BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Administrator Seema Verma says the large Medicaid coverage losses under Arkansas’ waiver may not be translating into higher uninsured rates. Of the 12,277 Arkansans who have already lost their Medicaid for not reporting enough work hours each month since the state in June became the first to implement such requirements, she said, “it’s very possible that people left the program because they found a job” and other health coverage. That argument, however, ignores the evidence from past Medicaid eligibility restrictions, other programs’ work requirements, and the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion. The overwhelming majority of those leaving Medicaid due to work requirements and other new eligibility restrictions (such as premium requirements and coverage “lockouts” for not meeting reporting deadlines) will likely become uninsured.

Policymakers in other states have used similar logic to justify work requirements. Kentucky’s Health and Family Services Secretary Adam Meier dismissed state projections that more than 95,000 people will lose Medicaid due to its waiver, suggesting that many would “graduate” from Medicaid to private coverage. And Virginia recently submitted a waiver that it says will test the “hypothesis” that the projected almost-30,000 drop in monthly Medicaid enrollment from its proposed work requirement is entirely due to people “obtaining employer sponsored or other commercial health insurance coverage.”

That hypothesis needs no testing, however. As we’ve detailed, the evidence already shows that:

-

Large numbers of enrollees will lose Medicaid because they don’t meet the new eligibility or paperwork requirements. If imposed nationwide, Medicaid work requirements would lead 1.4 to 4.0 million people (or 6 to 17 percent of those potentially subject to the policy) to lose coverage, Kaiser Family Foundation researchers showed, drawing on past experiences with eligibility restrictions in Medicaid and work requirements in other federal programs. These enrollees are projected to lose coverage not because they find jobs but because they don’t submit complex paperwork while they’re eligible for Medicaid, or because they don’t (or can’t) meet new requirements despite the threat that they will lose their health coverage. And even more enrollees will likely lose coverage because they work but don’t work the required number of hours each month. There’s no reason to expect that people losing Medicaid for these reasons can replace it with other coverage; rather, the large majority of them will likely become uninsured.

-

Even under optimistic assumptions, few enrollees will leave Medicaid because the new requirements prompt them to find jobs and, in turn, affordable health insurance. Research on work requirements in other federal programs finds little evidence that they produce sizeable and lasting increases in employment or income. And work requirements and other eligibility restrictions in Medicaid may have even more disappointing results. One reason is that taking away health coverage and access to care will likely make it harder for some enrollees to look for work or maintain stable employment. Another is that the recent restrictions come with no new funding for job training, child care, or other work supports.

Moreover, even if some enrollees find jobs, they will likely be mostly low-wage jobs. Such jobs won’t likely boost enrollees’ incomes enough to enable them to shift from Medicaid to subsidized individual market coverage, and the large majority of those jobs don’t offer affordable health insurance. For example, among workers in the bottom fourth of the wage distribution, only 37 percent are offered medical coverage, and less than a quarter actually get coverage, presumably in large part because required premium contributions are often higher than they can afford.

As noted above, Kaiser found that, if Medicaid work requirements were imposed nationwide, 1.4 to 4.0 million people would leave Medicaid because they couldn’t meet the requirements or failed to submit required paperwork – and would likely become uninsured. In contrast, even if the policy had employment effects comparable to work requirements in other programs, and if 37 percent of those finding jobs obtained health insurance, well under 100,000 people would be expected to leave Medicaid because they obtained job-based coverage.

-

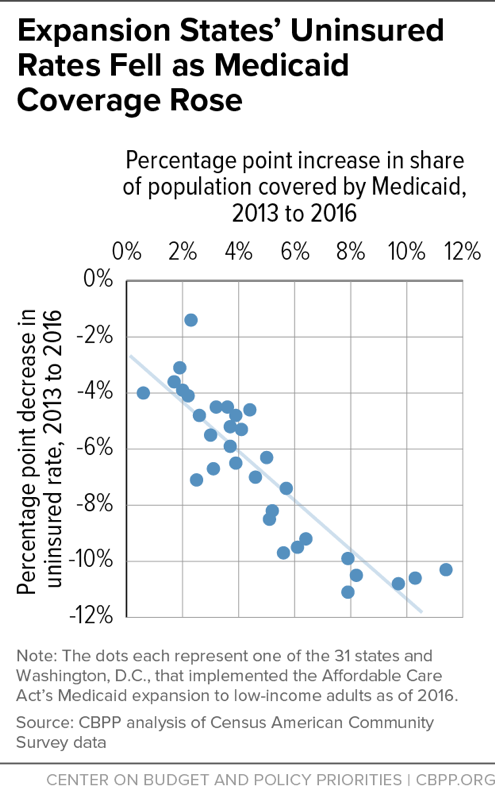

Other evidence also shows that Medicaid enrollees mostly lack other options for coverage. Consider the impact of past changes in Medicaid eligibility. After the ACA gave states the option to expand their Medicaid programs to more low-income adults, the share of this group covered by Medicaid rose and the share uninsured fell by similar amounts (see graph) — with little or no offsetting decline in employer coverage. That suggests that the large majority of Medicaid expansion enrollees would have been uninsured if not for the expansion, contradicting claims that the expansion would “crowd out” private coverage (that is, cause people to shift from private coverage to Medicaid). That, in turn, suggests that most adult enrollees who lose Medicaid eligibility due to waivers will become uninsured — as many of them were before the expansion — rather than gain coverage from other sources. Similarly, past eligibility restrictions and administrative barriers in Medicaid have caused many people to become uninsured.