Thank you, Vice-Chair Beyer and Chairman Lee, for the opportunity to testify before you today.

The U.S. economy is in a precarious place. More specifically, because of the pandemic-induced recession and the ongoing failure to control the spread of the coronavirus, tens of millions of Americans continue to experience severe disruptions to their lives and their living standards. New evidence shows that many risk hunger and eviction.[1] Over 30 million people — almost 20 percent of the current labor force — claimed unemployment benefits in recent weeks, and as members of this committee well know, they all potentially face a huge, negative shock to their incomes should their enhanced benefits expire a few days from now.

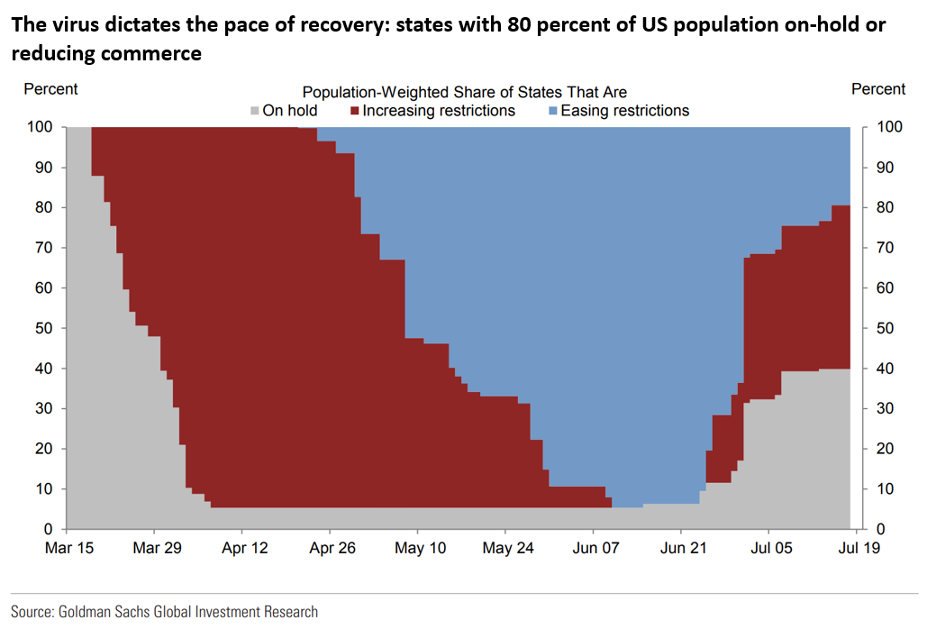

Small businesses are closing at an accelerated rate, business bankruptcies are up 26 percent from a year ago, and a whopping 80 percent of the U.S. population live in places where economic activity is once again retrenching due the spread of the coronavirus.[2] High frequency indicators of face-to-face commerce such as personal mobility, visits to restaurants, and travel—the type of activities most at risk in the age of the virus—are now showing sharp reversals from earlier progress. Up-to-the-minute labor market indicators (“real-time” data) suggest there is a fair chance that after strong job growth in May and June, payrolls in July may have contracted, on net.[3]

These unsettling trends are shaking the confidence of American businesses and households, while leading to great uncertainty about what the future holds. Furloughed employees worry about transitioning to the ranks of the permanently unemployed. Working parents with young children are fraught with uncertainty about school restarting in the fall, wondering what sort of child care arrangement they’ll need if schools remain even partially shut down. Businesses large and small are unable to reliably forecast revenues, invest in the future, or even know if they can make it for another month. State and local governments are facing their largest shortfalls in years, leading to job losses and great uncertainty regarding their outlook. And whatever burdens Americans face on average, they are far more significant for persons of color, who have been disproportionately hit by both the virus and its economic impact.

The single message of my testimony is that Congress must do all it can to reduce this uncertainty and give the American people reason to believe that the federal government is their reliable partner. They need to see that members of this body will work together with the requisite urgency to help them and their families and their businesses make it through to the other side of this crisis. I discuss the policies I believe would be most helpful to get there, policies chosen to both be responsive to the diagnosis offered below, and policies that have a positive track record. I understand and respect that others will have different ideas.

But what is not debatable is that the American people and the economy once again need your help and there is no plausible reason for such help to be delayed. In fact, to do so unnecessarily boosts uncertainty and reduces consumer and business confidence, while prolonging the pandemic, the downturn, and avoidable human suffering.

I begin with a set of figures showing the failure of virus control and its correlate, the challenging economic outlook. The data reveal both near-term economic weakness, as commerce recedes in the face of spiking virus cases, and longer-term weakness, as expectations are that the economy will remain weak for numerous years to come:

- The first set of figures (Figure 1) — total confirmed coronavirus cases in the U.S. and other advanced economies — shows the extent to which the U.S. is an outlier in terms of the sharply rising trend of new cases.[4] Because they’ve more effectively controlled the virus, the downturn was often far less negative in these other countries.[5] In Germany, for example, the most recent unemployment rate was 6.2 percent in May, when the U.S. jobless rate was more than twice that level, at 13.3 percent (the German jobless rate was also held by policy that kept workers connected to jobs, even at much reduced hours, an idea I endorse below).

- The next figure (Figure 2) shows why the U.S. economy has stalled in recent weeks, and why indicators that were improving are now flattening or reversing.[6] The figure shows that as of the second half of this month, states containing 80 percent of the U.S. population were either holding off on opening up commerce of reversing earlier re-openings. This is a sharp reversal from a month ago.

- The next figures are a set of bullet points based on “high-frequency” indicators, to provide the committee with some of the most up-to-date data points on the stalling economy:

- Last week’s unemployment insurance (UI) claims report showed that for the first time in 15 weeks, initial claims (people applying for UI) went up, in this case by about 100,000.[7]

- Over 30 million people are claiming UI benefits, many orders of magnitude above the historical average.[8]

- Analysts believe there’s a 50/50 chance that the jobs report out on August 7 will show that the number of jobs declined in July.

- The number of small businesses open in mid-July compared to January fell 16 percent in New York and California, and 18 percent in Texas.[9]

- In mid-July, 33 percent of renters (46 percent each for Black renters and Latino renters) indicated concern over their ability to pay their rent at the same time many eviction moratoriums are expiring.[10]

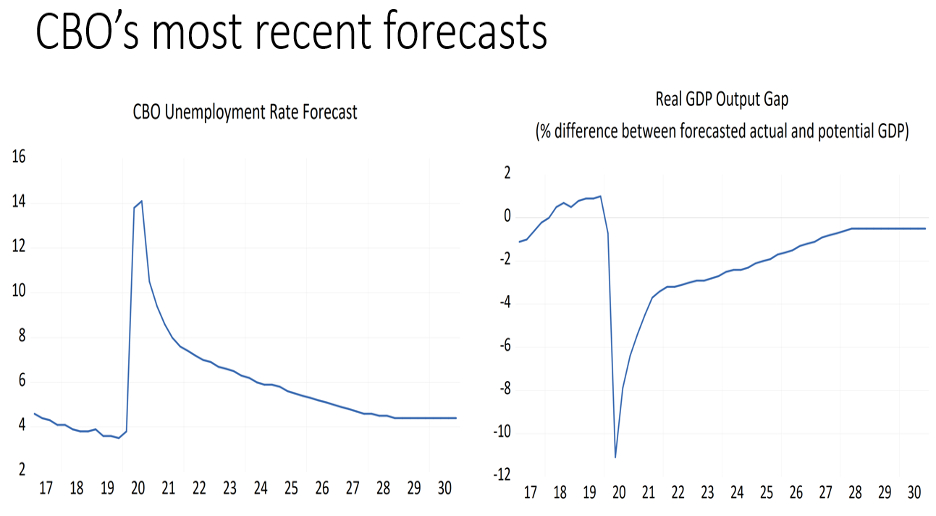

The final two figures (Figure 3) are intended to provide a longer-term view of the economic outlook, using the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) most up-to-date forecast.[11] The unemployment rate figure, on the left, shows the jobless rate to be elevated for years to come, and not expected to fall below 5 percent until 2027. The figure on the right shows the real GDP output gap: the difference between CBO’s forecast of real GDP and its estimate of GDP at full capacity. This year, the gap amounts to $1.4 trillion, or over $11,000 per household. Of course, these costs are not distributed on a per capita basis, and instead fall disproportionately on these least able to bear them: low-income families with no savings to fall back on; low-wage, displaced workers; and persons of color.

There are three distinct but related policy reactions that must continue to be taken during this crisis: the health care response, the monetary response, and the fiscal response. Given the urgency of the next relief package, currently under debate in the Congress, my testimony will largely focus on the latter.

As an economist, I will say little about the virus-control policies required by the health response. That said, I consider effective virus control far and away the most essential missing factor in the current and near-term-future economy. Mayors, governors, and even presidents can urge people to “get out there and spend,” but if majorities don’t believe they can safely engage in commerce at pre-crisis levels, evidence shows that official admonitions will not change their minds.[12]

Simply put, no virus control, no economic recovery. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell got this sequencing right when he recently said: “The virus is going to dictate the timetable here. The first order of business will be to get the spread of the virus under control, and then resume economic activity.”[13]

Speaking of the Fed, monetary policy is of course another essential line of defense and the central bank has done a good job thus far of providing support to credit markets and making sure the benchmark interest rate they control stays low. Some of the Fed’s lending facilities, especially those in the Main Street Lending Program, have provided less support to businesses than I expected and hoped for.[14] But even here, part of the purpose of these programs was to maintain low-cost credit to the full range of borrowers, from individuals to small businesses to corporations to municipalities, and based on diminished spreads of the relevant interest rates, that goal largely appears to be met thus far.

One of the goals of the Fed’s monetary policy creates a useful bridge to my main discussion about fiscal policy: the reduction of uncertainty in financial markets, something the Fed tries to achieve through “forward guidance” (telegraphing their thinking and plans to market participants). As this issue of uncertainty is the topic of this hearing, I will spend a few moments reviewing its relevance to economic outcomes.

It has long been recognized that people’s expectations about the future have a significant impact on their economic activity. A firm that foresees strong future demand for its product or service is far more likely to invest in expanded productive capacity than a firm that perceives declining demand. A breadwinner who is uncertain whether she’ll still have her job next month is less likely to make an investment or plan a vacation than a person with strong job security. A parent who doesn’t know whether her child will be in school or daycare a few weeks hence will worry about her ability to meet the demands of her job.

In a particularly timely example, a low-income, unemployed renter who doesn’t know how much she’ll receive in unemployment insurance next week may be uncertain about making her August rent. This, in turn, leads to chain of downstream uncertainties. Her landlord may be unable to make her mortgage payment and this, in turn, would be a stressor for the landlord’s lender.

In other words, uncertainties don’t just generate personal insecurities. They generate negative economic multipliers and policy should thus do all it can to diminish them. I’ve already emphasized the importance of congressional support for measures to reduce the spread of the virus, but it is also the case that the delay in the next relief package is another, totally avoidable source of uncertainty.

Expiring Pandemic Unemployment Compensation: Bad Micro, Bad Macro

A striking example of ramping up of unnecessary uncertainty, one with significant economic costs, is the high likelihood that enhanced unemployment benefits — the $600 plus-up from the CARES Act, called Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (PUC) — will very likely expire at the end of this month, as legislated in the CARES Act. Though economists and policymakers have different views about what the next extension should be, few believe that full expiration is warranted, either on a micro or macro level.

The good news is that congressional majorities appear to agree with the need to extend enhanced benefits. The bad news is that the debate over the issue started too late to avoid expiration. It is also of great concern that the Republican proposal in their new HEALS Act — cutting the $600 weekly plus-up to $200 and then requiring states to hit a 70 percent replacement rate[15] — represents a large benefit cut to 25 million jobless persons and their families at a time when the economy and job market are clearly weakening. On average, the cut from $600 to $200 would lower weekly benefits by 43 percent, according to UI expert Andrew Stettner.[16] In Utah, Chairman Lee, average benefits would fall 42 percent; in Virginia, Vice-chair Beyer, they’d fall 47 percent.

From a micro-perspective, unemployed families, especially those with low incomes, will risk significant hardship due to these losses. The 11 percent jobless rate and the fact that, as noted above, employment growth appears to be slowing, means that job seekers are in an unforgiving game of musical chairs, with far more players than seats. It is also the case that those in the bottom half of the income scale, disproportionately persons of color, have virtually no savings to fall back on. When they lose their paychecks, they face hunger and eviction.

Evidence from Farrell et al. show how important enhanced unemployment insurance (UI) benefits have been to recipients, as reflected by their spending.[17] They find that “Households that receive benefits soon after job loss show no relative decline in spending, while households that wait two months to receive benefits due to processing delays have large spending declines.” They also found that compared to still-employed workers, job losers experience spending declines averaging 20 percent before they received UI benefits. “This suggests,” they wrote, “that delays have imposed substantial hardship on benefit recipients.”

This last finding, regarding the hardship, and, I would add, the uncertainty invoked by delays in benefit receipt, should be at the top of mind of policymakers as the enhanced PUC benefits expire at the end of this month. As analysts from the Center of Budget and Policy Priorities recently documented, the weakening economy is contribution to growing hardships among vulnerable families, disproportionately families of color.[18] According to surveys on data from earlier this month, “About 26 million adults — 10.8 percent of all adults in the country — reported that their household sometimes or often didn’t have enough to eat in the last seven days…The rates were more than twice as high for Black and Latino respondents (20 and 19 percent, respectively) as for white respondents (7 percent)…An estimated 13.1 million adults who live in rental housing — 1 in 5 adult renters — were behind on rent for the week ending July 7. Here, too, the rates were much higher for Black (30 percent) and Latino (23 percent) renters than white (13 percent) renters.” These figures are significantly higher for families with children.

As discussed below, these hardships underscore the need for measures to both expand nutritional support (SNAP) and rental support, both of which were in the House-passed HEROES Act.[19] But they also elevate the risk factors invoked by allowing enhanced benefits to expire.

Because PUC takes the UI replacement rate to above 100 percent for most recipients — the median replacement rate is 134 percent — some critics of PUC have argued that it is creating a disincentive to work.[20] While there is, of course, logic to this claim, it is an empirical question which must be evaluated given the starkly over-supplied condition of the U.S. labor market. Work disincentives are a lot less biting when there’s not enough work.

In fact, various empirical facts challenge the disincentive story, all of which are more consistent with a labor market characterized by weak demand. For example, if current employers were competing with UI benefits, we would expect to see wage pressure among low-wage workers, as they have the highest PUC-induced replacement rates. But, controlling for distortionary composition effects, researchers at Goldman Sachs find low-wage trends doing slightly worse than higher-wage trends.[21] Similarly, they find that workers who were temporarily laid off and then rehired have smaller wage gains relative to those who weren’t laid off, again, the opposite prediction of the crowd-out theory. They conclude that there is “little evidence that either generous unemployment benefits or hazard pay have raised overall wages meaningfully.”

Economist Ernie Tedeschi asked a related question: do we observe diminished transitions from UI to work in places where replacement rates are highest?[22] He does so using micro-data on labor market transitions in May and June, finding “no evidence of any effect on labor market flows from more generous UI.” That is, the correlation between the replacement rate and the likelihood of transition to work was statistically insignificant (and, in some of his analysis, had the “wrong” sign, i.e., positive). Tedeschi also found that among those who left the UI rolls for work in June, almost 70 percent were making more on UI than in the prior job. Bartik et al. engage in a related analysis and find “no evidence to support the view that the temporary $600 supplement, which meant many workers received benefits higher than their wages, drove job losses or slowed rehiring substantially.[23]”

Weak labor demand is, as noted, a key factor in these findings, but so are UI rules that recipients must accept a “suitable job” if one is offered. Both these facts imply that PUC-induced work disincentives could become more evident if our virus-control policies improve, allowing for increased commerce. That speaks to the need for a dynamic, or “triggering” UI policy, where replacement rates fall as unemployment improves. Such a policy is especially notable in the context of this hearing, as it would reduce the uncertainty faced by tens of millions of Americans about the fate of this critical source of income. In this regard, making fiscal policy conditional on economic conditions is analogous to the “forward guidance” provided by the Federal Reserve, wherein they telegraph, to the extent practicable, their policy intentions to financial market participants. Such guidance has been found to be a powerful tool in meeting the Fed’s mandate by setting expectations and, key to our discussion today: reducing uncertainty.[24]

Triggering legislation has been proposed by, among others, Vice-Chair Beyer, and it has been challenged by those who argue that conditioning replacement rates on unemployment rates will just keep unemployment high as those with high replacement rates will refuse to seek work.[25] However, UI rules and some of the proposals are designed to obviate this concern. First, as noted above, recipients must accept suitable job offers or lose benefits. Second, some proposals gradually reduce enhanced benefits when virus control takes hold and the national emergency is declared over, at which point UI search requirements will also likely be reinstated.

Bottom line, unemployment will fall when labor demand returns in earnest, post virus control or vaccine. Until then, we should be mindful of potential work disincentives, but should definitely not assume their presence without empirical evidence.

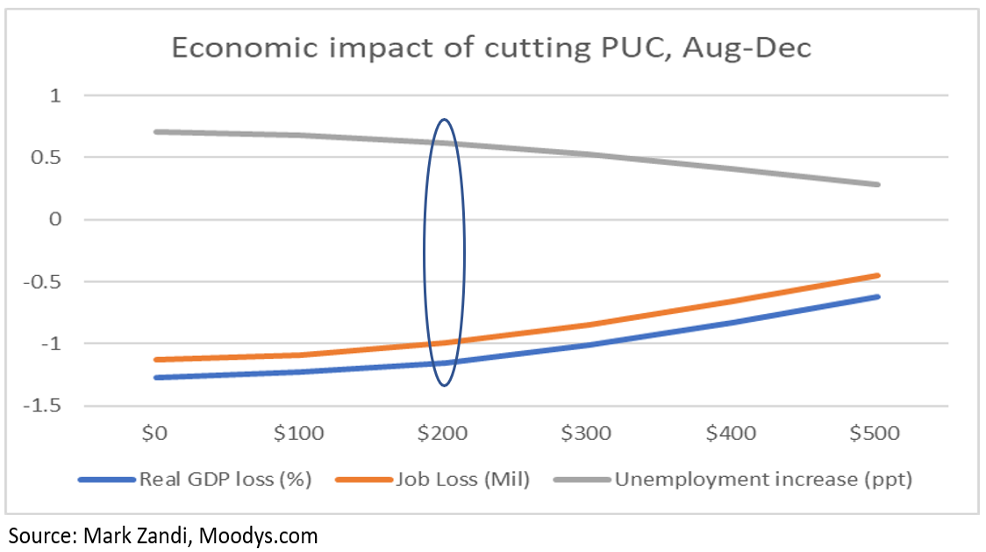

From a macro perspective, an expiration or even significant reduction of PUC would constitute a large, negative shock to an economy that is, as shown above, already operating far below capacity. On an annualized basis — meaning if these benefits were in effect for a year — the Bureau of Economic Analysis found that PUC amounted to about $840 billion (almost 4 percent of GDP), or $70 billion per month in May. Relative to maintaining the program for the rest of this year, allowing PUC to expire would be likely to lower real GDP by over 1 percent, cost more than a million jobs, and push up the unemployment rate by a bit less than 1 percentage point. In its July forecast, the CBO predicted the unemployment rate would be 10.5 percent in the last quarter of this year. These estimates suggest if PUC expires, the rate could be above 11 percent, probably comparable to its current level of 11.1 percent.

As noted, Senate Republicans have suggested reducing PUC from $600 per week to $200. The following figure (Figure 4), prepared by economist Mark Zandi, shows the extent of real GDP and job losses, and the increase in the unemployment rate throughout the rest of the year based on incremental reductions from the $600 plus-up.[26] For example, Zandi finds that taking the PUC down from $600 to $200 (see circled section in figure), is expected to reduce real GDP by 1 percent and jobs by about 1 million, and raise the unemployment rate by about 0.6 of a percentage point. Full expiration, should it lastingly occur, would lead to even larger losses, as shown in the figure. The bottom line is simple: such losses can and should be avoided.

The above analysis serves as a diagnosis of current conditions and suggests measures Congress should take as they design the next relief package. As the economy stalls due to inadequate virus control, concerns about hardships faced by vulnerable families loom large and must be foremost in considering specific policy interventions. Key areas include:

Evictions: As state and local eviction moratoria expire, policy measures to prevent renters’ evictions and foreclosures for homeowners. As noted, there is increasing insecurity in this area. Also, while Congress is reportedly considering a new eviction moratorium in the next relief bill, my understanding is that this measure would require beneficiaries to pay back accumulated rent once the moratorium is over. This not only implies a large, future demand on the incomes of vulnerable households; it also could undermine any positive economic impact of the moratorium, as renters are forced to save more and consume less than is good for their families or for the broader economy. To avoid this possibility, fiscal relief in this space is necessary such as the House’s HEROES included fulsome anti-eviction proposals, including “$100 billion in emergency rental assistance through the “Emergency Rental Assistance Act and Rental Market Stabilization Act.”[27]

Nutritional support: The HEROES Act also included a much-needed 15 percent temporary increase in SNAP benefits. Economists have consistently found SNAP benefits to have a relatively large economic multiplier, as benefits are a) quickly spent, creating more demand in the economy’s food sector and b) fungible, helping to free up other spending for low-income families.

Restore PUC enhanced UI benefits: As discussed in detail above, extending the weekly expansion at $600 per week is highly warranted and would not, based on evidence thus far, generate significant work disincentives. However, this disincentive would become more important as the job market improved, which motivates proposals to reduce the enhanced benefits as state labor market indicators improve.

State and local fiscal support: From what I glean from newspaper accounts, the next package may omit new fiscal relief for state and local governments, instead providing more flexibility on how states can spend previously legislated funds. This would be an egregious omission. As members know, these sub-national entities, which have recently shed 1.5 million jobs even while other sectors were adding employment, cannot run budget deficits. Their budgets are severely impaired, far more so than in the last downturn. In that recession, fiscal support through expanded FMAP was a highly useful tool for reducing layoffs of public workers and another policy that was found to have high multiplier effects.[28]

Support for vulnerable businesses with difficulty accessing credit: The sharp and sudden losses in revenues to many American businesses has been a huge source of stress, especially to smaller firms without ready access to credit. Even various government and Federal Reserve lending programs have mostly required businesses to go through banks to get the funds they need to survive, and for un- and underbanked businesses, particularly minority-owned firms, this barrier has been insurmountable. While the Paycheck Protection Program has had some success, I urge members of the committee to consider other proposals that seek to keep workers connected to jobs — employee retention programs — in some cases through credits or grants to employers. As my co-authors and I recently wrote in a review of these proposals, “By keeping workers on the job — or enabling employers to rehire them — an employee retention program would provide effective and cost-efficient support to workers and businesses. It would also help to facilitate the economy’s full recovery.”[29] That is, research shows downturns where otherwise-solvent companies were helped to survive the recession were followed by stronger recoveries. As noted above, Germany has long and effectively applied policies that kept workers connected to their firms, even at reduced hours. Such a policy, called “work-sharing,” exists in the U.S. context as part of our UI program, but while its use has grown considerably in the current downturn, it is still a tiny part of our support system. Administratively, to the extent that retention programs can deliver government grants versus bank loans, they will both be much more accessible and useful to vulnerable, small businesses.

Before concluding, I wanted to suggest that members of the committee not undercut the urgency of this moment due to concerns about the fiscal position of the federal government. There is little question that our public deficits and debt are headed for record territory as a share of GDP, with the latter — debt held by the public as a share of GDP — likely surpassing the record peak set in 1946 of 106 percent. Back then, we were fighting fascism; now, we’re fighting a deadly, highly contagious microbe, and both call for whatever temporary measures are necessary to protect our citizens and get to the other side of the crisis.

We are fortunate, in this regard, that interest rates on government debt are, and are expected to remain, very low in historical terms. Since 1990, the average yield on a five-year Treasury has been about 4 percent (the average Treasury debt maturity is about 5 years). As of this writing, that yield is 0.3 percent, meaning that debt service as a share of GDP is also historically low.[30] Indeed, compelling research shows that in weak economies like ours today, not taking actions to pull forward the next expansion can be more damaging to our fiscal accounts than engaging robust measures of the type discussed herein.[31] Simply put, the correct question about the current deficit is not “is it too big?” but “is it big enough to fully offset the demand contraction?”

Of course, none of this should be taken to imply that deficits do not matter. I have often testified before Congress stressing that as economies close in on full capacity, fiscal consolidation should occur, as private sector growth generates enough revenues to help chip away at the primary deficit.[32] In this regard, our most pressing, recent fiscal problem is not that our deficits are growing now, as they should. It’s that they were growing before the pandemic-induced recession, as the economy was closing in on full employment. As I have argued before, this troubling imbalance was far more a function of wasteful, regressive tax cuts than it was of extra spending.[33]

As we meet today, the absence of effective virus control is causing a reversal of reopenings in economies across the country, particularly in areas where the virus is spiking. It is unclear whether schools will open in the fall, and many businesses, including travel, tourism, entertainment, restaurants, and other face-to-face services remain highly stressed by the pandemic-induced collapse in demand. State and local government facing huge budget shortfalls have shed 1.5 million workers since February. Insecurity regarding hunger and evictions appears to be rising. Adding to all this uncertainty is the high likelihood that even while the July 31st expiration date for the $600-per-week PUC plus-up was known to every member of Congress, this essential income source for unemployed persons and their families could expire in days.

And while most Americans are experiencing some extent of these problems, they are particularly acute for persons and communities of color.

By working together to quickly implement significant fiscal relief in these and other areas, Congress can once again throw struggling people, places, and businesses the lifeline they need to make it to other side of this crisis. Along with uninterrupted enhanced UI benefits, I’ve argued for increased nutritional support, state and local fiscal relief, and help for smaller, more vulnerable businesses. Shortchanging such temporary fiscal relief due to deficit concerns would be, I have argued, highly misguided.

Finally, while I have tried to mostly stay in my economic lane, I have also stressed in the strongest terms that there will be no economic recovery until the virus is under control. This does not imply waiting for a vaccine. As I’ve shown, other advanced economies have implemented far more effective virus controls, and are therefore much better perched to restart at least some degree of commerce, schooling, and other critical aspects of life-before-COVID.

By forcefully taking charge of the public health aspects of the crisis and by ensuring that fiscal relief will be there as long and as deeply as people need it, Congress can help reduce the American people’s uncertainty and economic insecurity. I strongly urge you to do so and will be happy to help in any way I can.