11] The ACA also established incentives for hospitals to avoid unnecessary readmissions and prevent hospital-acquired conditions (such as infections); these programs have contributed to large declines in these adverse outcomes, improving care and reducing costs.[12]

Harder to quantify, but more important over the long run, the ACA created mechanisms for ongoing payment reform and experimentation in Medicare. Between the Medicare Shared Savings Program (the statutory Accountable Care Organization program created as part of the ACA) and payment models developed through the ACA’s Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, more than 30 percent of Medicare payments are now tied to “alternative payment models” that reward efficient delivery of high-quality care, rather than being made on a purely fee-for-service basis.[13] Medicare’s leadership has also helped catalyze similar efforts by private insurers and employers and state Medicaid programs, a number of which are engaged in large-scale shifts toward population- or episode-based payment.

Of course, health care costs remain a challenge for families, the federal budget, and states, with additional reforms needed to deliver better care at lower cost. But the ACA put in place a foundation for payment reform. Congress, with leadership from this committee, has already built on that foundation through the bipartisan Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA), and there are opportunities to do more — an issue I return to below.

Individual Market Trends and Policy Recommendations

In the near term, however, policymakers are appropriately focused on strengthening the individual market for health insurance, the source of coverage for roughly 6 percent of Americans and the part of the health care system that faces the most pressing challenges.

Since the ACA’s reforms took effect, individual market enrollment has grown, contributing to the overall decline in the uninsured rate. People with pre-existing conditions have seen especially large gains in individual market enrollment, reflecting the ACA’s provisions barring insurers from denying coverage or charging higher premiums based on health status.[14] Meanwhile, as discussed above, individual market plans offer more comprehensive coverage than before the ACA, and families’ total out-of-pocket costs are less (on average), thanks in large part to premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions.

In the early years of the ACA marketplaces, coverage expansions were accompanied by moderate premium growth, with benchmark premiums increasing by an average of about 5 percent per year from 2014 to 2016. In 2017, however, premiums increased much more rapidly, with benchmark premiums rising by an average of 22 percent in states with available data.[15] While most individual market consumers were protected from rate increases by the ACA subsidy structure (under which premium tax credits increase with premiums), rate increases were burdensome for a minority of enrollees with incomes too high to qualify for subsidies. They also raised questions about the health of the individual market. Did high rate increases indicate a deteriorating risk pool and health care claims spiraling out of control, or were they a transitional pricing correction reflecting the end of the ACA’s temporary reinsurance program and the fact that insurers in many states set initial premiums for the marketplaces that turned out to be well below costs?

With additional data available, it is now clear that these rate increases were primarily transitional, and the individual market at the start of 2017 was poised for greater price stability going forward. Three graphs tell the story.

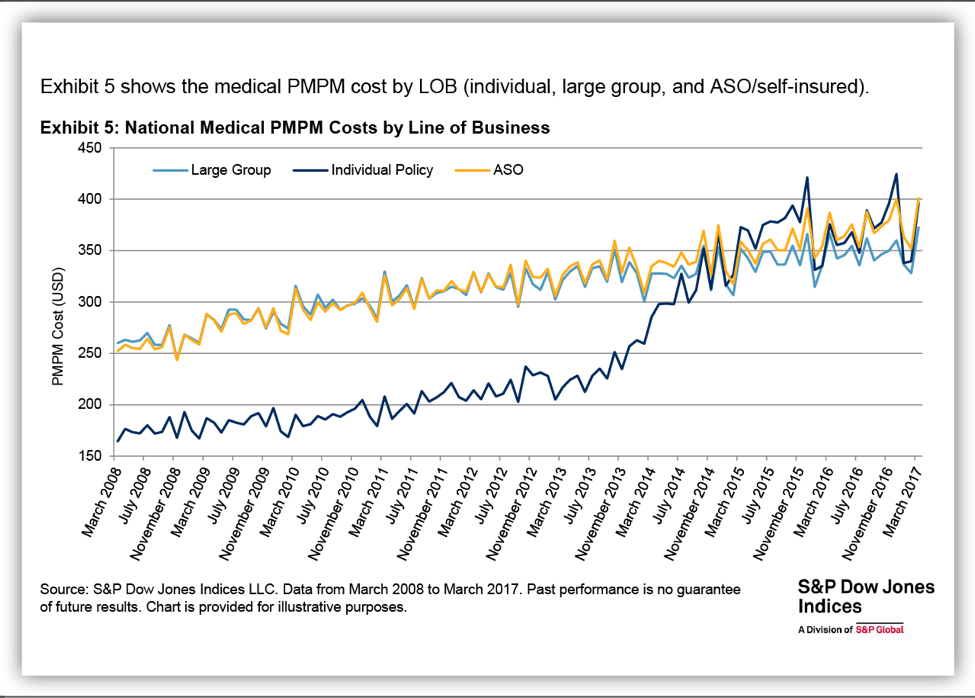

Figure 4, from the Standard and Poor’s (S&P) health care claims dataset, shows the path of per-member per-month health care claims costs in the individual market and in the large group and self-insured employer markets. As the figure shows, prior to the ACA’s reforms, individual market costs were far below costs in the employer market. That’s consistent with the fact that the pre-ACA individual market largely excluded people with serious health conditions, and (as discussed above) these plans covered far less than typical employer plans. Unsurprisingly, as the ACA’s individual market reforms took effect, individual market per-enrollee costs more or less caught up with employer plans costs (overshooting a bit through 2015, perhaps reflecting pent-up demand for medical care among new enrollees, but then coming back down). Critically, over the last couple years, growth in individual market claims has almost exactly kept pace with growth in employer plan claims, with slow year-over-year growth in both markets. That pattern is consistent with a market that is largely stable, and inconsistent with a deteriorating risk pool and spiraling costs.[16]

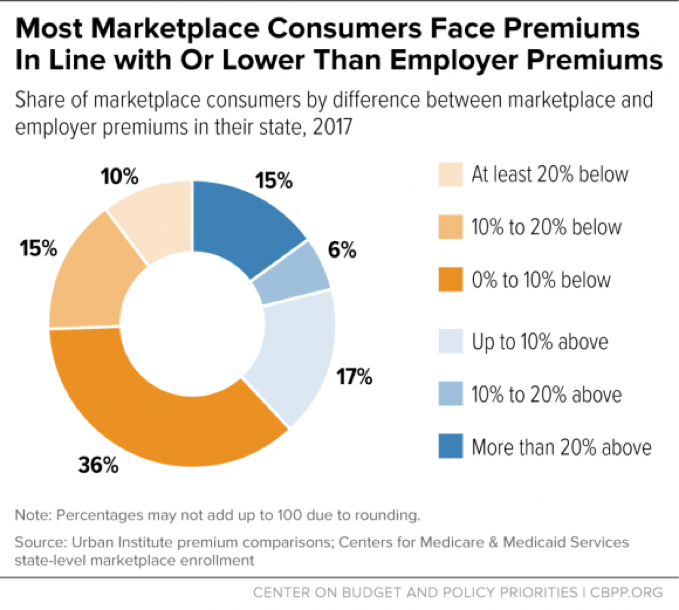

Figure 5, based on analysis by researchers at the Urban Institute, shows that premium increases in 2017 brought premiums in most of the country roughly in line with employer plan premiums. The Urban study compares 2017 benchmark premiums with average premiums for people with employer coverage, taking into account differences in enrollee age mix and plan generosity. As of 2017, the median marketplace consumer now lives in a state where marketplace premiums are almost exactly in line with employer plan premiums. In contrast, before the 2017 rate increases, the Urban researcher found that individual market premiums were well below employer plan premiums, on average.[17] It’s not surprising that discrepancy proved unsustainable, since employer plans and individual market plans are operating in the same health care system and face much the same costs.

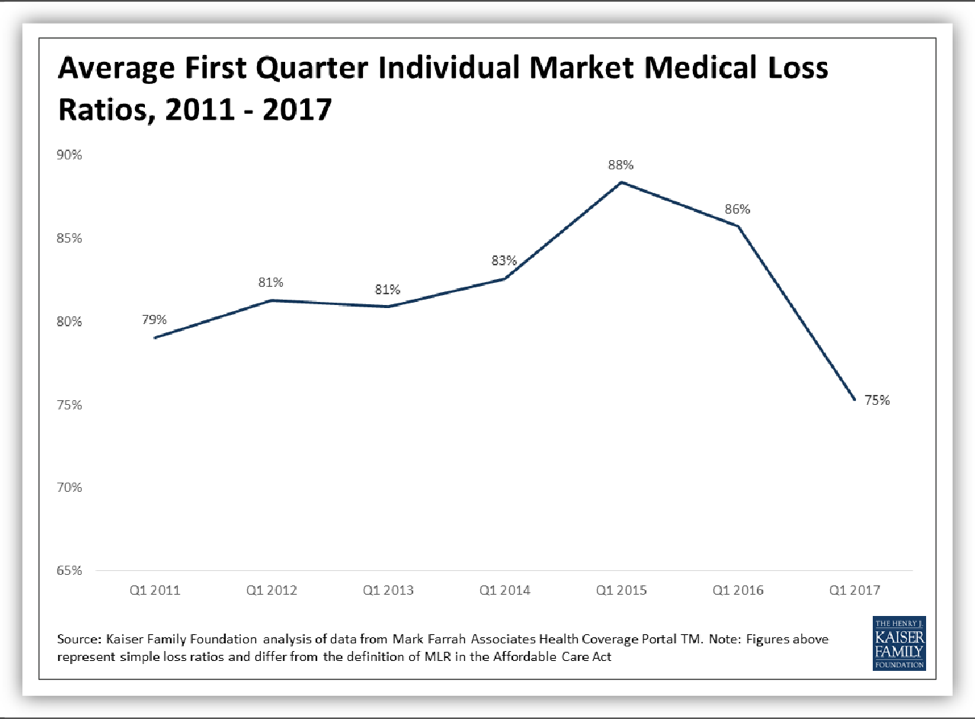

With premiums now roughly in line with employer premiums (on average), and with health care costs remaining in line with employer plan costs, one would expect individual market insurers’ finances to be stabilizing as well. And Figure 6, from the Kaiser Family Foundation, indicates this is indeed occurring.[18] In the first quarter of 2017, medical loss (claims-to-premiums) ratios in the individual market fell to slightly below their pre-ACA levels. Other data also suggest that many insurers will break even or earn profits on their individual market business this year.[19]

Greater financial stability for individual market insurers should be good news for consumers: all else equal, it would mean lower rate increases and growing competition going forward. And in fact, there is evidence that consumers would be realizing these benefits in 2018 — if it weren’t for federal policy uncertainty. In a number of states, individual market insurers have published their requested 2018 rate increases both with and without uncertainty around whether cost-sharing reduction (CSR) payments will be made, whether the individual mandate will be maintained and enforced, and other federal policy choices. Many of these insurers — including major health plans in Arizona, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee — have said that their premium increases would be in line with or below their expectation for economy-wide trend growth in medical costs, absent uncertainty about the continuation of CSR payments, individual mandate enforcement, or both.[20] Likewise, independent actuaries at Oliver Wyman estimate that, absent policy changes and uncertainty, average marketplace premiums would grow roughly with medical trend (plus an adjustment for the end of the health insurer tax moratorium).[21] Early this year, 96 percent of marketplace insurers surveyed by Oliver Wyman said they planned to continue offering plans in the marketplace in 2018, and 88 percent said that they planned to either maintain or expand their ACA marketplace footprint.[22]

Unfortunately, all else has not been equal, and consumers will mostly miss out on the benefits of a stabilizing market this year. Oliver Wyman projected that insurers would request additional rate increases ranging from about 10 to 20 percent due to the Administration’s repeated threats to stop reimbursing them for CSRs and additional increases averaging about 10 percent due to concerns that the individual mandate might not be enforced. Insurers have likely also priced in the risk — now a reality — that the Administration would sharply cut funding for marketplace outreach, which plays an especially important role in drawing healthier people into the market, and have likely also priced in the confusion created by the congressional repeal debate. (Remarkably, a Commonwealth Fund survey found that among uninsured adults who chose not to shop for plans on the marketplace last year, one-third attributed their decision at least in part to concerns that the ACA would soon be repealed.[23]) And almost without exception, insurers that are withdrawing from the ACA marketplaces for 2018 have cited federal policy uncertainty — arising from both the Administration’s actions and the congressional repeal debate — as a contributing factor, if not the main driver, of their decisions. Notably, Anthem linked its decisions to withdraw or reduce participation in several states directly to the risk that the Administration will stop CSR payments.[24]

Meanwhile, even setting aside the harm done by federal policy uncertainty, there is wide variation in the state of the individual market across the country. In many places, clarity about the rules of the road would likely suffice for stability. But some markets are struggling with additional challenges, including: small risk pools, in which a few unusually high-cost patients can make coverage less affordable for all or threaten insurers’ bottom lines; limited insurer or provider competition (generally dating from well before the ACA); and loopholes in federal or state law or state regulatory decisions that contribute to adverse selection in the individual market risk pool.

Over the past six weeks, governors, regulators, House members, and experts of both parties have weighed in on how to strengthen the individual market, with recommendations aimed at both undoing the damage done by federal policy uncertainty and addressing some of the market’s underlying challenges. It is striking how much overlap there is across these recommendations, as well as how straightforward many would be to implement: while some would require additional resources, most would not. Among the more common suggestions, with which I concur, are:

- Providing an explicit appropriation for CSR payments. As policymakers, regulators, and experts have explained, guaranteeing that CSR payments will continue is not a give-away to insurance companies; it is a critical protection for consumers, who will otherwise experience unnecessary rate increases and insurer withdrawals. Congress can and should resolve this issue for good, by providing an explicit, permanent appropriation for CSRs. Not only would such a measure not require a budgetary offset, it would actually protect the federal budget from tens of billions in extra premium tax credit costs that would result if insurers set prices year after year without knowing whether CSR payments will be made (or if the Administration discontinues these payments outright).[25] A temporary appropriation for CSRs would be far less beneficial, while an appropriation limited to one year would send a damaging message to insurers already planning for 2019, putting them on notice to prepare for the same federal policy uncertainty they experienced this year.

- Maintaining or increasing outreach and enrollment assistance. Going into the 2016 open enrollment season, only about half of uninsured Americans were aware of the financial assistance available to help pay for individual market coverage, even though an estimated 84 percent of the marketplace-eligible uninsured have incomes qualifying them for financial help.[26] The Administration’s recent decision to cut consumer outreach by 90 percent, and cut enrollment assistance through the Navigator Program by about 40 percent, will increase the number of people who go uninsured and forgo needed care or incur unaffordable medical bills. But it will also damage the marketplace risk pool, increasing average costs — and therefore premiums — since healthier consumers are the ones least likely to enroll without outreach. Notably, the cost of maintaining both outreach and enrollment assistance is low (the Administration’s funding cuts total less than $150 million), and both programs are financed largely out of marketplace user fees, not general appropriations.

- Enforcing the law, including the individual mandate. Outside experts from both parties have urged the Administration to enforce and administer the ACA as long as it remains the law of the land. This includes enforcing the ACA’s individual mandate, which discourages healthier individuals from going uninsured and shifting the costs of their unexpected emergency care onto others. While some have questioned the effectiveness of the ACA’s mandate, surveys and experiments show that it has a significant impact in motivating younger, healthier people to enroll in coverage.[27] The CBO has estimated that repealing the mandate would shrink the individual market risk pool by about a quarter and increase individual market premiums by about 20 percent, and rate requests from major insurers are consistent with that (with insurers in Maryland and Pennsylvania, for example, requesting additional rate increases of about 15 percent for 2018 to account for the possibility that the mandate might not be fully enforced).

- Reestablishing a federal reinsurance program. Reestablishing a federal reinsurance program (along the lines of the now-expired ACA reinsurance program) could benefit consumers in two ways. First, the subsidy provided by reinsurance flows through to unsubsidized marketplace consumers in the form of lower premiums. Second, by assuming some of the risk associated with high-cost claims, reinsurance diminishes insurers’ incentive to avoid covering high-cost individuals (such as by exiting the geographic areas where they reside), while also reducing uncertainty and thereby making it more attractive for insurers (especially smaller insurers) to participate in the marketplaces. Significantly reducing premiums through a reinsurance program would require meaningful federal resources (although the net cost of reinsurance is well below the gross cost, because a reinsurance program that lowers premiums also lowers federal premium tax credit costs). But addressing the risk associated with unusually high-cost claims could be done at much lower cost. (For example, a funded reinsurance program subsidizing claims above $1 million, along the lines of the budget neutral high-cost claims pool HHS established administratively as part of the risk adjustment program, would likely cost well under $1 billion per year.[28])

- Streamlining the process for 1332 waivers that improve market stability. In the absence of a federal reinsurance program, several states have already followed Alaska’s example and are seeking or developing waivers under Section 1332 of the ACA to obtain federal matching funds for their own reinsurance programs. The 1332 application process could be simplified to facilitate these and similar waivers that are consistent with the 1332 guardrails: they maintain or increase the number of people with health coverage, maintain or improve coverage affordability and comprehensiveness, and do not increase the federal deficit. In contrast, weakening these guardrails would harm individual market consumers by opening the door to changes that would increase the number of uninsured, place consumers on the hook for higher premiums or out-of-pocket costs, or allow plans to exclude key services that are especially crucial to people with pre-existing conditions.

Other suggestions from policymakers and experts also deserve consideration. For example, experts have suggested a number of approaches to expanding choice for people in low-competition areas by introducing some form of public option, whether by building on Medicare, Medicaid, the Federal Employer Health Benefit (FEHB) program, or another form of coverage. Congress should also consider tackling the problem of providers steering high-cost Medicare- or Medicaid-eligible enrollees to individual market plans. Such steering benefits the providers involved, who get paid at higher rates in commercial plans than in Medicare or Medicaid. But it often harms beneficiaries, who may lose access to important Medicare or Medicaid benefits and cost-sharing protections, and it may be doing meaningful damage to the individual market risk pool in some states.[29]

Some have raised the question of whether it is already too late for Congress to influence individual market rates and insurer participation for 2018. Unfortunately, it almost certainly is too late to fully reverse the damage done by federal policy uncertainty. Even if Congress acts quickly, insurers will not fully remove the uncertainty premium from their rates, and most insurers that have already decided to exit state marketplaces are unlikely to re-enter.

But this hearing is still timely, in that insurers in many or most states would still have the opportunity to lower their rates to reflect a federal commitment to make CSR payments. Even more important, a number of insurers (for example, Anthem in Maine) have made clear that they could still withdraw from state marketplaces for 2018 if they anticipate that the Administration will stop paying CSRs or cause other market disruption, while at least one insurer (Optima Health in Virginia) has stated that it might re-enter key markets if CSRs were guaranteed.[30] Quick action on a stabilization measure could lock in these insurers’ participation, not only by providing certainty around CSRs but by sending a signal that policymakers of both parties, with diverging views on the ACA, are committed to ensuring a strong individual market for consumers. As noted above, insurers are also already looking ahead to 2019; they will begin formulating preliminary rate requests early next year, and may start making decisions about marketplace participation even sooner than that. Without action within the next several months, consumers could miss out on the benefits of a stabilizing market for yet another year.

The ACA was never intended to be the final word on improving the health care system — far from it. But, new legislation should build on the progress made over the last several years in expanding coverage and access to care, not reverse it. The various repeal and replace bills considered by the House and Senate this year, as well as the repeal and replace plan offered by Senators Cassidy and Graham, violate that principle. Each would cause millions of people to lose coverage and make coverage worse or less affordable for millions more. That’s because each would effectively eliminate the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid to low-income adults; cap and cut federal Medicaid funding for seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children; sharply increase premiums and other out-of-pocket costs for people with individual market coverage; and weaken consumer protections that are especially critical to people with pre-existing health conditions.

As with individual market stabilization, recommendations issued over the past six weeks by governors, state regulators, members of Congress, and experts of both parties can help chart a different path forward. Rather than shifting costs to states and vulnerable populations by cutting funding for federal coverage programs, many of these proposals urge Congress to focus on reducing health care costs and improving the quality of care system-wide by continuing federal, and supporting state and private sector, delivery system reform efforts. For example, the health care proposal put forward recently by eight governors of both parties recommends “resetting the basic rules of health care competition to pay providers based on the quality, not the quantity of care they give patients,” while avoiding changes that “shift costs to states or fail to provide the necessary resources to ensure that [vulnerable populations] can get the care they need.”[31]

Congress already has a track record of working on a bipartisan basis, with leadership from this committee, to advance health care delivery system reform. The bipartisan MACRA legislation enacted in 2015 offers financial incentives for Medicare providers to participate in alternative payment models, while also adjusting fee-for-service payments based on quality metrics. Building on the tools provided by MACRA and the ACA, both Congress and the Administration could do more to promote development of alternative payment models; promote participation in these models by hospitals (not included in the MACRA incentive system); support states in shifting their Medicaid programs toward alternative payment models and instituting other reforms that promote better care coordination and increased use of preventive care; and support both state and private sector delivery system reform efforts through improved data systems, improved and more consistent quality measures, and other efforts.

In contrast, the proposals considered over the past year to cap and cut federal funding for Medicaid would not only cause millions of people to lose coverage, they could undermine ongoing state efforts to improve care and reduce long-term costs. Many of these efforts rely on up-front investments in care coordination, provider payment incentives, or improved behavioral health or other services. Under a Medicaid per capita cap, these types of investments would no longer be matched with additional federal dollars, and states facing large federal funding cuts would likely have to cut back on their own funding for these initiatives as well.[32]

Looking forward, these is also more to do to continue expanding coverage. During the debate over ACA repeal, critics of the law highlighted the fact that, even with the historic gains in coverage under the ACA, about 28 million Americans remain uninsured. The repeal proposals under consideration would have nearly doubled that number, but that does not diminish the imperative to reduce it. Fortunately, there are many opportunities to do so, including both federal legislation and state action.

Most straightforward, an estimated 4 to 5 million people would gain coverage if the remaining 19 states took up the ACA Medicaid expansion, as the majority of states, under the leadership of governors of both parties have already done.[33] As discussed above, Medicaid expansion has improved coverage, access to care, and financial security for low-income adults. And, as governors of both parties explained during the repeal debate, expansion has also strengthened state budgets, helped drive progress on major public health challenges like the opioid crisis, and had particularly large benefits for rural hospitals and rural Americans. (Rural Americans would also gain disproportionately if the remaining states expanded Medicaid, since the rural uninsured are disproportionately concentrated in non-expansion states.[34])

While many other options for expanding coverage are beyond the scope of this testimony and this hearing, others directly relate to the goals discussed above: strengthening the individual market and making individual market coverage more affordable. Of the remaining uninsured, about 8 million are eligible for but not enrolled in marketplace coverage.[35] Most in this group could qualify for subsidies, but, as noted above, many remain unaware of them, pointing to the importance of continued outreach. Others find marketplace coverage unaffordable even with the subsidies currently available, or unaffordable because they do not qualify for financial assistance. Targeted increases in tax credits and expansions in eligibility for subsidies could meaningfully reduce uninsured rates. They could also catalyze a virtuous cycle. As new research confirms, increases in subsidies for low- and moderate-income consumers not only have large effects on enrollment, they attract new enrollees who are significantly healthier, on average.[36] Thus, targeted increases in subsidies that make coverage more affordable for some could in turn help bring down premiums for others.