WIC — the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children — provides nutritious foods, counseling on healthy eating, breastfeeding support, and health care referrals to millions of low-income women, infants, and children at nutritional risk.[2] WIC is extremely effective, extensive research shows: WIC participation improves low-income families’ nutrition and health at a critical stage of development, leading to healthier babies, more nutritious diets, better health care for children, and higher academic achievement for students.[3] In addition, our new analysis shows, per-participant costs and the number of WIC participants are remarkably stable (see Figure 1), and WIC spending as a share of the economy has fallen to its lowest level since before 1997.

WIC has grown substantially from its modest beginning in 1974, when it served just 88,000 participants. Its growth came in two distinct periods. First, for more than 20 years, limited funding prevented some eligible women and young children from receiving WIC benefits. Because WIC was so effective, however, Congress on a bipartisan basis increased funding over time to reach more eligible applicants. Second, starting in 1997, WIC has been “fully funded” — that is, it has received sufficient resources to serve all eligible individuals who apply and has no longer needed to turn away eligible applicants due to funding constraints.[4] WIC now serves more than 7 million women, infants, and children each month.

Since its full funding began in 1997, WIC’s participation and costs have been remarkably stable.

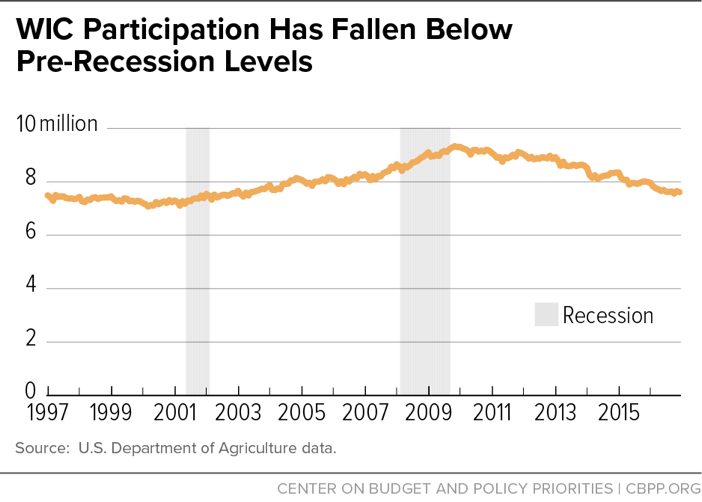

- WIC participation has grown very little since 1997. The number of WIC participants rose at an average annual rate of just 0.2 percent after full funding began (from 7.4 million low-income women, infants, and children in 1997 to 7.7 million in 2016). As the economy improved following the recession, the number has fallen for several years in a row. WIC participation is consistent with broader economic and demographic trends.

- WIC helps reduce economic hardships for women and young children who receive benefits when the economy falters and poverty and unemployment rise. Participation and spending grew during the recent recession, as WIC responded to increased poverty and food insecurity. But the economy has since improved, and participation has returned to its pre-recession level.

- Slowly over many years, WIC has reached more eligible families, reflecting program simplifications and better customer service. The participation rate among eligible women and young children in 2013 — 60 percent — was 2 percentage points higher than in 2000.

- The number of participating women and young children has risen and fallen with the number of low-income women and young children likely to be eligible.

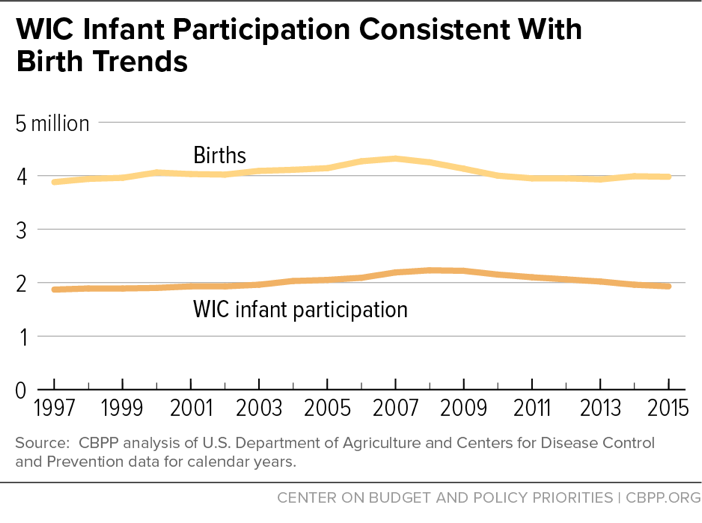

- Trends in the number of infants participating in WIC each year closely match trends in the number of births: both rose gradually after 1997, with births reaching their recent peak in 2007 and WIC infants reaching their peak about a year later, before both then fell. Births declined by 8 percent between 2007 and 2015 and WIC infant participation fell by 13 percent between 2008 and 2015.[5]

- Although some states have set Medicaid eligibility higher than the WIC income limit, “adjunctive eligibility” — which confers eligibility to certain individuals who receive Medicaid and their family members in order to streamline WIC eligibility determinations — apparently has affected WIC participation to only a very small degree.

- Per-participant WIC costs have not grown. Because per-participant WIC costs for food and nutrition services have remained steady, the decline in participation in recent years has returned annual WIC spending to below pre-recession levels even in nominal terms ($5.95 billion in 2016, compared with $6.19 billion in 2008). WIC spending as a share of the economy is at its lowest level since before full funding.

- WIC food costs — the bulk of WIC’s overall costs — have grown more slowly than food prices in grocery stores.

- Real per-person WIC funding for nutrition services and administration has remained steady, growing only with inflation, for 27 years.

The rest of this report explains each of these factors in more detail, focusing on the full funding period since 1997. All told, WIC is a stable program that expands and contracts modestly with changes in the economy and birth rates, and includes strong cost controls.

WIC receives “discretionary” funding through the annual congressional appropriations process, competing with other programs under the current budget caps, as reduced by sequestration.a Congress authorizes a specific amount of funding each year and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) gives each state a grant to operate the program. Most other federal nutrition programs, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps) and the National School Lunch Program, operate as “entitlements,” so that their budgets automatically expand to ensure that all eligible applicants can receive benefits. With WIC, by contrast, the number of families that can receive benefits depends upon the size of the annual appropriation, the cost containment savings WIC achieves, and the cost of operating the program.

For many years after policymakers established WIC in 1974, Congress did not provide enough funding to serve all eligible low-income women and children who sought benefits. State agencies provided benefits to those with the most serious health conditions and created waiting lists for other eligible individuals.b Over time, with bipartisan support, Congress gradually raised the annual WIC appropriation with the goal of eventually providing enough funding each year to serve all eligible low-income women, infants, and young children who applied for benefits.c The program reached this “full funding” level by 1997, and Administrations and Congresses of both parties have continued to fully fund WIC since then to meet projected needs.

Even with “full funding,” some eligible people don’t participate. WIC served about 60 percent of all eligible women, infants, and children in 2013, USDA estimates. Moreover, the uncertain appropriations process sometimes affects program operations. When, for example, Congress adopts a short-term continuing resolution and does not finalize the annual funding level until well into the fiscal year, state WIC directors don’t know how much funding they’ll eventually receive and may temporarily scale back operations — by, for example, not filling staff vacancies — until they know. Similarly, the federal government shutdown in the fall of 2013 apparently caused confusion among some eligible families who may not have applied for WIC due to inaccurate media reports that WIC was closed (even though it had enough funds to continue operating).

a The overall cap on non-defense appropriations, as reduced by sequestration, was frozen in 2017 and will decrease by $3 billion in 2018, meaning a loss in purchasing power in both years and bringing the 2018 total 16 percent below 2010 in inflation-adjusted terms. Within this eroding total, WIC competes for funding with a wide range of other non-defense discretionary programs, including education, job training, national parks, law enforcement, scientific and medical research, veterans’ health care, and child care.

b WIC rules establish seven priority categories. In general, priority goes to persons with medically based nutrition risks over dietary-based nutrition risks, to pregnant and breastfeeding women and infants over children, and to children over postpartum women. See 7 C.F.R. § 246.7(e)(4).

c Support for expanding WIC was driven in part by research demonstrating the program’s effectiveness. The introduction of competitive infant formula rebates accelerated this expansion by reducing the government’s cost of providing formula and enabling each annual appropriation to serve more low-income participants. For more information about the importance of infant formula rebates, see Steven Carlson, Robert Greenstein, and Zoë Neuberger, “WIC’s Competitive Bidding Process for Infant Formula Is Highly Cost-Effective,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated February 17, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/wics-competitive-bidding-process-for-infant-formula-is-highly-cost.

Means-tested programs like WIC are designed to provide a safety net for families when they struggle to make ends meet.[6] By providing supplemental food and freeing up resources for other necessities, like rent and medicine, nutrition assistance programs ease food insecurity and other hardships. During economic downturns, unemployment rises and more families need assistance. By growing to meet the greater need, programs like SNAP and WIC help provide a safety net during downturns.

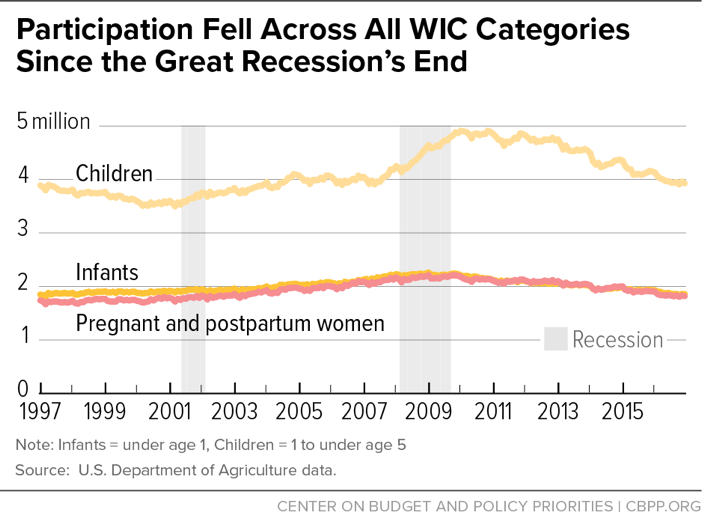

WIC participation grew during the recession, but it has since returned to pre-recession levels. (See Figure 1.) Since Congress started fully funding the program in 1997, through 2016 (the most recent year for which we have data), the number of WIC participants rose at an average annual rate of just 0.2 percent (from 7.4 million low-income women, infants, and children in 1997 to 7.7 million in 2016). Most recently, WIC participation has fallen six years in a row, dropping 18 percent from its peak in August 2009. The declines have occurred in each WIC category: pregnant and postpartum women, children (age 1 to 4), and infants (from birth to age 1), among whom participation has dropped 19 percent from the peak in October 2008. [7] (See Figure 2.) Participation has continued to decline over the first quarter of fiscal year 2017.

WIC participation has risen very gradually over time. Between 2000 and 2013 (the most recent year available), the participation rate — the share of eligible people who receive benefits — rose by 2 percentage points, from 58 percent to 60 percent.[8] Participation rates are highest among infants, and higher among women than young children. The slight increase in the participation rate may reflect efforts by state and local administrators to offer more flexible scheduling and clinic hours that better accommodate working mothers.

The economy affects WIC funding and participation. Because WIC participation was limited by WIC’s budget for much of its early history, the economy had little effect on the number of participants in those years. Economic conditions became more important once Congress began providing full funding. The modern WIC program typically expands when the economy shrinks and contracts when it grows, USDA research suggests.[9] During recessions, WIC responds to increased poverty and food insecurity, and participation grows along with the number of low-income families. When the economy improves, fewer families need help and WIC participation falls.

The economy also influences the number of births, with birth rates likelier to be stable or rise in a healthy economy and fall in a weak economy. Birth trends, in turn, strongly influence WIC participation because WIC is limited to pregnant or postpartum women and very young children. Changes in WIC participation since 1997 are consistent with changes in the number of low-income women and children as well as births.

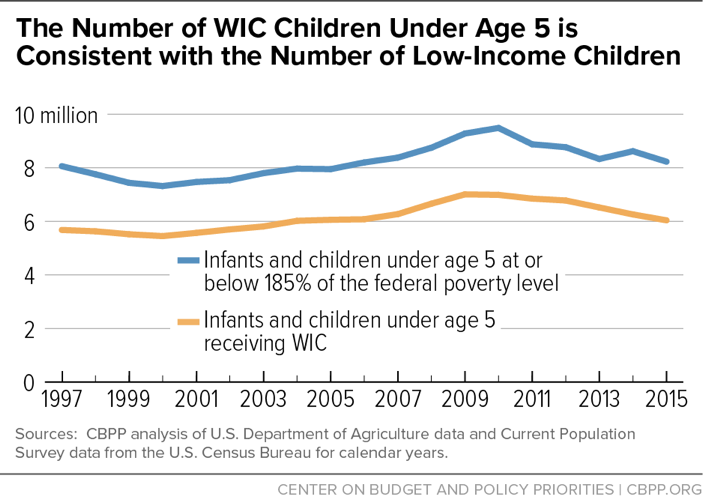

Trends in WIC participation are consistent with trends in the number of low-income women, infants, and young children. With WIC eligibility limited to low-income families, the number of low-income women and young children offers a window into how WIC participation might change. The WIC income eligibility threshold is 185 percent of the federal poverty line (now $37,296 for a family of three). To simplify program administration under what is called “adjunctive eligibility,” an applicant who receives SNAP, Medicaid, or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) cash assistance is automatically considered income-eligible for WIC (without regard to the other program’s income limit). Although roughly 73 percent of people approved for WIC benefits receive one of these other benefits when they apply, the vast majority of WIC applicants reported income at or below 185 percent of poverty in 2014.[10] Trends in the number of women and children who have incomes below 185 percent of poverty are instructive when considering trends in WIC participation.

- The ratio of the number of women participating in WIC to the number of low-income women has been steady. From 1997 to 2015, the number of women participating in WIC rose by 11 percent, a comparable increase to that of the number of low-income women (age 18 to 44 with income at or below 185 percent of poverty), which also rose by 11 percent.[11] Likewise, the percentage of all low-income women who receive WIC was the same in 1997 and in 2015; it stood at just over 10 percent in both years. (The share rose to more than 12 percent during the early years of the recession, but has since declined; see Figure 3.)

- The number of infants and children participating in WIC is consistent with the number of young children living in low-income households. The number of infants and children participating in WIC rose through 2009, and then fell thereafter as the economy strengthened, poverty edged down, and unemployment declined. The number of young children living in low-income families rose through 2010 and then decreased through 2015 (with a slight increase in 2014) while WIC participation continued to fall during this period. (See Figure 4.) WIC also reached a larger share of the eligible low-income infants and children, serving 73 young children for every 100 low-income young children in 2015 compared with 71 in 1997.[12]

The number of infants participating in WIC is consistent with the number of births. WIC aims to ensure that low-income pregnant women obtain the foods they need to deliver healthy babies and that those babies are well-nourished as they grow into toddlers. Both the number of WIC-participating infants and the number of births rose gradually after 1997, with births reaching their recent peak in 2007 and WIC infants reaching their peak about a year later, after which both fell. Births declined by 8 percent between 2007 and 2015 and WIC infant participation decreased by 13 percent between 2008 and 2015.[13] WIC served roughly half of infants born each year, fluctuating between 47 and 54 percent between 1997 and 2015.[14] (See Figure 5.)

Along with the number of participants, two factors determine WIC’s overall cost: the cost of supplemental foods that WIC provides to participants after taking cost containment measures into account, and the cost of its administration and nutrition services (such as nutrition education and breastfeeding promotion). WIC cost containment policies have proven highly effective: WIC food costs have grown significantly more slowly than food prices. In addition, the real per-participant value of funding for nutrition services and administration has remained flat. Notably, WIC spending as a share of the economy has fallen since 1997.

WIC food costs have grown more slowly than grocery store food prices.WIC’s per-participant food costs reflect the grocery store prices for the supplemental foods and the discounted price that WIC pays for infant formula and, to a much lesser degree, for some other WIC foods. After adjusting for food price inflation, the cost of the average WIC food package per participant fell by 23 percent between 1990 and 2016. (See Figure 6.)

WIC has kept average per-participant food costs below inflation largely due to legislation that President George H.W. Bush and Congress enacted on a bipartisan basis in 1989, requiring all state WIC programs to use competitive bidding to buy infant formula.[15] In return for the exclusive right to provide their products to state WIC participants, infant formula manufacturers offer rebates through a competitive bidding process that reduces federal WIC costs by $1.3 billion to $2 billion a year.[16] Along with other cost-containment efforts, this competitive bidding process has proven highly effective, holding increases in the average cost of food for WIC participants to just over half of increases in overall food costs. The actual (nominal) cost of the average WIC food package per participant — including infant formula — rose 41 percent between 1990 and 2016, a period during which food prices overall increased 84 percent.

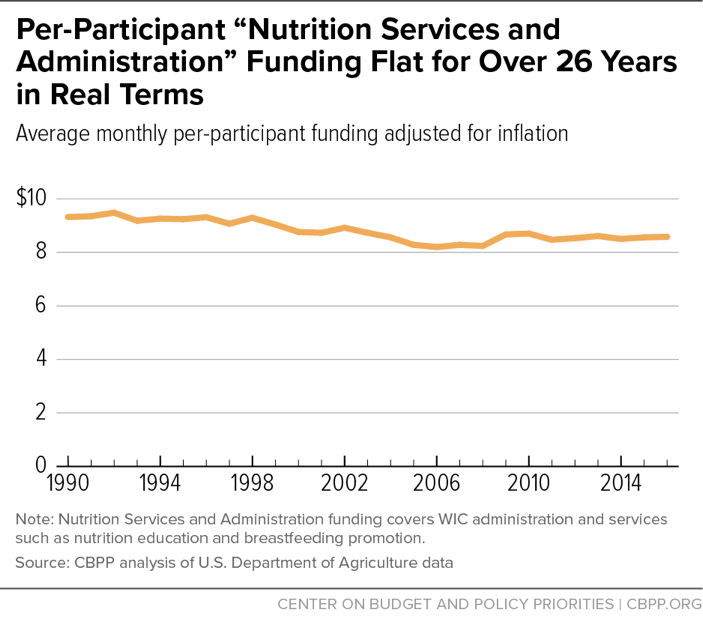

Real per-person funding for nutrition services and administration has remained steady. In 2016, about 8 percent of federal WIC funds were devoted to program administration and about 17 percent to nutrition education, breastfeeding support, and other services, such as smoking cessation support. These costs are covered by “Nutrition Services and Administration” (NSA) funding, which represents roughly a quarter of WIC spending.

WIC’s current funding system for NSA was instituted in 1989 under the same bipartisan legislation that brought competitive bidding for infant formula. Under the law, total federal WIC funds for nutrition services and administrative costs combined, on a per-participant basis, rise only for inflation.[17] Thus, real per-participant funding for these costs has not risen for more than 26 years, even as the nutrition services and administrative tasks that state and local WIC agencies are required to provide have increased. (See Figure 7.)

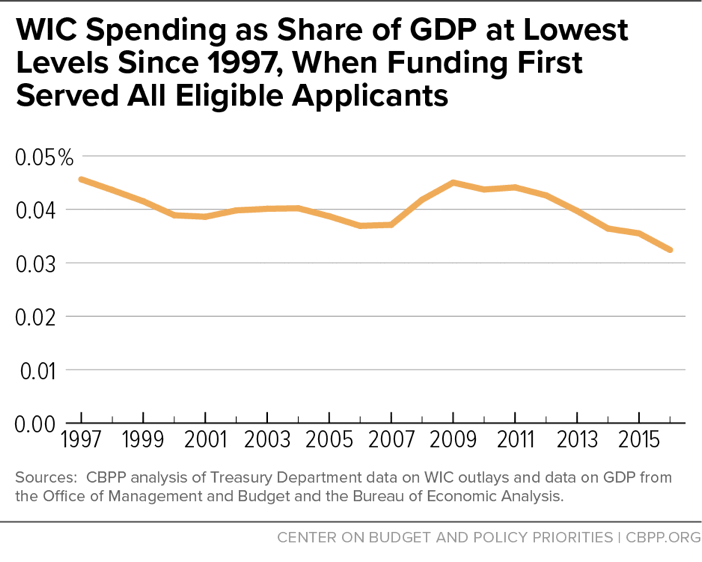

WIC spending relative to the economy has fallen since 1997. Budget analysts often study a program’s spending as a share of the economy, or gross domestic product (GDP), to determine whether program spending, such as for large entitlements like Social Security and Medicare, is sustainable and affordable. In a growing economy and with effective cost controls in place, a program’s spending can decline as a share of GDP, making the program more affordable even if its costs rise in nominal terms.

Due to WIC’s stable participation levels and cost containment efforts, WIC spending relative to the economy has fallen by 29 percent since 1997, rising substantially only during the Great Recession as poverty, unemployment, and need rose before falling back. In 2016, WIC spending as a share of the economy reached its lowest level since before WIC reached full funding in 1997. With WIC spending falling as a share of economy, the program is clearly affordable and is not contributing to the nation’s long-term budget problems. (See Figure 8.)

Despite WIC’s extremely stable caseloads and funding over the past couple of decades, some argue that the program is growing too rapidly and that the link between Medicaid and WIC, known as adjunctive eligibility, is to blame.

Adjunctive eligibility enables WIC applicants to establish their income eligibility by showing proof that they participate in SNAP, TANF, or Medicaid.[18] In 2014, roughly 73 percent of WIC applicants were adjunctively eligible.[19] Congress established adjunctive eligibility in 1989 to simplify WIC’s application process, streamline paperwork, and reduce administrative errors and costs. Adjunctive eligibility continues to be an important simplification for WIC, allowing staff to spend time on nutrition counseling and other services rather than reviewing income documents. In addition to the administrative benefits, the improvements in health and birth outcomes associated with WIC participation can reduce health care costs.

Over the last several decades, some states have extended Medicaid eligibility to pregnant women, infants, and children with incomes above WIC’s 185 percent-of-poverty income limit. These Medicaid changes, which are allowed under state Medicaid options that predate health reform, (see box, “States Have Long Had Flexibility to Raise Medicaid Eligibility for Pregnant Women and Children”) have raised questions about the extent to which adjunctive eligibility results in families at somewhat higher income levels receiving WIC benefits and its impact on overall WIC participation. Some of the most vocal criticism of adjunctive eligibility has come from infant formula manufacturers, which have a vested interest in reducing WIC participation among infants because, as described above, WIC purchases formula at a heavily discounted price obtained through competitive bidding. Mothers of infants who aren’t eligible for WIC pay full price for infant formula, increasing revenues for manufacturers.[20]

Medicaid eligibility expansions make more people eligible for WIC and some argue that they could lead to substantial increases in the number of WIC participants in the future.[21] But these arguments are not supported by data. As discussed below, the data show that higher Medicaid eligibility thresholds have not had a large impact on WIC participation. Moreover, it is highly unlikely that states will continue to increase Medicaid income limits.

The share of WIC applicants with income above 185 percent of poverty is small, USDA data indicate. Only 1.3 percent of WIC applicants reported income above 185 percent of poverty in 2014, according to USDA’s biannual study of WIC participants.[22]

For methodological reasons, that figure could somewhat understate the share. For applicants who are adjunctively eligible, WIC does not need to obtain income information to determine eligibility (although WIC staff do ask applicants to provide income to comply with USDA’s reporting requirements). As a result, the USDA data show, WIC does not obtain income data for about 8.2 percent of applicants. A portion of that 8.2 percent likely has income above 185 percent of poverty (though there is no evidence that the portion of the 8.2 percent that has income above 185 percent of poverty is higher than the share of other WIC applicants who have income above that level).

Individuals eligible at higher income levels are much less likely to participate in Medicaid and WIC than lower-income individuals. Individuals at higher income levels do not participate in Medicaid or WIC at as high a level as lower-income individuals, for two reasons:

- Many people with income above twice the poverty line have other health insurance coverage. At higher income levels, many women and children have private health insurance coverage or government insurance other than Medicaid, and therefore don’t apply for Medicaid even if they are eligible. Based on a CBPP analysis of 2015 Census data, about 78 percent of women age 18 to 44 with income between 200 and 350 percent of the poverty line had other health insurance coverage. By contrast, only about 42 percent of women age 18 to 44 who lived below the poverty line had other coverage. Similarly, about 66 percent of children under age 5 with income between 200 and 350 percent of the poverty line had other health insurance coverage. [23]

- WIC participation rates are likely to be low at higher income levels. Even when families above 185 percent of poverty seek Medicaid coverage, they apparently often don’t seek WIC benefits. That’s consistent with other means-tested programs, in which participation is typically lower for families with higher incomes who are closer to the programs’ eligibility limits.[24] For families that are struggling less, the value of WIC’s food benefit (an average $61.24 monthly per participant in fiscal year 2016) may not be worth the time and effort to apply and show up for subsequent appointments.

MACPAC, the non-partisan agency that provides policy and data analysis to Congress on Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), found that only about 2 percent of children enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP in 2013 had income over 200 percent of poverty even though most states allow children above that income level to qualify for Medicaid or CHIP.[25] This figure is not directly applicable to WIC, as it covers both Medicaid and CHIP (which extends to higher income levels in some states and does not confer adjunctive eligibility to WIC) and it is for children of all ages. But it demonstrates that children from higher-income families have lower participation rates than those from lower-income families.

Most states have not raised their Medicaid eligibility limits. In the decade before the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) major coverage expansions took effect (2003 to 2013), ten states raised their Medicaid limits for pregnant women or infants.[26],[27] In 2016, these states accounted for 12 percent of WIC participants, only 1 percentage point higher than their share in 2003.

Since the implementation of the ACA, four states have expanded Medicaid eligibility for pregnant women, infants, or children under 5. Over the course of 2013, California transferred children who had received health insurance through a separate state CHIP program to Medicaid, thus raising Medicaid’s income limit for children under 5 from 200 percent of poverty to 266 percent. New Hampshire also transferred children age 1 and older from a separate CHIP program to Medicaid. In New Hampshire, infants were already covered up to the higher income level in Medicaid, so the change did not affect adjunctive eligibility for WIC as much as in California. In January 2016, Michigan transferred children who had received health insurance through a separate state CHIP program to Medicaid, thus raising Medicaid’s income limit for infants from 200 percent of poverty to 217 percent and for children ages 1 to 5 from 165 percent of poverty to 217 percent. Similarly, in January 2016 Tennessee increased the Medicaid income limit for infants from 200 percent of poverty to 216 percent and for children ages 1 to 5 from 147 percent of poverty to 216 percent.

Before the ACA’s major coverage expansions took effect in 2014, financial eligibility for Medicaid was determined by taking an individual’s gross income, disregarding amounts that were not considered countable, and applying deductions for child care and work expenses. States compared the result to an income eligibility threshold (referred to as the net income standard) to determine whether the individual was eligible for Medicaid.

The ACA revised the Medicaid rules for counting income, beginning in 2014. Medicaid now uses “Modified Adjusted Gross Income” (MAGI) to align with rules for counting income in the federal income tax code that are used to calculate subsidies to purchase coverage in the new insurance marketplaces. The ACA also required states to eliminate state-specific income disregards and deductions. At the same time, the ACA required states to maintain their Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels for children until 2019.

Eliminating the state-specific disregards and deductions, however, would have resulted in fewer people being eligible for Medicaid under the new methodology. To maintain the same eligibility levels that were in effect before the ACA, the ACA required states to convert their net income standards to equivalent MAGI income standards that take into account the disregards and deductions used by the state. The MAGI-converted thresholds, which states started using in 2014, were designed to result in roughly the same number of people being eligible under the new standard as would have been eligible under the old standard. At an individual level, some people gained eligibility while others lost eligibility, but the converted standard was intended to maintain the same level of eligibility in the aggregate. As a result, Medicaid income limits rose in 2014, but those increases largely reflect the loss of disregards and deductions, not efforts to expand eligibility.

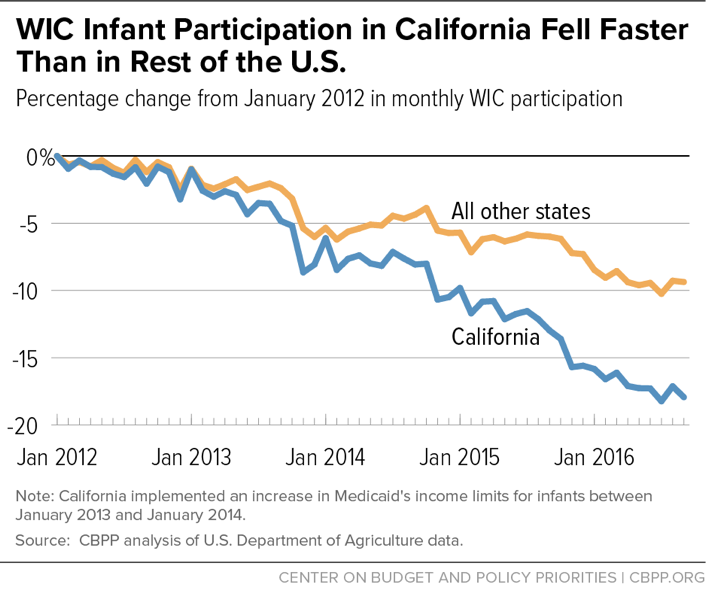

WIC participation is falling in California despite a substantial increase in the state’s Medicaid income limit. California’s experience after substantially raising its Medicaid income limit for children is instructive. The increase made more infants adjunctively eligible for WIC, and it is precisely this kind of change that, according to infant formula manufacturers, results in many more infants enrolling in WIC. To be sure, California made these changes as the economy was recovering from the recession, and WIC participation was declining even before the change took effect. But the decline continued through 2016, and the number of California WIC infants by the end of fiscal year 2016 was 18 percent below the level in January 2012. Even more striking, the number of infants participating in WIC in other states fell by 9 percent over the same period, or only half as much. In other words, despite the substantial increase in the state’s Medicaid income limit for children, WIC infant participation fell more rapidly in California than in other states.[28] (See Figure 9).

The effect of higher Medicaid income limits on WIC participation appears to be small, but the magnitude is difficult to assess because multiple factors are at work.

To be sure, it is difficult to determine precisely the effect that an increase in a state’s Medicaid income limit has on WIC participation in that state or to compare changes in participation across states, because multiple factors can affect state WIC caseloads. For example, the recession hit some states harder than others, and the population grew significantly in some states (especially in the South and West) while growing much more slowly, or declining in others (such as in the North and Midwest). Birth rates, which play a significant role in WIC eligibility, also may vary across states.

In addition, states that accompanied the Medicaid expansion with substantial public education campaigns may have had larger increases in Medicaid enrollment. And, these kinds of campaigns and the ACA’s “individual mandate” also can result in higher participation among lower-income individuals who already were eligible for Medicaid but hadn’t enrolled. (Such increases in participation aren’t due to higher Medicaid eligibility limits, and any such increases are likely to be modest among the WIC population because pregnant women and young children already had quite high Medicaid participation rates before the ACA.) Finally, a state may experience growth in WIC participation if more families with WIC-eligible members apply to participate due to state or health provider outreach efforts, or other factors.

In short, numerous factors independent of adjunctive eligibility affect WIC participation levels across states.

Future Medicaid expansions for infants, children, and pregnant women are unlikely. Coverage for children through Medicaid and CHIP has not been scaled back in part because the ACA requires states to maintain their pre-ACA Medicaid and CHIP coverage levels for children through 2019. This maintenance-of-effort requirement does not apply to pregnant women, however, and a few states have already rolled back Medicaid eligibility for pregnant women. For example, in 2014 Oklahoma scaled back Medicaid eligibility for pregnant women from 185 percent to 138 percent of the poverty line.

Under the ACA, however, the maintenance-of-effort requirement for children’s Medicaid and CHIP coverage will expire in 2019 unless it is extended. While states would still have the flexibility to expand Medicaid to cover young children at higher income levels, increases would be unlikely given recent efforts by Congress and the Administration to reduce federal Medicaid funding. If Medicaid funding is substantially reduced, as proposed under ACA repeal legislation, states would be even less likely to expand coverage.[29]

Before enactment of the ACA, the federal government set Medicaid’s minimum income limits for pregnant women, infants, and young children at 133 percent of the federal poverty line, but states have long had the option to extend coverage to higher levels. Since the 1980s, most states have done so. As of January 2013 — before the ACA’s major coverage expansions took effect — infants in families with incomes above 185 percent of poverty were eligible for Medicaid in about half of states, pregnant women in such families were Medicaid-eligible in 17 states, and children age 1 to 5 in such families were Medicaid-eligible in 15 states, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.a

State income eligibility limits above 185 percent of poverty for Medicaid for pregnant women and children thus aren’t a result of the ACA, which raised the Medicaid eligibility limit (in states adopting the law’s Medicaid expansion) to 133 percent of poverty for all adults and provided tax subsidies to buy coverage in health insurance marketplaces for adults and children with incomes up to 400 percent of the poverty line. Health insurance through the marketplaces does not confer adjunctive eligibility for WIC.

Thus, the ACA did not expand Medicaid eligibility for pregnant women and young children, because they already were eligible for Medicaid in almost every state up to the new ACA expansion limits.

a Kaiser Family Foundation, “Getting into Gear for 2014: Findings from a 50-State Survey of Eligibility, Enrollment, Renewal, and Cost-Sharing Policies in Medicaid and CHIP, 2012-2013,” January 2013.

Since Administrations and Congresses began fully funding WIC, its participation and spending have been stable, rising only modestly during the recession in response to the increased need that resulted from higher unemployment and poverty. With the economic recovery from the recession still ongoing, WIC participation and spending are falling. These declines, combined with the fact that WIC costs per participant have grown more slowly than inflation, have brought WIC spending as a share of the economy down to its lowest level in two decades.