- Home

- HUD's Role In Rental Assistance: An Over...

HUD's Role in Rental Assistance: An Oversight and Review of Legislative Proposals on Rent Reform

Testimony of Will Fischer, Senior Policy Analyst, Before the House Financial Services Subcommittee on Housing and Insurance

Thank you for the opportunity to testify. I am Will Fischer, Senior Policy Analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The Center is an independent, nonprofit policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of federal and state policy issues affecting low- and moderate-income families. The Center’s housing work focuses on improving the effectiveness of federal low-income housing programs.

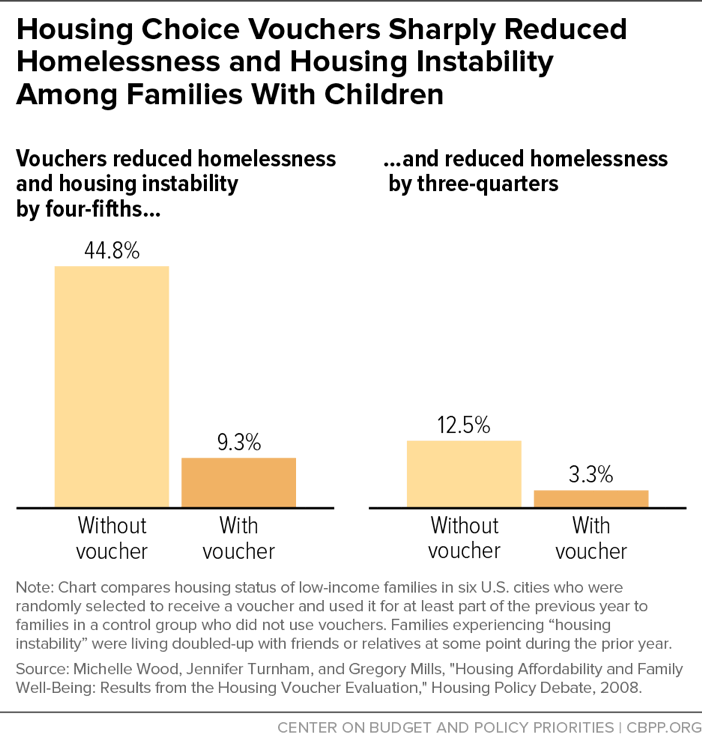

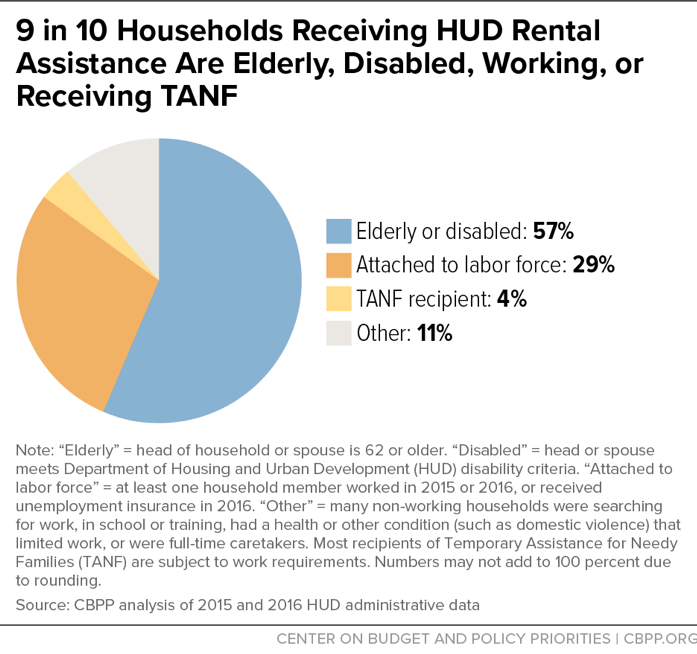

The nation’s rental assistance programs help more than 5 million low-income households — the great majority of them seniors, people with disabilities, and working families — afford decent, stable housing. Research shows that rental assistance is highly effective at reducing homelessness and housing instability, benefits that are linked to long-term improvements in outcomes for children. Policymakers should seek opportunities to strengthen rental assistance programs further, as Congress did in 2016 when it unanimously enacted the well-designed reforms in the Housing Opportunities Through Modernization Act (HOTMA), which this subcommittee developed. But it is also important to recognize that these are successful, evidence-based programs that help millions of Americans keep a roof over their heads, and to avoid changes that risk undermining that success.

The draft legislation the subcommittee is examining today, the Promoting Resident Opportunity through Rent Reform Act (PROTRRA), would be a step in the wrong direction that would fundamentally alter the Public Housing and Housing Choice Voucher programs in ways that are likely to make them far less effective.

- The bill would allow or require rent increases that would result in serious hardship for low-income people. For example, housing agencies today are permitted to charge the poorest families “minimum rents” of $50 a month even if this is more than the 30 percent of income families normally pay, but PROTRRA’s tiered rent option would raise this amount to over $500 on average — an enormous increase that would likely cause evictions and homelessness and force low-income people, including many working-poor families, to divert resources away from other basic needs.

- The bill is not well designed to advance the important goal of helping rental assistance recipients find and keep jobs and raise their earnings, and may do more to discourage work than promote it since many of its provisions — such as options for housing agencies to eliminate the child care deduction and public housing flat rents — would weaken supports and incentives for employment.

- PROTRRA would eviscerate many of the carefully crafted rent reforms in HOTMA. For example, to avoid causing hardship, HOTMA took care to allow the elderly and people with disabilities to deduct very high unreimbursed medical expenses from their incomes for purposes of rent determinations, even as it scaled back deduction of smaller expenses to streamline administration and trim costs. PROTRRA, by contrast, would authorize the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to eliminate the deduction entirely — a step HUD has made clear it wishes to take — and consequently raise rents substantially on some of the nation’s most vulnerable people.

- The bill would make it very difficult and expensive for HUD to provide the monitoring and oversight needed to ensure that taxpayer funds are properly spent, since it would allow nearly 3,800 state and local housing agencies to each choose their own rent systems (and even establish different rules for different programs and housing projects).

- The bill would create a major new barrier to voucher holders seeking to move from one community to another, since the complex patchwork of rent policies it would create would make it harder for families to understand what their rent obligations would be in different jurisdictions. Some families would find themselves unable to afford to move to areas that provide greater opportunities but use different rent policies. As a result, PRROTRA would move in the opposite direction from the draft Voucher Mobility Demonstration Act that the committee considered last week, which would promote regional cooperation to support voucher mobility.

- PROTRRA could lay the groundwork for sharp cuts to rental assistance funding, since — as has been the case with earlier rent increase proposals — proponents of cuts would likely point to the billions of dollars in rent increases the bill would allow as evidence that program funding can be cut without reducing the number of families assisted.

- The bill would make sweeping changes to rent rules affecting millions of low-income families and large amounts of federal expenditures before the policies it proposes have been adequately evaluated. At the direction of Congress, HUD has initiated rent reform evaluations that in the coming years will rigorously test most of the alternative rent policies PROTRRA proposes, but the results from those evaluations are not yet available.

Rather than enacting the sweeping changes in PROTRRA, policymakers should focus on ensuring that HOTMA is fully implemented as soon as possible and enacting the Family Self Sufficiency Act to support work among rental assistance recipients, and should defer consideration of further major changes until the results from HUD’s rent reform evaluations can be used to assess their likely impact.

Rental Assistance Today Is Highly Effective at Reducing Homelessness and Helping Working Families Make Ends Meet

Federal rental assistance helps close to 5 million low-income households afford decent, stable housing. Families with rental assistance generally pay rent equal to 30 percent of their income after deductions for items such as certain unreimbursed child care and medical expenses. This system is designed to enable families to afford decent stable homes and have enough money left over to cover other essential needs, while also limiting program costs.

A strong body of research shows that rental assistance under the current rules sharply reduces homelessness, housing instability, overcrowding, and other hardship.[1] In addition, by limiting families’ rent burdens, rental assistance frees up resources for other basic needs. Families with affordable rents on average spend more on food, clothing, and health care than those that pay very high shares of their income for housing. Overall, rental assistance lifted 4.1 million people above the poverty line in 2014, including 1.4 million children (using the federal government’s Supplemental Poverty Measure, corrected for underreporting of benefits).[2] In addition, stable, affordable housing can enable vulnerable groups such as frail seniors and people with disabilities to live in the community rather than being placed in institutions, often lowering costs in other public programs as a result.

About two-thirds of non-elderly, non-disabled rental assistance recipients work or worked recently, and rental assistance plays a crucial role in enabling working families to avoid eviction and make ends meet. The median working household with a voucher or Project-Based Rental Assistance would have to spend 60 percent of its $1,500 monthly income on housing if it did not have assistance. Research suggests that HUD’s Family Self-Sufficiency (FSS) program, which provides employment counseling, service referrals, and financial incentives to encourage work and support savings, can further increase employment and earnings among rental assistance recipients. FSS only reaches a small share of rental assistance recipients today, but the Family Self-Sufficiency Act (H.R. 4258), which the House passed in January with overwhelming bipartisan support, would expand and strengthen the program.

Rental assistance plays a particularly significant role in improving the well-being of children, since by providing stable housing rental assistance can profoundly affect other dimensions of children’s lives for the better. For example, one rigorous study in which homeless families received rental assistance found that the assistance lowered the chances that a child would be removed from his or her family and placed in foster care and reduced the frequency with which children had to switch schools. In addition, children in these families experienced fewer sleep disruptions and behavioral problems and were likelier to exhibit positive social behaviors (such as offering to help others or treating younger children kindly). The assistance also resulted in lower rates of alcohol abuse, domestic violence, and psychological distress among the adults with whom children lived.

In short, rental assistance under the current rent rules is an evidence-based intervention that provides crucial assistance to millions of low-income people. Policymakers should seek to further improve rental assistance rent rules where possible, and this subcommittee has played a central role in developing careful, bipartisan policy changes to do that. Policymakers should, however, also take care to ensure that any changes do not jeopardize the vital benefits that rental assistance provide today.

HUD Should Implement HOTMA and Complete Rent Evaluations Before Policymakers Consider Major Additional Changes

Congress unanimously enacted substantial reforms to rent rules — as well as other aspects of the rental assistance programs — as part of HOTMA in July 2016. HOTMA includes a series of well-designed changes that will reduce program costs, ease administrative burdens, and strengthen work incentives, while also ensuring that rental assistance continues to make housing affordable for the neediest families.

The HOTMA reforms reflected years of policy development and were supported by an unusually broad range of housing stakeholders. HUD has not yet issued implementing regulations for HOTMA’s rent provisions, so those provisions have not yet gone into effect. It would be difficult to justify making major additional changes to rent rules — and particularly changes like those in PROTRRA that would sweep aside many of HOTMA’s provisions — until the HOTMA changes have been fully implemented and their impact can be assessed.

Additional rent policy changes beyond those in HOTMA may ultimately be warranted. But any changes should seek to retain the core characteristics that have made rental assistance effective, including providing adequate assistance to enable the lowest-income families to avoid eviction and homelessness and providing families access to a broad range of neighborhoods. Moreover, any proposed changes that pose significant risks to low-income families should be rigorously evaluated on a pilot basis. HUD is already evaluating some alternative rent policies and plans to begin an evaluation of others soon.

- HUD’s Rent Reform Demonstration is testing a package of policies that includes higher minimum rents, reducing the frequency of income reviews to every three years, calculating rent based on a percentage of gross income, and simplifying utility calculations. Final results from the evaluation are expected in 2020.

- HUD plans this year to begin implementing a 100-agency expansion of the Moving to Work (MTW) demonstration that Congress approved in 2015. HUD has indicated that it will include a rent reform component in the expansion that will rigorously evaluate tiered rents (in which all families in an income tier pay the same rent) and stepped rents (in which rents rise the longer a family receives rental assistance).

Taken together, these evaluations — both of which are being conducted at the direction of Congress and using federal funds for research — will test most of the alternative rent policies included in PROTRRA. Congress should allow the evaluations to be completed before it even considers extending these policies more broadly.

Draft Rent Bill Would Reduce Effectiveness of Rental Assistance

The discussion draft of PROTRRA would radically alter federal rental assistance in ways that would reduce its effectiveness, by allowing or requiring major changes to rent rules covering the Housing Choice Voucher and Public Housing programs as well as projects receiving Project-Based Rental Assistance (PBRA) under the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD).

Rent Increases Would Create Serious Hardship

PROTRRA would raise rents for low-income people with rental assistance in three ways:

- It would give housing agencies the option to replace current rent rules for non-elderly, non-disabled recipients with a series of new options (most of which would allow or require substantial overall rent increases), or to design their own rent systems.

- It would give HUD authority to raise rents on the elderly and people with disabilities, which HUD would almost certainly do since it has specifically requested such authority in the past.

- It would allow housing agencies to use 40 percent of their voucher funds for shallow subsidies that would require low-income people to pay far more in rent than they do under current rules and make it difficult for them to rent outside of high-poverty neighborhoods.

Alternative Rent Systems for Non-Elderly, Non-Disabled Households Would Raise Rents

Housing agencies would be permitted to choose among six options — the current rent rules[3] and five alternatives.

-

Tiered rents. Agencies could adopt a rent system in which families are placed into three tiers, for those with extremely low incomes (with incomes at or below the higher of the poverty line or 30 percent of the local median income); very low incomes (below 50 percent of the local median); and low incomes (below 80 percent of the local median). Rents for the bottom two tiers could be set above what almost any family in those tiers would pay today, and overall 94 percent of families could pay higher rents.

Tiered rents would have their harshest impact on the lowest-income families. All three-person households in the lowest tier could be required to pay at least $520 per month, and much more than that in some parts of the country. Overall, households in the lowest tier could be charged up to $560 on average. Currently housing agencies are permitted to charge the poorest families a “minimum rent” of up to $50 a month, even if that is more than 30 percent of the families’ income. For the average household, tiered rents would effectively raise this minimum rent to more than 11 times the current level. Even if housing agencies opted to set tiered rents substantially below the maximum amounts permitted, this would still result in large rent increases for families near the bottom of tiers.

Families with very little or no income — such as those where a parent has lost a job and (like many low-wage workers) is not eligible for unemployment insurance — would rarely be able to afford a rent of hundreds of dollars a month and would face eviction and sometimes homelessness. But tiered rents could also impose hardship on a wide range of working-poor families. For example, a mother of two with a voucher who works 30 hours a week at the minimum wage could see her rent more than double to 60 percent of her income, leaving her with only $350 a month for necessities like clothing, diapers, school supplies, and personal care items for herself and her two children (as well as food or medical needs that aren’t met by other assistance her family may receive).[4]

-

Stepped rents. Agencies would also be permitted to establish a system of stepped rents that would rise every two years a family receives assistance, regardless of the family’s income. The stepped rents would be set at levels that would raise rents for most rental assistance recipients. As with tiered rents, this option would sharply raise the minimum rent, to more than $200 on average for households in their first two years of receiving assistance and much higher amounts for families that receive assistance for longer periods.

Stepped rents would act as a de facto time limit on assistance for many families, since after eight years (and sometimes six or fewer) the amount of rent that families are required to pay would often exceed the market rent for their unit, reducing their subsidy to zero. Even before that, many families would likely be displaced from their homes because they would not be able to afford the required rents. Families affected by stepped rents would be eligible for a hardship exemption if needed, but HUD data show that an existing exemption for families affected by minimum rents protects few families — in part because it requires households to apply for an exemption, but eligible households may not know that exemptions are available or how to apply if the housing agency doesn’t adequately publicize the policy.[5]

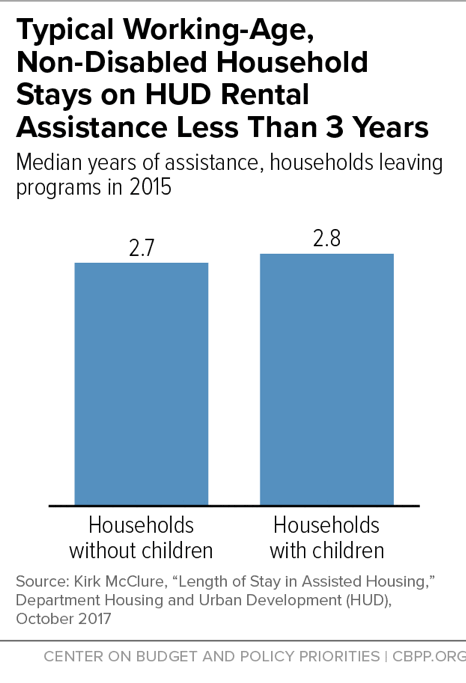

The majority of non-elderly, non-disabled families receive rental assistance for less than three years. Some need assistance for longer periods, however, in part because rents in much of the country exceed the amount that a low-wage worker can afford. Adults who receive assistance for more than three years are substantially more likely to be working, compared to those who receive assistance for shorter periods.[6]

-

Rents at 30 percent of gross income with higher minimum rent. A third option would allow housing agencies to eliminate all income deductions, disregard most income from the household member with the second highest income (a small amount for most households), and increase minimum rents from $50 to $75. The rent increases under this proposal would be smaller than the massive increases that would occur under tiered and stepped rents, but they would still be difficult for many low-income families to afford.

The minimum rent increase would affect only the lowest-income families, those with adjusted incomes below $3,000. This group of extremely poor families, largely families with children, would have difficulty coming up with an added $25 a month, and would often be at risk of displacement from their homes.

The elimination of deductions would also fall mainly on families with children (along with those caring for disabled adults), who are now permitted to deduct $480 from their income per dependent per year. And the largest increases would be paid by working parents who currently deduct unreimbursed child care expenses. The elimination of the child care deduction would sweep aside one of the key compromises made during consideration of HOTMA. The initial draft of that bill would have scaled back the deduction, but the leadership of the Financial Services Committee decided to retain the full deduction after some members expressed concern that eliminating it would cause hardship and reduce support for work.

- Elimination of public housing flat rents. The bill would also allow housing agencies to maintain rents at 30 percent of adjusted income, but eliminate a policy that allows families in public housing to choose to pay a flat rent based on the market rent for comparable units. This would result in rent increases for public housing residents that pay flat rents today. Policymakers instituted flat rents to encourage families with a range of incomes to live in public housing, out of concern that concentrating very poor families in public housing resulted in higher crime and other adverse effects. Without flat rents, many working families would likely move out of public housing if their income rises to the point where they would be required to pay an income-based rent significantly above the market rent.

- Agency-designed rents. The bill would also allow agencies to design their own rent rules, which could raise rents to any level. Agencies would have to submit their policies to HUD for approval, but they would automatically be considered approved if HUD did not reject them within 90 days. It is unlikely that HUD — whose capacity would already be strained by the task of overseeing the complex system PROTRRA would create — would be able to carry out a meaningful review process in this time frame if large numbers of agencies propose alternative rules.

Rent Would Likely Rise for Seniors and People with Disabilities

PROTRRA would permit HUD to require that all housing agencies charge elderly and disabled residents a percentage of their gross income, without any deductions. HUD would determine the percentage, subject to a requirement that it must increase or hold constant overall rent payments received by housing agencies. Thus, HUD could require that elderly and disabled households pay more than 30 percent of gross income.

HUD would almost certainly use this authority to increase rents on elderly and disabled households, since it has already proposed charging rental assistance recipients — including seniors and people with disabilities — rents set at a percentage of their gross income. HUD’s fiscal year 2018 budget requested authority to set rents at 35 percent of gross income — including for the Section 202 and Section 811 programs, which exclusively target the elderly and people with disabilities. Draft HUD legislation that leaked in February 2018 would set rents for the elderly and people with disabilities at 30 percent of gross income. (HUD indicated later that it would propose exempting current recipients from this increase, but not equally needy people who come off waiting lists in the future.)

If HUD used the PROTRRA authority to set rents at 30 or 35 percent of gross income, this would raise rents for virtually every elderly or disabled household. The policy would eliminate the existing elderly/disabled standard deduction and the deduction for excess medical and disability expenses. Seniors and people with disabilities with high unreimbursed medical expenses would face the largest increases. This is particularly striking because HOTMA took care to retain a deduction for very high unreimbursed medical expenses for purposes of rent determinations, even as it scaled back deduction of smaller expenses to streamline administration and modestly trim costs.

Shallow Subsidy “Option” Would Risk Weakening Rental Assistance for Seniors, People With Disabilities and Others Who Need It Most

PROTRRA would also allow housing agencies to divert up to 40 percent of their voucher funds to shallow subsidies with a payment standard (a cap that determines the maximum rent a voucher can cover) between 20 and 40 percent of their regular voucher payment standard. For many families, the subsidy available under this policy would leave them unable to afford decent stable housing. This policy would thus replace vouchers — an evidence-based policy proven by rigorous research to be the single most effective policy for reducing homelessness — with an untested shallow subsidy that seems likely to be far less effective at addressing problems like homelessness and housing instability. Shallow subsidies would also make it more likely that families would feel compelled to live in the lowest-rent neighborhoods, which often also have high-crime rates and poor-performing schools.

Housing agencies would offer the shallow subsidy to households on the waiting list for assistance, and those that accept would be able to jump ahead of other families and be assisted immediately — but would then no longer be in line for a voucher under the regular rules. PROTRRA presents the shallow subsidy as an option for families, but many poor people would feel pressure to accept shallow subsidies even though they may fall far short of what the recipient would need to afford decent, stable housing.

Take, for example, an elderly woman receiving the maximum federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefit of $750 a month and waiting for a voucher at an agency with a payment standard of $800 and a shallow subsidy set at 40 percent of the payment standard. Under the regular rules, when she reaches the top of the waiting list she could rent a unit with a rent at the payment standard and receive a subsidy of about $585, allowing her to pay $215 in rent and leaving most of her very modest income for other necessities. Under the shallow subsidy, if she rented a unit for $800 she would receive a subsidy of just $105 and would have to spend $695 — the bulk of her income — on rent, leaving her with very little for other basic needs and placing her at risk of eviction as those needs pile up.[7] She could refuse the shallow subsidy and hold out for a regular voucher — but that would mean that every family and individual on the waiting list that opts to accept the shallow subsidy would skip past her, leaving her without any rental assistance for as long as several additional years.

Bill’s Provisions Are Not Well Designed to Increase Earnings or Employment

Proponents of the approach taken by PROTRRA have suggested that it would increase earnings and employment by strengthening earnings incentives. Helping rental assistance recipients find and keep jobs and raise their earnings is an important goal, but the bill’s proposals could do as much to discourage work as support it.

Critics of the current rent rules at times argue that they discourage work because they raise a family’s rent by 30 cents for each added dollar in earnings, creating in effect a marginal tax on their earnings. But it’s important not to overstate this effect. There is no consistent evidence that rental assistance reduces employment in the long term, and the policy of setting rents based on 30 percent of adjusted income has the important benefit of providing the poorest families sufficient assistance to afford decent, stable housing while it avoids providing better-off families larger subsidies than they need.[8] In addition, the current rent rules avoid “cliffs” where subsidies are cut sharply when a family’s rent exceeds a specified level — a feature that is likely to increase work disincentives — because subsidies phase down gradually to zero. And once implemented, HOTMA will delay rent changes so that they do not occur until a year after earnings rise.

Moreover, research suggests that marginal tax rates in benefit programs do relatively little to influence wages and hours, in part because very low-wage workers generally have little control over their hours or ability to find higher-paying jobs and also have limited understanding of how benefits adjust as earnings change.[9] In addition, many factors other than the marginal tax rate influence employment and earnings among low-income individuals, including those receiving rental assistance. For example, rental assistance can support work by enabling families to afford housing that is accessible to jobs and avoid evictions that disrupt employment.

In any case, most of the rent options in PROTTRA do little or nothing to provide financial incentives for work, and most include provisions that would, if anything, discourage work:

- Tiered rents would hold rents constant when a family’s earnings vary within a tier, but would also establish cliffs at tier boundaries that would typically raise rents by more than $200 if the family earns one more dollar. It is difficult to predict the overall effects of tiered rents on earnings, which is one reason HUD’s planned evaluation of MTW tiered rents will be important to assessing the policy. But because of the large earnings penalties created by the cliffs, it is quite possible that if the policy had any effect on work it would be to discourage families from increasing their earnings.

- The gross rent option maintains a 30 percent marginal tax rate on most earnings and eliminates the child care deduction, taking away a significant work support from many rental assistance recipients, while establishing a new disregard for earnings of the second earner in a household that would affect only a small share of rental assistance recipients’ earnings.

- The elimination of public housing flat rents would mean that public housing residents with relatively high incomes would see their rents rise when their earnings increase, even if this requires them to pay above-market rents.

- Shallow subsidies would retain a 30 percent marginal tax rate, but would result in families losing assistance entirely at much lower income levels than is the case under regular voucher rules.

The stepped rent option would set rents that are entirely disconnected from a family’s earnings, so it would eliminate the current marginal tax on earning. But this policy would also risk disrupting many families who are already working and count on rental assistance to help them make ends meet. This is the case because families who have received rental assistance for an extended period — who would pay the highest rents under stepped rents — are disproportionately likely to work. Of the working families potentially subject to stepped rents, the majority have received assistance for more than four years, according to HUD data. More than 90 percent of those families would face rent increases and many would lose assistance entirely because their required payment would equal or exceed the market rent for their property.

Policymakers who want to help rental assistance recipients succeed should focus on strengthening Family Self-Sufficiency and HUD’s Jobs Plus initiatives, both of which use service coordination and incentives to support work and have shown promising results. The Family Self Sufficiency Act would be an important step in this direction. In addition, HUD should improve implementation of “Section 3,” an existing requirement that a portion of jobs and small business opportunities created through federal housing and community development investments go to public housing residents and other low-income people.

Local Rent Rules Would Make It Difficult for HUD to Prevent Misuse of Funds and Errors in Rent Determinations

PRROTRA would make determination of rents and subsidy levels vastly more complicated than it is today. The approximately 3,800 agencies that administer public housing, vouchers, or RAD Project-Based Rental Assistance would each choose among six options for determining basic rent rules, several of which are fundamentally different from each other and one of which would allow agencies to design and implement their own rules — potentially adding hundreds of additional sets of alternative rules. Moreover, agencies would be permitted to set different rules for the voucher, public housing, and PBRA programs, and even for individual housing projects, in addition to establishing a separate shallow subsidy subprogram within the voucher program.[10]

This would create a complex, fragmented system that would make it extremely difficult for HUD to ensure that taxpayer funds are spent properly, in a program that is entirely funded with federal dollars. HUD oversight plays a crucial role in ensuring proper implementation of rental assistance rules today. For example, after a 2000 report identified relatively widespread errors in determining tenant rents and subsidy levels, HUD took steps to strengthen monitoring and provide technical assistance, which has reduced errors by 67 percent.[11] Such quality control efforts would be far more difficult and expensive if rules varied from agency to agency, and virtually impossible if large numbers of agencies designed their own rent rules. A recent Government Accountability Office report found HUD already struggles to oversee local rent rules allowed under the Moving to Work demonstration, which currently includes just 39 agencies.[12]

Patchwork of Local Rules Would Block Voucher Mobility

Allowing widespread variation in rent rules would also make it much more difficult for low-income families with vouchers to use the voucher program’s portability option, which allows them to move from the jurisdiction of one agency to the jurisdiction of another — including to high-opportunity neighborhoods with low poverty and strong schools. Research shows that when voucher holders with young children move to low-poverty neighborhoods, children in those families earn substantially more as adults and are more likely to attend college and less likely to become single parents.[13]

There has been strong bipartisan interest in strengthening portability and taking other measures to support moves by voucher holders to high-opportunity neighborhoods. The 2016 “A Better Way” anti-poverty plan called for reform of the “fragmented national system” used to administer rental assistance, noting that it makes it more difficult for voucher holders to move and consequently “constrains individual choice and economic mobility.” This subcommittee held a hearing just last week at which members express bipartisan support for the Voucher Mobility Demonstration Act that would support regional coordination to promote voucher mobility.

PROTRRA would move in precisely the opposite direction by making the rental assistance system even more fragmented. The large variation and complexity of the rent policies allowed by the bill would create a major new barrier to voucher holders seeking to move from one community to another. Families may have difficulty understanding what their rent obligations would be under policies that different jurisdictions would adopt, and may not be able to afford to move to areas that provide greater opportunities but use different rent policies. Indeed, local agencies that wish to prevent portability — such as suburban agencies seeking to exclude voucher holders attempting to move from a nearby central city — could deliberately set tenant rents high enough to discourage voucher holders from moving in.

Bill Could Lay Groundwork for Funding Cuts

The rent increases permitted under PROTRRA would on paper be optional for agencies, but there would be a significant risk that enactment of PROTRRA would lead to funding cuts that would in turn place pressure on agencies to adopt rent increases. Each year, Congressional appropriators generally seek to provide adequate funding to cover all vouchers in use. If PROTRRA were enacted, housing agencies would have authority to raise rents to a level that would harm low-income families but would also reduce program costs by billions of dollars per year. It would then be highly likely that the Administration and some members of Congress would argue that federal funding should be cut, since agencies would have broad flexibility to increase rents to avoid or reduce subsidy terminations and help meet the cost of maintaining public housing.

This risk is illustrated by the Trump Administration’s first two budgets, both of which proposed sharp increases in tenant rents and argued that those rent increases would allow program funding to be cut by billions of dollars without reducing the number of families assisted. Similarly, the George W. Bush Administration proposed in its 2004 to 2006 budgets both to cut voucher funding sharply and to convert the voucher program to a block grant that would have given state and local agencies sweeping flexibility to reduce subsidies for families — and at times specifically argued that the new flexibility justified the funding cuts.

If PROTRRA enactment were accompanied or followed by funding cuts, local housing agencies would have to either adopt rent increases or reduce the number of families they assist. As a result, even agencies that do not wish to raise rents on low-income families could feel considerable pressure to do so.

Conclusion

Thank you again for inviting me to testify today. The nation’s rental assistance programs provide highly effective, evidence-based assistance that plays a crucial role in helping millions of low-income people keep a roof over their heads. This subcommittee and committee have been leaders in developing carefully designed legislation — like HOTMA and the Family Self-Sufficiency Act — to strengthen those programs while retaining the core characteristics that have underpinned their success. PRROTRA would move in a very different direction, by instituting radical, untested policies that are likely to harm low-income families and make federal rental assistance more complex and less effective. I look forward to answering your questions and stand ready to support your work to further improve federal rental assistance.

Chart Book: Rental Assistance Reduces Hardship, Promotes Children’s Long-Term Success

Chart Book: Employment and Earnings for Households Receiving Federal Rental Assistance

End Notes

[1] Will Fischer, “Research Shows Housing Vouchers Reduce Hardship and Provide Platform for Long-Term Gains Among Children,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated October 7, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/research-shows-housing-vouchers-reduce-hardship-and-provide-platform-for-long-term?fa=view&id=4098.

[2] CBPP analysis of 2014 Census Bureau data from the March Current Population Survey, SPM public use file, with corrections for underreported benefits from HHS/Urban Institute TRIM model.

[3] Agencies that retain the current rent policy would be permitted to review income every two years, rather than annually as current law requires for all families except those on fixed incomes.

[4] This assumes that she works four full weeks each month and receives the dependent deduction for her children but not a deduction for unreimbursed child care expenses.

[5] Moreover, PROTRRA would allow even weaker hardship exemption policies than those now required for minimum rents, since it would permit agencies to adopt any hardship policy previously used by an agency participating in the MTW demonstration, which are exempt from the standards for hardship policies that apply to other agencies. A recent Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found that while MTW agencies are required to have hardship policies, HUD had not established any standards for those policies and five MTW agencies reported that they had never received a request for a hardship exemption.

[6] Kirk McClure, “Length of Stay in Assisted Housing,” Department of Housing and Urban Development, October 2017, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/length-of-stay.html.

[7] This assume that she receives the $400 standard deduction for elderly and disabled households but not the deductions for high unreimbursed medical expenses.

[8] Will Fischer, “Research Shows Housing Vouchers Reduce Hardship and Provide Platform for Long-Term Gains Among Children,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 7, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/research-shows-housing-vouchers-reduce-hardship-and-provide-platform-for-long-term.

[9] Laura Tach and Sarah Halpern-Meekin, “Tax Code Knowledge and Behavioral Responses among EITC Recipients: Policy Insights from Qualitative Data,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, Vol. 33, No. 2 (Spring 2014), pp. 417 and 434; Jennifer L. Romich, “Difficult Calculations: Low-Income Workers and Marginal Tax Rates,” Social Service Review, Vol. 80, No. 1 (March 2006), p. 57.

[10] The separate rent rules could have disparate effects on different racial and ethnic groups, since at some agencies certain projects or programs have substantially different racial and ethnic composition than others.

[11] ICF International, “FY 2015 Final Report: Improper Payment for Quality Control for Rental Subsidy Determination Study,” prepared for Department of Housing and Urban Development, August 31, 2016, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/qualitycontrol-fy15.html.

[12] Government Accountability Office, “Improvements Needed to Better Monitor the Moving to Work Demonstration, Including Effects on Tenants,” January 2018, https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-150.

[13] Raj Chetty, Nathanial Hendren, and Lawrence Katz, “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children: New Evidence from the Moving to Opportunity Experiment,” American Economic Review 106, no. 4 (2016): 855–902.