The 2016 budget resolution, which Congress adopted on May 5 with only Republican votes, represents an alarming vision for the nation’s fiscal future. It proposes to slash non-defense programs by nearly $5 trillion over the next decade, shrinking much of government to levels not seen in the modern era. It concentrates nearly two-thirds of these cuts on programs that serve people of limited means. If implemented, the plan would cause tens of millions of people to lose their health insurance or become underinsured, reduce basic food assistance for large numbers of low-income families and individuals, shrink support for millions of working families struggling to make ends meet, and make it harder for low- and modest-income students to afford college.

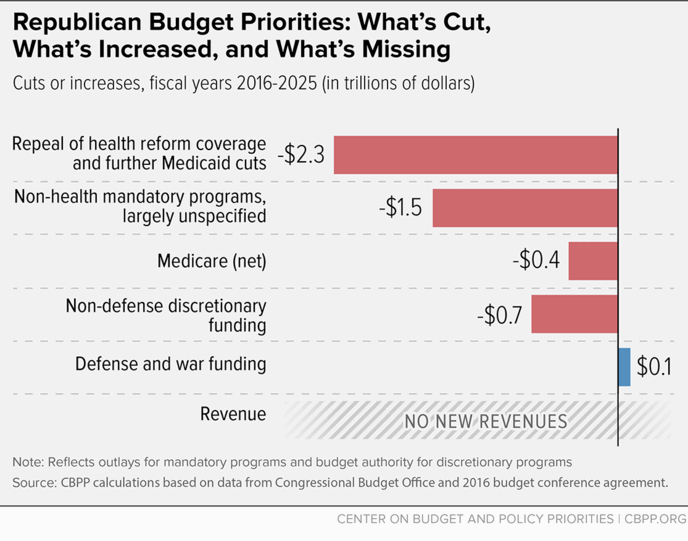

The plan’s distorted priorities reflect its focus on balancing the budget over the decade without any new revenue (even from scaling back tax breaks for the wealthy) and while slightly increasing defense funding. Enshrining budget balance as the preeminent policy goal is neither necessary nor appropriate.

Fortunately, most of the budget’s policy proposals will not readily become law. A congressional budget resolution by itself does not change any funding levels or any statutory language affecting expenditures and revenues. Rather, a budget resolution is a blueprint, and its proposed policy changes can be implemented only if Congress adopts and the President signs subsequent legislation embodying those changes.

This report begins with an examination of the $4.9 trillion in non-defense spending cuts in the budget plan. Next it explains the gimmick the plan uses to provide additional funding for defense in 2016. It then discusses the revenue proposals — or the lack thereof — in the budget. The report then addresses the key budget process changes in the plan. The final section describes the pivotal budget decision points later this year, which are expected to occur on two tracks. One is an expedited legislative process known as “reconciliation” that the Republican majority is expected to use to attempt to repeal or modify the Affordable Care Act. The second involves negotiations around the funding levels for appropriated programs.

The budget plan proposes to cut $4.9 trillion from non-defense programs through 2025. (See Table 1.) These cuts are in addition to those already dictated by the 2011 Budget Control Act’s (BCA) budget caps and by sequestration, described in more detail below.[1]

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| Program Cuts: |

Total |

Programs for People with Low or Modest Incomes |

|---|

| Health care programs |

-2.7 |

-2.2 |

| All other mandatory programs |

-1.5 |

-0.7 |

| Subtotal, mandatory cuts |

-4.2 |

-3.0 |

| Non-defense discretionary |

-0.7 |

-0.1 |

| Total non-defense program cuts |

-4.9 |

-3.1 |

| Increased defense and war spending |

+0.1 |

|

| Resulting interest savings |

-0.8 |

|

| Grand Total, net reduced spending |

-5.6 |

|

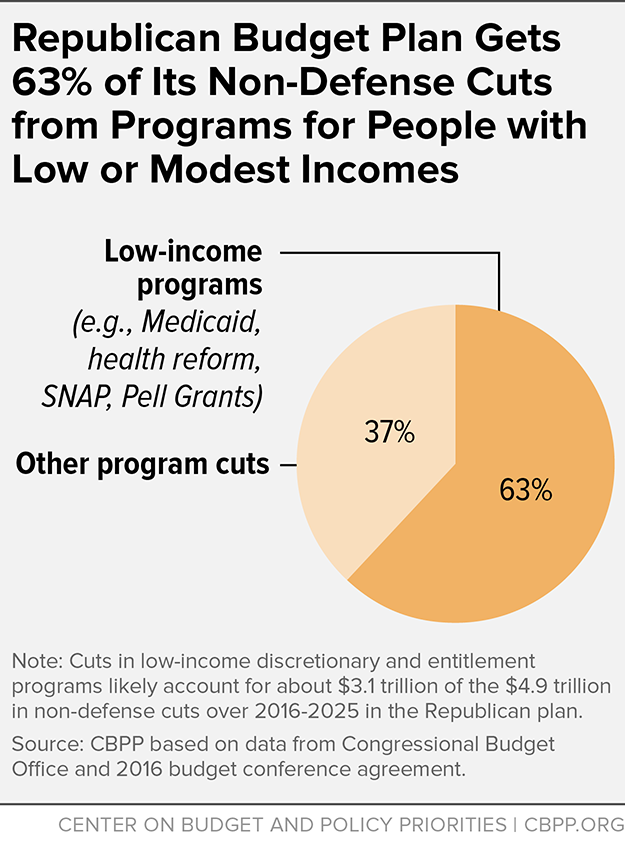

Cuts in programs that assist families with low and moderate incomes — whether to entitlement (“mandatory”) spending programs or to annually appropriated (“discretionary”) programs — account for about $3.1 trillion of the $4.9 trillion in non-defense cuts, and probably more.[2] The budget plan disproportionately targets these programs for 63 percent of the cuts even though they constitute only about one-fourth of program spending.[3] (See Figure 2.)

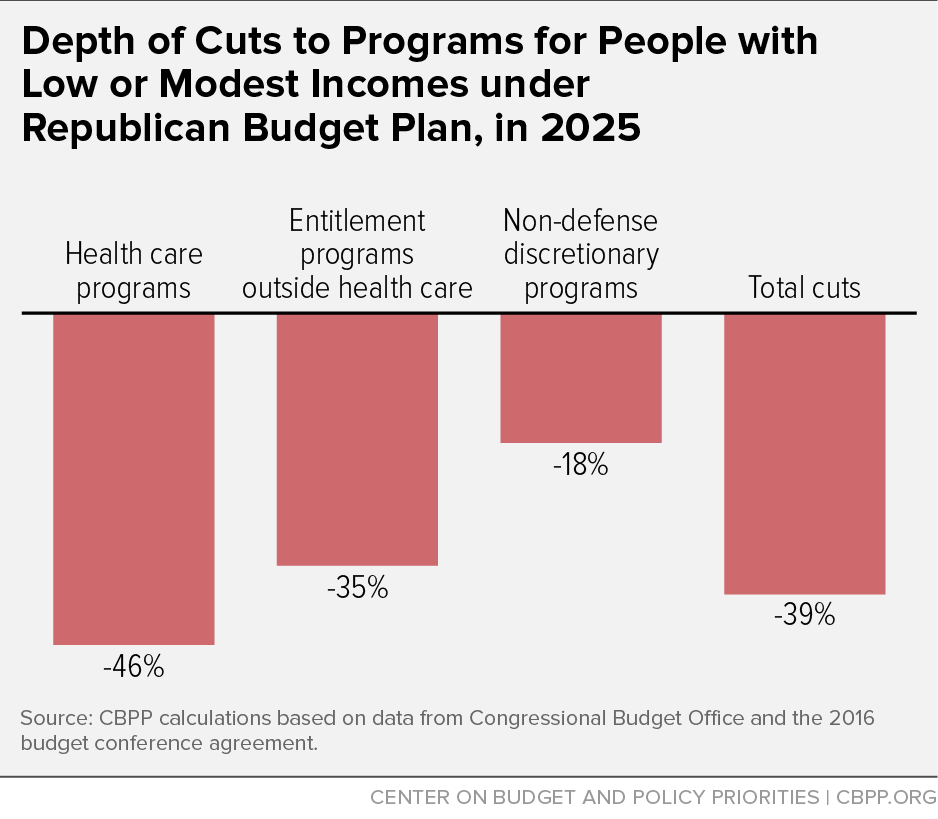

Total federal spending on programs for people with low and modest incomes is already scheduled to decline as a share of the economy over the decade under current policies.[4] With the cuts the budget imposes, spending on these programs would shrink below these levels by at least 39 percent, on average, by 2025. (See Figure 3.) The deepest reductions occur in health programs.

Overall, the budget cuts federal spending outside Social Security, Medicare, and interest payments on the debt to 7.2 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2025 — roughly 40 percent below the 12.2 percent average over the past four decades. Currently, such spending is 11.3 percent of GDP, already below its historical average. The budget plan pushes it far below that, and well below the previous post-World War II low of 9.4 percent of GDP.

Health Care Programs

The $4.9 trillion reduction over the next decade includes more than $2.7 trillion in health care cuts, the vast majority of which would affect low- and moderate-income households. As Figure 3 shows, the budget would cut health care support for such households by 46 percent — or by nearly half — by 2025. The plan repeals the Affordable Care Act (ACA), including health reform’s subsidies, which make marketplace coverage affordable for people with low or modest incomes, and its Medicaid expansion. To date, the ACA coverage expansions have extended coverage to an estimated 16.4 million previously uninsured people and strengthened coverage for millions of others.

The plan would also reduce funding for the rest of the Medicaid program by about $500 billion over ten years. Although it does not clearly specify how these cuts would be achieved, it signals its support for proposals that would fundamentally restructure Medicaid by capping federal funding through block grants or a “per capita cap.”[5]

In addition, the plan calls for cutting Medicare by $431 billion over the decade. The Medicare cuts are significantly deeper than those the President proposed, and are deeper than those proposed in the separate House and Senate budgets.

Entitlement Programs Outside Health Care

The budget plan cuts entitlement programs outside of health care by $1.5 trillion over the next decade. About half of these cuts are to entitlement programs focused on low- and moderate-income households. On average, the plan cuts low- and moderate- income entitlements outside of health care by one-third by 2025.

The plan’s reductions include:

-

Nearly $150 billion in cuts to mandatory education and social service programs, with the bulk coming from Pell Grants. The budget eliminates the mandatory portion of funding for Pell Grants, which help students from families with modest incomes afford college — a cut of about $80 billion. The budget also squeezes the other source of Pell funding, which is provided through the appropriations process. As a result, policymakers would likely have to significantly restrict eligibility or cut benefits for Pell.[6]

The remaining cuts in this category would come from other education programs, such as student loans, as well as low-income programs such as grants to states for social services and child welfare services.

- About $160 billion in cuts from allowing tax credits for low- and modest-income working families to expire. The budget plan allows critical provisions of the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC) that were enacted in 2009 to expire at the end of 2017. This would cause more than 16 million people in low-income working families, including 8 million children, to fall into — or deeper into — poverty. The plan also allows the American Opportunity Tax Credit to expire at the end of 2017, causing millions of low- and moderate-income families to lose some or all of the tax credits they receive to help offset college costs.[7]

-

Roughly $590 billion in cuts to income security programs, many serving low-income Americans. The budget plan cuts about $590 billion from mandatory programs in the “income security” category of the budget. The budget provides essentially no specifics, but we conservatively estimate that about $350 billion comes from low-income programs. Candidates include school lunch and other child nutrition programs; the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly the Food Stamp program); Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for the elderly and disabled poor; foster care and adoption assistance; the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program; child support enforcement; child care grants to states; and the refundable EITC and CTC (in addition to allowing the 2009 improvements in these tax credits to expire, as discussed above).

It is possible that the low-income cuts in the income security category could be more than $350 billion, in part because this budget category also includes programs such as military retirement. Since we apply the unspecified cuts in this spending category proportionately, we assume that the budget would cut military retirement significantly. If one assumes that congressional Republicans would not want to cut military retirement, then the remaining programs, including the low-income programs in this category, must be cut more deeply than we assume.

- About $620 billion of additional unspecified cuts to mandatory programs. About $280 billion of these cuts are allocated to broad budget categories, such as energy and agriculture, but the affected programs in those categories have not been identified. But the majority of these unspecified cuts — about $340 billion — are to mandatory funding where the type of programs at issue cannot even be discerned.[8] For lack of any alternative, we assume these cuts are distributed proportionally across all remaining mandatory spending in the budget.[9]

Non-Defense Discretionary Programs

The 2011 Budget Control Act established caps through 2021 that limit funding for defense and non-defense discretionary programs. As dictated by the BCA, these caps were subsequently lowered by a process called “sequestration,” following the failure of Congress to enact additional deficit reduction required by the BCA.[10] The 2013 budget agreement negotiated by then-House Budget Committee Chair Paul Ryan and then-Senate Budget Committee Chair Patty Murray eased some of the additional cuts required by sequestration in 2014 and 2015.

The Republican budget plan, however, provides no relief from the existing strict sequestration caps for non-defense discretionary programs in 2016. Then in the nine years after 2016, it calls for cutting funding on non-defense programs subject to the sequestration caps by another $496 billion. This component of the budget more than doubles the already scheduled large cuts in non-defense discretionary programs over the coming decade.

Non-defense discretionary programs include education, job training, infrastructure, scientific and medical research, veterans' health care, child care, and various other important areas. Roughly one-third of non-defense discretionary programs assist Americans with low and moderate incomes.

In addition to reducing non-defense funding subject to the caps by $496 billion over ten years, the budget reduces amounts for certain non-defense discretionary programs that are provided outside the caps. These include the Highway Trust Fund, “program integrity” activities to combat fraud and overpayments, and assistance provided after disasters and emergencies. As a result, our analysis finds that the budget plan would cut spending for non-defense discretionary programs by a total of $690 billion over ten years. The budget’s deep cuts to these programs would occur even though, under current law, non-defense discretionary spending will fall by 2017 to its lowest share of the economy on record (with data available back to 1962).

The budget cuts to highway and mass transit funding would be severe, amounting to 40 percent over the coming decade. These Highway Trust Fund programs are funded by gas tax revenues, which have fallen as fuel efficiency has risen, leaving a shortfall in the financing of highways and mass transit. Rather than finding sufficient additional financing, as Congress has routinely done in recent years, the plan shrinks needed investment in transportation infrastructure sharply in an apparent effort to limit spending to what the reduced level of gasoline tax revenues can support over the decade.

The budget cuts to “program integrity” activities to fight fraud and abuse in Medicare, Medicaid, and disability programs would also be significant. These program integrity activities have a proven track record of saving more than they cost. In 2012-2014, for example, each dollar spent to detect and stop erroneous payments and outright fraud in Medicare and Medicaid generated about $8 in savings.[11] The BCA allows for additional funding for program integrity activities outside the caps, and previous Congresses have exercised this option to provide resources that have accounted for the bulk of program integrity funding. The new plan eliminates all program integrity funding outside the caps.

For 2016, the Republican budget plan purports to hold both defense and non-defense discretionary funding to the sequestration level mandated by the BCA. While it offers no sequestration relief plan for non-defense programs, the plan embraces a gimmick to circumvent the cap on defense funding by pouring $96 billion into Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) — or $38 billion more than what the Pentagon says it will need for overseas military operations. Because OCO funding does not count against the defense cap, the budget plan is designed to enable the Pentagon to channel these excess dollars into the regular or “base” defense budget.

While many have suspected that some OCO funds spilled into the base defense budget in previous years, policymakers widely viewed the blatant use of OCO to fund base budget programs as an unacceptable gimmick. Indeed, just a year ago House Republicans declared it “a backdoor loophole that undermines the integrity of the budget process.”[12]

With this extra $38 billion of OCO funding, the budget matches the President’s request for the base defense budget. But the Administration has rejected the OCO approach, threatening to veto any bill that seeks to implement the gimmick. Rather, the President proposes replacing sequestration cuts with alternate savings and raising both the defense and non-defense caps by equal amounts, along the lines of the 2013 Murray-Ryan bipartisan budget agreement.

The budget reflects the level of revenue in the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) March 2015 baseline. The baseline reflects current law and thus assumes the expiration of all tax cuts that are scheduled to expire under current law. While this level of revenue is consistent with Republican leaders’ claim that their budget does not assume any new revenue, it is inconsistent with other budget assumptions — and various actions that House Republicans have taken — that embrace large new tax cuts.

For instance, Republican leaders are clear about their desire to repeal health reform, including its roughly $1 trillion of revenue increases over ten years. But the revenues in the budget are equal to the total federal revenues each year as if these revenue-raising provisions remained in effect. Either the budget overstates revenues and understates deficits by about $1 trillion or it assumes offsetting tax increases that are not described.

Furthermore, the House has continued to pursue tax policies that lose substantial revenue. It has voted to repeal the estate tax; repeal would cost $269 billion over the next decade while benefiting the estates of only the wealthiest 0.2 percent of Americans.[13] Similarly, the House has voted to make permanent (and in some cases expand) a number of mostly business-related tax breaks that expired at the end of 2014. Such legislation would lose $304 billion in revenue over ten years.[14]

By eschewing revenue increases of any sort, the budget makes no effort to reduce tax expenditures — the more than $1 trillion a year in deductions, exclusions, credits, and other preferences that former Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan has called “tax entitlements” and former Reagan economic adviser Martin Feldstein has said are the best target for cutting wasteful government spending. Tax expenditures tilt heavily toward the affluent, with two-thirds of their benefits going to the top fifth of households.

The budget resolution included a number of process provisions that affect how Congress considers future budget-related legislation. The most significant provision allows Congress to use an expedited process called “reconciliation” for considering certain budget legislation this year.[15] In the Senate, reconciliation bills aren't subject to filibuster and the scope of amendments is limited, providing significant procedural advantages for acting on controversial budget measures.

Another significant provision requires the Congressional Budget Office (and the Joint Committee on Taxation or JCT) to provide estimates of the macroeconomic effects of certain bills. These estimates — known as “dynamic scoring” — have been provided only as supplemental information in the past. The budget resolution requires they be included as part of CBO’s official cost estimates for major legislation. The main motivation for this requirement seems to be a desire to reduce the estimated cost of tax-cutting legislation.

Reconciliation

As permitted under the Congressional Budget Act, the budget resolution included reconciliation instructions to certain authorizing committees to develop legislation “to reduce the deficit.” This legislation could change spending and revenues.[16]

The instructions require that five committees — the Finance Committee and the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee in the Senate; and the Ways and Means Committee, Energy and Commerce Committee, and Education and Workforce Committee in the House — each develop legislation not later than July 24, 2015, that would reduce the deficit by at least $1 billion over 2016 to 2025. Consistent with the Budget Act, the official instructions do not indicate the specific changes the committees are expected to make to achieve this deficit reduction. But the report accompanying the budget resolution states the intent is to use reconciliation for “the sole purpose of repealing the President’s job-killing health care law.”

Although the required amount of deficit reduction — $1 billion over ten years for each reconciled committee — is small, the reconciliation legislation could have much larger budget effects, as these targets are merely minimum floors for the deficit reduction to be achieved. Most likely the targets were set very low to give the committees maximum flexibility in achieving their policy goals. The specific nature of the reconciliation legislation is likely to be heavily affected by the outcome of the Supreme Court decision on the King v. Burwell case regarding the availability of federal subsidies to individuals who purchase health insurance through federally run health insurance marketplaces.

In addition, while the report on the budget agreement expresses an intent to use reconciliation to repeal health reform, there is nothing in the reconciliation process that would preclude Congress from using it to cut programs beyond those related to health reform. The five committees that received reconciliation instructions have jurisdiction over many programs besides the Affordable Care Act. In particular, the Ways and Means and Finance Committees have jurisdiction over a range of anti-poverty programs such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, Supplemental Security Income, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.[17] Thus there remains a risk that reconciliation could be used to pursue some of the budget resolution’s assumed cuts in various programs.

As noted, the budget resolution directs the specified committees to transmit legislation consistent with their instructions to the House and Senate Budget Committees by July 24. The Budget Committees will then compile the recommendations — without making any substantive changes — into reconciliation bills for consideration by the full House and Senate. As with all legislation, once the House and Senate have passed their respective reconciliation bills, they must resolve the differences between the two measures and pass a common bill in both chambers before it can be sent to the President for his signature or veto.

Dynamic Scoring

The budget resolution requires CBO cost estimates for “major legislation” to incorporate the budgetary effects predicted to result from a bill’s effect on the economy. Major legislation is defined as a bill that has a budgetary effect in any year larger than 0.25 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) or that the chair of the Budget Committee designates as “major.” This requirement is very similar to language incorporated into the Rules of the House of Representatives at the beginning of the year, so the main effect of the budget resolution provision is to extend these practices to the Senate.

CBO cost estimates (and JCT estimates for tax legislation) have typically assumed a variety of changes in the behavior of individuals or corporations in response to policy changes, but they have not included the effects of these policies on the overall size of the U.S. economy. “Dynamic estimates” that do include these macroeconomic effects have typically been provided as supplementary information, reflecting the high degree of uncertainty around these estimates.[18] For instance, the JCT’s 2014 analysis of former House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp’s tax reform proposal used two different economic models and many different assumptions, resulting in eight separate — and widely disparate — estimates of the macroeconomic and budgetary effects of the plan.

The new requirement, by integrating dynamic scoring into the official cost estimates, could facilitate congressional passage of large cuts in tax rates by making such cuts appear — on paper — less expensive than under a traditional cost estimate. [19] That's because dynamic cost estimates are likely to show some tax reform packages boosting economic growth and thereby generating additional revenue. (This outcome is even more likely when one considers that the Republican leadership can effectively designate which bills are “major” and thus subject to dynamic scoring.) By lowering the package’s official cost, dynamic scoring could create apparent budgetary room for even deeper tax-rate cuts or lessen the need for measures to offset the rate cuts’ cost.

If tax legislation were enacted using a dynamic scoring estimate and then the assumed “dynamic” revenues failed to materialize, the legislation would add to deficits, aggravating the nation's long-run fiscal challenges and intensifying pressures for cuts in social programs. In contrast, the current rules are more prudent: if a bill boosts the economy and produces lower deficits than estimated, the nation’s fiscal outlook improves; but if no economic boost occurs, then deficits do not widen because extra revenue wasn’t assumed.

The severity of the consequences of the congressional budget plan will depend largely on how two debates play out.

The first debate will occur around the implementation of reconciliation instructions. The contours of this debate will not become clear until the Supreme Court issues its decision in June on the King v. Burwell case, which could result in the elimination of subsidies for the 6.4 million people who have purchased health insurance in states with federally run health marketplaces. The outcome of the King decision will influence the contours of the Republican majority’s plan to repeal and/or replace the ACA through reconciliation. The President, however, has made clear he will veto a reconciliation bill that dramatically changes the ACA. Particularly if the decision in King v. Burwell results in significant changes to the ACA, however, a veto may only be a prelude to negotiations over how to modify the ACA.

Around that time, it will also become clearer if the Republican majority intends to use reconciliation just for its stated intent with respect to the ACA, or if it will also use this process to attempt to enact significant cuts and other changes in other entitlement programs.

A second debate will occur around the funding of discretionary programs for fiscal year 2016 (which starts October 1 of this year). This debate has already begun in a piecemeal fashion, as some individual appropriation bills funding particular areas for 2016 wind their way through Congress. It remains to be seen how many of these bills, which keep to the BCA’s tight funding limits, Congress will be able to pass. Even so, the President has also threatened to veto any bill that adheres to these limits, calling instead for negotiations to provide some relief from sequestration. Therefore, this fall Congress and the President will likely attempt to reach agreement on providing some relief from the sequestration caps for the next year or two.

The key issues will be the offsets to pay for sequestration relief and whether the relief is shared equally between defense and non-defense programs. The Murray-Ryan budget agreement paid for sequestration relief in 2014 and 2015 using a combination of cuts to mandatory programs and increases in user fees and other receipts, and the relief was divided equally between defense and non-defense programs. Cuts in entitlement programs are likely to be a significant part of the offsets used to pay for sequestration relief for discretionary programs, and Republican negotiators could push some of the damaging proposals assumed in the budget.

Finally, it is possible that these two tracks could come together later in the year and could become enmeshed in debates over raising the debt ceiling or other outstanding budget issues. But in the final analysis, it is the outcome of these debates — rather than details of the budget resolution — that will largely determine the nature of any spending reductions that may be adopted this year, including those that may prove damaging to low- and moderate-income families and individuals.

All changes in budget policies are shown relative to an underlying spending and revenue path, referred to as the “baseline.” The figures used in this analysis rely on the CBPP baseline for the next decade. Our baseline is derived directly from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) baseline, with some relatively modest adjustments. A full description of the CBPP baseline can be found in the Technical Note to “Low-Income Programs Not Driving Nation’s Long-Term Fiscal Problem,” updated March 12, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3772.

The share of total cuts imposed on low-income programs is essentially the same no matter which baseline is used. The share of the cuts hitting low-income programs is 63 percent using the CBPP baseline and 62 percent using the unadjusted CBO baseline. The main reason we have a slightly higher figure is that we count the congressional plan to allow certain refundable tax credits to expire after 2017 as a cut, while the CBO baseline does not.

In addition, CBO is constrained by law to produce a baseline that assumes funding for overseas military operations (principally in Afghanistan and Iraq) will grow each year with inflation. CBPP, as well as the House and Senate Budget Committees, build baselines in which lower war funding is assumed in future years, consistent with current U.S. policy. Finally, CBPP projects that funding for discretionary programs will grow with population and prices after 2021, when the defense and non-defense caps set in the 2011 Budget Control Act expire, while CBO projects it to grow only with prices.