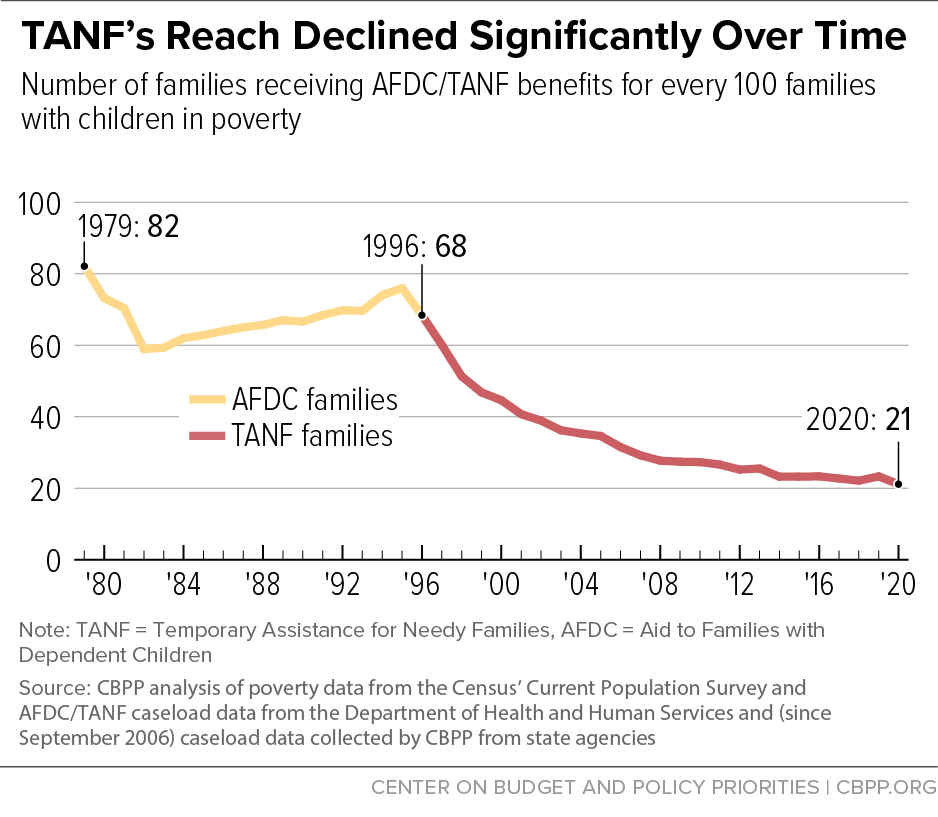

The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant is designed to provide temporary cash assistance to families in poverty — primarily those with no other means to meet basic needs — but its reach has shrunk considerably over time.[1] In 2020, for every 100 families in poverty, only 21 received cash assistance from TANF, down from 68 families when TANF was first enacted in 1996. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic crisis — a precarious time for families — this “TANF-to-poverty ratio” (TPR) is the lowest in the program’s history. (See Figure 1.) If TANF had maintained the same reach to families in poverty as its predecessor, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), had in 1996, 3.44 million families would have received TANF in 2020, about 2.38 million more than reported for that year.[2]

Our analysis finds that:

- TANF provides temporary cash assistance to few poor families and its reach continues to shrink, both nationally and in nearly every state. Though TANF caseloads grew in many states in 2020, the program’s benefit levels are extremely low in many states, falling far short of what families need to meet their basic needs.[3]

- A history of racist policies that limited Black mothers’ access to family cash assistance programs continues to contribute to racial disparities in access to TANF today. Nationally, Black children are less likely than white children and somewhat less likely than Latino children to have access to TANF assistance when their families fall into crisis.[4]

- TANF lifts far fewer families out of deep poverty (that is, incomes below half of the poverty line) than AFDC and has put poor children at risk of much greater hardship. Research shows that even relatively small amounts of additional family income make a difference to children’s well-being, now and in the future.

TANF is overdue for significant permanent improvements. The states and the federal government have a critical role in ensuring that families with the lowest incomes have access to a minimum level of support to meet their basic needs. The TANF block grant shifted that responsibility to states, which — with no national standards to hold them accountable for providing assistance to families in need — acted in their own self-interest, not in the best interest of families in poverty and particularly of families of color. State and federal policy changes should focus on serving more families who need assistance, alleviating the program’s deep racial disparities, and ensuring that adequate resources are available to achieve these goals.

Amid the nationwide hardship that resulted from the pandemic in 2020, the number of families receiving TANF benefits increased in some states but stayed the same or fell in others over the course of the year. Nationally, the average monthly TANF caseload declined between 2019 and 2020, but that metric misses the rise and fall of the caseload during the year. In fact, caseloads rose at the beginning of the pandemic in early 2020 and fell by the end of the year. Some of this decline likely is attributed to the availability of pandemic federal unemployment benefits and other financial assistance, such as Economic Impact Payments.

Before 2020, the TPR declined because TANF caseloads had fallen much more than the number of families experiencing poverty. In 2020, the TPR declined because the average monthly TANF caseload fell while the number of families in poverty increased.

The national TANF-to-poverty ratio misses the extreme — and growing — variation among the states. In 2020 the TPR ranged from 71 in California and Vermont to just 4 in Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas.[5] (See Table 1.) The TPR fell in most states between 2006 (the last time TANF was reauthorized) and 2020 for several reasons: state responses to federal policy changes when TANF was reauthorized and in response to the pandemic, adoption of more restrictive policies as part of a broader attack on economic security programs, and policy changes to restrict access and reduce costs during the Great Recession of 2007-2009, among other factors. The TPR dropped by 10 or more points in 25 states over this period; in 14 of those states, it dropped by 20 points or more.

An especially troubling trend is the number of states with TPRs of 10 or less. In 2006, only three states (Idaho, Louisiana, and Wyoming) had such low ratios. The list grew during the Great Recession and has continued growing since then. In 2020, 14 states — Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, and Wyoming — had TPRs of 10 or less.

A history of racist policies that aimed to limit Black mothers’ access to family cash assistance programs, from strict work requirements and time limits to invasive behavioral requirements, continues to contribute to racial disparities in access to TANF today.

Forty-one percent of the nation’s Black children live in states with TPRs of 10 or less, compared to 33 percent of Latino children and only 28 percent of white children.[6] Nationally, therefore, Black children are less likely than white children and somewhat less likely than Latino children to have access to TANF assistance when their families fall into crisis.

Moreover, if Black families do manage to receive TANF cash benefits, they are likelier to live in states with the lowest benefit levels, which do little to help families meet their basic needs.[7] And research finds that all else equal, states with larger African American populations have less generous and more restrictive TANF policies.[8] These policies impact everyone, regardless of race: today, states that historically denied Black families have simply opted to help few families at all.[9]

The decline in access to TANF benefits has left many of the families experiencing the deepest poverty without resources to meet their basic needs. TANF does far worse than AFDC in reaching families, particularly those with children and those in deep poverty. TANF benefits are not sufficient to lift families out of poverty in any state, and while AFDC lifted more than 2.9 million children out of deep poverty in 1995, by 2020, most states had more families living in deep poverty than receiving TANF.[10]

The evidence is clear that when families have more income, children do better in the future. Even relatively small amounts of income make a difference. Among families with incomes below $25,000, children whose families received a $3,000 annual income boost when the children were under age 6 earned 17 percent more as adults and worked 135 more hours per year after age 25 than otherwise-similar children whose families didn’t receive the income boost, research finds.[11] That research suggests that TANF policy changes that cut families’ income, such as harsher sanctions or shorter time limits or significantly reduced benefits, could harm young children now and in the future. More recently, a major study found that cash assistance directly improves infant brain development associated with higher language, cognitive scores, and better social skills.[12]

TANF is overdue for significant improvements. State and federal policy changes should focus on serving more families who need assistance, alleviating the program’s deep racial disparities, and ensuring that adequate resources are available to achieve these goals. For example, states should lift income thresholds and asset tests, remove barriers to access, and stop cutting off families who are still struggling. Additionally, federal policymakers should hold states accountable for serving families in need, require states to direct a specific share of TANF resources to families receiving cash assistance, and increase the block grant and index it to inflation.