The Outlook for Marketplace Open Enrollment

End Notes

[1] While there is no comprehensive survey of rate increases due to concerns about individual mandate enforcement, CareFirst, a major insurer in Maryland, Virginia, and Washington D.C., requested additional rate increases of 15 percent due to concerns about the individual mandate (https://www.vox.com/2017/5/8/15563448/trump-insurance-premiums-2018), and Pennsylvania’s insurance commissioner reported in June that insurers would request additional rate increases averaging 14.5 percent if concerns about mandate non-enforcement or repeal were not addressed (http://www.media.pa.gov/Pages/Insurance-Details.aspx?newsid=248). Insurers in a number of other states, including Alabama, Arizona, Indiana, Iowa, Louisiana, Oregon, and elsewhere, attributed a portion of their rate increases to concerns about mandate enforcement or to broader policy uncertainty.

[2] Rabah Kamal et al., “How the Loss of Cost Sharing Reduction Subsidy Payments Is Affecting 2018 Premiums,” Kaiser Family Foundation, October 27, 2017, https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/how-the-loss-of-cost-sharing-subsidy-payments-is-affecting-2018-premiums/.

[3] Matthew Fiedler, “Taking Stock of Insurer Financial Performance in the Individual Health Insurance Market Through 2017,” USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy, October 27, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/individualmarketprofitability.pdf.

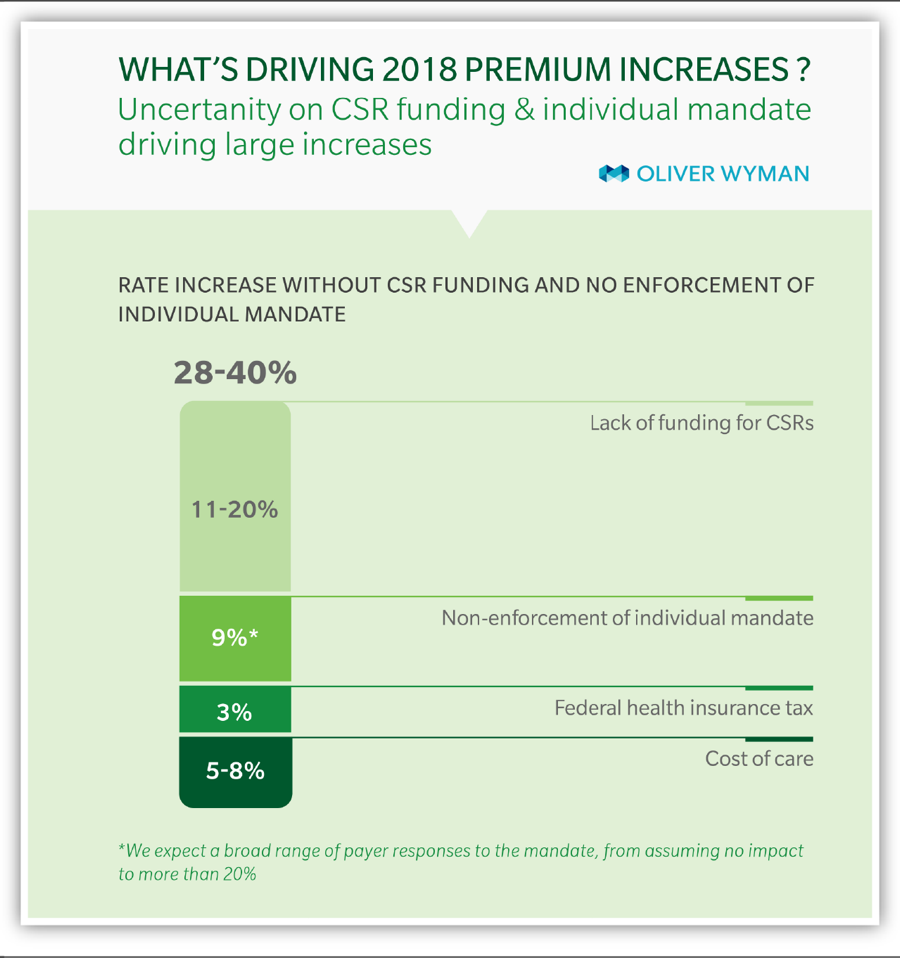

[4] Kurt Giesa, “Analysis: Market Uncertainty Driving ACA Rate Increases,” Oliver Wyman, June 4, 2017, http://health.oliverwyman.com/transform-care/2017/06/analysis_market_unc.html.

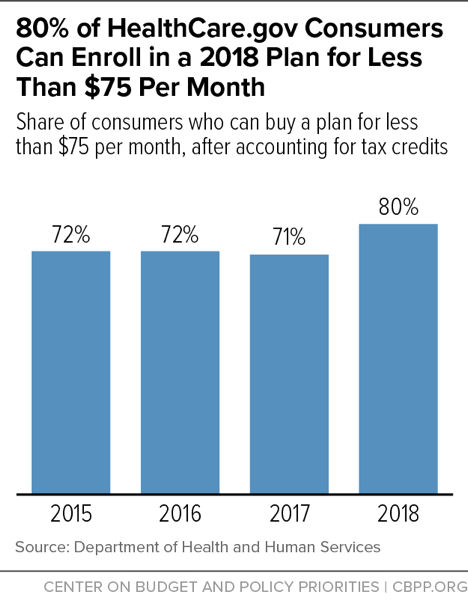

[5] Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “Health Plan Choice and Premiums in the 2018 Federal Health Insurance Exchange,” Department of Health and Human Services, October 30, 2017, https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/258456/Landscape_Master2018_1.pdf.

[6] For further discussion of the Administration’s outreach cuts, see Shelby Gonzales, “Trump Administration Slashing Funding for Marketplace Enrollment Assistance and Outreach,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 1, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/trump-administration-slashing-funding-for-marketplace-enrollment-assistance-and-outreach.

[7] Dylan Scott, “Trump Administration Abruptly Drops Out of Obamacare Events in Mississippi,” Vox, September 27, 2017, https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/9/27/16374158/obamacare-mississippi-hhs-events.

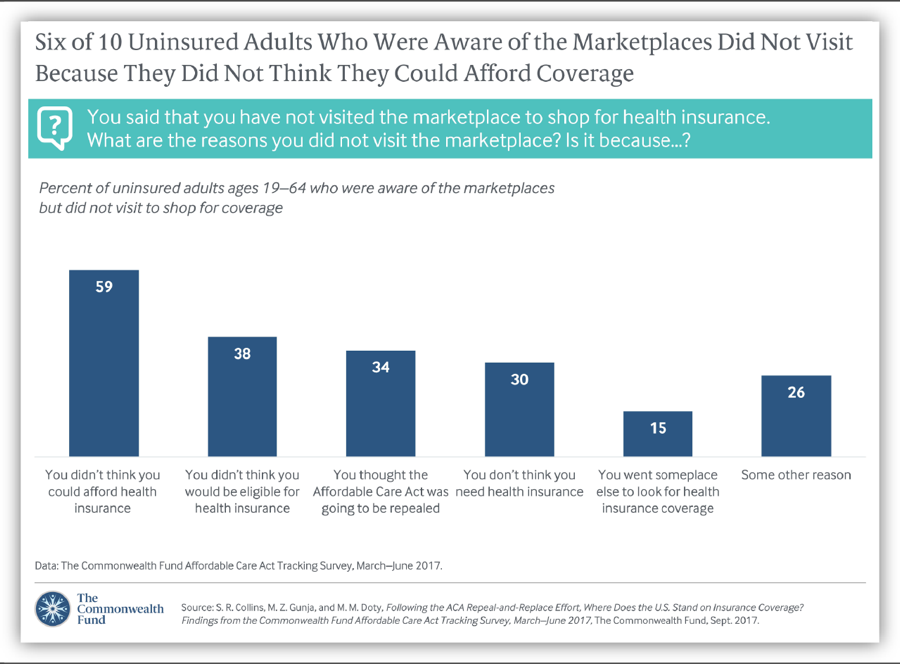

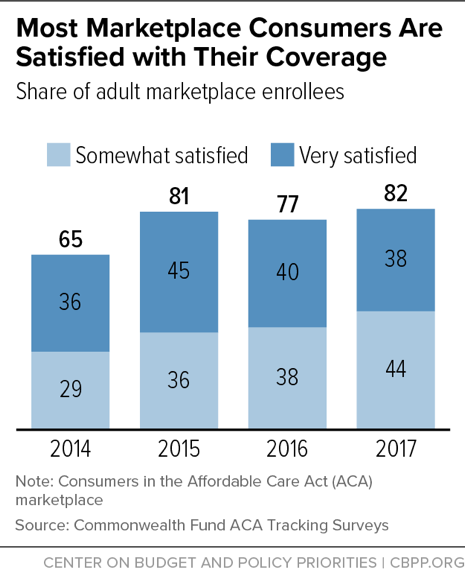

[8] Sara R. Collins, Munira Z. Gunja, and Michelle M. Doty, “Following the ACA Repeal-and-Replace Effort, Where Does the U.S. Stand on Insurance Coverage?” Commonwealth Fund, September 7, 2017, http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2017/sep/post-aca-repeal-and-replace-health-insurance-coverage and Commonwealth Fund, “Affordable Care Act Tracking Survey,” http://acatracking.commonwealthfund.org/.

[9] Jonathan Cohn, “Trump Administration Says Obamacare Ads Don’t Work, but Federal Study Says They Do,” Huffington Post, September 20, 2017, https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/obamacare-ads-trump-health-human-services_us_59c1dc7de4b0186c2206bdd3.

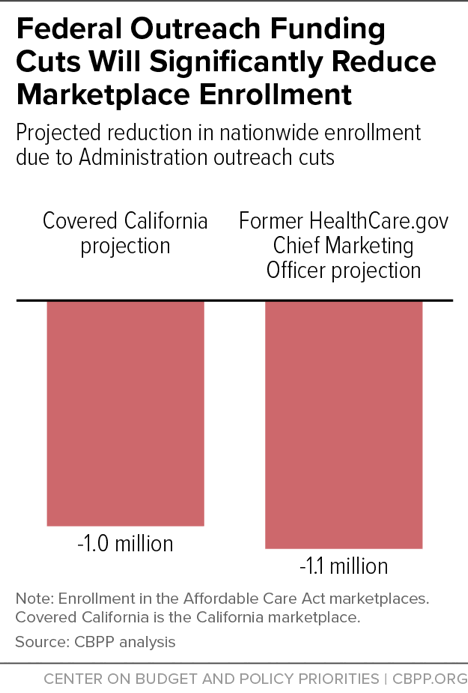

[10] Peter V. Lee et al., “Marketing Matters: Lessons from California to Promote Stability and Lower Costs in National and State Individual Insurance Markets,” Covered California, September, 2017, http://hbex.coveredca.com/data-research/library/CoveredCA_Marketing_Matters_9-17.pdf and Pinar Karaca-Mandic et al., “The Volume of TV Advertisements During the ACA’s First Open Enrollment Period Was Associated with Increased Insurance Coverage,” Health Affairs, April 2017, http://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1440.

[11] Joshua Peck, “Trump’s Ad Cuts Will Cost a Minimum of 1.1 Million Obamacare Enrollments,” Get America Covered, October 23, 2017, https://medium.com/get-america-covered/trumps-ad-cuts-will-cost-a-minimum-of-1-1-million-obamacare-enrollments-9334f35c1626 and Lee, op. cit.

[12] For a list of open enrollment deadlines in State-Based Marketplaces, see Louise Norris, “What’s the Deadline to Get Coverage During Obamacare’s Open Enrollment?” healthinsurance.org, October 2, 2017, https://www.healthinsurance.org/faqs/what-are-the-deadlines-for-obamacares-open-enrollment-period/.

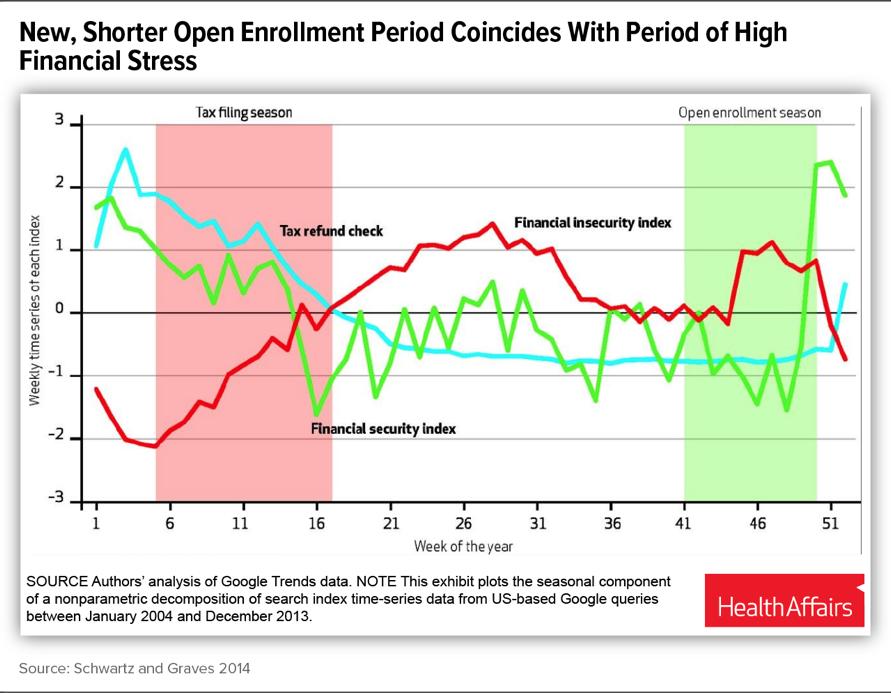

[13] Katherine Swartz and John Graves, “Shifting the Open Enrollment Period for ACA Marketplaces Could Increase Enrollment and Improve Plan Choices,” Health Affairs, July 2014, http://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0007#. Florida Blue, a major marketplace insurer, has also flagged this concern, noting in its comment letter on the HHS Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters for 2018: “It is well established that creating an [open enrollment period] that peaks between Thanksgiving and Christmas forces consumers to make financial decisions when their debt is at its highest levels and their interest in their health is at the lowest. Allowing sales in January helps, as consumer debt levels for subsidy eligible individuals are often off-set by the earned income tax credit and people generally have a renewed focus on their health.”

[14] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Strengthening the Marketplace by Covering Young Adults,” June 21, 2016, https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-06-21.html.

[15] See Amy Goldstein, “ACA Enrollment Schedule May Lock Millions Into Unwanted Health Plans,” Washington Post, October 20, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/aca-enrollment-schedule-may-lock-millions-into-unwanted-health-plans/2017/10/20/c2171008-b5ce-11e7-a908-a3470754bbb9_story.html?utm_term=.20478feb34cf.

[16] Morning Consult, National Tracking Poll #171011, October 19–23, 2017, https://morningconsult.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/171011_crosstabs_POLITICO_v1_AP-2.pdf.

[17] Ashley Kirzinger et al., “Kaiser Health Tracking Poll – October 2017: Experiences of the Non-Group Marketplace Enrollees,” Kaiser Family Foundation, October 28, 2017, https://www.kff.org/health-reform/poll-finding/kaiser-health-tracking-poll-october-2017-experiences-of-the-non-group-marketplace-enrollees/.

[18] Collins, Gunja, and Doty, op. cit.

[19] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “2017 Effectuated Enrollment Snapshot,” June 12, 2017, https://downloads.cms.gov/files/effectuated-enrollment-snapshot-report-06-12-17.pdf.

[20] Collins, Gunia, and Doty, op. cit.

[21] Ashley Kirzinger et al., op. cit.

[22] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “2017 Effectuated Enrollment Snapshot.”

[23] Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “About 2.5 Million People Who Currently Buy Coverage Off-Marketplace May Be Eligible for ACA Subsidies,” Department of Health and Human Services, October 4, 2016, https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/208306/OffMarketplaceSubsidyeligible.pdf. In addition, McKinsey analysts estimated that about 70 percent of consumers across the entire individual market have incomes below 400 percent of the poverty level. McKinsey Center for U.S. Health Reform, “Exchanges Three Years In: Market Variations and Factors Affecting Performance,” May 2016, http://healthcare.mckinsey.com/sites/default/files/Intel%20Brief%20-%20Individual%20Market%20Performance%20and%20Outlook%20%28public%29_vF.pdf.

[24] Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “Health Plan Choice and Premiums in the 2017 Health Insurance Marketplace,” Department of Health and Human Services, October 24, 2016, https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/212721/2017MarketplaceLandscapeBrief.pdf.

[25] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Health Insurance Marketplaces 2017 Open Enrollment Period Final Open Enrollment Report,” March 15, 2017, https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2017-Fact-Sheet-items/2017-03-15.html.

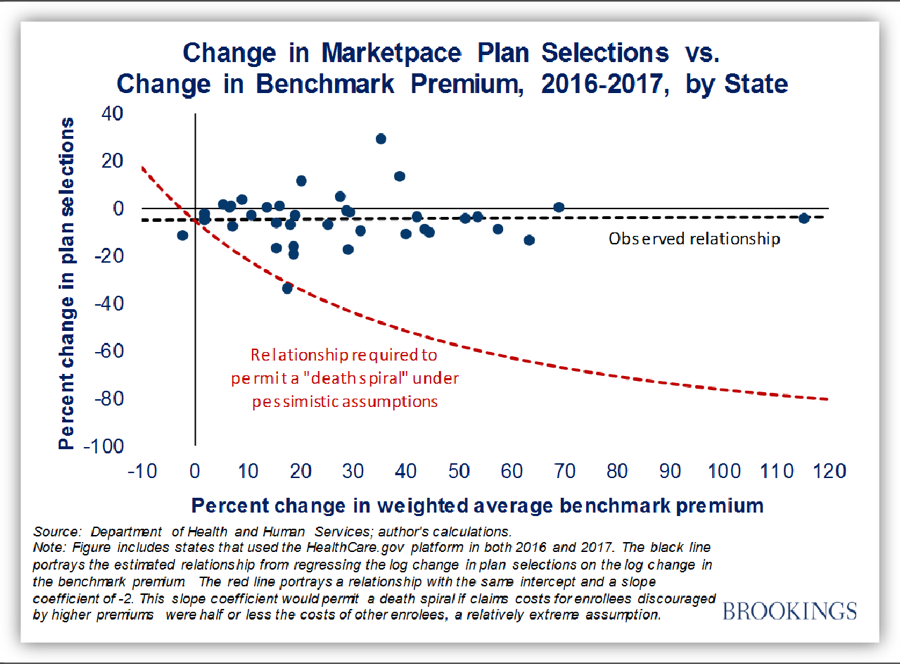

[26] Matthew Fiedler, “New Data on Sign-Ups Through ACA’s Marketplaces Should Lay ‘Death Spiral’ Claims to Rest,” Brookings Institution, February 8, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2017/02/08/new-data-on-sign-ups-through-the-acas-marketplaces-should-lay-death-spiral-claims-to-rest/; for analysis of earlier years, see Council of Economic Advisers, “Understanding Recent Developments in the Individual Market,” January 2017, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/page/files/201701_individual_health_insurance_market_cea_issue_brief.pdf.

[27] See https://public.tableau.com/profile/david3039#!/vizhome/StateSTrategiesforCSR2018/StateresponsestoCSRrisk.

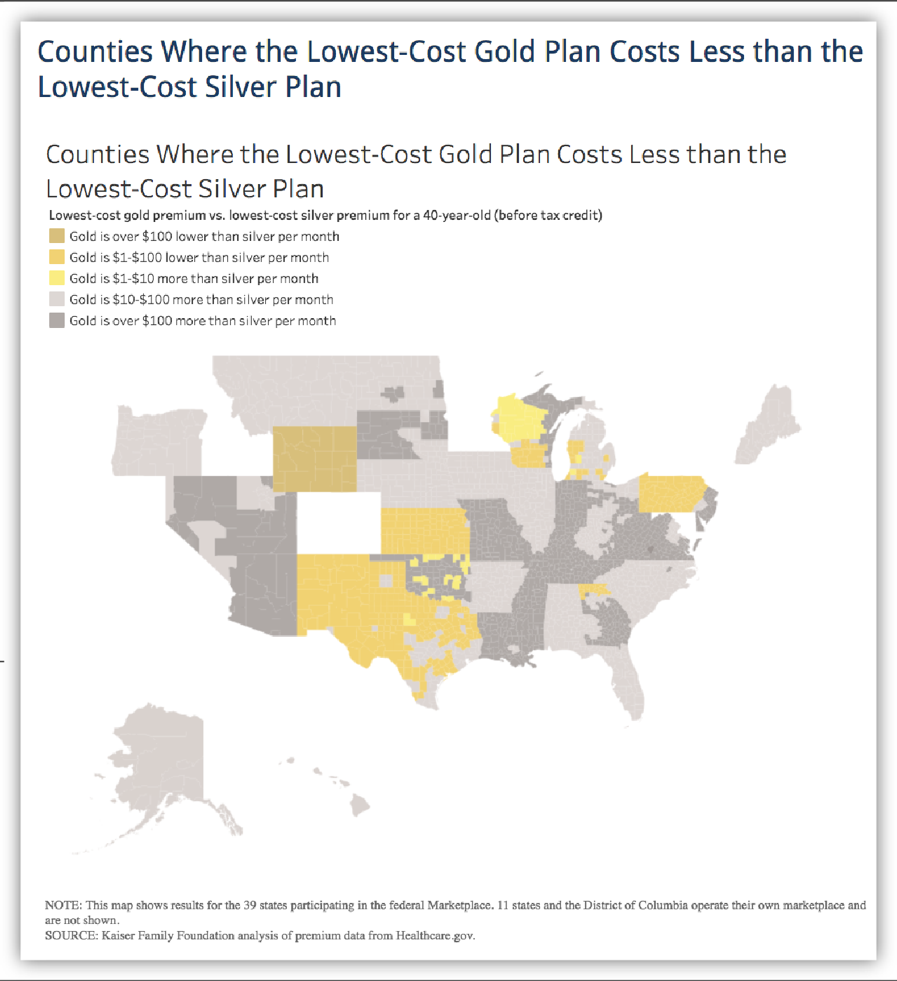

[28] Marketplace plans are categorized into metal levels based on the share of total health care costs covered by the plan versus covered by the enrollee through deductibles, coinsurance, and copays. Bronze plans cover about 60 percent of total costs, on average, and had median deductibles of $6,300 in 2016. Silver plans cover about 70 percent of total costs, on average, and had median deductibles of $3,000 (though much lower for consumers eligible for cost-sharing assistance). Gold plans cover about 80 percent of total costs, on average, and had median deductibles of $1,000. (Platinum plans, which are significantly less common, cover 90 percent of total costs on average, with median deductibles of $250.) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Data Brief: 2016 Median Marketplace Deductible $850, with Seven Services Covered Before the Deductible on Average,” July 12, 2016, https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-07-12.html.

[29] Ashley Semanskee, Gary Claxton, and Larry Levitt, “How Premiums Are Changing in 2018,” Kaiser Family Foundation, October 30, 2017, https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/how-premiums-are-changing-in-2018/.

[30] Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “Health Plan Choice and Premiums in the 2018 Federal Health Insurance Exchange.”

[31] Consumers with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty level (about $25,000 for a single adult, or about $50,000 for a family of four) are eligible for cost-sharing subsidies that reduce their silver plan cost sharing to well below the levels they would face in a gold plan. But consumers with incomes between 200 and 400 percent of the poverty level may want to consider options other than silver plans.

[32] In addition, insurers in some states are imposing CSR-related increases only for on-marketplace silver plans, not for those offered exclusively off-marketplace. Unsubsidized consumers in these states may be able to obtain lower premiums for silver coverage by purchasing coverage off-marketplace.

[33] Semanskee, Claxton, and Levitt, op. cit.

[34] Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, “Health Plan Choice and Premiums in the 2018 Federal Health Insurance Exchange.”