- Home

- Federal Budget

- Analysis Of President Biden’s 2023 Budge...

Analysis of President Biden’s 2023 Budget

CBPP Staff

President Biden’s 2023 budget calls for a range of policies that would boost opportunity and reduce poverty, improve health and well-being, and advance widely shared prosperity.[1] It would fully pay for these policies — and also reduce the deficit by $1 trillion over the next decade — by requiring well-off households and profitable corporations to pay a fairer amount of taxes.

To evaluate the Administration’s policy priorities, this budget should be viewed in conjunction with the President’s 2022 budget. While Congress adopted two bills reflecting some of the major priorities in that budget — the infrastructure package enacted on a bipartisan basis in November 2021 and the 2022 appropriations bills — the budget’s climate and economic proposals remain under consideration, as do its revenue-raising proposals and prescription drug savings to offset their cost. The 2023 budget includes a deficit-neutral reserve fund as a placeholder for these investments and offsets, but because discussions with Congress are underway, it does not lay out another round of specific proposals in these areas.

Outside of the reserve fund, the budget proposes spending and revenue policies, including details for programs funded through the annual appropriations process. Like all budgets, it includes both new policies and policies the President proposed previously that have not been enacted but that the Administration continues to champion.

Reserve Fund for Policies Under Discussion in Congress

The Administration used the release of the 2023 budget as an opportunity to reiterate its commitment to an economic package that reduces costs for families, addresses climate change, and raises revenues to pay for these investments and shrink the deficit. The budget points to priorities proposed in the President’s previous budget and under discussion in the context of the economic package, including getting health coverage to people in states that have refused to expand Medicaid; helping families afford costs such as health care and prescription drugs, child care, elder care, and housing; expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit for very low-paid workers without children; expanding the Child Tax Credit to help families with low incomes make ends meet at a time of rising costs; addressing climate change; and responsibly raising revenues on high-income households and profitable corporations.

Failure to enact a package with these provisions would have significant consequences. For example:

- More than 2 million uninsured people would remain without a pathway to coverage because they live in one of 12 states that haven’t adopted the ACA’s Medicaid expansion.

- Millions of people getting coverage through the ACA marketplace would see their premiums go up substantially when the current premium tax credit enhancements expire in December. Some might struggle but decide to pay the higher cost; others might forgo coverage and become uninsured.

- Some 27 million children in families with low or no income would receive less than the full Child Tax Credit, and an estimated 2 million children would remain in poverty due to their exclusion from the full $2,000 per child credit available under current law.

- Millions of families would fail to gain access to preschool or child care, undermining children’s future educational and employment prospects and parents’ employment opportunities and earnings.

- Hundreds of thousands of people experiencing or at risk of homelessness, overcrowding, and eviction would not benefit from a proposed expansion of housing vouchers, which have proven highly effective at addressing those problems.

- Prescription drug prices wouldn’t be reduced for seniors, as Medicare would not be given the authority to negotiate prices with drug companies and no limits would be placed on annual increases in drug prices.

- A tax code distorted by two decades of regressive tax cuts, which have suppressed revenues and widened inequality while failing to deliver the faster economic growth their supporters promised, would remain in place.

Non-Defense Priorities

The President’s 2023 budget includes detailed policies in a number of areas to broaden opportunity and enable the federal government to deliver services more effectively.[2] Some of these proposals provide multi-year funding, while others would require annual appropriations.

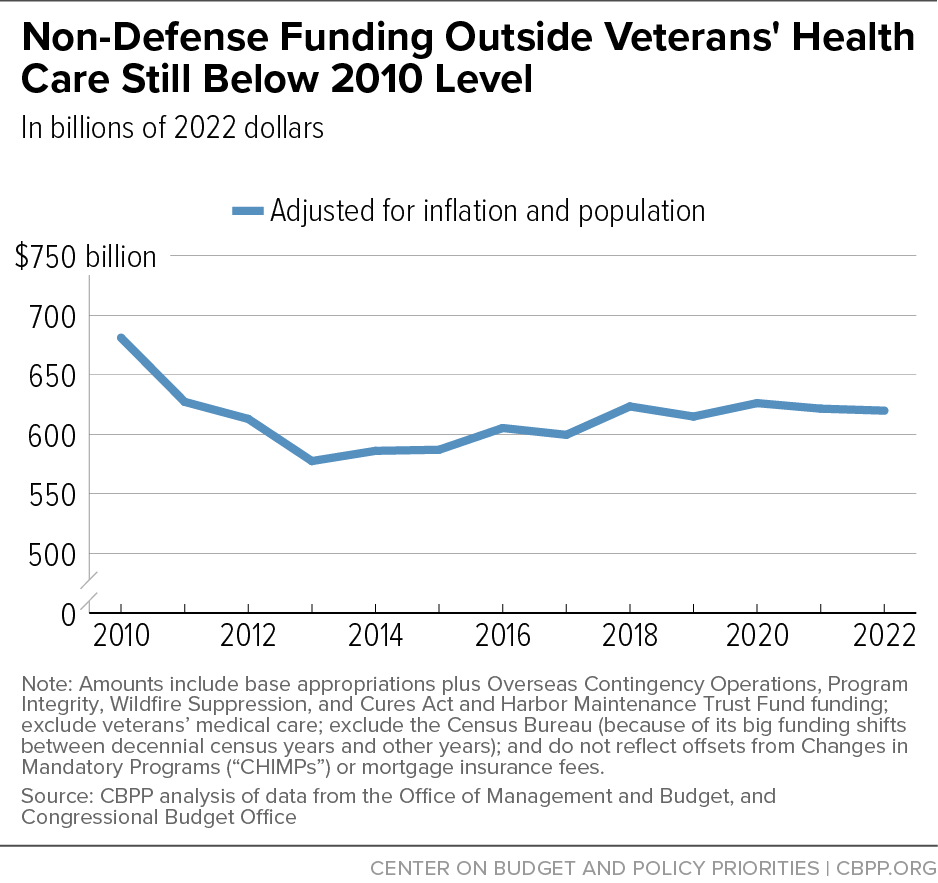

Historical underfunding in non-defense appropriations, made worse by deep cuts starting in 2011, has left many national needs unmet. The recently enacted omnibus appropriations bill for 2022 boosted non-defense funding by about 6 percent relative to the 2021 level, not accounting for inflation. Significant funding gaps remain in many areas, however. Even with the increase in the omnibus, overall non-defense funding is still about 3 percent below its 2010 level after adjusting for inflation and population growth. And the large increases needed to maintain and improve veterans’ medical care — which now accounts for roughly one-seventh of all regular non-defense funding — mean that funding in other program areas is roughly 9 percent below the 2010 level, adjusted for inflation and population. (See Figure 1.)

The President’s 2023 budget would increase non-defense appropriations by about $97 billion (13 percent) over the 2022 enacted level, not accounting for inflation.[3] Just over one-fifth of the increase would go to veterans’ medical care (a 22 percent boost); other non-defense programs as a whole would receive a 12 percent boost. While we don’t yet know the overall inflation rate for 2023, after adjusting for inflation the increase would be in the single digits. With these increases, non-defense programs outside veterans’ medical care likely would still be slightly below their 2010 level, after adjusting for inflation and population.

Notably, the budget proposes that some increases in appropriated programs, such as for Title I and the Indian Health Service (discussed more below), be funded outside of the regular appropriations process.

Expanding Access to Affordable Housing

The President’s budget would increase funding for Housing Choice Vouchers, which help people with low incomes rent modest housing of their choice in the private market, by $4.8 billion (17 percent) above the 2022 level. This increase would cover the added costs of using existing vouchers to help families stay stably housed in the face of sharply rising rent and utility costs, add resources for “mobility services” to help give voucher holders the option to rent housing in a wider range of neighborhoods, and fund more than 200,000 new vouchers. Housing Choice Vouchers are highly effective at reducing homelessness, overcrowding, and housing instability, but due to insufficient funding, they and other ongoing federal rental assistance only help 1 in 4 eligible households.

Providing more vouchers is the most effective housing policy available to help people struggling to afford homes during the current surge in housing costs, since vouchers can deliver assistance promptly and are tightly targeted on those with the greatest need. At least 75 percent of vouchers must go to extremely low-income households, defined as those with incomes below the federal poverty line or 30 percent of the local median income, whichever is higher. The President’s proposal also would allow the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to require that some of the 200,000 new vouchers assist people experiencing or at risk of homelessness and survivors of domestic violence and human trafficking.

The budget also proposes increases in funding for homelessness programs and public housing. Its increase of $363 million above the 2022 enacted level for HUD’s Homeless Assistance Grants includes $134 million for new projects to address homelessness among youth and survivors of violence and trafficking while also renewing existing homeless programs. The budget also includes new investments to preserve the nation’s public housing developments and improve quality of life for their residents.

In addition to these increases in discretionary funding, the budget would provide $50 billion in mandatory funding and additional Low-Income Housing Tax Credits to increase housing supply. This includes $35 billion for a new program called the Housing Supply Fund, which would provide grants to develop housing for renters and homebuyers (including families with incomes of up to 150 percent of the area median who live in high-cost areas) and to support policies that remove barriers to the development of affordable housing. Some of the funding would be set aside for tribes.

However, further targeting of the funds and rental assistance is needed to ensure that the proposal meets the needs of households who most need help to afford housing. A large majority of renters who pay more than half of their income for rent and utilities have incomes below 30 percent of the local median. Housing developed with the Housing Supply Fund generally wouldn’t be affordable to people with incomes at that level unless coupled with a voucher or other rental assistance. Also, vouchers — unlike supply investments — allow families to live in a unit of their choice and to move without losing their housing assistance if they need to (for example to be near a job opportunity or a needed caregiver). That’s why any large-scale investment of mandatory funding for housing should include both supply investments like those the Administration has proposed and further expansion of the housing voucher program.

Improving Child Care and Education

Child care and pre-kindergarten. The President’s budget would increase discretionary funding for the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG), the main federal funding source of child care assistance, by $1.4 billion (23 percent) in 2023. [4] For Head Start, which funds local organizations (including nonprofits and school districts) to provide quality early childhood education for preschoolers in low-income households, the budget would increase funding by $1.2 billion (10.5 percent). While Head Start principally serves 3- and 4-year-olds, most of the increase would go to Early Head Start-Child Care partnerships to expand quality programming for infants and toddlers. The budget also would increase Preschool Development Grants, which support states in building out systems of early learning, by $160 million (55 percent).

Strengthening early childhood programs is critical to improving educational and employment outcomes for children in low-income families, to enabling parents, particularly mothers, to participate more fully in the economy, and to closing longstanding racial gaps in economic well-being resulting from racism and discrimination. Due to lack of funding, in 2019-2020 state-funded pre-K programs enrolled only 34 percent of 4-year-olds and 6 percent of 3-year-olds,[5] and only 1 in 7 eligible children receive child care assistance through CCDBG.[6] Because of the magnitude of the funding gaps and the long-term need, the early learning and care challenge should also be addressed in long-term economic legislation as the Administration has proposed. But the proposed increases in annual appropriations would achieve important advances.

Other budget provisions to improve outcomes for young children who are at risk for poor social, emotional, and educational outcomes include a proposed expansion of the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program to reach an additional 165,000 families, and increased funding for child welfare initiatives to keep families intact, reduce the use of foster care, and reduce the overrepresentation of children and families of color in the child welfare system.

K-12 education. The budget would more than double funding for Title I grants for education of disadvantaged students, from $17.5 billion in 2022 to $36.5 billion in 2023. Of that increase, $3 billion would come through increased discretionary appropriations and $16 billion from a proposed new mandatory funding stream (outside the appropriations process). Title I provides grants to school districts serving low-income communities to help them provide additional services and supports to students from low-income or disadvantaged backgrounds and narrow the resource gap between high-poverty schools and other schools.

In addition, the budget requests a $2.9 billion (22 percent) increase above 2022 for grants to states under Part B of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which help cover the cost of special education services for students with disabilities. The increased funding would better keep pace with the number of children receiving services and reverse declines in the share of special education costs that the federal grants cover. The budget also seeks a $244 million (29 percent) increase in grants to states for English language acquisition, to help students learning English attain proficiency and achieve academic success.

Higher education. The budget proposes a significant increase in Pell Grants, the main form of federal financial aid for undergraduate students from low- and middle-income families, which assist more than 6 million students. Pell Grants are funded from a combination of discretionary and mandatory funding. Low-income students were particularly likely to drop out of college or not enroll at all during the pandemic;[7] this substantial increase in the Pell Grant could help reverse that trend.

The budget also calls for an increase of about $800 million (27 percent) above 2022 for the Higher Education account, much of which focuses on improving equity and opportunity for students of color and students from low-income backgrounds. Programs receiving increases include support for Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities, and other Minority Serving Institutions to strengthen their academic programs, student services, and finances. Other increases within the account go to the TRIO programs, which promote college access and completion for underserved students, and GEAR UP, which helps low-income elementary and secondary students prepare for and pursue postsecondary education.

Strengthening, Expanding Health Coverage

Mental health and substance use. The President’s budget includes a suite of proposals to address the urgent need for behavioral health care (mental health and substance use treatment and recovery services), which has grown due to the pandemic.[8] While the ACA expanded access to behavioral health care, many people lack meaningful access to care despite having coverage, and those who are uninsured, including over 2 million people in states that haven’t expanded Medicaid, often have no access at all.[9]

The budget would strengthen Medicaid, the main federal funding source for community-based behavioral health care for people with low incomes,[10] including by helping states strengthen Medicaid mental health provider capacity and expanding and making permanent the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic demonstration program, which provides enhanced Medicaid funding to behavioral health clinics that meet robust services criteria.

The budget would also invest in behavioral health services in Medicare and the Veterans Affairs health system and require all health plans, including group employer plans, to provide behavioral health coverage. It would provide funding for the federal government and states to do more to enforce the existing rules requiring insurance plans that cover behavioral health care to achieve parity between coverage of physical health and behavioral health services. It also would provide funding to school systems to increase access to school counselors, nurses, and others who can attend to children’s mental health needs. And it would increase key behavioral health grant programs such as the Community Mental Health Services and Substance Use Prevention and Treatment Block Grants, and provide funding to implement the 9-8-8 mental health crisis and suicide prevention hotline (which will go live in July) and invest in other suicide prevention efforts.

Public health and pandemic preparedness. The budget proposes $81.7 billion in mandatory funding, available over five years, to strengthen the nation’s capacity to prepare for and respond to future pandemics or other serious biological threats. These funds would be spread among several agencies at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) would receive $28 billion to enhance domestic and global disease surveillance, expand laboratory capacity, and strengthen the public health workforce and data systems. The National Institutes of Health would receive $12 billion for research and development of vaccines, diagnostics, and therapeutics and to expand laboratory and clinical trial capacity. The Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response would receive $40 billion to support advanced research and development of vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics for high-priority threats and to scale up domestic manufacturing capacity.

The budget also calls for increases in regular annual appropriations for key HHS agencies, such as a $2.1 billion (28 percent) increase for CDC and a $130 million (15 percent) increase for the Strategic National Stockpile of drugs and other medical supplies for rapid response to health emergencies.

Tribal programs. To strengthen the nation-to-nation relationship between the federal government and Tribal Nations, the budget would increase the Indian Health Services (IHS) budget by $2.5 billion (37 percent) over the 2022 level. This would enable the IHS to keep pace with increases in health care costs and population and make needed updates to facilities and IT. The increase would also represent a down payment on rectifying the historical underfunding of the agency and addressing the stark health disparities that American Indian and Alaskan Native people face. The budget would also shift IHS funding from discretionary to mandatory and raise funding by nearly 300 percent by the tenth year.

In addition, the budget proposes a $1.1 billion increase over 2022 in annual appropriations for the Department of the Interior’s Indian Affairs programs. Programs receiving increases include those that work on public safety and justice, land consolidation, tribal climate adaptation, postsecondary education (Tribal Colleges and Universities), and self-determination strengthening, among others.

Improving Governance

Several proposals in the President’s budget aim to improve the delivery of federal services.

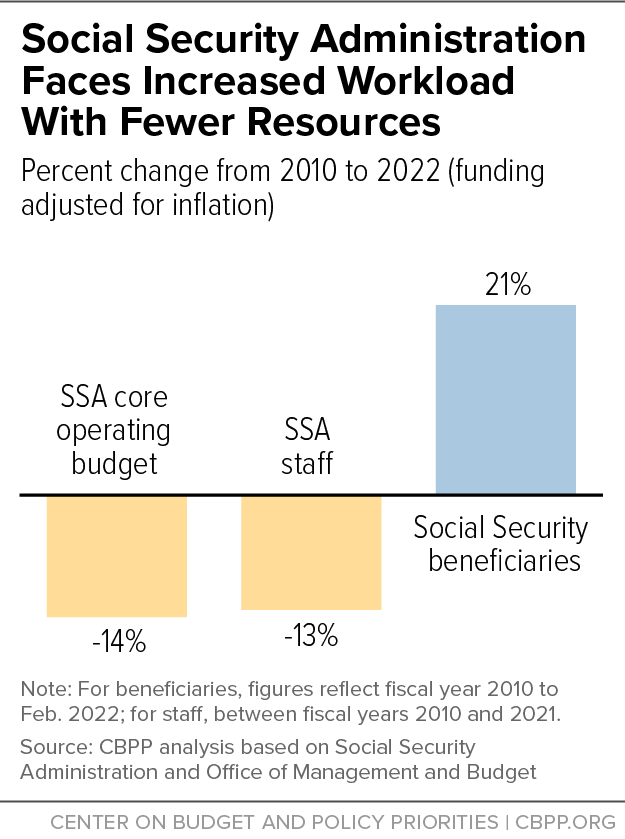

SSA. The budget includes a $1.4 billion (12 percent) increase in the Social Security Administration (SSA) operating budget, a long-overdue corrective to more than a decade of austerity in which SSA’s operating budget fell by 14 percent since 2010, after inflation. Due to declining funding, SSA has 8,600 (13 percent) fewer staff than in 2010 even though the number of beneficiaries has risen by over 11 million since then. (See Figure 2.) This leaves fewer people to answer phones, take appointments, process applications, and answer questions. Though SSA has expanded its online and telephone self-service, much of the agency’s work requires trained staff to complete.

Nearly half of calls to SSA go unanswered because callers hang up when the wait is too long or they get busy signals.[11] Only about one-third of the estimated 180,000 children who had a parent die of COVID-19 have begun receiving Social Security survivor benefits. And the average wait for a disability determination has nearly doubled, from about three and a half months in 2010 to six months in 2022. SSA needs to staff up as its field offices reopen to contend with backlogs that grew during the pandemic, when the closing of field offices plus recent problems with telephone service combined to make accessing benefits more difficult. Without a significant boost in funding, SSA will face further staff attrition and even longer wait times and backlogs.

IRS. The budget proposes to increase Internal Revenue Service (IRS) appropriations by 12 percent over the 2022 level, including increases of $605 million for customer service funding and $424 million for enforcement and a total of $310 million to help overhaul the IRS’ outdated technology systems, which date back to the 1960s. The increases would significantly help the agency as it begins rebuilding after a decade of damaging funding cuts that have undermined the agency’s capacity to fulfill its core responsibilities of helping taxpayers navigate the tax system and enforcing the nation’s tax laws. Overall inflation-adjusted IRS funding is down by more than one-sixth since 2010, and the IRS’ computer systems have become increasingly outdated. While considerably more would be needed to even return funding to 2010 levels after adjusting for inflation, the President’s budget would make important progress toward the ultimate goal of a rebuilt IRS that restores public trust in the fairness of the tax system. See below for additional discussion of the President’s complementary long-term funding proposal for the IRS.

Revenue-Raising Proposals

Over the past two decades, regressive tax cuts have suppressed revenues and widened inequality while failing to deliver on the promise of economic growth their supporters promised. They have also hampered the nation’s ability to put in place policies that help families and children thrive and promote economic security and broadly shared growth. The President’s budget would bolster the revenue system and move toward ending this damaging policy of underinvestment.

The budget builds on the provisions in the House-passed Build Back Better package but does not include those House provisions because they are part of the ongoing discussions around an economic package (and so are considered part of the deficit-neutral reserve fund, noted above). The budget does include a number of specific revenue policies, proposing new policies as well as some that were in the previous Biden budget but are not part of the ongoing discussions. Together, these provisions raise enough revenue to more than offset the cost of the budget’s proposed funding increases and investments, reducing the deficit over the next decade by more than $1 trillion.

Revenue Proposals in House Package

The House-passed package would raise a reported $1.85 trillion over ten years in three main ways: requiring people with high incomes to pay a fairer amount of tax, reducing unwarranted tax advantages for profitable corporations (particularly large multinationals), and improving enforcement of the nation’s tax laws to reduce the roughly $600 billion annual gap between taxes legally owed and taxes paid — a gap disproportionately due to high-income filers’ noncompliance with the law.

High-income individuals. Much of the annual income of very high-income households doesn’t appear on their annual tax returns because it is in the form of unrealized capital gains. And the part of their income that is taxed on an annual basis often benefits from special tax breaks or discounted rates. Changes in tax policy since the late 1990s have expanded these advantages, particularly tax cuts in the George W. Bush and Donald Trump administrations. Several provisions of the House-passed package would reduce these tax advantages, including:

- Surtax on multi-millionaires. The package imposed a new 5 percent surtax on households with adjusted gross income (AGI) above $10 million and an additional 3 percent tax on those with AGI above $25 million. The tax would apply to both labor earnings and capital income.[12]

- Closing net investment income loophole. High-income people pay a 3.8 percent Medicare tax on their wages and self-employment income. In 2010, Congress enacted a parallel 3.8 percent tax on high-income people’s net investment income. However, some income of high-income people who own pass-through businesses (including partnerships and S corporations) doesn’t face this tax.[13] The House-passed package closed this loophole for those with incomes of more than $400,000.

Large corporations. More than 130 countries representing more than 90 percent of the world’s economy agreed in October 2021 to enact major international tax reforms aimed at thwarting the shifting of corporate profits to low-tax countries and ending the “race to the bottom,” in which countries cut their corporate taxes to encourage companies to locate within their borders.[14] The agreement includes a 15 percent global minimum tax on companies’ foreign profits. Certain features of this minimum tax are stronger than the existing U.S. minimum corporate tax on multinationals’ foreign profits. The House-passed package included several provisions to align the U.S. more closely with the deal, such as raising the tax rate on foreign profits to 15 percent (from 10.5 percent) and requiring corporations to calculate the minimum tax in each country in which they operate instead of an aggregate global basis.

The package would also ensure that large, profitable corporations pay at least some tax on their domestic profits by imposing a 15 percent minimum tax on the financial statement (or “book”) income they report to shareholders, which may better represent a company’s true economic position than taxable income. This would largely prevent large corporations from reporting profits to shareholders while paying no corporate taxes.

Tax enforcement. Funding cuts since 2010 have severely weakened the IRS’ ability to enforce the nation’s tax laws. For example, the number of IRS revenue agents — auditors uniquely qualified to process the complex returns of high-income individuals and businesses, which are disproportionately responsible for the $600 billion annual tax gap — has fallen by 39 percent since 2010. The House package provided the IRS with $80 billion over the next decade so it can rebuild its audit staff and make long-term commitments to technology upgrades. The proposed increases in IRS discretionary funding in the President’s 2023 budget, discussed above, would be in addition to this new mandatory funding.

Revenue Proposals in 2023 Budget

The President’s 2023 budget includes several policies that were in the President’s 2022 budget but are not part of current legislative discussions, including increases in the corporate tax rate and in individual tax rates for high-income households. It also includes new proposals, including one to ensure that the wealthiest households who have gained the most from the nation’s economy pay at least a minimum level of tax. Together, these proposals would raise roughly $2.5 trillion over the next ten years.[15]

High-income households: top rates. A major reason why many wealthy households pay a relatively small share of their income in taxes is that capital and certain business income — which make up most of wealthy households’ incomes — are taxed at a far lower rate than wage income. Moreover, the top ordinary income tax rate of 37 percent, which applies to interest and stock options as well as wages and salaries, is well below the post-World War II average of 59 percent.[16]

The President’s budget would return the top marginal income tax rate to the rate before the 2017 tax law, 39.6 percent, and set the rate on capital gains and dividends at the same 39.6 percent for households with annual incomes over $1 million. It also would eliminate the loophole for “carried interest” — the share of a private equity fund’s profits that a fund manager can receive as compensation, which is now taxed at the capital gains rate instead of the higher rates for wages and salaries.

High-income households: minimum tax on the wealthiest. A new proposal in the budget would ensure that households with more than $100 million in wealth pay at least 20 percent of their annual income in individual income tax.

The individual income tax — the largest federal tax, raising roughly half of federal revenue — is based on ability to pay, meaning that a person’s effective tax rate (the share of their annual income they owe in tax) should rise as their income rises. For most of the income spectrum it generally works that way; for example, someone whose annual salary is $1 million will pay income taxes at a higher effective rate than someone whose salary is $50,000. But this relationship breaks down at the very top because unrealized capital gains, the primary source of annual income for many of the richest people in the country, are not taxed on an annual basis. Instead, they are taxed only when the asset is sold, and if the asset is never sold during the asset holder’s lifetime, the income tax that would be owed on all previously accrued gain is simply erased, so wealthy households can avoid income tax on this income potentially forever.

The President’s budget would address this fundamental unfairness by requiring taxpayers with more than $100 million in wealth to pay at least 20 percent of their income, including their unrealized capital gains, in tax each year. The wealthiest people thus would pay a minimum amount of income taxes each year on their main source of income, just as millions of wage and salary earners already do.

The proposal includes mechanisms to address various implementation issues that some commentators have raised about earlier similar proposals. For example, it would allow filers to spread their minimum tax payments over several years, enabling them to smooth the yearly changes in the amount of their investment income.[17]

Large corporations. The budget proposes to raise the corporate income tax rate from 21 percent to 28 percent, still significantly below the 35 percent rate in effect before the 2017 tax law. The increase would fall mostly on corporate shareholders, who reaped most of the benefit of the 2017 corporate tax cut. The ownership of corporate shares — as with other kinds of wealth — is highly concentrated at the top. Foreign investors own about 40 percent of U.S. corporate equity, while retirement accounts own about 30 percent and investors with taxable accounts about 25 percent.[18] Within the latter two categories, wealthy households directly or indirectly own the vast majority of corporate stock.[19]

Closing loopholes. The President’s budget would limit the use of certain longstanding loopholes that allow wealthy people to defer or avoid tax. For example, it would limit estate and gift tax avoidance using certain types of trusts such as “grantor retained annuity trusts” (GRATs), which wealthy people can use to shelter massive sums from the estate tax.[20]

The budget would also sharply limit the “like-kind exchange” loophole, which allows people to sell certain types of assets and still avoid paying tax on the realized capital gain in the year of the sale. The 2017 tax law eliminated like-kind exchanges for certain assets but retained them for real estate, so wealthy real estate investors can continue to sell buildings without claiming the gains from those sales on their income tax returns. The budget would repeal like-kind exchanges if the gain exceeds $500,000 ($1 million for married filers).

End Notes

[1] All years discussed in this paper are federal fiscal years unless noted otherwise.

[2] The President’s budget also includes defense proposals and proposals for non-defense programs beyond those discussed in this analysis.

[3] These estimates use the standard CBPP methodology for analyzing discretionary appropriations. They reflect overall funding for non-defense appropriations, including program integrity and other programs typically funded outside of the Appropriations committees’ topline, and excluding the savings from changes in mandatory programs (CHIMPs) and mortgage insurance premiums as well as emergency and disaster relief appropriations. The resulting non-defense totals are $820 billion for the 2023 budget proposal and $723 billion for the 2022 enacted level.

[4] Federal child care funding also has a mandatory component, which the budget would hold flat at $3.55 billion.

[5] Allison H. Friedman-Krauss et al., “The State of Preschool 2020,” National Institute for Early Education Research, 2021, https://nieer.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/YB2020_Executive_Summary_080521.pdf.

[6] Administration for Children & Families, “ACF Releases Guidance on Supplemental Child Care Funds in the American Rescue Plan,” June 11, 2021, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/media/press/2021/acf-releases-guidance-supplemental-child-care-funds-american-rescue-plan.

[7] Heather Long and Danielle Douglas Gabriel, “The latest crisis: Low-income students are dropping out of college this fall in alarming numbers,” Washington Post, September 16, 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/09/16/college-enrollment-down/.

[8] Jennifer Sullivan, Miriam Pearsall, and Anna Bailey, “To Improve Behavioral Health, Start by Closing the Medicaid Coverage Gap,” CBPP, October 4, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/to-improve-behavioral-health-start-by-closing-the-medicaid-coverage-gap.

[9] The Affordable Care Act requires states to include mental health and substance use treatment as a covered benefit for people eligible under Medicaid expansion. Health coverage plans offered through the Affordable Care Act’s marketplace must cover behavioral health services that are comparable to the plan’s physical health coverage, thereby providing access to coverage for substance use disorder treatment.

[10] Anna Bailey et al., “Medicaid Is Key to Building a System of Comprehensive Substance Use Care for Low-Income People,” CBPP, March 18, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/medicaid-is-key-to-building-a-system-of-comprehensive-substance-use-care-for-low.

[11] Social Security Administration, “The Social Security Administration’s Telephone Service Performance,” November 2021, https://oig.ssa.gov/assets/uploads/A-05-20-50999Summary.pdf.

[12] More specifically, the surtax applies to “modified AGI,” which differs from AGI in minor respects.

[13] Chuck Marr, “Why Closing the S Corporation Loophole Is a Good Move,” CBPP, June 16, 2010, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/why-closing-the-s-corporation-loophole-is-a-good-move.

[14] OECD, “Statement on a Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy — 8 October 2021,”

https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/statement-on-a-two-pillar-solution-to-address-the-tax-challenges-arising-from-the-digitalisation-of-the-economy-october-2021.htm.

[15] The budget does not make any specific assumptions about the 2017 tax law provisions that are scheduled to expire after 2025, except for its proposal to raise the top income tax rate. As a result, the budget effectively assumes that the other expiring policies will end as scheduled or the cost of their extension will be offset.

[16] Tax Policy Center, “Historical Highest Marginal Income Tax Rates,” January 18, 2019, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/statistics/historical-highest-marginal-income-tax-rates.

[17] Jason Furman, “Biden’s Better Plan to Tax the Rich,” Wall Street Journal, March 28, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/bidens-better-plan-to-tax-the-rich-unrealized-capital-gains-assets-treasury-distortion-11648497984?mod=hp_opin_pos_5.

[18] Steve Rosenthal and Theo Burke, “Who’s Left to Tax? US Taxation of Corporations and Their Shareholders,” New York University School of Law, October 27, 2020, https://www.law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/Who%E2%80%99s%20Left%20to%20Tax%3F%20US%20Taxation%20of%20Corporations%20and%20Their%20Shareholders-%20Rosenthal%20and%20Burke.pdf.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Bloomberg, “How to Preserve a Family Fortune Through Tax Tricks,” September 12, 2013, https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/infographics/how-to-preserve-a-family-fortune-through-tax-tricks.html.

More from the Authors