- Home

- Expiration Of TANF Supplemental Grants A...

Expiration of TANF Supplemental Grants a Further Sign of Weakening Federal Support for Welfare Reform

LaDonna Pavetti, Ph.D., Liz Schott and Ife Finch

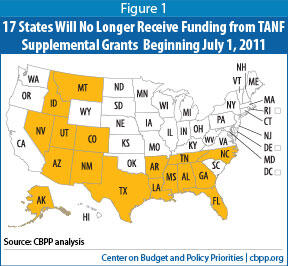

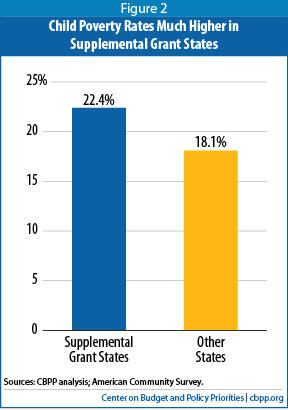

In a continued unraveling of the deal that Congress made with the states in enacting the 1996 welfare reform law, federal Supplemental Grants provided every year since 1996 to 17 states to augment their Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant will expire on July 1 (see Figure 1). These states include some of the poorest in the nation, with child poverty rates averaging 22 percent (see Figure 2). Several have also been hit especially hard by the economic downturn; nine have unemployment rates above the national average of 9.1 percent.

Allowing the Supplemental Grants to expire violates the spirit and substance of the 1996 welfare reform deal that Congress made with the states. Under the old Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) structure that the 1996 welfare law replaced, federal funding to states rose automatically when need increased in hard economic times and more families qualified for aid. The TANF block grant that replaced AFDC provides a flat amount of federal funding that does not rise when need increases, or when the cost of living increases due to inflation or when a state’s population (and in particular, its number of poor children) increase.

Neither of these additional funding streams will be available to states for the rest of fiscal year 2011 . The TANF Contingency Fund, designed to give states additional funding during downturns, was exhausted in December 2010. The Supplemental Grants are now expiring as well. In addition, the temporary TANF Emergency Fund, created by the 2009 Recovery Act to perform a similar function, expired on September 30, 2010.

For the first time in TANF’s history, Congress is now providing no additional TANF funding to help states respond to the increase in need stemming from an economic downturn or to address the inequities resulting from the funding formula of the TANF block grant. And, for the first time since AFDC’s creation in the 1930s, the federal government is offering no additional funding to states to help cover the increased need for AFDC- or TANF-funded help to poor families resulting from an economic downturn.

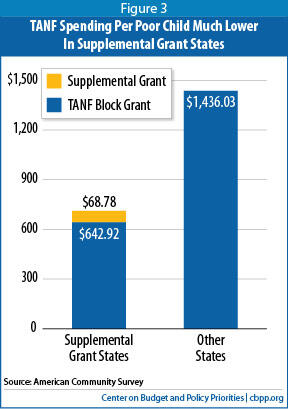

The expiration of the Supplemental Grants is a significant loss to the 17 states that count on them to assist vulnerable families. These states already receive less than half the amount of federal TANF funds per poor child that other states do, even after counting their Supplemental Grants. In most of these states, the grants have accounted for nearly 10 percent of the state’s annual federal TANF allocation (see the appendix table). Despite their name, the Supplemental Grants have been an integral part of the TANF funding formula since the program’s inception; they are not treated as supplemental funds by the states that receive them, and Congress has consistently renewed the grants since 1996.

The expiration of the Supplemental Grants will deprive these 17 states of roughly $108 million, including a $28 million reduction in the grants for the current quarter and the loss of all $80 million of the grants for the remaining three months of fiscal year 2011. Already facing severe budget shortfalls, many of these states are almost certain to respond with even deeper TANF cuts than they have already implemented or proposed.

Representative Lloyd Doggett (D-TX) submitted legislation last week that would fund the Supplemental Grants through September 30, 2011. This would restore funding that states are counting on to support vulnerable families and place the Supplemental Grants on the same renewal timetable as the TANF block grant, which expires on September 30. Since Congress created the Supplemental Grants as an integral part of TANF under the 1996 welfare law, it would be appropriate to thoroughly review these grants along with other aspects of TANF during TANF reauthorization deliberations. Congress should not allow the deal that it struck with the states in 1996 to unravel without first examining whether the Supplemental Grants are still needed (or should go to a new group of states that meet the grants’ original eligibility criteria). Many changes have occurred in the 15 years since TANF was created; policymakers should reconsider the Supplemental Grants along with other aspects of TANF, rather than eliminate funding that states depend upon to serve poor families that have nowhere else to turn for assistance, especially when states — facing budget crises — have little or no ability to make up the loss of funding.

Supplemental Grant States Have Above-Average Child Poverty and Below-Average Federal TANF Funds Per Poor Child

To address the disparities that resulted from the TANF funding formula, Congress decided to supplement the $16.5 billion in basic annual TANF funding with Supplemental Grants for states with low federal AFDC spending per poor child and states with rapidly growing populations. The term “Supplemental Grants” is something of a misnomer. These grants are not supplemental in the sense of being add-ons; they were designed as an integral part of the TANF allocation formula. Senator Connie Mack (R-FL) made this point during the Senate floor debate before the passage of the 1996 welfare reform law:

The Hutchison[2] formula has been inappropriately referred to as a “supplemental” grant to states. This is a misleading characterization of the additional moneys provided in this legislation. In reality the Hutchison formula in the underlying legislation begins to chip away at historical inequities between States due to the Federal Government’s present system of awarding AFDC moneys. [3]

Indeed, these are among the poorest states. The child poverty rate in the 17 states that receive Supplemental Grants averaged 22.4 percent in 2009, 4.3 percentage points higher than the average for the other states and 2.7 percentage points higher than the national average (see Figure 2). Four of the five states with the highest child poverty rates in the country receive Supplemental Grants: Mississippi (with a child poverty rate of 30 percent), Arkansas (27 percent), and New Mexico and Alabama (25 percent).

In addition, if the number of poor children continues increasing for the next few years, as many analysts expect based on poverty trends following previous recessions, the amount of TANF block grant funding that states receive per poor child will decrease, since the total federal block grant funding level remains frozen regardless of changes in poverty. This decline would not be confined to states receiving a Supplemental Grant, but the impact would be greater in those states, since they would also lose their Supplemental Grant funds.

As noted, Supplemental Grant states already receive less than half the amount of federal TANF funds per poor child than other states do, even counting their Supplemental Grants. On average, in 2009, these states received $712 per poor child ($643 in block grant funds and $69 in Supplemental Grants), compared to $1,436 per poor child in other states (see Figure 3).

Loss of Funds Will Harm Already-Tight State Budgets

Allowing the Supplemental Grants to expire on July 1 would reduce TANF funding for the 17 Supplemental Grant states by about $108 million for this fiscal year. The Supplemental Grants are an important source of funding for the majority of states that receive them (see appendix table), accounting for about 10 percent of the total federal TANF funds they receive.

Florida, with an unemployment rate of 10.6 percent and a TANF caseload increase of 26 percent between December 2007 and December 2009, will lose $20.4 million in funding, the largest amount of any state. Three other states — Texas, Georgia, and North Carolina — will each lose more than $10 million in funding. Supplemental Grants account for more than 10 percent of total federal TANF funds in eight of the 17 states: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Georgia, Idaho, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Utah.

These cuts will occur in states that are not only poor but also faced significant budget gaps for the upcoming fiscal year (which begins for most states on July 1). Fourteen of the 17 states faced shortfalls for fiscal year 2012 that totaled $24 billion and accounted for as much as 37 percent of their budgets (see appendix table). While states in general have seen somewhat stronger-than-expected revenue growth in recent months following the largest revenue collapse on record, their budgets are just beginning to recover.

In response to these budget gaps and the lack of federal funding, states already have reduced or eliminated funding for some core TANF programs. Across the country, states are cutting benefits to unemployed families and scaling back programs that help unemployed TANF recipients find employment and help low-wage workers make ends meet. States also are requiring caseworkers to assist more families (thereby reducing the amount of attention they can provide to individual families). Some examples of cuts that states have implemented include:

- New Mexico has reduced monthly benefits for a family of three from $447 to $380 (from 29 percent to 25 percent of the poverty line) and suspended a program that encourages families to move from welfare to work by providing a transitional benefit to families that obtain a low-wage job.

- Arizona, which last year reduced the total amount of time that a parent and her family can receive TANF benefits from 60 months to 36 months over the parent’s lifetime, reduced it again to 24 months, one of the shortest lifetime time limits in the country. Arizona also is scaling back funding for child care subsidies, which will affect 13,000 children.

- Florida cut funding for substance abuse services for TANF recipients and other low-income parents, even though it recently enacted a new drug testing requirement for TANF recipients.

- Counties in Colorado, caught between a greatly increased TANF caseload and shrinking resources, are reducing funding for services designed to help families achieve self-sufficiency and address personal and family challenges.

The weakening of TANF’s core activities will make it more difficult for thousands of parents and guardians to provide for their families during hard economic times. It may also make it more difficult for states to meet their required work participation rates under TANF; states that fail to meet their target rate face a potential further loss of federal funds.[4]

Congress Should Fully Fund the Supplemental Grants Now and Revisit Them During TANF Reauthorization

The Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA) authorized the TANF block grant through September 30, 2010. The Claims Resolution Act of 2010 extended it through September 30, 2011 but provided funding for the Supplemental Grants only through part of the third quarter of federal fiscal year 2011. The TANF Supplemental Grants should be fully funded for this fiscal year — that is the fair thing to do for states that depend on these funds to provide assistance to very vulnerable families.

Congress created the Supplemental Grants as part of establishing TANF, and it would be appropriate to thoroughly review the grants along with other aspects of TANF during the TANF reauthorization deliberations. The Supplemental Grants were created to reduce the significant state-by-state disparities in funding per poor child under AFDC, which ranged from $400 to more than $2,000. As long as those disparities exist, the rationale for providing Supplemental Grants remains; Congress should not allow the deal that it struck with the states in 1996 to unravel without first examining whether the Supplemental Grants are still needed — or should go to a new group of states that meet the grants’ original eligibility criteria.

States already are struggling to respond to increased need with limited resources. Reducing those resources further risks seriously weakening states’ ability to assist struggling families that have nowhere else to turn for assistance. It also compromises states’ ability to maintain a strong work focus in their TANF programs. This is not what Congress intended when it reformed the welfare system in 1996. Helping welfare recipients meet their basic needs and find work in this weak economy requires more help from the federal government, not less.

| Appendix Table Supplemental Grant States Will Lose Substantial Federal TANF Funding While Already Facing Large State Budget Shortfalls | ||||

| TANF Supplemental Grants | Projected State Budget Shortfalls | |||

| Fully Funded Supplemental Grant as a Percent of Total Federal TANF Funding | Loss of Supplemental Grant Funding for Federal FY 2011 (in millions) | State FY 2012 Projected Shortfall* (in millions) | Shortfall as Percent of State FY 2012 General Fund Budget* | |

| Alabama | 10.62% | $3.75 | $979 | 13.4% |

| Alaska | 12.93% | $2.33 | $0 | --- |

| Arizona | 10.68% | $8.10 | $1,500 | 17.0% |

| Arkansas | 9.87% | $2.10 | $0 | --- |

| Colorado | 9.07% | $4.59 | $450 | 6.2% |

| Florida | 9.70% | $20.45 | $3,700 | 11.5% |

| Georgia | 10.13% | $12.62 | $1,300 | 7.6% |

| Idaho | 10.30% | $1.18 | $92 | 3.6% |

| Louisiana | 9.40% | $5.76 | $1,600 | 19.4% |

| Mississippi | 9.42% | $3.06 | $634 | 13.8% |

| Montana | 2.89% | $0.38 | $0 | --- |

| Nevada | 7.83% | $1.26 | $1,200 | 37.4% |

| New Mexico | 5.59% | $2.22 | $450 | 8.3% |

| North Carolina | 10.67% | $12.22 | $2,400 | 12.1% |

| Tennessee | 10.12% | $7.30 | SU** | NA |

| Texas | 9.78% | $17.84 | $9,000 | 20.5% |

| Utah | 10.32% | $2.95 | $390 | 8% |

| Total | 9.75% | $108.13 | $23,695 | 12.5% |

| Sources: Elizabeth McNichol, Phil Oliff, and Nicholas Johnson, “States Continue to Feel Recession’s Impact,“ Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; June 17, 2011, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=711. Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “FY 2011 TANF Contingency Fund and Supplemental Grant Awards Summary,” http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/ofa/policy/im-ofa/2011/im201104/im201104_contingency_fund.html . Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis. * These totals are the shortfalls that states faced. In recent months, many states have taken actions to close some or all of these shortfalls, primarily through various budget cuts. In most states, state fiscal year 2012 runs from July 1, 2011-June 30, 2012. ** SU = Shortfall size unknown. | ||||

End Notes

[1] For background on the Supplemental Grants and the TANF Contingency Fund, see Gene Falk, “Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) Block Grant: FY 2007 Budget Proposals,” Congressional Research Service, March 3, 2006, http://www.nationalaglawcenter.org/assets/crs/RS22385.pdf.

[2] The formula used to allocate the TANF Supplemental Grants was referred to as the Hutchison formula because Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison (R-TX) was one of its principal architects.

[3] Congressional Record at S13204, September 11, 1995.

[4] Under the TANF block grant, states must have a set share of families participating in work activities for at least a prescribed minimum number of hours each week. Generally, the share of families is 50 percent, but the target rate that a state must meet is reduced from the 50 percent target by one percentage point for each percentage point reduction in the state’s TANF caseload since 2005. A state that does not meet its work participation rate can face a federal fiscal penalty involving reduction of its block grant funding.

More from the Authors