Thank you for the opportunity to testify today. I am Ty Jones Cox, Vice President of Food Assistance Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP), an independent, nonprofit, nonpartisan policy institute located in Washington, D.C. CBPP conducts research and analysis on a range of federal and state policy issues affecting families with low and moderate incomes. The Center’s food assistance work focuses on improving the effectiveness of the major federal nutrition programs, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps). I have worked on SNAP policy and operations for more than 15 years, starting as a legal aid attorney in Virginia where I represented clients in their fair hearing and during their engagement with the Department of Social Services. Much of my current work is providing technical assistance to state officials and advocates, who wish to explore options and policies to improve SNAP operations to more efficiently serve eligible households. My team and I also conduct research and analysis on SNAP at the national and state levels. CBPP receives no government funding for our policy work or operations.

My testimony today explains SNAP’s critical roles in fighting food insecurity and poverty; in supporting health and economic well-being; in defending against hardship during the COVID-19 pandemic; and in supporting people who are paid low wages. I’ll also describe how the recent update to the Thrifty Food Plan, which is used to set the maximum amount of food assistance people participating in the SNAP receive, has increased the adequacy of SNAP benefits, allowing households to better afford a nutritious diet. Finally, I’ll detail opportunities to strengthen SNAP in the next farm bill.

Research shows that SNAP is one of our most effective tools in reducing hunger and food insecurity, which occurs when a lack of resources causes household members to struggle to afford enough food for an active, healthy life during the entire year. As a result, it plays a critical role in our country.

Much of SNAP’s success is due to its structure: it is designed so that everyone who is eligible can get benefits; it expands automatically to meet needs during tough times; and it focuses its benefits to the households with the least resources available to purchase groceries, assisting families with low income to obtain adequate nutrition, regardless of where they live. As of February 2022, SNAP was helping 41 million low-income people in the U.S. to afford a nutritionally adequate diet by providing them with benefits on a debit card that can be used only to purchase food at about 254,000 retailers across the country. On average, SNAP recipients receive about $5.45 per person per day in food benefits, not counting the temporary additional benefits during the current public health emergency. SNAP’s reach shows the extensive need for nutrition assistance and SNAP’s critical role in addressing it.

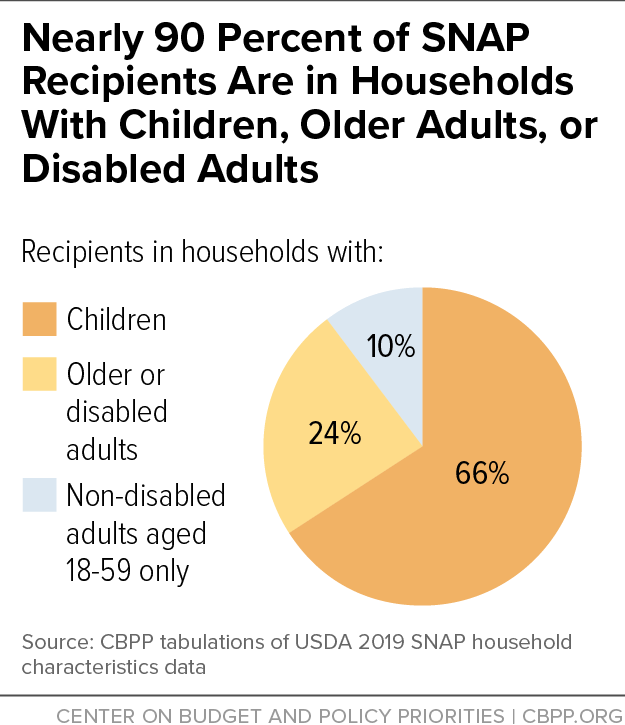

Consistent with its original purpose, SNAP provides a basic nutrition benefit to people with low incomes who cannot afford an adequate diet. SNAP is one of the only federal benefit programs available to almost all households with low incomes; many other programs are limited to certain populations, such as families with children or people with disabilities, or have capped funding that limits the number of people who can receive benefits. Nearly 90 percent of SNAP participants are in households that contain a child under age 18, an older adult 60 years or older, or an individual with a disability. (See Figure 1.) Based on pre-pandemic data, about two-thirds of SNAP participants are in families with children; over one-third are in households with older adults (aged 60 or older) or people with disabilities. Nearly half of SNAP households are headed by a non-Hispanic white person, about a quarter by a non-Hispanic Black person, and more than a fifth by a Latino person (of any race). About 7 percent of SNAP households are headed by a person who is Asian or another race.

Children under age 18 constitute nearly half (43 percent) of all SNAP participants. Participation in SNAP also helps children receive school meals and confers eligibility to the Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). SNAP also benefits many households with workers paid low wages; the share of SNAP households that had earnings in an average month while receiving SNAP has risen over the past few decades, from 20 percent in 1992 to 29 percent in 2019.[1] Many households without earnings in a particular month are temporarily out of work and have worked recently and will work again soon.

SNAP reduces poverty and food insecurity by giving households benefits to buy groceries, which allows them to spend more of their budgets on other basic needs, such as housing, electricity, and medical care. SNAP reaches more than 80 percent of eligible households. It delivers the largest benefits to those least able to afford an adequate diet. About 92 percent of SNAP benefits go to households with incomes at or below the poverty line, and 54 percent go to households at or below half of the poverty line (about $10,980 for a family of three in 2022). Families with the greatest need receive the largest benefits; these households, particularly households with children, also have higher rates of participation in the program.

These features make SNAP a powerful anti-poverty tool. SNAP kept nearly 8 million people above the poverty line in the years before the COVID-19 pandemic, including 3.6 million children.[2] SNAP has one of the strongest anti-poverty effects among government economic security programs and is particularly effective at reducing deep poverty, that is, in lifting families’ incomes above half of the poverty line.

SNAP reduces the overall prevalence of food insecurity by as much as 30 percent, and is even more effective among the most vulnerable, such as children and those with “very low food security,” in which one or more household members skips meals or otherwise eats less during the year due to lack of money. The largest and most rigorous examination of the relationship between SNAP participation and food security found that food insecurity among children fell by roughly one-third after their families received SNAP benefits for six months.[3]

SNAP is highly responsive to the economy. When more households are out of work or see their earnings fall, SNAP automatically expands to serve everyone who is eligible and applies. This mitigates hardship during a recession and gets money into the economy quickly, acting as stimulus for the economy overall. Low-income individuals generally spend all of their income meeting daily needs such as shelter, food, and transportation, so every dollar in SNAP that a household receives, including during a downturn, enables the family to spend an additional dollar on food or other basic needs. Nearly 78 percent of SNAP benefits are redeemed within two weeks of receipt and 96 percent are spent within a month.[4] During the Great Recession and the COVID pandemic, policymakers turned to SNAP as an efficient mechanism for getting additional help to households struggling to afford food and contending with significant income losses and for bolstering aggregate demand, thereby reducing the duration and depth of the economic downturn.

Research backs up how SNAP can act as economic stimulus. Every dollar in new SNAP benefits generates business for local retailers of all types and sizes, and increases the Gross Domestic Product by $1.50 during a weak economy. Similarly, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and Moody’s Analytics found that SNAP has one of the largest “bangs-for-the-buck” for increasing economic activity and employment among a broad range of stimulus policies.[5]

SNAP also acts as a first responder in the wake of the emergencies and natural disasters, providing critical food assistance to vulnerable households. After disasters, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and states work together to provide quick, targeted assistance. This can include replacing participants’ benefits to compensate for lost food, providing temporary Disaster SNAP (D-SNAP) benefits to non-participants who have suffered significant loss, and relaxing program requirements to ease access and relieve undue burden on staff.

SNAP is associated with improved outcomes in health, education, and self-sufficiency. SNAP participants are more likely to report excellent or very good health than low-income non-participants. Research comparing long-term outcomes of individuals in different areas of the country when SNAP expanded nationwide in the 1960s and early 1970s found that access to SNAP during pregnancy and in early childhood improved birth outcomes and long-term health as adults. Studies have linked SNAP to improved educational attainment, higher rates of high school completion, and improved labor market outcomes in adulthood. Older SNAP participants are less likely than similar non-participants to forgo their full prescribed dosage of medicine due to cost. SNAP may also help low-income seniors live independently in their communities and avoid hospitalization.

SNAP is linked with reduced health care costs. On average, after controlling for factors expected to affect spending on medical care, low-income adults participating in SNAP incur about $1,400, or nearly 25 percent, less in medical care costs in a year than low-income non-participants. The difference is even greater for those with hypertension (nearly $2,700 less) and coronary heart disease (over $4,100 less). Two other studies also found an association between SNAP participation and reduced health care costs of as much as $5,000 per person per year. [6]

SNAP enables low-income households to afford more healthy foods. Because SNAP benefits can be spent only on food, they boost families’ food purchases. The updated Thrifty Food Plan (TFP), discussed more below, resulted in higher benefit levels, which will help households better afford a healthy diet featuring more whole grains, different-colored fruits and vegetables, and lean proteins. The fact that SNAP can only be used for food purchased from grocery stores or other food retailers likely encourages better nutrition among participants, because it shifts food spending away from restaurants. In addition, all states operate SNAP nutrition education programs to help participants make healthy food choices.

After the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, SNAP responded quickly to deteriorating economic conditions, pushed back against food insecurity and other forms of hardship, and supported families during periods of unemployment, earnings loss, and uncertainty. Moreover, Congress acted expeditiously to temporarily modify and expand SNAP ― changes that states implemented quickly and effectively ― to deliver additional food assistance to households in communities across the country.

In March 2020, when Congress enacted and President Trump signed the first legislation to address the health and economic impacts of COVID-19, hunger was poised to soar. Calls requesting help with food to state “211” numbers, which households in need of help can use for human services referrals, were over four times greater in late March through mid-May 2020 than earlier in 2020.[7] The food bank network Feeding America distributed 42 percent more food in the second quarter of 2020 than it did in the first quarter, and food banks were growing increasingly concerned about their ability to meet the increased need.[8]

During the Great Recession, the share of households that were food insecure rose from 11.1 percent in 2007 to 14.7 percent in 2009, according to Agriculture Department estimates. Yet during the COVID-19 pandemic, because of SNAP’s structural ability to respond to increased need as well as the robust relief effort in SNAP and other efforts ― including unemployment insurance and economic impact payments ― the typical annual measure of food insecurity in 2020 was unchanged from the 2019 level of 10.5 percent.[9]

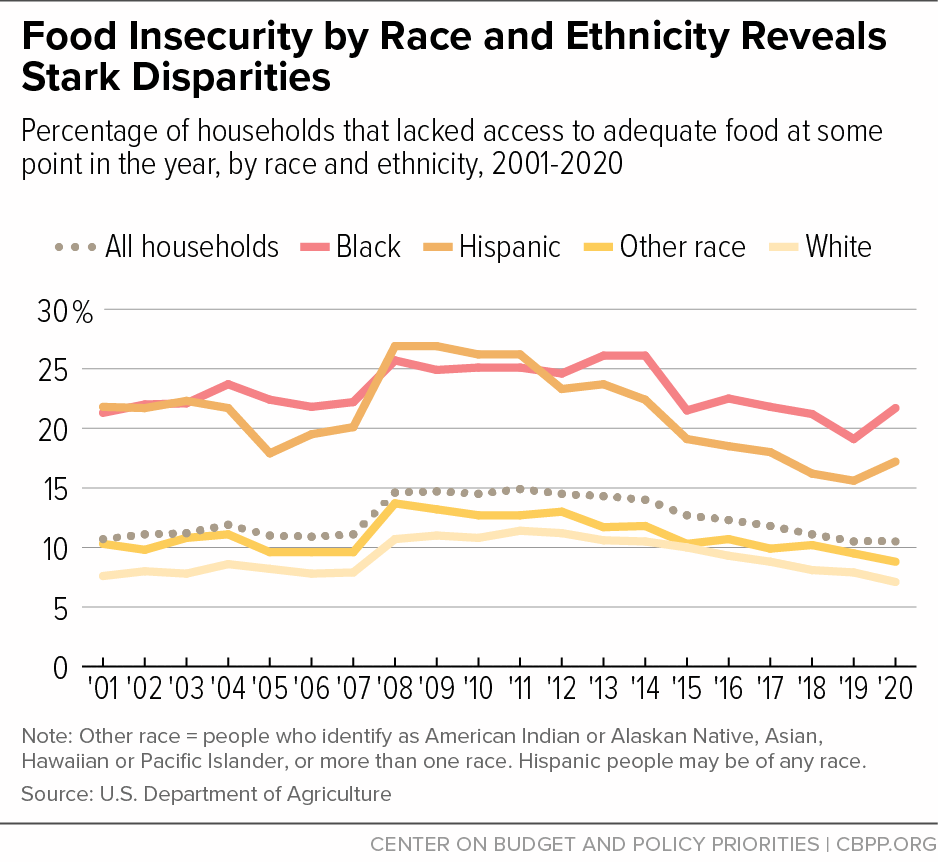

This overall figure obscures that food insecurity under the annual measure did rise for households with children and for households headed by Black adults; people of color have faced higher levels of food insecurity for decades. (See Figure 2.) And other Census data show higher levels of food insufficiency (a different measure of food hardship, in which adults report that their household sometimes or often did not have enough to eat in the last week) during the pandemic than what the annual data show. But it’s clear that SNAP and other forms of economic support prevented food insecurity from surging during the pandemic the way it did during the Great Recession.

Because of SNAP’s structure, participation can expand automatically in response to job and income losses, and policy changes enacted during the pandemic boosted caseloads modestly as well. SNAP is available within a month ― often within a week ― of a household’s application, so it was one of the first forms of economic relief available to many low-income families during the pandemic when people lost jobs, had their hours cut, or were unable to work because of illness.

The number of SNAP participants grew from 37 million in an average month just before the pandemic to 43 million in June 2020. (The total number of individuals helped by SNAP during the pandemic is higher than these point-in-time figures because households enrolled in and left the program over the course of the last two years.) The number of people participating in SNAP has declined since the summer of 2020, but in February 2022 (the most recent data available) more than 41 million people participated, 12 percent above the February 2020 level. CBO forecasts the number of SNAP participants will continue to decline in coming years and ultimately fall below pre-pandemic levels. After a downturn, SNAP caseloads tend to remain elevated for a number of years. One reason is that during a crisis, families who may have already been eligible apply for SNAP as they face greater need and uncertainty. Such households may continue to participate in the program, receiving benefits to augment their low earnings until their earnings rise enough to make them wholly ineligible.

Beginning in March 2020, Congress temporarily modified SNAP rules to further reduce hardship and support the economy, taking advantage of SNAP’s ability to deliver benefits quickly and efficiently on households’ electronic benefit transfer (EBT) cards. These changes included:

- Emergency allotments (EAs). In March 2020 Congress gave states and USDA the flexibility to provide emergency SNAP benefit supplements, which all states did. Congress authorized USDA to approve EAs for as long as the federal government has declared a public health emergency and the state has issued an emergency or disaster declaration. As of May 2022, about 15 states had ended their disaster declarations and were no longer providing EAs. In states providing EAs, all households receive the maximum benefit for their household size; if the difference between the maximum benefit and the household’s original benefit under the SNAP benefit formula is less than $95, then the household’s EA is increased so the total EA benefit is no lower than $95.[10]

- A 15 percent SNAP benefit boost. Congress acted in December 2020 to raise SNAP maximum benefits by 15 percent from January through June 2021. The American Rescue Plan extended the increase through September 2021, when the increase ended.

-

The Pandemic-EBT program (P-EBT). Congress created P-EBT in March 2020 as a temporary program to provide benefits to households with children who miss out on free or reduced-price school meals due to the pandemic. Congress later extended and expanded it to provide benefits to cover certain younger children and during the summer, when food insecurity among children rises.

While not SNAP benefits, P-EBT is delivered on SNAP’s EBT cards and state SNAP agencies played a leadership role in standing up this new program within just a few months. P-EBT reduced the share of families where children experienced very low food security by 17 percent, according to Brookings Institution research. The program reduced food insufficiency, by 28 percent, the same study found. The effects were larger in states that had higher rates of school closures during the pandemic.[11] States’ ability to provide P-EBT benefits is tied to the federal public health emergency. All or nearly all states offered P-EBT benefits during the past couple of school years and last summer. Currently more than half of states have USDA-approved plans to issue P-EBT benefits for the 2021-2022 school year when schools are closed or attendance is disrupted due to COVID-19, and USDA recently issued guidance to states regarding P-EBT for summer 2022.

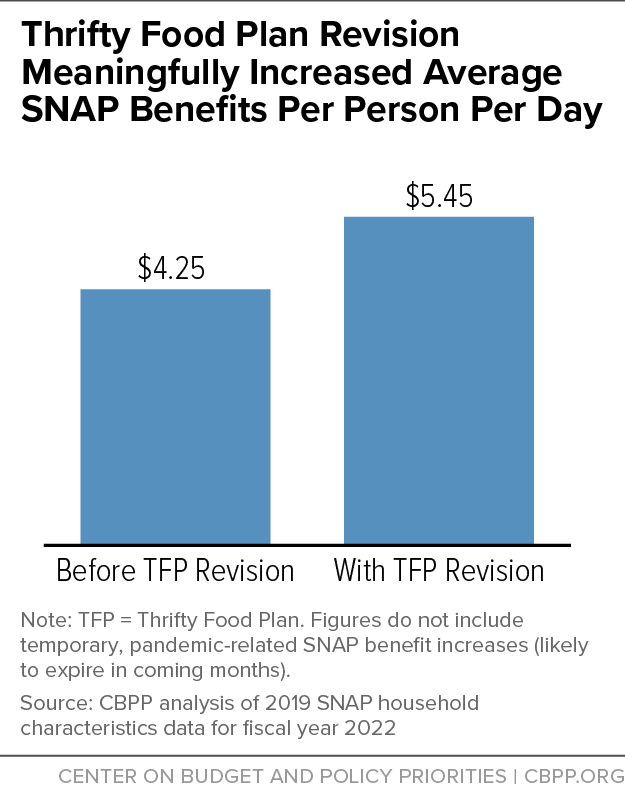

Average SNAP benefits across all households rose from about $120 per person per month before the pandemic to about $230 in the summer of 2021. Since then, SNAP pandemic relief has fallen after the 15 percent benefit boost ended and states have started to pull back on emergency supplements. When the emergency allotments end ― as has happened already in some states and will happen in other states with the end of the federal public health emergency ― SNAP households see their benefits fall by an average of about $80 per person per month, or about 33 percent, though the exact amount depends on the household’s income and other circumstances. The average SNAP benefit per person per day drops from about $8 to about $5.45. Fortunately, because of the update to the Thrifty Food Plan, described below, SNAP benefits after the EAs end are far more adequate than they otherwise would have been.

During the pandemic Congress also:

- Temporarily suspended SNAP’s harsh three-month time limit, which takes benefits away from many adults under age 50 without children in the home when they don’t have a job for more than 20 hours a week;

- Loosened the general rule that makes many college students ineligible for SNAP;

- Allowed waivers of certain administrative process requirements in SNAP to enable administrators to deliver benefits promptly and safely even as caseloads surged and eligibility staff worked from home; and

- Increased funding for the nutrition assistance block grants in Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands and funded additional commodity purchases for emergency food programs.

The pandemic highlighted the critical role that SNAP plays in delivering resources quickly to individuals and their communities. It also reinforced the exceptional dedication and perseverance of the state officials across the country who administer the program with compassion and integrity.

SNAP is an important support for workers who are paid low wages. Millions of people in the U.S. work in jobs with low wages, unpredictable schedules, and no benefits such as paid sick leave — all of which contribute to high turnover and spells of unemployment. SNAP provides monthly benefits that help fill gaps for workers with low and inconsistent pay and can help workers afford food during periods when they are looking for work.

Several features of SNAP’s benefit structure make it an effective support for workers. During the pandemic, SNAP has helped millions of households experiencing unemployment and a turbulent job market. However, SNAP’s harsh three-month time limit for unemployed adults not raising children cuts off benefits for participants who may be looking for work or who face barriers to work, creating hardship with no significant impact on employment among those affected.

SNAP helps workers in low-paying jobs put food on the table. The share of SNAP households that worked in an average month while receiving SNAP grew over the past three decades, until the onset of the pandemic. Work rates rose among all SNAP households, but especially among households with children. This trend continued despite the large job losses in the Great Recession.

Close to two-thirds of working SNAP participants work in service, office and administrative support, sales, or professional occupations. Many of the jobs most common among SNAP participants, such as service or sales jobs like cashiers, cooks, or home health aides, often feature low pay and irregular work hours, and frequently lack benefits such as paid sick leave.[12] These conditions make it difficult for workers to earn sufficient income to provide for their families and may contribute to volatility such as high job turnover. SNAP supplements these workers’ low pay, helps smooth out income fluctuations due to irregular hours, and helps workers when they temporarily lose employment, enabling them to buy food and use their limited resources on other basic necessities.

The pandemic has disproportionately impacted the low-paid labor market and SNAP participants seeking work. The majority of jobs lost in the crisis were in industries that pay low wages, with the lowest-paying industries accounting for 30 percent of all jobs but 59 percent of the jobs lost from February 2020 to October 2021, according to Labor Department employment data. Jobs were down nearly twice as much in low-paying industries (4.5 percent) as in medium-wage industries (2.6 percent) and roughly 15 times as much as in high-wage industries (0.3 percent) during this period.[13] Workers who were born outside the U.S. (including individuals who are now U.S. citizens) experienced larger job losses than U.S.-born workers.

Black and Latino workers experienced a far slower jobs recovery than white workers — reflecting historical patterns rooted in structural racism. By May 2022, however, unemployment rates for Black and Latino workers had returned to pre-pandemic levels, though they still are substantially higher than unemployment rates for white workers. Some 6.2 percent of Black workers and 4.3 percent of Latino workers were unemployed in May 2022, compared to 3.2 percent of white workers.

The majority of SNAP participants who can work do so, either while receiving SNAP or before and after. Many turn to SNAP when they are between jobs. Among SNAP participants who are working-age, non-disabled adults, more than half work while receiving SNAP — and 74 percent work in the year prior to or the year after receiving SNAP. For families with children and at least one working-age, non-disabled adult the work rates are even higher: 75 percent of households with children include someone who works while receiving SNAP and nearly 90 percent of such households include someone who works in the year prior to or the year after receiving SNAP.[14] This shows that joblessness is often temporary for SNAP participants.

The low pay and instability in many low-paid jobs can contribute to income volatility and job turnover: workers paid low wages, including many who participate in SNAP, are more likely than other workers to experience periods when they are out of work or when their monthly earnings drop, at least temporarily. These dynamics lead many adults to participate in SNAP for short periods, often while between jobs or when their work hours are cut. Others, such as workers with steady but low-paying jobs or those unable to work, participate longer term.

People working for low pay are underserved in many states. Even though SNAP provides an important support for these workers, this population is often particularly hard to reach. In 2019, 72 percent of individuals with earnings who were eligible for SNAP participated compared to 82 percent of all eligible people, according to USDA estimates.[15]

SNAP’s design supports work. Some policymakers have raised concerns that programs that provide assistance for low-income families may discourage work if participants are worried that they will face a “cliff” where they lose their benefits entirely if they take a job or increase their earnings above the program’s income limit. SNAP contains three features that result in a fairly small benefit cliff for households with income at the upper end of SNAP’s income eligibility limit.

First, SNAP’s standard benefit formula (in place outside of the current public health emergency) targets benefits based on a household’s income and expenses, but the program phases out benefits slowly with increased earnings and includes a 20 percent deduction for earned income to reflect the cost of work-related expenses and to function as an additional work support. As a result, each additional dollar of earnings results in most households experiencing a decline of only 24 to 36 cents in SNAP benefits. Most SNAP households see an increase in their total income when their earnings rise modestly — particularly if they are in the income range where the Earned Income Tax Credit is increasing as earnings rise — even if some other benefits begin to phase down as well. As a result of the earnings deduction, a household with earnings will receive a larger SNAP benefit than a household of the same size and gross income in which income comes from unearned sources.

SNAP does, however, limit gross income to 130 percent of the federal poverty line, creating a small but meaningful benefit cliff or benefit loss for some households who see their earnings increase from just below to just above that level. This loss of SNAP would cancel out more of the increased earnings than is the case for lower-income households, and, depending on how much the household had increased its earnings, the household may not be better off over a narrow income range.

For example, a single parent with two children working full time at $13.50 an hour would have income at 128 percent of the poverty level and receive about $317 a month from SNAP, making up about 12 percent of their total monthly income. If their hourly wage increased by 50 cents (or $87 a month), lifting the household’s income just above 130 percent of FPL ($2,379 for a family of three per month in fiscal year 2022), the family would become ineligible for SNAP under the federal income eligibility cut-off. In this circumstance, the household’s loss of SNAP benefits would more than cancel out the higher earnings; their total monthly resources would decline by about $230 per month.[16] (The parent may see further wage increases over time, now building from a higher base, and at that point their higher earnings would make the family better off.)

Fortunately, states currently have an option to lift the gross income limit through “broad-based categorical eligibility.” This state option is the second protection in SNAP against a benefit cliff. More than 30 states have taken advantage of the option thereby allowing benefits to phase out gradually for all working households. Consider the previous example in a state that used the categorical eligibility option to adopt a higher gross income limit. The household’s SNAP benefit would drop by only about $30 a month when their income rose, so the household would still be better off with the higher-paying job. The option allows states to smooth SNAP’s phase out and eliminate the relatively modest benefit cliff; states that adopt the option ensure that if a working household is able to increase their earnings, their SNAP benefits phase out slowly and evenly.

The third protection against a benefit cliff is SNAP’s structural guarantee to make food assistance available to every household that qualifies under program rules and applies for help. SNAP households that leave the program because they find a job or get a raise and no longer qualify can count on SNAP being available if they need help again later. Without this guarantee a household that loses its job might have to wait until funding became available to resume benefits — as occurs now with child care and other benefits that are constrained by funding limitations from serving all who are eligible. That SNAP can serve all who qualify for its benefits lowers the perceived risks of working, making it easier for low-income families to take a chance on a new job or promotion.

SNAP’s time limit does not increase work effort but does cut people off benefits. SNAP’s role as the nation’s primary anti-hunger safety net has long had a gaping hole. Non-elderly adults without children in their homes can receive benefits for only three months every three years, unless they are working at least 20 hours a week or can document they are unable to work. Most states offer little if any help in meeting the 20-hour requirement, so the rule is actually a time limit on benefit receipt, cutting off all individuals who are unable to find enough hours of work. States can temporarily waive the time limit in areas where there are insufficient jobs. Due to the pandemic, the time limit is temporarily suspended nationwide.

Research shows that taking food away from households does not lead to increased work effort or earnings. A recent USDA report adds to the growing evidence that the time limit doesn’t lead to SNAP participants finding a job.[17] By taking SNAP away, the time limit leaves people with fewer resources to buy food and puts them at risk of food insecurity.

Additional research supports these findings. A recent paper showed that SNAP’s time limit reduced participation in the program by 53 percent among those subject to the time limit, again with no effects on employment.[18] Earlier research found people subject to the time limit lost SNAP benefits and that losing SNAP eligibility did not increase employment but did increase the number of days people reported being in poor health.[19]

Studies also confirm that individuals potentially subject to the time limit are more likely to have significant barriers to employment, such as lack of a high school diploma or GED, a felony conviction, or lack of transportation or a driver’s license, and have higher rates of homelessness and mental or physical conditions that can impact their ability to work.

SNAP’s purpose is to help participants afford a variety of healthy foods. SNAP benefit levels are tied to the cost of the Department of Agriculture’s Thrifty Food Plan, a food plan intended to provide adequate nutrition at a budget-conscious cost.

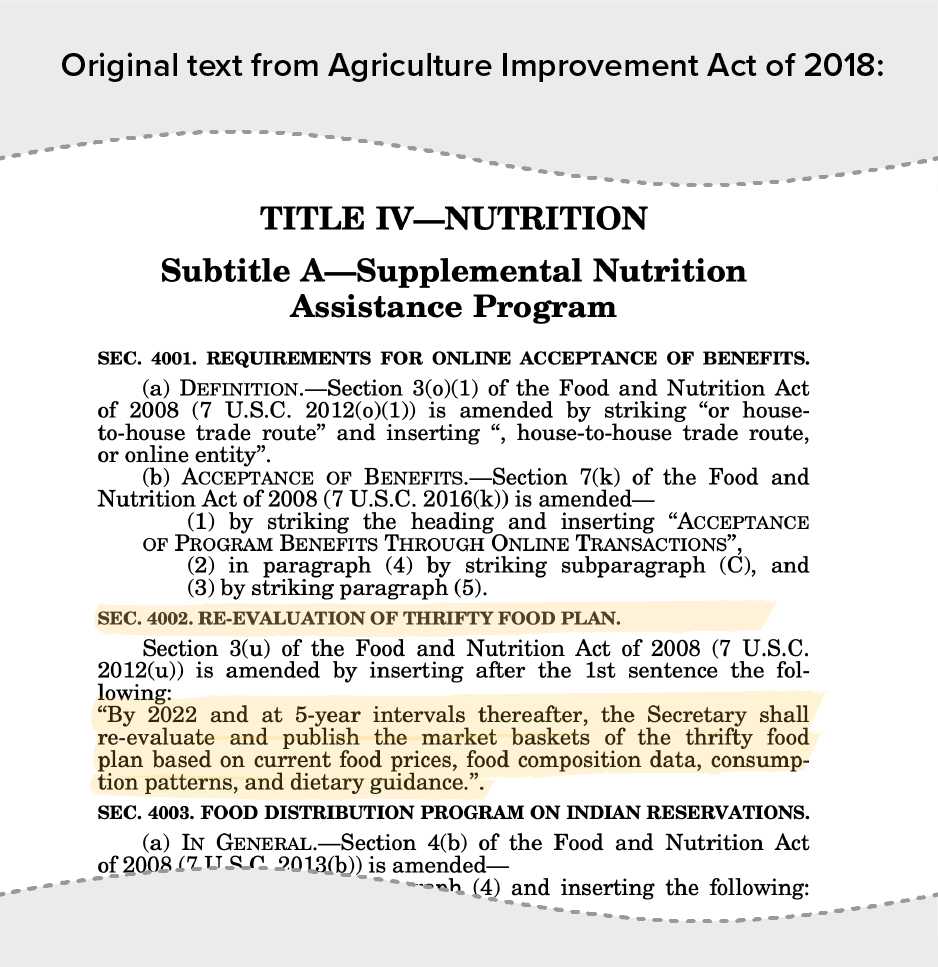

The bipartisan 2018 farm bill directed USDA to reevaluate the Thrifty Food Plan to better reflect the modern cost of a healthy diet by 2022 and every five years thereafter. (See Figure 3.) USDA’s updated Thrifty Food Plan, which was issued in August 2021 (meeting the statutory timeframe) and went into effect at the start of fiscal year 2022, increased SNAP’s purchasing power, raising average benefits per person per day by about $1.20 to about $5.45 in fiscal year 2022, which will help millions of families’ ability to add a greater variety of fruits, vegetables, and other healthy foods to their diet.[20]

It had been 15 years since USDA last revised the TFP and nearly 60 years since it reexamined the TFP’s real purchasing power. The revised TFP is a model food plan that’s more: in sync with what families with low incomes eat, or would eat if less budget constrained; attuned to the realities of time-strapped families; and reflective of scientific evidence for a nutritious, varied diet that includes more whole grains, different-colored fruits and vegetables, and lean proteins (including seafood).

SNAP expects families receiving benefits to spend 30 percent of their net income on food. Families with no net income receive the maximum benefit, which is set at the cost of the Thrifty Food Plan. For all other households, the monthly SNAP benefit equals the maximum benefit for that household size minus the household’s expected contribution.

Before USDA’s revision, the Thrifty Food Plan had been adjusted only for inflation since the 1970s, even as our understanding of what constitutes a healthy diet changed. That left SNAP benefits badly out of line with the most recent dietary recommendations and the economic realities most struggling households face when trying to buy and prepare healthy foods.

Prior to the TFP revision, many families struggled once SNAP benefits ran out. About one-quarter of all households exhausted virtually all their benefits within a week of receipt, and more than half exhausted virtually all benefits within the first two weeks. Numerous studies have found that late in the benefit cycle (that is, toward the end of the month), SNAP participants consumed fewer calories (with the probability of going an entire day without eating tripling from the first to the last day of the month), were likelier to experience food insecurity, visited food pantries more frequently, and may have been more likely to visit emergency rooms or to be admitted to a hospital because of low blood sugar. In addition, at the end of the benefit month, children’s test scores were lower and they were more likely to misbehave in school.[21]

Scientific evidence now emphasizes the importance of eating a broad range of somewhat more costly foods, including more whole grains, red, orange, and leafy green vegetables, lean proteins, and seafood. To prepare a healthy diet, families must have enough money to buy ingredients, as well as the time needed to plan meals, buy and prepare food, consume meals, and clean up. With the increase in women’s labor force participation since the 1970s, and with many parents working multiple jobs, many families lack this time for food preparation.

To stay cost-neutral over the years, the TFP had relied on a limited set of less-expensive foods, had assumed that families can spend a considerable amount of time preparing meals mostly from scratch, and had not accounted for varying family types and dietary needs. As a result, SNAP benefits had fallen short of what many people need to buy and prepare healthy food.

The update to the TFP resulted in a meaningful but modest SNAP benefit increase. The 21 percent increase in maximum SNAP benefits raised the average benefit from about $4.25 per person per day (without the temporary, pandemic-related increases that are now in place but expire in the coming months) to about $5.45 per person per day in fiscal year 2022. (See Figure 4.)

About 2.4 million people, including more than 1 million children, will be lifted above the poverty line because of this modest increase, based on a CBPP estimate that uses the Supplemental Poverty Measure and Census data for 2017.[22] The TFP adjustment is projected to cut the number of children participating in SNAP whose families have annual incomes below the poverty line by 15 percent and will reduce the number of children in poverty overall by 12 percent, we estimate. In addition, the TFP adjustment will reduce the severity of poverty for another 20.5 million people, including 6.2 million children.

Of the roughly 23 million people the change will lift above or closer to the poverty line, 9.4 million are white, 6.5 million are Latino, 5.3 million are Black, and 900,000 are Asian.[23]

More adequate SNAP benefits can help reduce food insecurity, research shows. Those improvements can have long-term impacts, such as supporting economic mobility and reducing health care costs. Children participating in SNAP face lower risks of nutritional deficiencies and poor health, which can improve their health over their lifetimes. SNAP also can affect children’s ability to succeed in school. One study, for example, found that test scores among students in SNAP households are highest for those receiving benefits two to three weeks before the test, suggesting that SNAP can help students learn and prepare for tests — and that when benefits run out and families are struggling to afford groceries, children’s ability to learn is diminished.[24]

Improving the adequacy of SNAP benefits is particularly important in addressing disproportionately high rates of food insecurity among Black and Latino households. Poverty and food insecurity rates are higher among Black and Latino households due to racism and structural factors, including unequal education, job, and housing opportunities, that contribute to income disparities.

These higher benefit levels will help households better afford a healthy diet featuring enough different fruit and vegetables, a recent USDA study simulating the impact of the benefit increase found.[25] And with fewer cost constraints on their food budgets, participating households can better meet dietary guidelines for fruit and vegetable consumption while leaving more of their benefits to purchase other types of nutritious foods.

In research we helped support, economists Michele Ver Ploeg and Chen Zhen found that increasing SNAP benefits is expected to increase spending on groceries, improve the dietary quality of food purchases, and increase the amount of key nutrients, such as iron and calcium.[26] In another study, economics professors Patricia Anderson and Kristin Butcher found that boosting SNAP benefits would raise not only the amount that low-income households spend on groceries but also the nutritional quality of the food purchased.[27]

Anderson and Butcher estimated the impact of an increase in SNAP benefits of $30 per person per month — slightly less than the $36 per-person, per-month increase due to the TFP update. The researchers found that a $30 monthly increase would result in about $19 per person per month more in food spending. (This is less than the SNAP benefit increase because the added benefits free up household income for other necessities such as rent, utility bills, or non-food items that SNAP doesn’t cover.) That increase in food spending, in turn, would raise consumption of more nutritious foods, notably, vegetables and certain healthy sources of protein (such as poultry and fish), and less fast food. The increased food spending would also reduce food insecurity among SNAP recipients.

There is strong evidence that SNAP is working well, but there are certainly parts of the program that should be improved. The coming farm bill is a time to address areas of the program that could be more effective. It is still early in the farm bill process, and this list is not comprehensive, but rather is meant to suggest possible areas for the Committee to consider.

USDA estimates in recent years, prior to the pandemic, that SNAP reached more than 80 percent of people who qualified for benefits. But some people face barriers to gaining access and either participate at lower rates or may not be eligible. A major area for consideration is how to strengthen SNAP to address the risk of food insecurity for these populations, many of whom are disproportionately people of color.

Bring parity to food assistance in Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Despite higher levels of poverty than the rest of the U.S., these three territories are excluded from SNAP (unlike Guam and the Virgin Islands) and instead receive block grants for nutrition assistance. Because of the block grants’ low, capped levels, these territories have more limited eligibility and/or benefit levels and the programs are not able to respond to changes in need because of economic downturns or disasters.

For example, Puerto Rico’s household food assistance program, the Nutrition Assistance Program (NAP, or PAN for its name in Spanish, Programa de Asistencia Nutricional) is one of the most important programs helping people meet basic needs in Puerto Rico. On average about 1.3 million people participated in NAP in 2018, about two-fifths of the territory’s population. But because it is a capped block grant, NAP’s support is more limited than SNAP. Puerto Rico sets eligibility and benefit levels to keep the program’s cost within the fixed federal funding limits, which means these levels aren’t solely based on, and can’t fully respond to, need.

As a result, under regular NAP rules (not including the recent temporary disaster benefits), a parent of two children who lost a job and had no other income received an average of $376 in monthly NAP benefits in March through June 2019.[28] By comparison, a parent of two children who lost a job and had no other income would have received the maximum monthly SNAP benefit of about $505 in the continental United States in 2019, and more in Alaska, Hawai’i, Guam, and the Virgin Islands. SNAP’s funding structure also enables it to respond to changes in demand, including those due to natural disasters or recessions, which NAP, with its limited funding, can’t.

Congress recently funded USDA to conduct research to help determine the information and changes that would be needed to transition Puerto Rico to SNAP, including administrative changes and the development of a methodology to determine SNAP benefit levels based on food price data and consumption data for Puerto Rico. The data used to estimate the Thrifty Food Plan for SNAP is not available for Puerto Rico, but available data on food prices suggests that they are higher in Puerto Rico than in other parts of the U.S.

Similarly, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) receives insufficient funding for food assistance despite high levels of poverty. A 2016 USDA-funded study of the feasibility of including the CNMI in SNAP reported that more than half of the CNMI’s population had income below the federal poverty level, and median household income in the CNMI was less than half the median income in Guam, its nearest neighbor, and in the United States as a whole.[29] Like Puerto Rico, the CNMI has had to set eligibility and benefit levels far lower than in the states, the District of Columbia, and Guam and the Virgin Islands. Under a new memorandum of understanding, the CNMI’s benefit amounts have increased, eligibility was expanded, and a contingency reserve fund was created to be available to meet unanticipated needs. But additional changes are needed to allow food assistance in the CNMI to reach full parity with SNAP.

USDA and Congress have made some progress in recent years in taking steps to address the needs in the territories, document the challenges, and assess the feasibility of changes that would be needed to bring parity to the food assistance provided to these territories’ residents, but more needs to be done, in consultation with the territories, to achieve parity in food assistance.

End SNAP’s three-month time limit, which excludes many unemployed or underemployed workers. As described above, one of SNAP’s harshest rules limits unemployed individuals aged 18 to 50 not living with children to three months of benefits in any 36-month period when they aren’t employed or in a work or training program for at least 20 hours a week. This rule is a time limit on benefits and not a work requirement, as it is sometimes described, because states are not required to provide any way for an individual to meet the requirement — and most do not. Thus, an individual looking for work, or working fewer than 20 hours, will lose food assistance after three months.

Those subject to this rule have extremely low incomes and often face barriers to work such as a criminal justice history, racial discrimination, or health impairments. They also tend to have less education, which is associated with higher unemployment rates. In addition to being a harsh policy that takes critical food assistance away from people who need it without any significant positive impact on employment, the rule is one of the most administratively complex and error-prone aspects of SNAP law. Many states also believe the rule undermines their efforts to design meaningful work activities for adult SNAP recipients as the time limit imposes unrealistic dictates on the types of job training that will permit someone to continue to receive basic food assistance so they can eat. For these reasons, many states and anti-hunger advocates have long sought the rule’s repeal or moderation.

Congress suspended the time limit during the COVID-19 public health emergency in recognition of the pandemic’s effects on the labor market. Rep. Adams through H.R. 4077, the Closing the Meal Gap Act of 2021, and Rep. Lee, through H.R. 1753, the Improving Access to Nutrition Act of 2021, (both with numerous co-sponsors) would end the time limit, restoring eligibility for many individuals who will have food assistance taken away once the public health emergency ends, regardless of their own circumstances, due to a misguided policy that has been shown to increase food insecurity while having no positive impact on employment.

Raise participation rates among eligible older adults. Many older adults have limited income from Social Security and or Supplemental Security Income and could benefit from SNAP benefits, which before the pandemic averaged about $120 a month for households with members 60 years or older. But only about half (48 percent in 2019) of eligible adults aged 60 and over participate in SNAP, though participation rates have risen modestly in recent years.[30] Moreover, most who would qualify for SNAP also would qualify for Medicare Savings Programs, which defray Medicare premiums and/or cost-sharing charges for seniors near or below the poverty line who are not enrolled in the full Medicaid program, and for the Low-Income Subsidy for the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit. But participation rates in these programs among low-income seniors also are very low. While these programs have similar eligibility rules, the differences can be confusing and older adults typically must apply for them via different duplicative processes and may not be aware of the assistance that is available.[31] Tackling low participation rates across programs would address food insecurity as well as help low-income seniors make ends meet overall.

Lower barriers to SNAP participation among certain immigrants and college students experiencing food insecurity. SNAP eligibility rules for immigrants and college students are very complicated. Many individuals in these groups who have low income and for whom assistance with affording food could ease hardship and help them improve their future health and economic well-being are not eligible for SNAP benefits. Others who do qualify are not aware they are eligible; are reluctant to participate out of concern about possible ramifications for their immigration status, even though those concerns are generally not accurate; or face barriers navigating SNAP’s sometimes complicated and burdensome application procedures.

Participation by eligible people who are immigrants and children in families that include immigrant adults has decreased substantially in recent years, according to USDA estimates, likely due in large part to the Trump Administration’s efforts to discourage immigration and to change the public charge rules to include SNAP and other health and economic support programs. Between 2016 and 2019, the participation rate for eligible people who are immigrants dropped from 66 percent to 55 percent and for children who are U.S. citizens who live with adults who are immigrants from 80 percent to 64 percent.[32]

We recommend Congress consider how to improve access to SNAP for low-income immigrants and college students and other groups who cannot qualify or who have low participation rates because of confusion or because they face enrollment barriers.

Allow formerly incarcerated individuals with drug felony convictions to participate in SNAP. Denying food assistance to people who have completed their sentences makes it harder for them to get back on their feet and may contribute to high rearrest rates, which are up to 50 percent for people with prior drug offenses.[33] Given that formerly incarcerated people also face barriers and discrimination in employment and housing, it’s not surprising that 91 percent are food insecure.[34] While most states have restored eligibility to some individuals affected by the ban, these limited restorations leave too many individuals who have completed their sentences and are complying with parole or probation ineligible for SNAP. SNAP’s drug felon ban also disproportionately affects people of color, reflecting — and amplifying — the stark racial disparities in the criminal justice system, with impacts extending to these individuals’ children and other family members.[35]

Support tribal sovereignty and strengthen food security in Native communities. American Indians and Alaska Natives experience food insecurity at a much higher rate than white people. The 2018 farm bill included administrative improvements to the Food Distribution on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) program, which provides food packages to Native American families who live in designated areas near reservations and in Oklahoma as an alternative to SNAP. The bill also authorized demonstration projects through which Indian Tribal Organizations, instead of USDA, can directly purchase commodities for their FDPIR food packages. Congress should work with tribal stakeholders to build on this progress and strengthen food security in Native communities.

SNAP’s current performance measurement system emphasizes preventing improper payments. States and USDA take their roles as stewards of public funds seriously and have a rigorous measurement system in place to assess the accuracy of eligibility and benefit determinations. States are assessed fiscal penalties if their payment error rates are persistently too high.

When a household applies for SNAP it must report its income and other relevant information; a state eligibility worker interviews a household member and verifies the accuracy of information using third-party data matches, paper documentation from the household, and/or by contacting a knowledgeable party, such as an employer or landlord. When errors do occur they are overwhelmingly from unintentional mistakes by applicants or recipients, eligibility workers, or other state agency staff, rather than fraud.

It is critical that SNAP have a strong system in place to assess and address program integrity. But it is also important that the measures states and USDA take do not undermine the program’s purpose to deliver food assistance to households that face difficulties affording an adequate, healthy diet.

Currently information is not available to policymakers or the public about how well SNAP is working in terms of the human experience of accessing benefits. The 2018 farm bill eliminated SNAP performance bonuses, which were tied to low or improving payment error rates, participation rates among eligible people, and delivering benefits promptly within federal timelines. But states still are subject to fiscal penalties for high payment error rates, which places a disproportionate emphasis on payment accuracy over access for low-income families.

In collaboration with the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Code for America developed a National Safety Net Scorecard to put forward a package of metrics that federal and state governments could use to track program performance over time and across states or other jurisdictions.

The measures in the National Safety Net Scorecard measure performance across three categories:

- Equitable access: These metrics help assess whether the programs are open to all eligible people. Are online, telephone, and in-person services available and accessible to all people? How difficult is it to apply? Are people who apply satisfied with their experience?

- Effective delivery: Measures in this category examine the smoothness of the process after a person applies. How long does it take to receive benefits? How common is it for cases to be denied for procedural reasons as opposed to reasons related to financial eligibility? Are people who remain eligible able to successfully maintain eligibility?

- Compassionate integrity: Finally, this category assesses whether people are receiving the benefits to which they are entitled. What share of eligible people participate? How accurate are eligibility and benefit determinations? How smooth is the appeals process?

Some states measure some of these types of metrics as part of their operations or to make the case to the public that they are running successful programs. But there is a need for leadership to make progress toward this vision through federal legislation in the farm bill, administrative action, and further state innovation.

Ensure SNAP Program Operations and Oversight Keep Pace With Technology

The farm bill presents an important opportunity to reassess program operations and ensure SNAP keeps pace with technological and other changes. The pandemic has presented challenges and opportunities that resulted in the program adapting quickly out of necessity. Some technological changes, such as online shopping and remote eligibility practices, that probably would have occurred over time did so instead on an accelerated timeframe. Below are some areas Congress should consider to support these advancements.

- Online purchases. Probably the best example of an accelerated timeframe around technology is the rapid expansion of online purchases during the pandemic. Though less than 10 percent of SNAP benefits are redeemed online, USDA rapidly expanded the number of states and the number of stores that allow recipients to redeem their benefits online. The provisions from the last two farm bills that piloted and studied online benefits were a big reason that USDA, states, and retailers were able to expand so quickly during the pandemic. This next farm bill presents an opportunity to continue the progress from recent years and improve access to online benefits for participants.

- EBT. The original roll-out of EBT revolutionized SNAP benefit delivery, beginning more than 30 years ago. The committee should consider, in collaboration with USDA and other stakeholders, whether to incorporate advancements in retail transactions, such as mobile payment options, while protecting program integrity and ease of use for participants.

- The National Accuracy Clearinghouse (NAC). The 2018 farm bill provided that USDA and states should expand to nationwide a pilot program that several states use to share data on their SNAP participants and prevent individuals from participating in more than one state. An evaluation of the NAC found that less than 0.2 percent of SNAP participants were participating in multiple states. In addition to improving program integrity, the NAC holds promise as a customer service improvement for applicants because it can help participants who move from one state to another disenroll more quickly from benefits in their former home state so that their new home state can open their SNAP case. Congress should monitor the roll out of the NAC nationwide, which is underway and expected to accelerate later this year, to ensure that it does not pose challenges to privacy or vulnerable individuals’ access to benefits.

-

Ensuring accessibility of certification and recertification. Gradually over recent decades, SNAP and other income support and health programs have transformed from very labor intensive in-person application and recertification processes to making far greater use of online, telephone, and other technological tools. States adapted and expanded these tools very quickly during the pandemic when they needed to move to remote operations. These tools, combined with the temporary flexibilities that Congress and USDA allowed during the pandemic, helped states manage their workloads and helped participants gain and maintain access to the program.

Congress should consider revisions to SNAP rules that would support the use of technology in the SNAP certification process. For example, telephonic signatures and text messaging have shown promise in improving access for some households. Making use of available electronic data sources, when relevant, timely, and accurate can lower documentation burdens on households and state agencies. However, technology does not work for all SNAP households. For example, some households do not have telephones or internet access. Some households, including some with elderly or disabled members and those experiencing homelessness, may prefer an in-person process rather than navigating online and telephone communications. It is important that the program balance the use of promising technology with ensuring that states’ certification processes are accessible to everyone.

The recertification process is another area the Committee could focus on where technology could be used to improve customer service. Most households need to reapply for SNAP every year (or for every two years for households with elderly or disabled members) and are required to submit periodic reports about changes in income and some other circumstances halfway through that period. But the recertification and reporting processes present hurdles for many households that result in eligible households losing out on benefits because of mail issues, difficulty scheduling telephone issues, a verification problem, or other procedural issues. Funding to support states making more use of certain technological advancements such as text messaging, reliable third-party data sources, or information from other programs could help keep eligible households connected to SNAP and save state agencies from needing to spend more time processing re-applications from households that lose benefits for procedural reasons.

-

Using data for outreach and enrollment. Many individuals and families who have low incomes qualify for a package of benefit programs, but they often need to apply separately and provide paperwork multiple times to apply for and maintain different benefits. In some cases, a program can use data (such as income) that another trusted program has collected and verified to reduce burdens on state and local administrators and enable applicants to avoid having to provide the same paperwork to multiple offices. For example, all participants in SNAP, Medicaid, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families monthly cash assistance are “adjunctively eligible” for WIC, which means the WIC program does not need to redetermine financial eligibility, but the family still must contact the WIC agency to apply.[36]

In other cases states can use information provided to one program to trigger an application for another program, using a check box, for example, or for targeted outreach. These kinds of linkages hold substantial promise to improve efficiency and program participation but can be tricky for states and the federal government because of different administrative and jurisdictional structures. But leadership from Congress in creating the legal authorities and the expectation of cross-program enrollment, collecting and sharing data and best practices, and offering funding to support these efforts could help elevate the issue and smooth the way.

SNAP is a highly effective program that alleviates hunger and poverty, has positive impacts on the long-term outcomes of those who receive its benefits, and supports people in low-paid jobs and those between jobs. While there are ways in which SNAP could be improved, I urge you to protect SNAP so that it can continue to play its critical role in supporting food security and to make changes that will strengthen its effectiveness, particularly among racial and ethnic groups with high rates of food insecurity due to historical structural inequities.