Taking Away Medicaid for Not Meeting Work Requirements Harms Women

Medicaid is a critical source of health coverage for women. Nearly 40 million women get their health coverage through Medicaid, millions of whom became eligible due to the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) expansion of Medicaid to cover more low-income adults. Medicaid offers women essential health care services, including preventive care, family planning, and care for chronic physical and behavioral health conditions.

Now, the Trump Administration is letting states take Medicaid coverage away from people who are not working or participating in work-related activities for a specified number of hours each month. These policies will harm many women caring for children or other family members, as well as those with disabilities or serious illnesses who may not be exempt or may struggle with the bureaucratic hurdles to secure an exemption. Work requirements will also harm women who work hard in low-wage jobs with inconsistent hours and therefore may not meet work requirement standards each month.

The Administration is allowing states to impose work requirements on adult Medicaid enrollees other than those who are 65 or older, pregnant, or qualify for Medicaid because they receive disability benefits through Supplemental Security Income. In Arkansas, the first state to implement such a policy, over 18,000 Medicaid beneficiaries lost coverage in 2018 due to the new requirements While a federal court halted Arkansas’ policy, the Administration is continuing to approve similar policies in other states. Many of these policies require enrollees to document at least 80 hours of work or work activities (e.g., job training or volunteer work) per month, unless they prove that they qualify for limited exemptions.

Women Caring for Children or Other Family Members May Have Trouble Meeting Work Requirements

Many people with caregiving responsibilities will likely struggle to work the required hours every month. Although most women who could be subject to these policies work outside the home, women are more likely than men to be a caregiver to their children or family members. Caregiving responsibilities can make it harder to work outside the home, and even for those who are working, can make it harder to work 80 hours per month every month.

In states that haven’t expanded Medicaid, low-income mothers are among the primary targets of policies that would take Medicaid coverage away from adults who aren’t working, since they are among the small number of non-elderly adults who are eligible for Medicaid. Most of these states’ proposed work requirements would put mothers in a catch-22: if they don’t comply, they’ll lose coverage, but if they do comply, they’ll likely still lose coverage because their income will exceed their state’s very low Medicaid eligibility limit. (CMS has not yet approved this policy in a state that did not expand Medicaid, though several states’ proposals are pending.)

Even in states that have expanded Medicaid, mothers and other caregivers will be at risk of losing coverage. While some states’ work requirement policies exempt parents and caregivers, others exempt only parents of young children and have very limited exemptions for caregivers. Claiming these exemptions can be burdensome for mothers of older or adult children with special health care needs, who will have to prove that their child’s disability or special health care needs qualify. That will add one more burden for parents who already face major challenges and could compromise care for their children.

Women Will Also Lose Coverage for Other Reasons

Working women will also be at risk of losing coverage. Many working women enrolled in Medicaid are employed in industries where both employment and hours are volatile. Many workers in these industries report that their hours vary significantly from week to week. These jobs also feature little flexibility: any illness, family emergency, or child care or transportation disruption can lead to workers losing their jobs and experiencing gaps in employment.

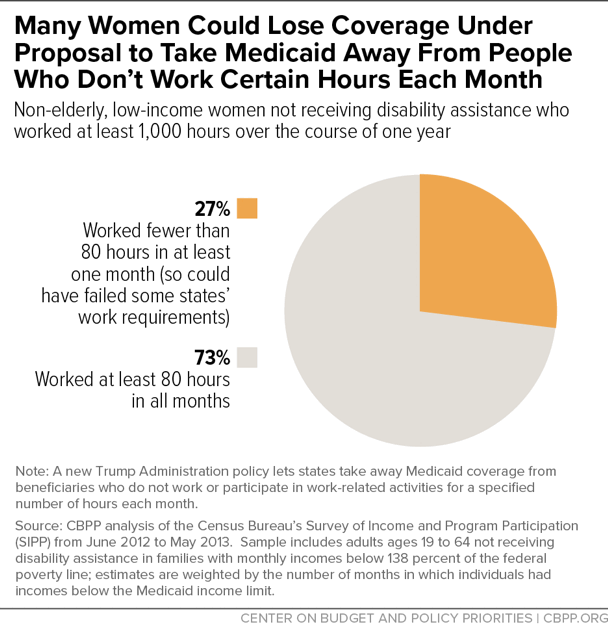

Reflecting these realities of the low-wage job market, 51 percent of low-income working women potentially subject to Medicaid work requirements could lose coverage for one or more months under an 80-hour-per month work requirement policy like the one that Arkansas is imposing. Even among women working 1,000 hours over the course of the year — meeting an 80 hours per month standard on average — 27 percent are at risk of losing coverage for one or more months because they don’t not meet the 80-hour requirement in every month (see chart).

Women with disabilities and serious illnesses are also at risk of losing coverage. These women could lose coverage if they don’t meet the criteria for limited exemptions, don’t understand that they qualify for an exemption, or are unable to provide the documentation proving that they qualify. For women who lose health coverage, lack of access to care will make it difficult to then get the documentation they need to prove they should be exempt. And many of the obstacles women face to holding a job — including caregiving responsibilities and lack of access to child care or transportation — may also make it difficult for them to overcome the bureaucratic hurdles required to prove they are exempt from these policies. Red tape and paperwork requirements have consistently proved to reduce enrollment in Medicaid, and studies of work requirements in other programs have found that people with disabilities, mental illness, and substance use disorders are disproportionately likely to be sanctioned and lose benefits, even though many should be exempt.

Losing Coverage Will Worsen Women’s Access to Care

Women who lose coverage as a result of these policies could face significant harm. Studies have found that Medicaid expansion increased the share of people with a personal physician, the share getting check-ups, and the share getting recommended preventive care such as cholesterol and cancer screenings, and decreased the share delaying care due to cost, skipping medications due to cost, or relying on the emergency room for care. State policies that take away coverage from people not meeting work requirements could reverse a large share of these gains.

Losing access to care would be especially harmful for the nearly half of all women who have an ongoing condition requiring regular monitoring, care, or medication. For example, women are increasingly affected by the opioid crisis: twice as many women died from opioid overdoses in 2016 as in 2007. Taking Medicaid coverage away from women who aren’t working could restrict their access to needed substance use disorder treatment and recovery services.

This is part of why groups like the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Medical Association, and American Academy of Family Physicians oppose Medicaid work requirements, as do the National Women's Law Center, Planned Parenthood, the National Partnership for Women and Families, and other groups that advocate for women and families.