- Home

- Federal Budget

- Congress Should Reject Proposals To Cut ...

Congress Should Reject Proposals to Cut Non-Defense Program Funding

Congress is likely to engage in major battles over appropriations this year, particularly for budget areas other than defense. Unlike entitlement programs such as Social Security or Medicare, funding levels for appropriated programs must be enacted annually, and the Republican majority in the House of Representatives clearly intends to make significant cuts on the non-defense side when the House takes up 2024 funding bills.[1]

Such cuts — or even failure to keep up with rising costs — would be misguided and damaging to the government’s ability to provide services, assist people in need, and make necessary investments.

Non-defense appropriations — often referred to as “non-defense discretionary” (NDD) funding — support a wide range of important services. They fund pre-K, K-12, and higher education, medical care for veterans, scientific and medical research, housing and other assistance for families with low incomes, public health measures, treatment for people with substance use disorders, services for small businesses, weather forecasting, national parks and forests, public transportation, the Coast Guard, international aid, air traffic control, rural development programs, upgrades to wastewater and drinking water treatment, job training, and many other things.

This year’s appropriations should be seen in the context of relative austerity since 2010, resulting largely from the tight limits on annual defense and non-defense appropriations set by the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA) for 2012 through 2021. The starting point for those caps was the 2011 level, effectively locking in substantial cuts in non-defense programs that had been made that year.

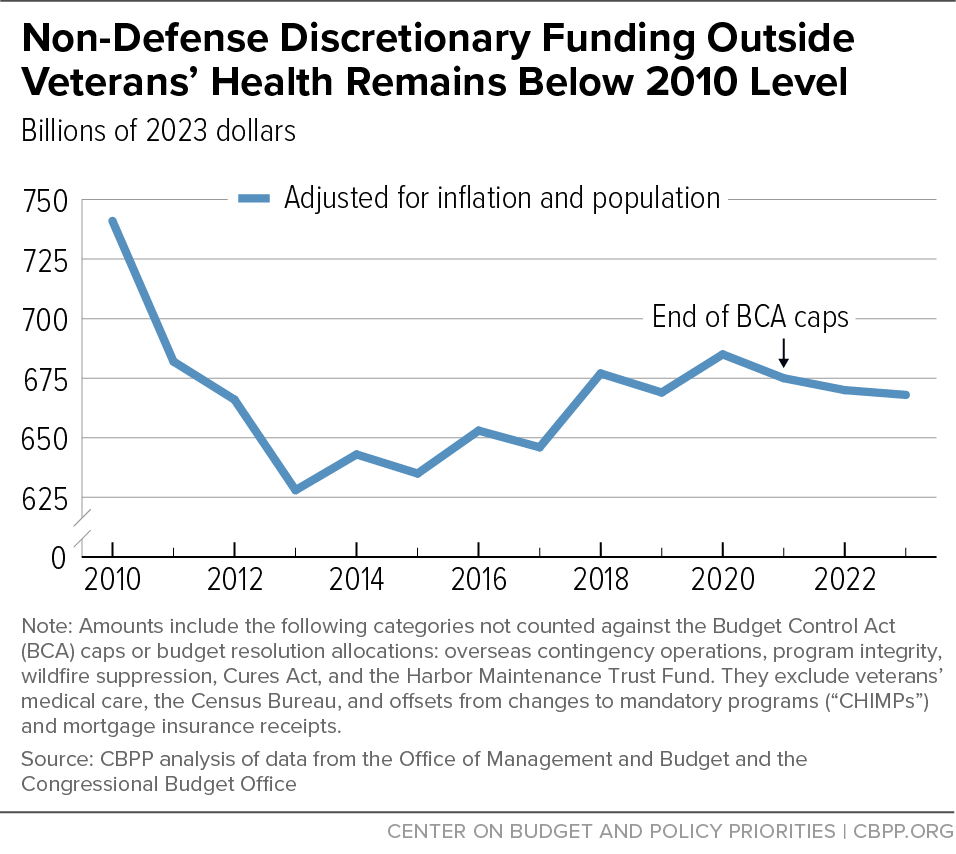

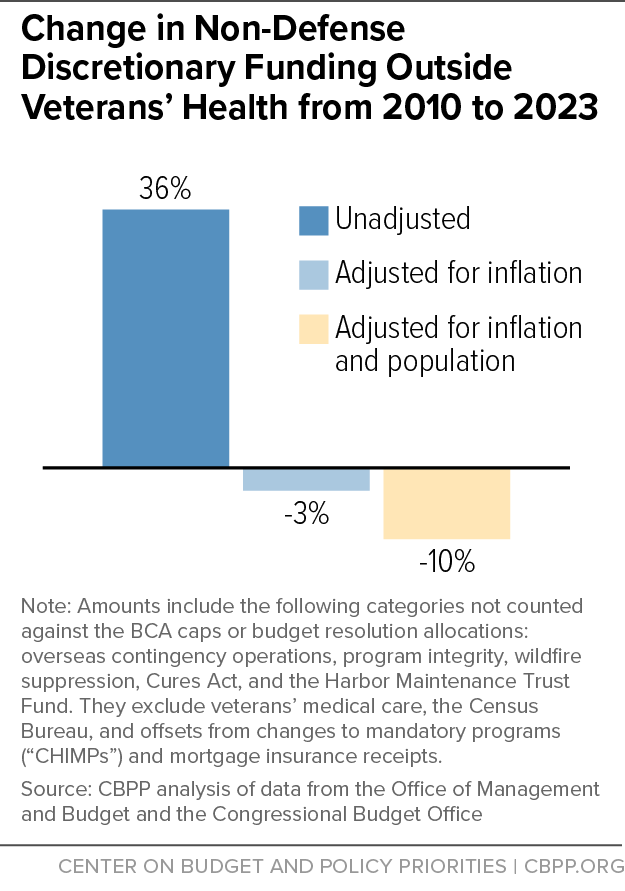

Looking over multi-year periods requires accounting for factors that affect costs and needs. Prices, and hence program costs, rise over time; this has been true particularly in recent years, when inflation surged. The nation’s population also continues to grow, increasing the number of people that the federal government serves while spreading the costs of programs among a larger population. While overall NDD funding has risen above the BCA’s low point in 2013, by 2023 it was still 2 percent below what it had been 13 years earlier after adjusting for inflation and population growth. (This paper compares BCA funding levels to those in 2010 because Congress began cutting NDD programs in 2011, and that initial round of cuts was the base for the BCA caps.)

Fully understanding the squeeze on most non-defense appropriations requires also looking at the role of veterans’ medical care, which is funded almost entirely through NDD appropriations and is the largest program in that category, accounting for almost one-sixth of the total. For good reason, Congress has placed high priority on meeting veterans’ health care needs. The cost of doing so has been rising much more rapidly than the overall NDD total, due to factors such as increasing numbers of veterans using the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health system, rising health care costs in general, and some expansion of health benefits.

As a result, overall 2023 funding for NDD programs other than veterans’ medical care remains 10 percent below its 2010 level after adjusting for inflation and population growth. (See Figure 1.) And as Figure 4 in this paper shows, reductions were spread across most categories of the federal budget.

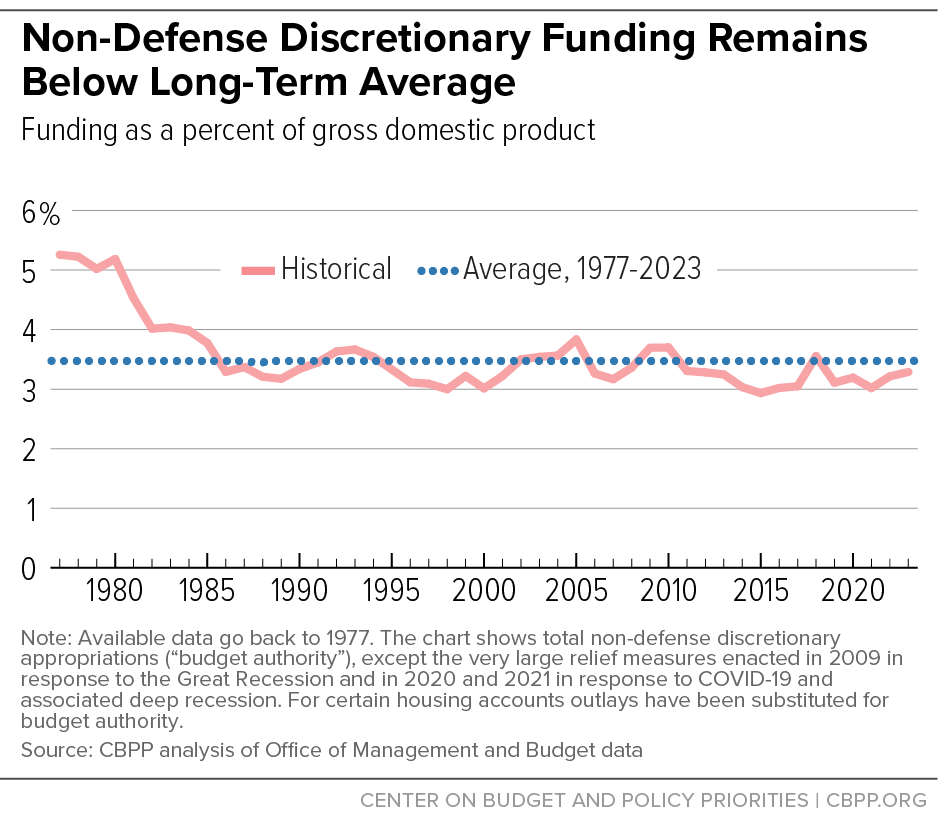

Another way of looking at budget trends is to measure funding relative to the size of the economy, as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). On that basis, too, the current NDD funding is not particularly high. In 2023 it’s an estimated 3.3 percent of GDP, compared with 3.7 percent in 2010 and an average of 3.5 percent over the full period since 1977. Excluding veterans’ medical care, it is 2.8 percent of GDP in 2023, compared with 3.4 percent in 2010 and an average of 3.3 percent since 1977.

These topline numbers translated into under-funding in a wide range of NDD programs and services, either because the area was cut or, even if the area didn’t sustain cuts, the lack of adequate investment has left large unmet needs. Here are a few examples:

- Because of funding limitations, federal housing assistance serves only 1 in 4 eligible households, leaving 7.8 million households with very low incomes paying more than half their income for rent or living in severely substandard housing.

- Appropriations for aid to K-12 education — which is largely targeted to increasing opportunity and promoting success for students from low-income families and students with disabilities — decreased by 15 percent between 2010 and 2023 after adjusting for inflation.

- Funding shortfalls for the Social Security Administration (SSA) caused it to lose 13 percent of its staff since 2010, hampering its ability to perform basic services such as answering questions and processing applications for benefits in a timely and accurate way.

- The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) budget was cut by 30 percent between 2010 and 2023, adjusted for inflation. These cuts affected most aspects of the agency’s operations such as the reduction and cleanup of pollution; enforcement of regulations; help to state, local, and tribal environmental agencies; and scientific research.

In sum, there’s no evidence that NDD funding is too high or rising too rapidly, while there is considerable evidence of unmet needs that have negative impacts on people and communities, limiting opportunity and harming well-being. In the coming year, Congress should work to set non-defense appropriations at a level adequate to meet national priorities, remedy shortfalls that hamper delivery of government services, and help build a stronger and more equitable economy — and should reject proposals to go backward, leading to larger investment shortfalls that would undermine efforts to build a nation where everyone can thrive.

What Do Non-Defense Appropriations Fund?

Non-defense appropriations — also known as non-defense discretionary funding — support a wide range of federal activities, investments, and assistance. The category is called “discretionary” because Congress has the discretion to set funding levels through the annual appropriations process, distinct from entitlements and other “mandatory” programs, where funding is determined by the underlying law governing the program. The analysis in this paper focuses on regular appropriations for ongoing programs and services — as Congress will soon be considering for fiscal year 2024 — but not special funding to deal with natural disasters and other emergencies, including emergency funding appropriated in response to the pandemic.

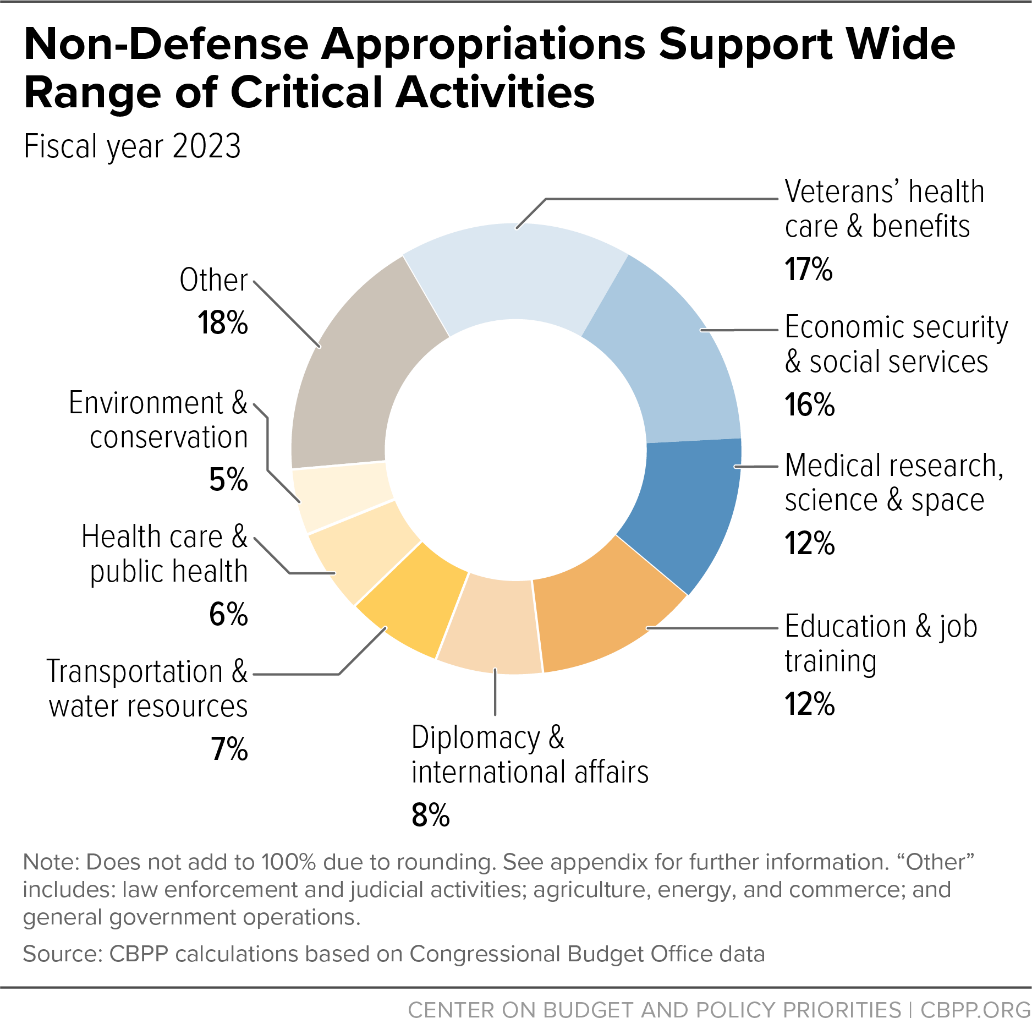

The following are some of the diverse and important program areas funded by non-defense discretionary appropriations (see Figure 2 and Appendix Table 1):

- Health care and other services for veterans. This is now the largest category within non-defense appropriations, making up roughly one-sixth of the 2023 total. About 90 percent is for veterans’ medical care. The remaining amounts are mostly for the operating expenses of the Department of Veterans Affairs, including administrative costs for benefits supported with mandatory funding.

- Economic security and social services. NDD appropriations also fund important supports for people with low incomes. Examples include housing assistance, Head Start, Low-Income Home Energy Assistance (LIHEAP), the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and Older Americans Act programs, along with part of child care assistance. This category also covers the administrative expenses of Social Security, other retirement programs, and unemployment insurance.

- Medical and scientific research and space exploration. This is another area where almost all federal funding comes through NDD appropriations. Of the total appropriated in 2023, more than half is for research and training at the National Institutes of Health and other health agencies. Most of the rest is for NASA, the National Science Foundation, and Department of Energy labs.

- Education and job training. NDD appropriations provide almost all federal support for elementary, secondary, and vocational education and for job training, as well as about three-quarters of federal support for higher education (including Pell Grants and other student financial aid). About half of this year’s total is for K-12 education.

- Public health and health services. NDD appropriations are also the main source of federal funding for public health programs at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other Department of Health and Human Services agencies. They also support grants for treatment of opioid addiction and other substance use disorders and for mental health services, as well as the Indian Health Service and various other health care programs.

- Transportation and water resources. NDD appropriations play an important role in infrastructure investments, including by funding the navigation, flood control, and other civil works projects of the Army Corps of Engineers and various programs at the Department of Transportation (such as air traffic facilities and equipment, mass transit capital funding, and railroad programs).[2] This category also includes operating expenses of those agencies.

- Environment, national parks, and conservation. About four-fifths of funding for programs in this category comes through NDD appropriations. This funding goes to support the activities of the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Park Service, the Forest Service, the Fish and Wildlife Service, and several other conservation and land management agencies, as well as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

In addition to the areas mentioned above, NDD appropriations support a wide variety of other important functions and services, such as law enforcement and federal courts; the Small Business Administration; the State Department and international assistance programs; the Internal Revenue Service; agricultural research and services; the Census Bureau and other statistical agencies; and economic and community development programs.

The Context for 2024: More Than a Decade of Austerity in Appropriated Funding

Current appropriations should be seen in the context of the considerable austerity in non-defense funding that prevailed during the last decade.

For much of the past decade, appropriations totals have been governed by the Budget Control Act of 2011 and a series of amendments to that law. The BCA was enacted as part of agreements that ended a stalemate over a needed increase in the federal debt ceiling. It created a series of tight caps on appropriations extending ten years into the future, which were further reduced by the additional cuts (referred to as “sequestration”) triggered by the failure of a congressional Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction to reach agreement on other deficit-reduction measures. There was no particular policy or economic rationale for these cuts. Rather, they were intended to be so unacceptable as to produce a broader budget agreement in order to avoid them. That strategy failed, leaving in place a series of appropriations limits that had been designed to be unacceptable.

The low point was in 2013, as the sequestration process triggered by failure of the Joint Select Committee began, leaving overall inflation-adjusted NDD funding 12 percent below its 2010 level.[3]

NDD funding gradually increased from this BCA low point after 2013, reflecting the series of agreements that amended the BCA two years at a time, scaling back the sequestration cuts and, starting in 2018, providing modest increases above the pre-sequestration caps. In 2021, the last year of BCA caps, inflation-adjusted NDD funding was 3 percent above its 2010 level. When adjusted for both inflation and the growth in the U.S. population, which is important to consider when looking over extended periods given the increasing needs of a growing population, NDD funding in 2021 was 3 percent below 2010. And, as discussed in more detail below, discretionary program funding outside of veterans’ health care was even further below the 2010 level adjusted for inflation and population growth.

Appropriations After the BCA Caps Expired

After the BCA caps expired in 2022, policymakers returned to the long-standing practice of deciding funding levels for appropriations each year. An important factor in making decisions for 2022 and 2023 was the fairly high rate of inflation, which increases the costs of operating programs and providing services. The inflation rate was 7.9 percent in 2022 and CBO estimates it will be 5.7 percent in 2023 — well above the average of 1.6 percent over the previous decade.

As a result, despite the significant increases enacted, overall NDD funding adjusted for inflation and population in 2023 is only 1 percent above the 2021 level and is still 2 percent below the 2010 level (and further below when looking at all areas other than veterans’ medical care).

The Role of Veterans’ Medical Care Costs

For most of the programs within the NDD category, the constraints were tighter than the totals suggest. That’s because of substantial funding increases needed to maintain and improve veterans’ medical care, which is the largest program funded by non-defense appropriations. Veterans’ medical care funding rose 87 percent between 2010 and 2023 on an inflation-adjusted basis. That increase was largely concentrated in the latter part of the period, with the annual inflation-adjusted growth reaching 15 percent in 2023. These rising costs have a substantial effect on NDD as a whole because veterans’ medical care now accounts for almost one-sixth of all NDD funding.

The growth in veterans’ medical funding reflects the high priority that Congress places on meeting veterans’ needs. Contributing factors include rising health care costs in general, demographic factors, and resources needed to fix serious problems in the system such as long waiting times for care. In addition, during the past decade Congress enacted legislation (the MISSION Act of 2018) expanding veterans’ access to health care from non-federal providers and adding additional services. These developments — largely unforeseen when the Budget Control Act was enacted 2011 — are a good illustration of the drawbacks to setting arbitrary targets for appropriations years into the future.

For all NDD programs other than veterans’ medical care, inflation-adjusted funding in 2023 was 3 percent below its level 13 years earlier. (See Figure 3.) After also adjusting for population growth as well, funding for these programs decreased 10 percent from 2010 to 2023.

Cuts Will Have Continuing Effects

Looking only at the net change between the starting and ending points doesn’t capture what happened in between — namely the much larger decreases that occurred in the early and middle parts of the past decade before being partially reversed. For all years 2011-2023 taken together, NDD funding excluding veterans’ medical care was $616 billion below levels needed to keep up with inflation since 2010 and $1.0 trillion below levels needed to keep up with inflation and population growth.

That gap translates into less investment in maintaining and upgrading technology and facilities, less progress in addressing inequalities in education or housing, less support for infrastructure investments, less scientific research, less investment in children (with attendant long-term harm), and poorer service to the public by government agencies, among other consequences. Some of that represents lost opportunities to assist and serve. In other cases, deferred maintenance and investments in technology and infrastructure not made will lead to higher costs in the future.

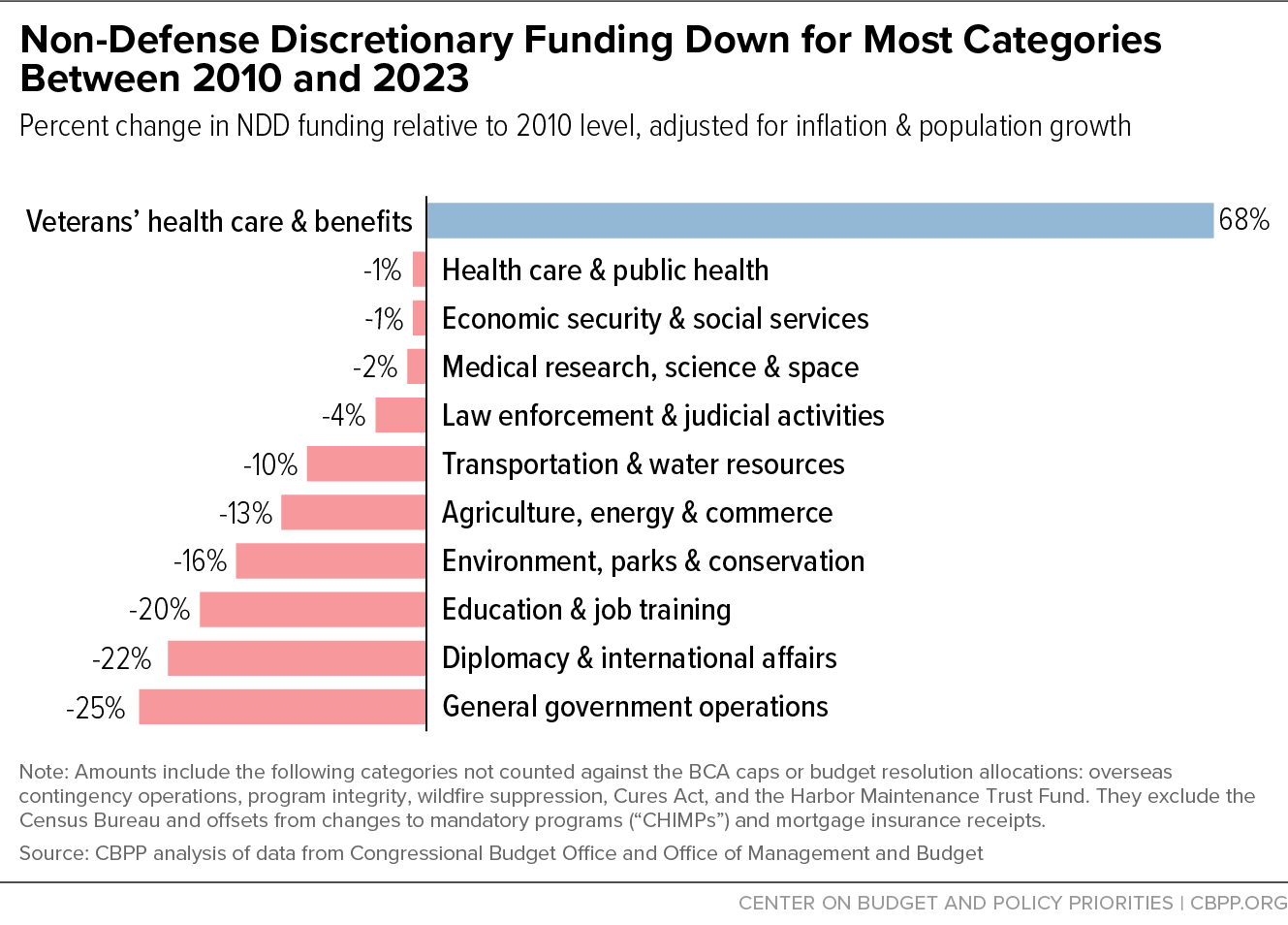

Reductions by Major Category

The reductions between 2010 and 2023 were spread broadly across the NDD budget categories. That can be seen in Figure 4, which shows funding changes over that period for broad groupings of federal programs, after adjustment for inflation and population growth. Apart from veterans’ programs, overall funding fell for each of these categories between 2010 and 2023 (though some programs within each category saw funding increases while others saw larger declines). For health care and public health the cut was just 1 percent; for environment, parks, and conservation it was 16 percent; and for education and job training it was 20 percent.

Continuing Shortfalls and Unmet Needs

These high-level trends translate into numerous specific areas of serious shortfalls and unmet needs. In many cases these are the results of funding cuts; in other cases, funding has long been inadequate to meet more than a fraction of need. Here are some examples.

Rental assistance. Federal rental assistance programs help more than 5 million households, consisting of about 10.4 million people, afford safe, stable homes. Unlike some other major forms of assistance for people with low incomes, rental assistance is supported entirely through annual discretionary appropriations and therefore is particularly vulnerable in periods of tight overall NDD funding. Moreover, costs to renew existing housing assistance increase annually with rent inflation, meaning that decreased or even flat funding leads to fewer households receiving help over time.

Rental assistance is key to addressing the gap between renters’ incomes and rising rent prices. From 2001 to 2021, median rent costs increased by nearly 18 percent, while median renter household income increased by only 3.2 percent.[4] This disparity combined with the lack of adequate funding for supports such as rental assistance to leave 7.8 million households with very low incomes either paying more than half their income for rent or living in severely substandard housing, an increase of 32 percent since 2007.[5] Due to inadequate funding, rental assistance programs only serve 1 in 4 eligible households.[6]

Without resources to keep people stably housed, additional pressure is created on the homelessness services system, another key part of NDD funding that needs additional resources, not less.

Social Security Administration customer service. As a result of more than a decade of austere operating funding, compounded by the pandemic, SSA is facing a customer service crisis. The SSA’s operating budget is set through annual appropriations, and between 2010 and 2023 that budget shrank by 13 percent after adjusting for inflation.

This forced the agency to do more with less, as funding cuts caused the agency to lose 13 percent of its staff over that period while the number of Social Security beneficiaries grew by more than 21 percent. These cuts have hampered the agency’s ability to perform its essential services, such as making timely determinations of benefit eligibility, responding to questions from the public, and updating benefits promptly when circumstances change. Hold times and busy signals on the agency’s 800 number are increasing.

Problems are particularly acute for disability applicants. Over 1 million disability claims are pending at state disability determination agencies (which are funded by SSA’s appropriation), with applicants waiting more than seven months, on average, for a decision — and if they wish to appeal, waiting two more years to complete that process.[7]

Aid to elementary and secondary education. Appropriations for the federal government’s modest but important contribution to K-12 education fell by 15 percent between 2010 and 2023, adjusted for inflation. A large majority of this federal aid is for programs that promote equity and educational opportunity for disadvantaged students and students with disabilities.

This total includes a 9 percent inflation-adjusted cut between 2010 and 2023 for grants to school districts under the “Title I” Education for Disadvantaged Students program.[8] These grants help schools provide additional services and supports to assist students from low-income families succeed. It serves roughly 25 million students who attend more than half of the nation’s schools, and helps address long-standing school funding disparities between low-income communities and their wealthier counterparts. Grants to states under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which help school districts cover the cost of special education services for more than 7 million children with disabilities, were also cut by 12 percent, adjusted for inflation, during this period.

Child care. Care for young children is often prohibitively expensive, with one study finding that families with low incomes spend 35 percent of their income on child care.[9] The largest source of federal assistance with child care costs is the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG), funded through discretionary appropriations. This block grant and related programs subsidized care for more than 900,000 families, or almost 1.5 million children, with low incomes in 2020 (the latest year with available data).[10]

However, this only represents a fraction of eligible families. HHS estimates that in 2019, before the pandemic, federal child care programs were assisting only about 16 percent of eligible children.[11] The pandemic placed great strain on providers, with many closing their doors; substantial pandemic relief was provided, but those funds will expire soon. The 2023 appropriations provided a substantial increase for the CCDBG — $1.9 billion or 30 percent. But the gap between resources and need for child care is so wide that considerably more funding will be necessary to close that gap.

Financial aid for college students. Annual appropriations currently provide more than three-quarters of the funding for Pell Grants, which are the foundation of federal financial aid for college students from low- and moderate-income families. More than one-third of all undergraduate students receive these grants, which vary in amount according to income and need. This support is particularly important to students of color, whose families on average have lower income and less wealth than white students. In academic year 2020-2021, about 65 percent of Pell Grant recipients had incomes of $30,000 or less.[12]

The purchasing power of Pell Grants has shrunk dramatically over the past several decades, reflecting funding levels that have not kept up with costs. In academic year 1980-81 the maximum Pell Grant would have covered 69 percent of average in-state tuition, fees, and room and board costs at public four-year colleges and universities. By 2010-11, that share had fallen to 34 percent, and despite some modest increases in grant amounts by 2022-23 it was down to 30 percent.[13] The 2023 appropriations legislation increased the maximum Pell Grant by $500 for 2023-24. While estimates of college costs in that year are not yet available, if costs rise at the same rate as they did in 2022-23, the share covered by the maximum Pell Grant will rise only slightly, to 31 percent.[14]

Environmental protection. The EPA’s budget was cut by 30 percent, adjusted for inflation, between 2010 and 2023 — one of the largest cuts to any major agency — and its staff was cut by 13 percent over that same period. These reductions affected most areas of EPA operations, including scientific activities, regulatory and enforcement programs, cleanup of Superfund hazardous waste sites, and assistance to state, local, and tribal agencies.

Job training. Appropriations for job training programs were cut by 23 percent from 2010 to 2023, adjusted for inflation.[15] These programs largely operate through state and local agencies and are designed to support individuals facing barriers to finding and maintaining employment. There are separate funding streams for adult workers, youth, and “dislocated” workers who lost jobs due to events such as mass layoffs or disasters, as well as for some smaller programs such as those targeted to migrant and seasonal farmworkers and people exiting the criminal justice system.

Legal services. The Legal Services Corporation (LSC) supports more than 130 independent nonprofit legal aid agencies throughout the country. These agencies provide legal assistance to people and families with incomes at or below 125 percent of the federal poverty line in non-criminal legal matters involving things like housing, family issues (adoption, child custody, domestic abuse, and divorce), access to health care, income support and other benefits, employment law, and consumer finance and debt collection.

LSC appropriations were increased from $489 million in 2022 to $560 million in 2023, though the 2023 level is still 5 percent below 2010 after adjustment for inflation. The long-term cuts have been considerably steeper: adjusted for inflation, 2023 LSC funding is 48 percent below its 1980 level. A recent study by the LSC estimated that, due to limited resources, its grantee agencies were able to provide even limited help for only about half the legal problems brought to them.[16]

Non-Defense Appropriations Remain Below Long-Term Trends

Another standard way to look at budget levels over time is as a percentage of GDP, an approach that puts funding in the context of the economy. Data on this basis are available for appropriated funding back to the mid-1970s and are shown in Figure 5. These long-term data include all classifications of NDD funding, including most emergency funding, because it isn’t feasible to remove from the historical data all appropriations that responded to natural disasters and other emergencies. However, the line in Figure 5 does exclude more recent, large emergency appropriations, including for the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, COVID-19 responses and recovery in 2020-2021, and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, to better capture ongoing funding.

From 1977 through 2023, NDD funding averaged 3.5 percent of GDP. Over this period, the percentage was as high as 5.3 percent and as low as 2.9 percent. Appropriations as a percent of GDP tend to rise during recessions, as policymakers enact recession-relief spending measures at the same time GDP shrinks. The percentage usually falls as the economy returns to growth and temporary recession-relief spending expires.

NDD funding also tends to rise as a percent of GDP in years with major natural disasters or other emergencies, similarly because policymakers enact measures to respond to them. For example, NDD funding rose sharply from 3.0 percent of GDP in 2017 to 3.6 percent in 2018 largely because of emergency appropriations enacted to address the consequences of hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria.

In 2010 NDD funding equaled 3.7 percent of GDP, measured on this basis. In 2022 it was down to 3.2 percent of GDP, and we estimate that it will be 3.3 percent under the appropriations enacted for 2023.

In short, current NDD funding relative to the size of the economy is 0.4 percentage points below its 2010 level and 0.2 percentage points below the long-term average. Moreover, the historical average itself — particularly starting in the mid-1980s — reflects a long-standing pattern of underfunding investments across a range of critical areas. As the discussion above makes clear, significant unmet needs remain.

Appendix

Basis for Funding Data Used in This Paper

Except where the text indicates otherwise, numbers used in this paper for NDD appropriations represent regular funding subject to the allocations set in congressional budget resolutions and to the BCA caps when they were in effect, along with adjustments to better reflect actual programmatic funding. The adjustments are as follows:

- Two categories of offsets to appropriations are excluded from our figures. One is changes to mandatory programs made in appropriations bills (commonly known as “CHIMPs”), which provide savings to the discretionary appropriations bill that contains them and thereby allow higher program funding within the bill. The other is fee income derived from receipts from mortgage insurance at the Department of Housing and Urban Development (FHA and GNMA). Excluding these offsets (but not the funding they offset) better focuses the analysis on actual funding for appropriated programs.

- Certain categories of funding not subject to the allocations or caps are included to provide a more complete picture of overall non-defense appropriations trends. These categories are overseas contingency operations funding for certain war-related costs of the State Department and other international agencies, program integrity funding intended to help identify and eliminate fraud and abuse in areas such as federal health care programs and disability benefits, funding to support management and control of wildfires, and funding under the 21st Century Cures Act and the Harbor Maintenance Trust Fund.

Two other categories of funding outside the allocations and caps — emergencies and disaster relief — are not included because their amounts fluctuate greatly from year to year, are unpredictable, and are not related to underlying NDD trends.

- Finally, the account that funds decennial censuses is also removed, to avoid distortions resulting from comparing decennial census years with high census costs, such as 2010, to other years.

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Further Detail on NDD Funding by Category | |||||

| Non-Defense Discretionary Funding, by Major Category | 2010 | 2023 | 2010-2023, Percent Change, Adjusted for: | 2023, Percent of Total NDD | |

| Inflation | Inflation & Population | ||||

| Veterans' Health Care & Benefits | 53.4 | 135.4 | 81% | 68% | 17% |

| Economic Security & Social Services | 83.4 | 124.1 | 6% | -1% | 16% |

| Medical Research, Science, & Space | 61.9 | 91.6 | 6% | -2% | 12% |

| Education & Job Training | 75.3 | 91.2 | -14% | -20% | 12% |

| Law Enforcement & Judicial | 52.9 | 76.2 | 3% | -4% | 10% |

| Diplomacy & International Affairs | 54.5 | 63.7 | -17% | -22% | 8% |

| Transportation & Water Resources | 42.6 | 57.5 | -4% | -10% | 7% |

| Health Care & Public Health | 32.7 | 48.6 | 6% | -1% | 6% |

| Agriculture, Energy, & Commerce | 31.8 | 41.8 | -6% | -13% | 5% |

| Environment, Parks & Conservation | 29.8 | 37.5 | -10% | -16% | 5% |

| General Government Operations | 20.7 | 23.4 | -19% | -25% | 3% |

| Total | 538.9 | 791.2 | 5% | -2% | 100% |

Note: The categories shown above are a simplified version of the standard functional classifications used in the federal budget.

Source: CBPP analysis of data from the Office of Management and Budget and Congressional Budget Office

End Notes

[1] House Republicans have reportedly pledged to roll total appropriations for 2024 back to the 2022 level. See Joel Friedman and Richard Kogan, “House Republicans’ Pledge to Cut Appropriated Programs to 2022 Level Would Have Severe Effects, Particularly for Non-Defense Programs,” CBPP, February 1, 2023, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-budget/house-republicans-pledge-to-cut-appropriated-programs-to-2022-level-would.

[2] This category does not include the highway and mass transit trust funds because that funding is considered mandatory.

[3] See the Appendix for an explanation of the numbers used for NDD funding in this paper. In general, they remove certain offsets and add certain ongoing funding outside the BCA caps to focus on programmatic funding. These adjustments make the funding levels appear higher and the increase between 2010 and 2021 larger than it would be without them. The NDD levels used in this paper do not include funding — outside the caps — for disaster relief or to address other emergency needs, since that funding varies considerably from year to year in response to natural disasters and economic or health emergencies. In particular, they do not include any of the COVID-19-related emergency funding enacted during 2020 and 2021, as the focus of this paper is on funding for ongoing needs that will remain after the COVID-19 pandemic has receded.

[4] CBPP, “Housing Costs Climbed During Pandemic While Renters’ Incomes Stagnated,” https://www.cbpp.org/housing-costs-climbed-during-pandemic-while-renters-incomes-stagnated.

[5] CBPP, “Federal Rental Assistance Has Not Kept Pace with Growing Need,” https://www.cbpp.org/federal-rental-assistance-has-not-kept-pace-with-growing-need-5.

[6] CBPP, “76% of Low-Income Renters Needing Federal Rental Assistance Don't Receive It,” https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/three-out-of-four-low-income-at-risk-renters-do-not-receive-federal-rental-assistance.

[7] For more information about SSA staffing and service delivery shortfalls, see Kathleen Romig and Luis Nuñez, “After Years of Budget Cuts, Increased Funding Would Help Social Security Administration Restore Staff and Improve Customer Service,” CBPP, November 18, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/after-years-of-budget-cuts-increased-funding-would-help-social-security-administration-restore.

[8] For more information about this program, see Jabari Cook et al., “House Appropriations Bills Take Steps to Use the Federal Budget as a Tool for Antiracism,” CBPP, February 3, 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/house-appropriations-bills-take-steps-to-use-the-federal-budget-as-a-tool-for-antiracism.

[9] Alyssa Fortner, “Investing in Child Care and Early Education Supports Families and Strengthens Families,” Center for Law and Social Policy, August 25, 2022, https://www.clasp.org/blog/investing-in-child-care-and-early-education-supports-families-and-strengthens-economies/.

[10] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Child Care, FY 2020 Preliminary Data Table 1, May 24, 2022, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/data/fy-2020-preliminary-data-table-1.

[11] Nina Chien, “Factsheet: Estimates of Child Care Eligibility and & Receipt for Fiscal Year 2019,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, September 2022, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1d276a590ac166214a5415bee430d5e9/cy2019-child-care-subsidy-eligibility.pdf.

[12] Calculated from U.S. Department of Education, Pell 2020-21 End of Year Tables, Table 3, https://studentaid.gov/data-center/student/title-iv.

[13]These percentages were calculated using the College Board’s statistics on the cost of attending college in the various years cited, “Trends in College Pricing 2022,” Table CP-2, https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fresearch.collegeboard.org%2Fmedia%2Fxlsx%2Ftrends-college-pricing-excel-data-2022.xlsx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK.

[14] For private non-profit institutions, the share of tuition, fees, room, and board covered by the maximum Pell Grant fell from 31 percent in 1980-81 to 15 percent in 2010-11 and 13 percent in 2022-23. If costs rise at the same rate as for 2022-23, the maximum Pell Grant will continue to cover 13 percent of costs.

[15] This discussion refers specifically to programs funded in the Labor Department’s Training and Employment Services account. It does not include the Job Corps.

[16] Legal Services Corporation, “The Justice Gap: The Unmet Civil Legal Needs of Low-Income Americans,” section 4, April 2022, https://lsc-live.app.box.com/s/xl2v2uraiotbbzrhuwtjlgi0emp3myz1.

More from the Authors