The Biden Administration’s decision to open HealthCare.gov to 2021 enrollment through August 15 is an important step to giving people access to comprehensive plans and financial assistance. But beyond the COVID-19 public health emergency, the Administration should make additional, permanent changes to make it easier for more people to enroll in coverage through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplaces. (See Figure 1.)

The Biden Administration, in its executive order on health care, directed relevant agencies to examine “policies or practices that may present unnecessary barriers to individuals and families attempting to access Medicaid or ACA coverage, including for mid-year enrollment….”[2] Federal open and special enrollment rules fit within this directive. The yearly open enrollment period (when anyone can newly enroll or change marketplace plans) is needlessly short, and people’s awareness of it remains low, even a decade after the ACA was enacted. After the end of open enrollment, people can access coverage only if they qualify for a special enrollment period (SEP), a process that is overly complex and restrictive. Millions of people experience the events that make them eligible for SEPs each year, yet few use the SEP to sign up for a plan. During the course of each year, more people leave the marketplace than join it — an imbalance that appears to be driving a seasonal drop in insured rates that did not exist prior to the ACA.

HealthCare.gov is essentially in the middle of a six-month open enrollment period because of the public health emergency. But looking ahead, the Administration should make permanent rule changes to simplify people’s pathways to the marketplaces, including by:

- Lengthening the annual open enrollment period. Reinstate a longer open enrollment period of at least 12 weeks, up from the current six weeks, to give people more time to sign up for or change plans each year.

- Create a “financial help” SEP. Allow people who are eligible for significant financial help to enroll in a marketplace plan at any time during the year.

- Create a “job loss” SEP. Grant someone who loses their job an SEP, even if they aren’t losing job-based health benefits.

More than one-third of people who are uninsured are already eligible for Medicaid or for premium tax credits in the marketplace.[3] While cost remains the top concern for many, some may be unaware that affordable coverage is available, or bureaucratic or other hurdles may have kept them from enrolling in or maintaining their coverage.

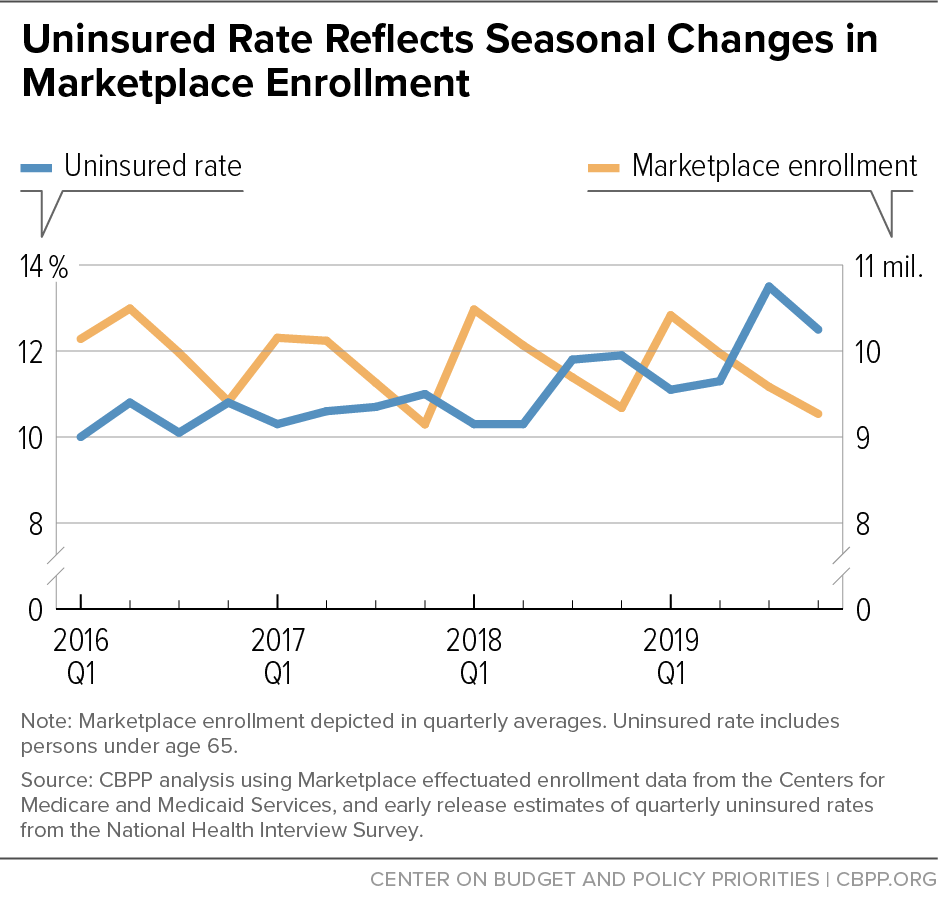

Enrollment deadlines and rules appear to be one of those hurdles. Many people who are eligible for special enrollment periods to enroll outside of the standard annual open enrollment period aren’t using them, possibly because they aren’t aware of them or because the system is too confusing.[4] Prior to the pandemic, marketplace enrollment consistently fell during the year by more than 1 million people. And the yearly decline in marketplace enrollment appears to have driven a troubling seasonal increase in the uninsured. The number of adults without coverage rose by more than 1 million between the first and fourth quarter of each year from 2016 through 2019, then fell by more than 1 million in the first quarter of the subsequent year (after marketplace open enrollment), National Health Interview Survey data show.[5] (See Figure 2.)

If the system were working well, marketplace enrollment would be roughly stable during the year, as the number of people enrolling in plans (because they lose job-based benefits or Medicaid, for example) would roughly match the number who leave (because they become eligible for Medicaid or get a job with health coverage). But the system is not working well.

The ACA marketplaces began operating seven years ago, and many people who are uninsured or accustomed to getting coverage from their job or other sources may not be aware of its rules and deadlines. In a 2018 survey, just one-quarter of potential marketplace consumers knew the open enrollment deadline.[6] Recent cutbacks in marketing and outreach under the Trump Administration likely exacerbated the lack of awareness.

Revamping rules for both open and special enrollment periods would help increase access to health coverage and reduce gaps in insurance when people experience changes in their lives. A more accessible enrollment structure would help even more people maintain coverage and avoid periods without insurance, when combined with improvements in marketplace financial assistance, such as the enhanced premium tax credits enacted in the American Rescue Plan.[7]

Nearly three-quarters of marketplace enrollees have annual incomes between 100 percent and 250 percent of the federal poverty line, or about $13,000 and $31,000 for an individual. People in this group have incomes that overlap with or are only a little higher than the incomes of people receiving Medicaid, which allows people to enroll in health coverage at any point during the year. And they may have children who are covered through the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which also has year-round enrollment. Many potential marketplace enrollees may therefore be accustomed to a continuous enrollment cycle and less familiar with the marketplace’s more restrictive structure.

Existing enrollment rules may pose challenges for low-income people for another reason. Research has shown that living in “chronic scarcity” (in which people lack money, time, and other basic resources) requires expending enormous mental effort to solve immediate problems, which makes decision-making more difficult and leaves less bandwidth to, for example, remember small details and remember to act.[8] At the same time, people with low incomes are eligible for significant financial help if they manage to enroll in a marketplace plan, making it all the more important to clear the hurdles they face.

As noted, awareness of the open enrollment period is low. In addition, it occurs during a period of the year (November 1 through December 15) when research shows people experience higher levels of financial and mental stress, making it possibly “the worst time of the year to require complex health insurance enrollment decisions.”[9] Lower-income people are likely to experience especially acute financial pressure between Thanksgiving and New Year’s Day, as expenses such as gifts and heating bills strain household budgets.

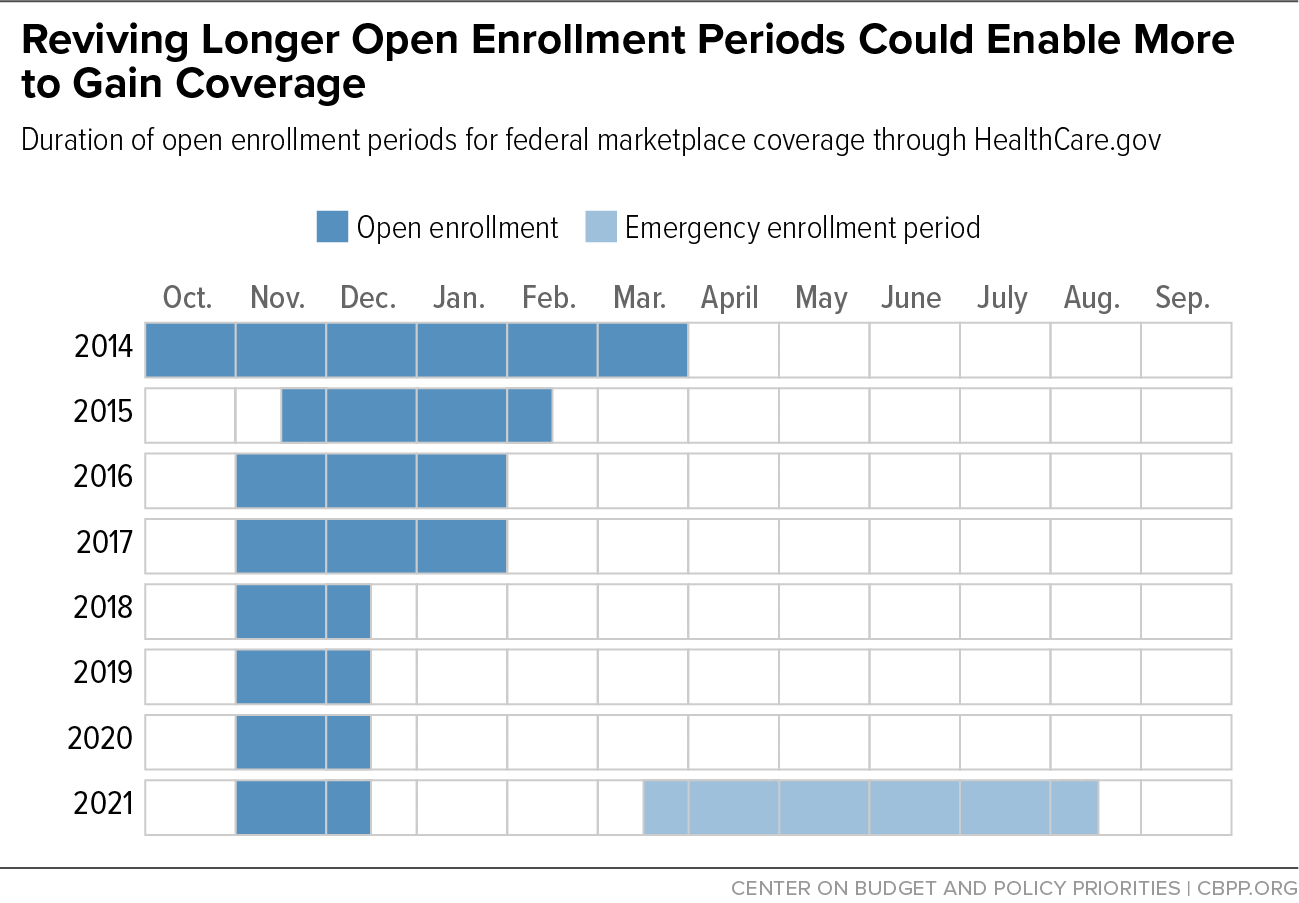

Many state-based marketplaces regularly provide longer open enrollment periods that stretch well into or through January.[10] The federal marketplace has also, at times, provided a longer annual open enrollment: people had five months to enroll for 2014, the first year the marketplaces began, and three months for several years after that with open enrollment closing at the end of January or in mid-February. Then, for the 2018 plan year, the Trump Administration cut this period in half, to just six weeks. (See Figure 3.) It also slashed spending on outreach, marketing, and enrollment assistance, which likely contributed to increased confusion or lack of awareness among the public.[11]

Reinstating a longer period, such as the November 1 through January 31 open enrollment that was in place during 2016 and 2017, would give more people time to enroll and allow for more expansive outreach efforts. It would also push the enrollment period past the stressful end-of-year period and give more people time to consider health coverage enrollment when they have less stress and more bandwidth.

For those who need coverage but miss the annual open enrollment period, qualifying for an SEP is the only way to access a marketplace plan. Dozens of different events trigger an SEP, such as having a baby and getting married, losing other health coverage, or moving out of the Medicaid “coverage gap” because their income rises above the poverty line.7 Usually, when one member of a family experiences one of these events, anyone eligible to sign up for a plan with that person (typically a spouse or children) is also eligible to enroll through the marketplace.

Two major problems plague SEPs. First, few of the people who could use SEPs are doing so —estimates range from 5 to 15 percent of those eligible.8 It’s easy to see why many people who are eligible for SEPs do not use them to enroll in a marketplace plan. To enroll in coverage using an SEP, people must know they have experienced an event that triggers one and then take action to claim it, usually within 60 days. They are required to complete the marketplace’s usual application and enrollment process. And, in the majority of states that rely on HealthCare.gov, people must also submit documentation before they can enroll using an SEP. They have to track down paperwork, such as a letter from an employer or insurer, that shows they experienced the event that triggered the SEP.

Second, some events when a person might otherwise seek coverage do not trigger an SEP. Losing a job, for example, doesn’t trigger an SEP unless a person is also losing health coverage through that job. And a drop in income — even one that qualifies someone for significant financial assistance in the marketplace — does not trigger an SEP if the person has been uninsured.

Failing to permit enrollment in a marketplace plan at these key moments, when someone might be more likely to apply and enroll in coverage, means missing opportunities to help them become insured. It also means that many people who are otherwise eligible for marketplace financial assistance have no way to access it when they need it most.

Notably, the emergency special enrollment period now in place at HealthCare.gov, and similar enrollment periods that states running their own marketplaces have made available during the COVID-19 public health emergency, simplify the normal structure in important ways. Uninsured people can access marketplace coverage during this time, while normally most SEPs are triggered when someone loses other health coverage. In addition, the emergency HealthCare.gov enrollment period allows people who might be eligible for another SEP due to loss of health coverage or other reason to more easily enroll in a plan, without having to know or document that they experienced another SEP-triggering life event. By March 31, more than 500,000 people had enrolled in marketplace plans during the emergency SEP that began in February, a substantial increase compared to the same period in prior years.[12]

Before the emergency SEP ends on August 15, it is critical to ensure that permanent policies are in place that emphasize bringing people into coverage rather than keeping them out. Adding two new SEP-triggering events for individuals found eligible for advance premium tax credits or who were uninsured and have become unemployed would improve the system.[13]

The financial assistance available through the ACA marketplaces has made health insurance more affordable for many people, yet the uninsured rate for lower-income people eligible for the most generous subsidies remains high: 14.1 percent of people with incomes between 138 and 250 percent of the poverty line are uninsured, compared to 3.1 percent for people with incomes above 500 percent of the poverty line.[14] At lower income levels, people are also more likely to experience financial problems related to medical bills or to delay medical care because of cost. Such problems are more prevalent among people who experience gaps in their health coverage.[15]

Many people with low incomes are eligible for a marketplace plan that costs nothing, or very little, in monthly premiums because the ACA premium tax credits reduce their costs. Under the recently enacted American Rescue Plan, in 2021 and 2022, people with incomes up to 150 percent of the poverty line (or about $19,000 a year for an individual) can enroll in a silver plan without paying anything toward the premium, and they are eligible for the most generous reductions in deductibles and other cost-sharing charges. People at slightly higher income levels are also eligible for assistance that cuts their premium costs significantly.[16] Four in five marketplace enrollees can find a plan for $10 or less per month.

For now, the emergency special enrollment period means that people who are determined to be eligible for financial help can also access a marketplace plan so they can receive it. But once the emergency SEP closes, the Biden Administration should establish a “financial help” SEP to allow people to enroll in a plan when they are determined eligible for advance premium tax credits, without having to experience or prove that some other SEP-triggering event has occurred.

A concern typically raised about year-round enrollment is that it will lead to adverse selection, which occurs when healthy people wait until they get sick to enroll in coverage. But, when people are receiving significant help paying their premiums, such that they can buy a plan for $0 or a relatively low monthly amount, it is unlikely that they are an adverse selection risk. It is far more likely that they have delayed getting coverage because they were not aware it was an option, did not know that it was affordable for them, or unwittingly missed an earlier enrollment deadline.

Some states already provide year-round enrollment to low-income people without any significant signs of adverse selection. In Massachusetts, people with incomes up to 300 percent of poverty (about $36,000 for an individual or $75,000 for a family of four) can generally enroll in marketplace coverage year-round.[17] New York and Minnesota allow year-round enrollment for people with incomes up to 200 percent of poverty who are eligible for coverage through their Basic Health Programs.[18] In contrast to the federal marketplace, Massachusetts consistently has stable or increasing marketplace enrollment over the course of the year.[19] And, while quarterly data on state uninsured rates are not available, all three of these states have overall uninsured rates among the lowest in the nation. A financial help SEP could be limited to people with incomes up to 300 percent of poverty, as in Massachusetts, to assuage any concerns that it could cause adverse selection.

Many people who lose their jobs qualify for the existing “loss of coverage” SEP because they also lose their employer-sponsored health benefits. But newly unemployed people whose employers didn’t offer coverage and who were already uninsured would not be eligible for an SEP under current rules, even though losing their job may make them, and their family members, newly eligible for premium tax credits.

A new SEP tied to job loss (irrespective of loss of coverage) would help more people access the marketplace. Outreach to this group could be simplified by sharing information about the SEP with people who apply for unemployment benefits. Such an SEP would likely lead to limited, if any, additional adverse selection, since most job separations are not related to health status.

Creating SEPs for financial help and job loss would make enrollment possible for people who miss the yearly open enrollment period because they are unaware of the deadline or are dealing with other challenges. These SEPs would also open the door to people who already qualify for existing special enrollment periods — in particular, because they are exiting Medicaid or job-based health coverage — but are confused and deterred by the SEP requirements.

These changes would also allow for additional forms of streamlined enrollment and targeted outreach. For example, tax filing season could be used as an opportunity to share health insurance information and offer streamlined enrollment opportunities to uninsured people eligible for zero-premium or low-premium plans. And children’s sign-ups for Medicaid or CHIP (which tend to occur outside the marketplace open enrollment period) could be used to reach out to their marketplace-eligible parents, or even to create streamlined enrollment opportunities using Medicaid and CHIP eligibility data.