Extracting Lessons for State Finances

What Other States Should Learn from Energy-Producing States’ Revenue Woes

End Notes

[1] National Association of State Budget Officers, “Fiscal Survey of the States,” Fall 2016, http://www.nasbo.org/reports-data/fiscal-survey-of-states

[2] For example, Massachusetts is projecting an $800 million [?] budget gap for fiscal year 2018; Nebraska and Virginia are facing large gaps ($870 million and $1.5 billion, respectively) in their upcoming two-year budgets.

[3] Elizabeth C. McNichol, “Strategies to Address the State Tax Volatility Problem,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 18, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/strategies-to-address-the-state-tax-volatility-problem.

[4] Devashree Saha and Mark Muro, “Permanent Trust Funds: Funding Economic Change with Fracking Revenues,” Metropolitan Policy Program at Brookings, April 2016, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Permanent-Trust-Funds-Saha-Muro-418-1.pdf.

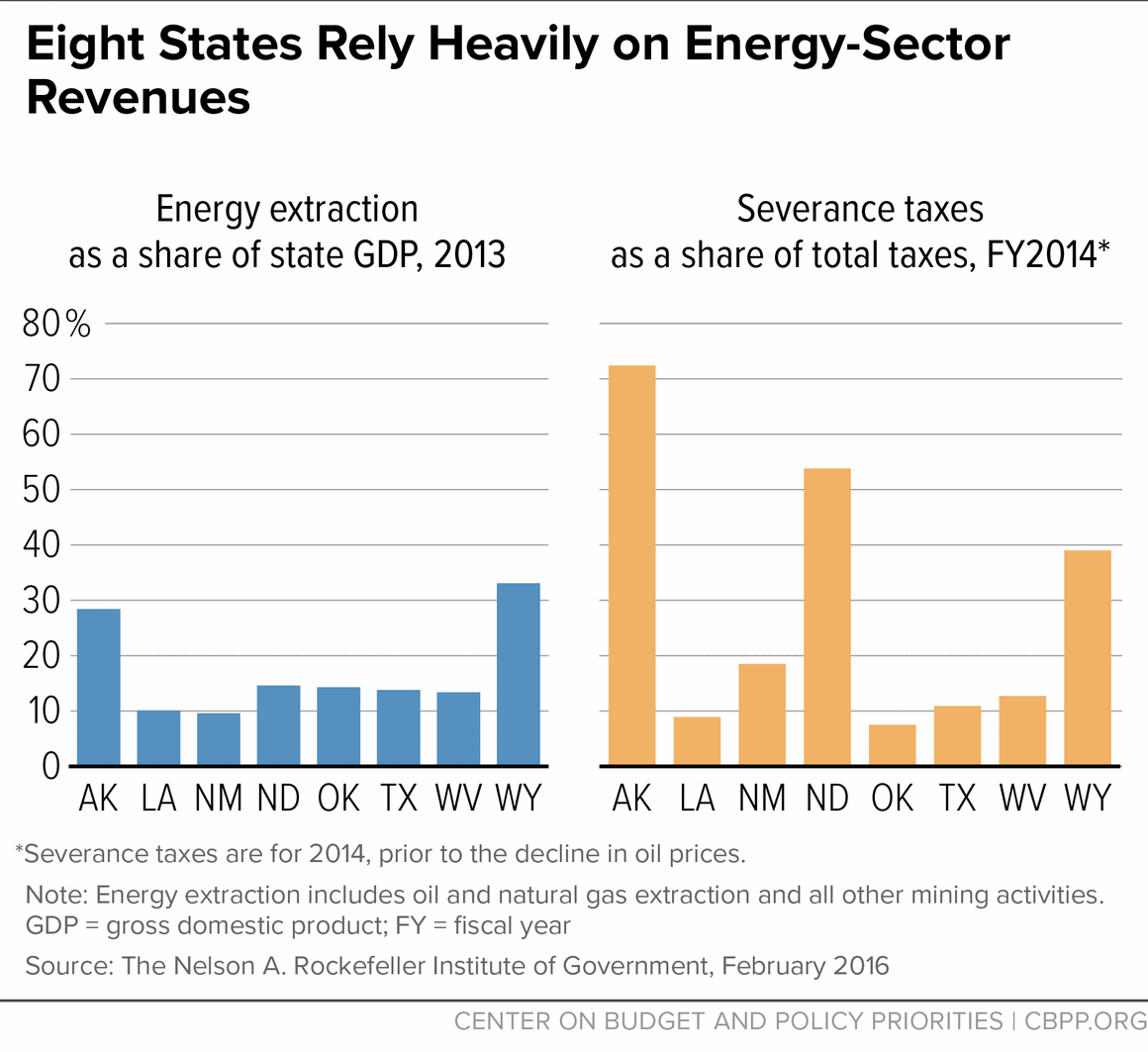

[5] Alaska’s revenue was particularly hard hit by the decline in oil prices. By fiscal year 2015, severance taxes made up just 12 percent of tax revenues. (CBPP calculations of Census Government Finance data.) Fiscal year 2017 total general fund revenue was just 16 percent of the average for fiscal years2003–2013, Alaska Revenue and Expenditures FY07-FY17, Legislative Finance Division Informational Paper 17-1, July 2016.

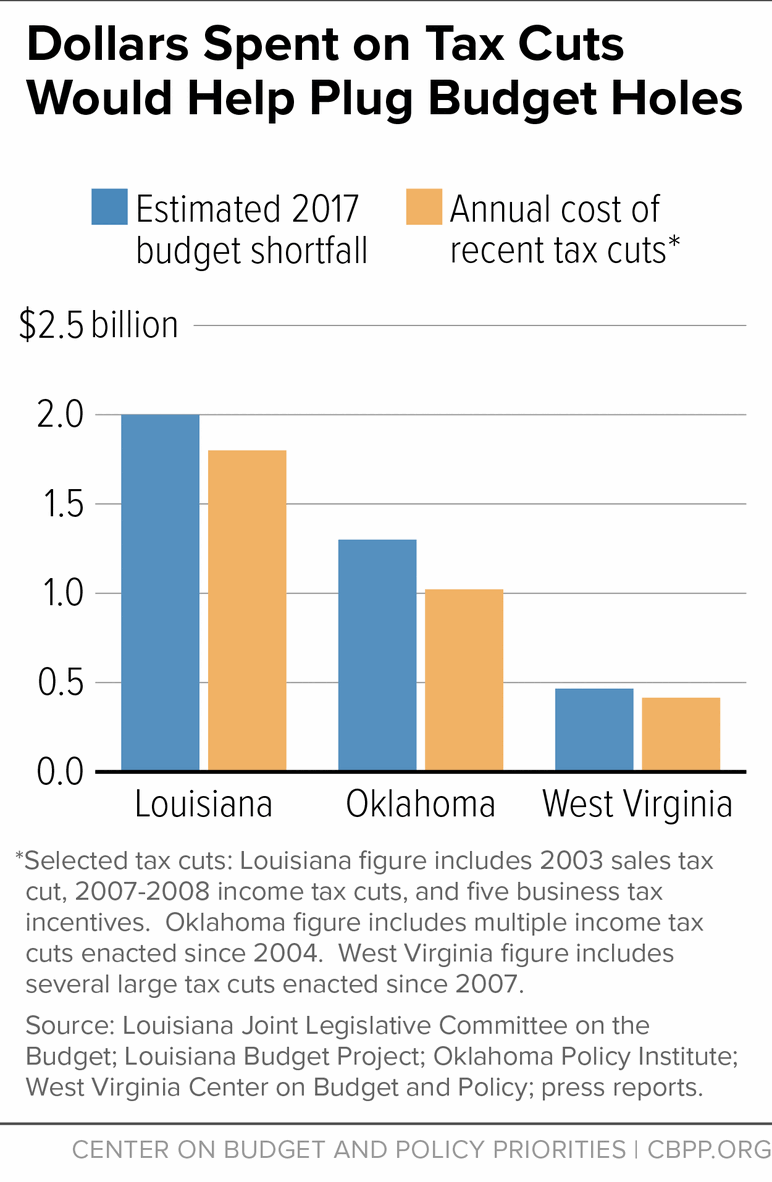

[6] Louisiana Joint Legislative Committee on the Budget, “Executive Budget Presentation, Fiscal Year 2016-2017,” February 13, 2016, http://www.doa.la.gov/comm/presentations/JLCB%20Exec%20Budget%20Presentation%202-13-16.pdf.

[7] Associate Press, “See which Louisiana taxes are going up, and which aren’t,” The Times-Picayune, March 10, 2016, http://www.nola.com/politics/index.ssf/2016/03/see_how_louisiana_taxes_are_go.html; Julia O’Donoghue, “Louisiana House committee approves budget that funds TOPS, but not hospitals,” The Times-Picayune, May 10, 2016, http://www.nola.com/politics/index.ssf/2016/05/louisiana_house_budget_restore.html#incart_article_small.

[8] Michael Mitchell, Michael Leachman, and Kathleen Masterson, “Funding Down, Tuition Up,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 15, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/funding-down-tuition-up.

[9] Elizabeth Crisp, “State revenue forecasting panel delays action on deficit until January,” The Advocate, December 13, 2016, http://www.theadvocate.com/baton_rouge/news/politics/article_8d72428c-c15a-11e6-9d6d-fbb5b68df450.html?sr_source=lift_amplify.

[10] Elizabeth Crisp, “Thousands of students could lose TOPS scholarship under latest ‘very nasty’ proposed budget cuts,” The Advocate, April 16, 2016, http://theadvocate.com/news/15467310-77/gov-john-bel-edwards-presents-750m-budget-cut-plan.

[11] Kevin Litten, “DHH secretary blasts Appropriations for ‘faux,’ ‘nonsensical’ budget proposal,” The Times-Picayune, May 12, 2016, http://www.nola.com/politics/index.ssf/2016/05/dhh_budget_cuts_hospitals.html.

[12] Julia O’Donoghue, “Louisiana’s budget is a hot mess: How we got here,” The Times-Picayune, February 19, 2016, http://www.nola.com/politics/index.ssf/2016/02/louisiana_is_in_a_budget_mess.html. The Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy has estimated the annual impact to be just slightly higher, but in the same ballpark.

[13] Steve Spires, “Louisiana’s $1.6 billion problem: How did we get here?” Louisiana Budget Project, February 24, 2016, http://www.labudget.org/lbp/2015/02/louisianas-1-6-billion-problem-how-did-we-get-here/.

[14] Louisiana Legislative Auditor, “Severance Tax Suspension for Horizontal Wells,” August 19, 2015, https://app.lla.state.la.us/PublicReports.nsf/65C7443D8D09105F86257EA6007174D9/$FILE/00009E0B.pdf; Louisiana Department of Revenue, “Tax Exemption Budget 2015-2016,” January 2016, http://revenue.louisiana.gov/Publications/TEB(2015-2016).pdf.

[15] Oklahoma Office of Management & Enterprise Services, “BOE approves $5.8B for appropriations, FY 2017 Budget Hole Projected at $1.3B,” February 16, 2016, http://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/OKOMES/bulletins/136b6c9; Oklahoma Policy Institute, “Budget Trends and Outlook – March 2016,” March 4, 2016, http://okpolicy.org/budget-trends-and-outlook-march-2016/.

[16] Oklahoma Policy Institute, “FY 2017 Budget Highlights,” June 7, 2016, http://okpolicy.org/fy-2017-budget-highlights/.

[17] Chuck Marr, et al., “EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated October 1, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/eitc-and-child-tax-credit-promote-work-reduce-poverty-and-support-childrens?fa=view&id=3793.

[18] Barbara Hoberock, “With state facing $868 million budget hole, revenue will fall short of triggering income tax reduction,” Tulsa World, December 21, 2016, http://www.tulsaworld.com/news/capitol_report/with-state-facing-million-budget-hole-revenue-will-fall-short/article_cd4fb785-9f61-578f-859c-5ea9fc422fe0.html.

[19] Oklahoma Health Care Authority, “Press Release: OHCA to Propose Provider Rate Cuts,” March 29, 2016, http://www.okhca.org/about.aspx?id=18904.

[20] David Blatt, “The Cost of Tax Cuts in Oklahoma,” Oklahoma Policy Institute, January 12, 2016, http://okpolicy.org/the-cost-of-tax-cuts-in-oklahoma.

[21] David Blatt, “Even amid energy bust, Oklahoma’s oil and gas tax breaks exceed $400 million per year,” Oklahoma Policy Institute, May 5, 2016, http://okpolicy.org/even-amid-energy-bust-oklahomas-oil-gas-tax-breaks-exceed-400-million-per-year/.

[22] Ted Boettner and Sean O’Leary, “Confronting the Fiscal Gap,” West Virginia Center on Budget & Policy, February 16, 2016, http://www.wvpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/PDF-FY17-Gov-Budget-Brief-2.16.16-FINAL.pdf; Phil Kabler, “Report says tax cuts responsible for budget deficit,” Charleston Gazette-Mail, February 16, 2016, http://www.wvgazettemail.com/news/20160216/report-says-tax-cuts-responsible-for-budget-deficit; State News Service, “Governor Tomblin Issues Statement on Budget Following New Revenue Estimates for Fiscal Year 2017,” HighBeam Research, March 15, 2016. [link?]

[23] Phil Kabler, “WV agencies: Hypothetical budget cut could force layoffs, closures,” Charleston Gazette-Mail, February 18, 2016, http://www.wvgazettemail.com/news/20160218/wv-agencies-hypothetical-budget-cut-could-force-layoffs-closures and Mitchell, Leachman, and Masterson.

[24] Boettner and O’Leary.

[25] Michael Leachman, et al., “State Personal Income Tax Cuts: Still A Poor Strategy for Economic Growth,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated May 14, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-personal-income-tax-cuts-still-a-poor-strategy-for-economic and Michael Mazerov, “Academic Research Lacks Consensus on the Impact of State Tax Cuts on Economic Growth,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 17, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=3975.

[26] Erica Williams, “A Fiscal Policy Agenda for Stronger State Economies,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 13, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/a-fiscal-policy-agenda-for-stronger-state-economies.

[27] Elizabeth McNichol, “When and How States Should Strengthen their Rainy Day Funds,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 17, 2014, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/when-and-how-states-should-strengthen-their-rainy-day-funds?fa=view&id=4129.

[28] Elizabeth McNichol and Kwame Boadi, “Why and How States Should Strengthen Their Rainy Day Funds,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 3, 2011, https://www.cbpp.org/research/why-and-how-states-should-strengthen-their-rainy-day-funds?fa=view&id=3387.

[29] North Dakota Office of Management and Budget, “North Dakota Rev-E-News,” February 2016, https://www.nd.gov/omb/sites/omb/files/documents/newsletters/201602news.pdf.

[30] Office of Management and Budget, “Legislative Appropriations 2015-2017 Biennium,” https://www.nd.gov/omb/sites/omb/files/documents/agency/financial/state-budgets/docs/budget/appropbook2015-17.pdf?ts=2016021812.

[31] McNichol, 2014.

[32] Alaska Office of Management & Budget, “Ten Minute Fiscal Overview Presentation,” 2015, http://gov.alaska.gov/Walker_media/documents/sustainable-alaska/10-min-fiscal-overview.pdf.

[33] Office of Management and Budget, “FY2017 10-Year Plan,” January 22, 2016, https://www.omb.alaska.gov/ombfiles/17_budget/PDFs/FY2017_10-year_plan_1_22_2016_FINAL.pdf.

[34] Becky Bohrer, “With deadline looming, a look at Alaska budget proposals,” Newsminer, May 12, 2016, http://www.newsminer.com/news/alaska_news/with-deadline-looming-a-look-at-alaska-budget-proposals/article_5963eef2-18a2-11e6-9ded-bb65d06bd838.html; Kirk Johnson, “Alaska’s Schools Face Cuts at Every Level Over Oil Collapse,” The New York Times, March 14, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/15/us/oil-collapse-drains-alaskas-wide-ranging-education-system.html?_r=0; Ed Schoenfeld, “Budget cuts could leave communities without health care,” Alaska Public Media, April 18, 2016, http://www.alaskapublic.org/2016/04/18/budget-cuts-could-leave-communities-without-health-care/; Rashah McChesney, “Budget Cuts Affect Alaska’s Food Safety Division,” Claims Journal, May 12, 2016, http://www.claimsjournal.com/news/west/2016/05/12/270747.htm .

[35] Aidan Russell Davis, Carl Davis, and Matthew Gardner, “Distributional Analyses of Revenue Options for Alaska,” Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy, April 2016, http://itep.org/itep_reports/pdf/AKrevenueoptions0416.pdf.

[36] Wyoming Legislative Service Office, “2017 Budget Fiscal Data Book,” December 2016, http://legisweb.state.wy.us/budget/2017databook.pdf.

[37] Wyoming Joint Education Committee, “Wyoming K-12 Education Funding Deficit White Paper,” December 28, 2016, http://legisweb.state.wy.us/lsoweb/WhitePaperEducation.pdf.

[38] Higher volatility does not automatically bring higher long-term growth for all state taxes. For example, the corporate income tax is more volatile than the personal income tax but also grows more slowly over the long term. See, for example, R. Alison Felix, “The Growth and Volatility of State Tax Revenue Sources in the Tenth District,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Review, Third Quarter 2008, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/de6d/eeb4831daf425c2516ca352048005c9ba5b1.pdf.