The Senate’s changes to the House-passed health bill do not change the fact that the bill would take away coverage from tens of thousands of Alaskans and make coverage worse or less affordable for thousands more. As with the House bill, Alaska may be the single most harmed state under the Senate bill’s policies. That’s because the bill still reduces tax credits more deeply for Alaskans than for people in any other state while also still effectively ending the Affordable Care Act (ACA)’s expansion of Medicaid; still cutting Medicaid funding for seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children (in fact, cuts it even more deeply than the House bill); and still eliminating key benefits for Alaska Natives. All told, both bills would create a “perfect storm” of detrimental impacts that could hit Alaska harder than any other state.

But while the Senate bill’s overall impact would be particularly severe in Alaska, each of its damaging provisions would also harm other states — from its deep cuts in Medicaid to its tax credit reductions that would raise premiums and deductibles for millions of people nationwide. As Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski noted, trying to fix the health bill’s problems just for Alaska would mean “you [could] have a nationwide system that doesn’t work.”[1] As Senator Murkowski went on to explain (and as discussed further below), such an attempt would also fail Alaskans.

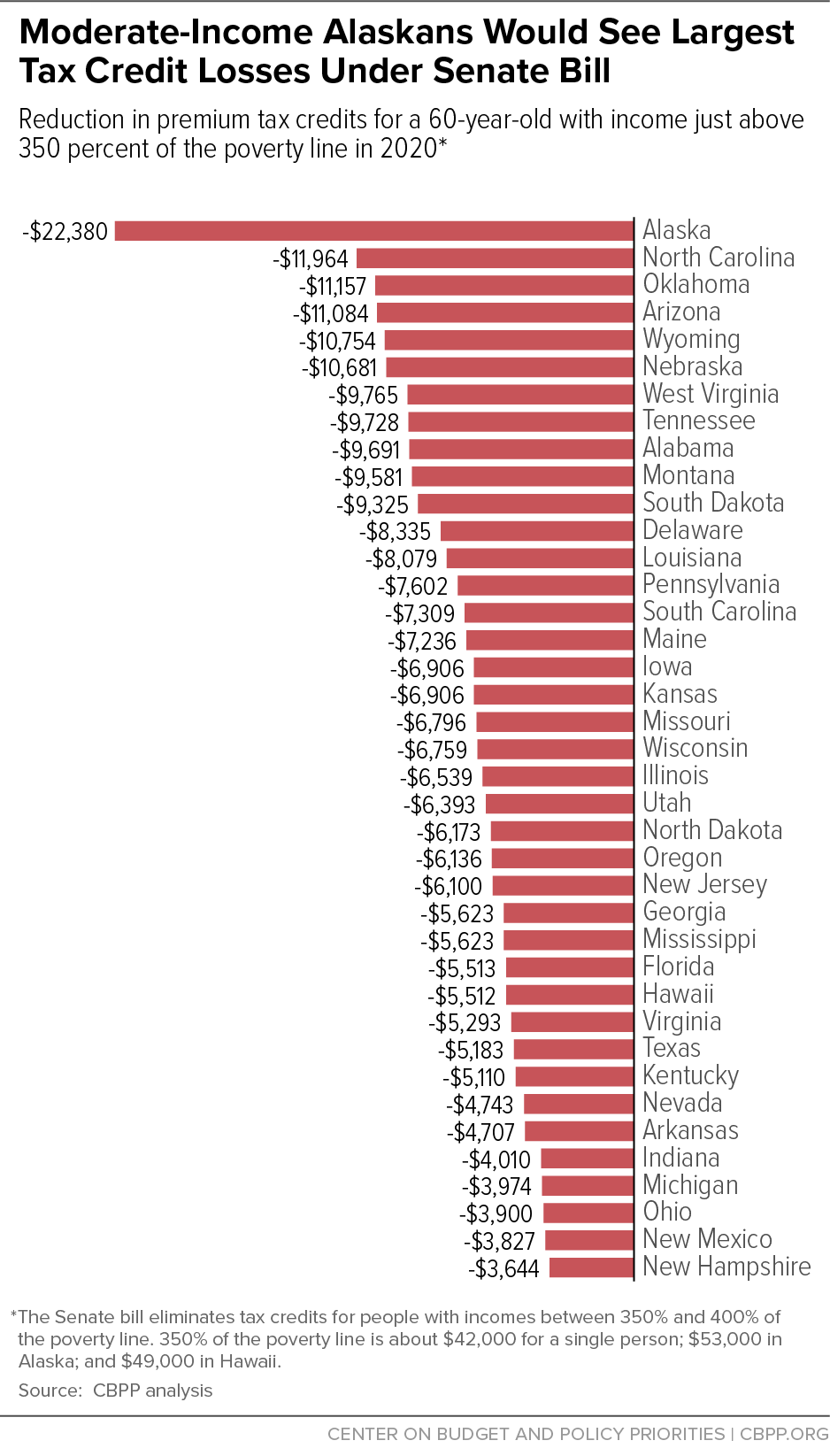

The House-passed bill slashed subsidies that help people afford individual market coverage, raising out-of-pocket costs by thousands of dollars for people who buy health insurance through the ACA marketplaces. While the Senate bill’s reductions to tax credits are structured differently, and are somewhat smaller on average, their broad consequences would be much the same: coverage and care would become far less affordable for moderate-income consumers. And while the Senate bill does restore the ACA’s approach of adjusting marketplace tax credits for local costs, it would still reduce tax credits most for people in high-cost states, and most deeply of all in Alaska.

That mainly reflects two provisions of the Senate bill.[2]

The Senate bill would eliminate premium tax credits for people with incomes between 350 and 400 percent of the poverty level, about $53,000 to $60,000 for a single person in Alaska. This change disproportionately affects people in high-cost states as well as older consumers. Because such consumers face higher “sticker price” premiums than others, they receive more financial help under current law, and they would see the largest spikes in their premiums absent financial assistance.

As Figure 1 shows, a 60-year-old with income just above 350 percent of the poverty line in Alaska would lose tax credits worth $22,380 in 2020 under the Senate bill. This is almost twice the impact in the next-most harmed state, and it would leave such a consumer with a premium equal to at least half of his or her income.[3] Tax credit reductions for younger Alaskans in this income range would be smaller but still sizable, and still much larger than for people in other states. For example, a 45-year-old Alaskan at this income level would lose over $9,000 in tax credits, compared to about $3,000 or less in other states. Even a 30-year-old Alaskan would lose tax credits worth over $6,000.[4]

While data on the number of marketplace consumers with incomes between 350 and 400 percent of the poverty line are not available, about 16 percent of Alaska marketplace consumers have incomes between 300 and 400 percent of the poverty line. That’s almost twice the national average and a higher share than in all but two other states.[5] Thus, in addition to facing deeper tax credit reductions, a larger share of Alaska marketplace consumers would likely be affected by this Senate provision. Marketplace consumers at these income levels are often entrepreneurs, self-employed people, and early retirees who depend on the individual market for health insurance coverage and rely on tax credits to afford it.

The Senate bill also reduces tax credits across the board by linking them to less generous coverage. Today, premium tax credits are based on the value of “silver plan” coverage: coverage with a 70 percent “actuarial value.” That is, tax credits are calibrated so consumers can afford plans that cover 70 percent of their medical costs (on average); consumers pay the remaining 30 percent through deductibles, copays, and coinsurance.

By contrast, the Senate bill would base the tax credits on the cost of a plan with an actuarial value of 58 percent — roughly equivalent to current “bronze plan” coverage. Consumers switching from silver to bronze plan coverage would see large increases in their deductibles: in 2016, the median bronze plan deductible (nationwide) was about $6,300, compared to about $3,000 for silver plans.[6] Alternatively, if consumers wanted to keep their current coverage, they would have to pay higher out-of-pocket premiums to make up for reduced tax credits.

Like the elimination of tax credits for people with incomes between 350 and 400 percent of the poverty line, this change would also impose larger costs on Alaska consumers than consumers in other states. In states where health costs — and hence premiums — are high, the difference in premiums between more and less generous coverage is also high. As a result, the reductions in tax credits from linking them to bronze rather than silver plan coverage will be larger in Alaska than in any other state. Equivalently, Alaskans would generally have to pay even more out of pocket to maintain their current coverage than consumers who live elsewhere.

For example, a 60-year-old with income at 300 percent of the poverty line in Alaska would have to pay $5,777 more in premiums to maintain her current coverage under the Senate bill, more than a similar consumer in any other state, and considerably higher than the $2,694 increase for a 60-year-old at 300 percent of the poverty line facing the national average benchmark premium.[7]

On June 27, the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services released a report finding that the Senate-passed health bill would cut Alaska’s federal Medicaid funding by $3.1 billion between 2020 and 2026, or 28 percent, an even deeper cut than Alaska would face under the House-passed bill.[8] The report concluded, “nearly 34,000 expansion adults could lose coverage entirely, and the remaining children, seniors, people with disabilities, and other adults covered by Medicaid are at increased risk for cuts.” The Department’s earlier report on the House bill noted, “the magnitude of the federal cuts are such that they may well affect Alaska’s ability to finance other State priorities such as education and infrastructure.”[9]

The Senate bill would still end Alaska’s Medicaid expansion, and it would cut total federal Medicaid funding for Alaska more than the House bill by 2026. Specifically:

-

The Senate bill’s treatment of the ACA Medicaid expansion would bring the same end result for Alaska as the House bill. Under the Senate bill, Alaska’s cost to maintain its expansion would rise by 50 percent compared to current law in 2021, 100 percent in 2022, and 150 percent in 2023, and would be five times its current law cost — an increase of $83 million per year — starting in 2024.[10] Alaska, which has faced persistent budget problems in recent years, would almost certainly find it fiscally unsustainable to continue its expansion, which has helped reduce the state’s uninsured rate from 18.9 percent in 2013 to 11.7 percent last year.[11]

But Alaska’s expansion would be at risk even before the Senate bill’s cuts took effect, because the bill would make it highly vulnerable to a legal challenge.

Alaska Governor Bill Walker expanded Medicaid by executive order, relying on a state law that requires Alaska to cover all groups that states must cover under federal Medicaid law, usually referred to as mandatory coverage groups. Despite the U.S. Supreme Court decision allowing states to decide whether to expand Medicaid, the Medicaid statute continues to list expansion adults as a mandatory group, so Governor Walker followed Alaska law and took up the expansion. A court challenge to Governor Walker’s executive order was rejected on the grounds that Alaska law requires the state to cover all mandatory coverage groups.

Under the Senate bill, however, the expansion population would no longer be treated as a mandatory coverage group. That would put Alaska’s expansion at grave risk of being overturned if, for example, any member of the Alaska legislature were to again bring suit to challenge the Governor’s authority to expand. Under Alaska law, the legislature must authorize the addition of an optional Medicaid coverage group, which would be unlikely, especially in the face of declining federal funding for the expansion. Thus, while the Senate bill threatens coverage for all 11 million people who have gained Medicaid coverage under expansion, it poses an especially immediate risk to Alaskans.[12]

- Like the House bill, the Senate bill would convert virtually the entire Medicaid program to a per capita cap. That means that rather than rising with need, federal Medicaid funding would be limited by a cap that would cover a falling share of a state’s actual costs over time. Cuts under a per capita cap would be deepest precisely when need is greatest, since federal Medicaid funding would no longer rise automatically in response to public health emergencies like the opioid epidemic. And the Senate bill would make the cuts even deeper by reducing the growth rate for the per capita cap beginning in 2025.

There has been some confusion over a supposed “Alaska carve-out” from the Senate bill’s per capita cap.[13] In fact, this provision merely exempts Alaska (and several other mostly rural states) from an additional cut — beyond those described above — that the Senate bill applies to some high-cost states. Alaska would be fully subject to the Senate bill’s Medicaid cap, including the lower cap growth rates starting in 2025.[14]

In 2014, before Alaska implemented its Medicaid expansion, 37 percent of non-elderly Alaska Natives were uninsured, second only to South Dakota for the highest uninsured rate among American Indians and Alaska Natives.[15] The ACA’s Medicaid expansion has enabled Alaska to provide an estimated 5,400 Alaska Natives with coverage, with Alaska Natives comprising about 37 percent of those gaining coverage under expansion. The non-elderly uninsured rate for Alaska Natives fell to 30 percent in 2015, even though Alaska’s Medicaid expansion was only implemented in September of that year; it has likely fallen further since then.[16]

Alaska Natives with Medicaid can use their coverage to receive care at Indian Health Services (IHS) and tribal operated facilities or with other providers who take Medicaid. Medicaid also pays the full cost for travel to such facilities, which is a critical benefit for rural Alaskans. The millions of new federal dollars that the Medicaid expansion has brought into Alaska have helped tribal facilities improve care and offer more services. Ending the expansion, as the Senate bill would almost certainly force Alaska to do, would thus disproportionately harm Alaska Natives.

The Senate bill would harm Alaska Natives who get coverage through the marketplace as well. Not only does it substantially reduce the size of the tax credits that people receive, but it also repeals the ACA’s cost-sharing reductions, which reduce deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs for lower-income consumers. This change would be especially burdensome for Alaska Natives because they qualify for more assistance than other consumers with similar incomes. (In particular, many Alaska Natives qualify for cost-sharing reductions that reduce their deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs to zero.) Alaska is second only to Oklahoma in the percentage of its marketplace enrollees who are American Indian or Alaska Native and qualify for this enhanced assistance.[17]

State Grants and Stability Funding in Senate Bill Do Not — and Could Not — Make Up for Its Devastating Effects in Alaska

The Senate bill includes $50 billion in funding for near-term efforts to stabilize the individual health insurance market and $62 billion for “long-term state stability and innovation” efforts. Some have suggested that these funds could compensate for the bill’s cuts to programs that help people afford coverage, or at least mitigate its reductions to tax credits and the resulting increases in premiums, for marketplace consumers.

In fact, the Senate bill’s marketplace stability funding is insufficient to keep “sticker price” individual market premiums from rising as a result of the bill. As a recent Brookings analysis shows, CBO’s analysis implies that the current population of marketplace enrollees would pay higher sticker price premiums on average for their current level of coverage under the Senate bill than under current law.[18] That’s primarily because the bill’s market stability funding would not make up for its repeal of the ACA’s individual mandate that people have health insurance or pay a penalty, which would lead healthier people to drop coverage, thereby increasing per-enrollee costs.[19] That is, rather than reducing sticker price premiums — and thereby compensating consumers for some of the reductions in tax credits — the Senate bill would increase premiums, exacerbating increases in total out-of-pocket premiums for consumers.

Meanwhile, the funds that would go to Alaska under the Senate bill are likely a small fraction of what Alaska would lose in federal Medicaid funding alone.[20]

But more important, even if the Senate dramatically increased the state grants for Alaska, they could not compensate for the structural damage that the Senate bill would do to Alaska’s Medicaid program and marketplace. Under current law, federal Medicaid funding will rise as needed to support Alaska in providing coverage for the more than 30,000 people covered through the Medicaid expansion and the other roughly 150,000 seniors, people with disabilities, families with children, and pregnant women covered through Alaska’s underlying Medicaid program.[21] As discussed above, the Senate bill would likely force Alaska to end its expansion altogether, and it would cap funding for the rest of Alaska’s Medicaid program. Not only does that approach shift billions in anticipated costs to Alaska over time, it also shifts all of the risk for unanticipated costs. Going forward, Alaska would be on its own to cover unexpected increases in per-enrollee Medicaid costs due to public health emergencies like the opioid crisis. Likewise, the Senate bill’s reductions to marketplace tax credits will make marketplace financial assistance less responsive to costs and need.

No fixed — and likely front-loaded — state grant program can compensate for these structural changes. As a result, whatever funding the Senate added to the Senate bill’s stability fund, the broad consequences for Alaska would remain the same as those identified in the Alaska Department of Health and Social Services’ reports: loss of coverage for many, worse coverage for more, and detrimental effects on other Alaska priorities from education to infrastructure.