Holding up the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program as a model, some state and federal policymakers are considering — or have already imposed — policies that would take away SNAP (formerly food stamp) benefits, Medicaid coverage, or housing assistance from people who don’t work or engage in work-related activities for a specified number of hours each month. A review of the many studies on families whose TANF monthly direct financial support was reduced or taken away due to work requirements suggests that these policies would harm millions of individuals and families, most of whom face significant obstacles to employment, while producing few lasting gains in employment.

Research on TANF suggests that policies to take away SNAP, Medicaid, and housing assistance from individuals who are not working or participating in work activities will hurt, not help, the individuals most in need of assistance.

More than 2 million families have lost all of their TANF direct financial support because of work-oriented sanctions and many more have had their support reduced since July 1997, when the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) began collecting these data. A much greater number of individuals and families could lose Medicaid or SNAP benefits if such policies were applied to those much larger programs. (About 4.4 million families received direct financial assistance in 1996, the year when the TANF block grant was created; now only 1.3 million families receive such assistance.)

The TANF studies, most of them conducted in the program’s early years, are primarily descriptive, using surveys of recipients and administrative data to compare the characteristics and circumstances of recipients who have been sanctioned (that is, had their benefits reduced or eliminated) for failure to meet work requirements with other recipients. While the studies used different research methods and examined states with very different approaches to work requirements, their findings are remarkably consistent:

- States often apply work requirements inappropriately. Agencies that administer public benefit programs are ill-equipped to identify people who should not be subject to work requirements. Multiple studies have uncovered problems in the process by which states sanction families for failure to meet work requirements. A study by Tennessee’s TANF agency, for example, found that about 30 percent of sanctions in the state were imposed in error.[1]

Studies also show that many parents who lose benefits due to work requirements have significant employment barriers, including many that would qualify them for exemptions under most states’ TANF work rules. Those losing benefits are more likely than other TANF parents to have physical, mental health, or substance use issues; to be fleeing domestic violence; to have low levels of education and limited work experience; or to face significant logistical challenges, such as lack of access to or funds to pay for child care and transportation.[2]

States’ application of work requirements has also exacerbated racial inequities. Nearly every study comparing the race and ethnicity of sanctioned and non-sanctioned TANF recipients finds that African Americans are significantly more likely to be sanctioned than their white counterparts.[3]

- Work requirements have contributed to the near elimination of the cash safety net in many states, without generating lasting gains in work. As noted, more than 2 million TANF cases have been closed due to a work-oriented sanction since July 1997, and even more families have had their cash benefits reduced. Also, 20 states require families to comply with job-related requirements before approving their application for cash assistance. As a result of policies ending and denying benefits based on work requirements, along with other restrictive policies such as time limits, substantially fewer families receive cash assistance to help meet their basic needs today than before TANF’s creation. For every 100 families with children in poverty, only 23 receive cash benefits from TANF — down from 68 families in 1997, when TANF was fully implemented.[4]

Contrary to claims that reducing or eliminating benefits for not meeting a work requirement will compel parents to find work, studies consistently find lower employment rates among parents whose TANF cases were closed due to a work-oriented sanction than among those who left TANF for other reasons. In Illinois, for example, work-sanctioned parents were 44 percent less likely to be employed than those who were not sanctioned, even after controlling for previous work experience and other characteristics associated with employment.[5]

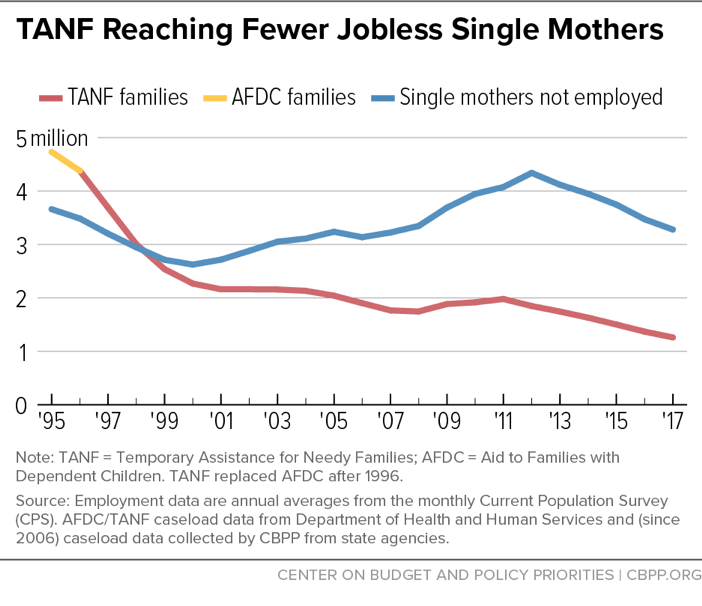

As it has become harder for single mothers to get direct financial assistance when they are not working, the number with neither jobs nor TANF has grown substantially over time. In 1995, the number of families receiving cash assistance in an average month exceeded the number of jobless single mothers by about a million. By 2016, the number of families receiving cash assistance in an average month was roughly 2 million below the number of jobless single mothers. (See Figure 1.)

- Many families losing TANF cash assistance experience hardships. Families living on the edge often have few or no assets to lean on in difficult times; when their limited resources are taken away, they struggle to make ends meet, and some are unable to avoid a downward spiral, as studies show. A Michigan study, for example, found that 21 percent of sanctioned families (compared to 9 percent of non-sanctioned families) had their utilities shut off and that 34 percent of sanctioned families (compared to 14 percent of non-sanctioned families) had resorted to activities such as pawning, stealing food, searching in trash cans, or begging.[6]

The few studies examining sanctions’ impact on children find that they increase the chances of hardship and disruptions that can reduce children’s chances of success over the long term. For example, a six-city study of TANF recipients seeking emergency room treatment for a child found that children in sanctioned families who had their direct financial assistance payments reduced or eliminated because of a sanction were 30 percent likelier to have been hospitalized previously, 50 percent likelier to be food insecure, and 90 percent likelier to be admitted to the hospital at the time of the emergency room visit, relative to children in non-sanctioned families.[7]

In short, research on TANF suggests that policies to take away SNAP, Medicaid, and housing assistance from individuals who are not working or participating in work activities will hurt, not help, the individuals most in need of assistance.

Agencies are ill-equipped to determine who should not face work requirements. Federal law requires states to cut families’ cash assistance benefits if they don’t meet the TANF work requirements, but states are free to decide the details of such policies, including when — and to whom — they should apply, their magnitude, and their duration. These penalties, known as partial and full family sanctions, have played a central role in TANF’s implementation and have gotten harsher over time. When a full family sanction is imposed, the family loses all of their direct financial assistance, which means they may be left with no regular cash income to pay their rent or utilities or buy necessities such as toothpaste, soap, laundry detergent, and clothes. When a partial sanction is imposed, a family’s direct financial assistance is reduced, leaving them with less money for these basics.

In all states except New York, California, and the District of Columbia, families can immediately or eventually lose their entire cash grant due to work requirements. In addition, 20 states require families to demonstrate compliance with specified job search or job readiness activities before approving their application for cash assistance.

The responsibility for determining which families should be subject to work requirements lies with the states and county or local assistance offices. Research shows that these processes are fraught with problems. Staff tasked with conducting assessments, lacking both time and adequate training, often fail to identify circumstances that would exempt parents from the work requirements. Also, recipients are much more likely to be sanctioned in conservative localities than in more progressive ones due to the substantial amount of local discretion, one study found.[8] In addition, many recipients report that they don’t understand work requirements and what they must do to claim an exemption; many families with significant employment barriers thus lose part or all of their benefits even if they shouldn’t be subject to a work requirement.

Multiple studies have uncovered problems in the sanction process. A study by Tennessee’s TANF agency, for example, found that about 30 percent of sanctions in the state were imposed in error. These errors can result from clerical errors, miscommunication, or failure to receive notices, for example. A study of sanctions in seven states found that case managers with large caseloads typically impose a sanction without any effort to contact the parent to inquire why they are not working or participating in work activities.[9] And when staff in Los Angeles visited the homes of families facing a benefit cut due to a work requirement, they found that a substantial share were already working or had an acceptable reason (known in TANF as “good cause”) for not participating.[10] In most states, families can be sanctioned if they miss a single appointment.

Many parents losing assistance face significant employment barriers. Families whose TANF cash benefits have been cut or their cases closed due to work requirements are among those who face the most significant barriers to employment and need the most help finding and maintaining employment. Studies consistently show that parents who have limited work experience and/or low education levels, physical or mental health issues, are fleeing domestic violence, or lack child care or transportation are among those likeliest to lose benefits for not meeting work requirements. For example:

- A study of a sample of Michigan women found that recipients who had not completed high school were twice as likely to be sanctioned as those who had completed high school. Sanctioned recipients also were more likely than non-sanctioned recipients to be a victim of domestic violence and to lack a car or a driver’s license.[11]

- A longitudinal study in Maryland found that about a fifth of parents who had their cases closed due to a work sanction applied for Supplemental Security Income benefits after their TANF case closed, suggesting that they had a disability that significantly limited their ability to work and that they expected to last for an extended period.[12]

- A comparison of sanctioned and non-sanctioned TANF recipients in Boston, Chicago, and San Antonio found sanctioned recipients were less likely than other TANF recipients to have a high school degree or its equivalent, a working telephone at home, or a car. They were more likely to report being in fair or poor health or to have a substance use issue. They also had less work experience, lived in neighborhoods with undesirable qualities (such as abandoned houses, assaults and muggings, gangs, and open drug dealing), and reported living in housing of poor quality.[13]

- In Illinois, parents who had ever been sanctioned were significantly less likely than those never sanctioned to have a high school diploma or its equivalent and more likely to have limited recent work experience. They also were significantly more likely to be dealing with a physical or mental health issue, to have been arrested multiple times, and to have experienced a child care issue. In South Carolina, parents ever sanctioned were significantly more likely to have a physical health problem, show signs of a learning disability, and have a family member or friend with a health care issue or special need.[14]

- Interviews conducted over three years (1999–2001) with 356 California TANF participants found that those who had a mental health diagnosis were about 13 percent more likely to leave the program for reasons related to non-compliance with work requirements than those who did not.[15] A second California study found that recipients without a car were roughly 1.5 times more likely to incur sanctions than recipients who owned a car.[16]

Studies find racial bias in imposing sanctions. Nearly every study comparing the race and ethnicity of sanctioned and non-sanctioned TANF recipients finds that African American recipients are significantly more likely to be sanctioned than their white counterparts. Researchers using fictitious case examples to examine racial bias found that caseworkers were much more likely to sanction African American mothers with previous sanctions than they were to sanction white women with previous sanctions; the case examples varied only on two dimensions: race and whether recipients had been sanctioned.[17] A study that examined state policy choices found that state TANF policy decisions are significantly related to race: states with larger African American populations, all else equal, have less generous and more restrictive TANF policies.[18]

Studies examining a broad range of states and localities find higher rates of sanctioning among African American recipients:

- In a Michigan study, race was one of the strongest predictors of being sanctioned. African American recipients were 1.73 times more likely to be sanctioned than whites.[19]

- A Florida study found that among families receiving assistance for longer periods, African Americans were more likely to be sanctioned than whites. After receiving assistance for nine months, African Americans were 22 to 35 percent more likely to be sanctioned than whites, depending on the county where they lived.[20]

- A Wisconsin study found that African American and Hispanic families that entered TANF in its first year of implementation (1997) were significantly more likely to be sanctioned than white families. This occurred, in part, because African American and Hispanic participants’ lower levels of education and limited work experience — circumstances associated with structural racism — led them to receive TANF longer, which created more opportunities for sanctions.[21]

- A New Jersey study found that among TANF recipients entering the program between July 2000 and June 2001, 36 percent of African American recipients had their TANF grants reduced and 16 percent had their grant eliminated due to a work-related sanction; the comparable figures for white recipients were 27 percent and 10 percent, respectively.[22]

In 2002, the ACLU and the Milwaukee branch of the NAACP filed a complaint with HHS’ Office for Civil Rights claiming racial and disability discrimination in the application of sanctions against TANF participants. The claim was based on data from the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development showing a consistent pattern of racial and ethnic discrepancies in TANF sanctions. Statewide, 42 percent of African American participants and 45 percent of Hispanic participants were sanctioned, compared to just 24 percent of white participants.[23] Though the state did not admit to any violations to the Civil Rights Act, it entered into an agreement with the Office for Civil Rights requiring staff training, improved assessment screening tools and procedures, reasonable accommodations for clients’ needs, and new procedures to ensure that the agency considers disabilities and barriers before taking adverse action.

The cash safety net has nearly disappeared in some states. Policies that deny, reduce, or take away direct financial assistance because of work requirements have left many families with little or no cash to meet their basic needs. Half to two-thirds of families receiving assistance have their cash assistance grants reduced or eliminated due to a work-oriented sanction, studies that follow families over time show. More than 2 million TANF cases have been closed due to a work-oriented sanction since July 1997, when HHS began reporting these data. (The number of cases closed due to sanctions likely is higher than these data suggest because states do not always report reasons for case closure accurately.) An even greater number of families have had their cash benefits reduced. In TANF’s early years, five times as many families had their grants reduced than had their cases closed in an average month, the Government Accountability Office estimated.[24] In the three years after Texas shifted its sanction policy from reducing a family’s grant to eliminating it altogether, its caseload fell by almost half, from 119,000 to 61,000 families.[25]

While national data aren’t available on how many families’ TANF applications are denied due to work requirements, data from a few state studies suggest the number is substantial. A study of application processes in TANF’s early years found that in the study site with the most stringent applicant job search requirement (Cook County, Illinois), 62 percent of the study sample either decided not to apply for TANF or didn’t complete the application process — twice the share in most of the other sites, which had no applicant job search requirements at the time.[26] When Georgia changed its practices to impose more stringent work requirements as a condition of eligibility, the share of applications approved plummeted from about 50 percent to 22 percent.[27]

As a result of work-oriented sanctions, applicant job search requirements, and other policies (such as time limits) that take families’ cash benefits away even though they still need assistance, substantially fewer families receive direct financial assistance to help meet their basic needs today than before TANF’s creation. For every 100 families with children in poverty, only 23 receive cash benefits from TANF, down from 68 families in 1997, when TANF was fully implemented. If this “TANF-to-poverty ratio” were the same today as in 1997, 2.6 million more families would be receiving TANF in an average month. In a growing number of states, TANF has all but disappeared: in 16 states, 10 or fewer families receive TANF cash benefits for every 100 families in poverty. (See Figure 2.)

Most TANF recipients who lose benefits due to sanctions don’t find steady employment. The rationale for reducing or eliminating benefits for not meeting a work requirement is that this will compel parents to find work. Evidence suggests that work requirements (along with other policy changes that accompanied TANF’s implementation) contributed to a modest increase in employment during the late 1990s, but that work often was not steady,[28] a pattern reflected in recent studies as well.

Also, as it has become harder for single mothers to get direct financial assistance when they are not working, the number with neither jobs nor TANF has grown substantially over time. In 1995, the number of families receiving cash assistance in an average month exceeded the number of jobless single mothers by about a million. By 2016, the number of families receiving cash assistance in an average month was roughly 2 million below the number of jobless single mothers.

Studies consistently find lower employment rates among TANF “leavers” whose cases were closed due to a work-oriented sanction than among families that left TANF for other reasons.

- In Illinois, work-sanctioned parents were 44 percent less likely to be employed than those who were not sanctioned, even after controlling for previous work experience and other characteristics associated with employment.[29]

- In Arizona, 40 percent of sanctioned leavers were working in the first quarter after exit, compared to 55 percent of non-sanctioned leavers.[30]

- In Maryland, 6 months after exit, 38 percent of sanctioned leavers were employed compared to 58 percent of non-sanctioned leavers.[31]

- In Wisconsin, TANF recipients who experienced harsher sanctions were five times more likely to have neither work nor cash assistance than recipients who were not sanctioned. They also were more than twice as likely as non-sanctioned leavers to earn less than they would have received in cash assistance.[32]

A recent study of the employment experiences of TANF recipients in Kansas who had their cases closed because of a work sanction shows how unstable work is for sanctioned recipients. The majority of recipients who left TANF because of a work sanction worked both before and after exiting TANF; over that period, including the exit quarter, 84 percent worked — and they were just as likely to work before exiting TANF as after. Their work was very unsteady, however, with only about a quarter working between seven and nine quarters over the study period. In any given quarter the share working never reached 50 percent and increased only slightly after they exited TANF, from 44 to 49 percent. Their annual incomes were also extremely low; only 24 percent had annual earnings above deep poverty (at or above 50 percent of the federal poverty line) in the first year after their TANF case was closed.[33]

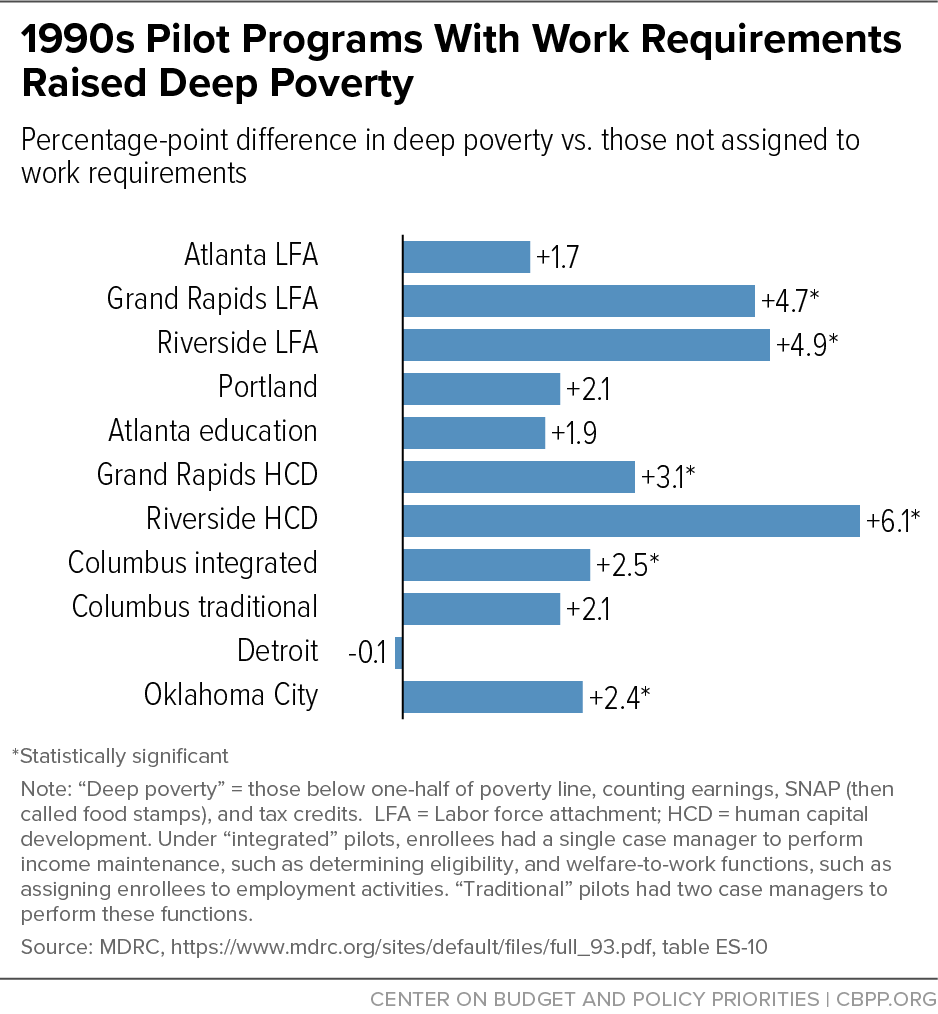

Work requirements for cash assistance fueled rise in deep poverty. Rigid work requirements in government assistance programs have a well-established record of fueling deep poverty.[34] The largest federally funded study of work-requirement pilot programs for cash assistance recipients in the 1990s examined 11 programs — local forerunners of the work requirements in the 1996 welfare law. Most of them raised employment rates somewhat in the short term. Yet, not all recipients found work and many families were pushed off the program or had their benefits reduced due to work-related sanctions. As a result, deep poverty rates rose by a statistically significant amount in six of the 11 programs — and fell significantly in none — relative to randomly assigned control groups.

The findings reflect the most rigorous form of evidence: a comparison between program participants and control groups randomly assigned to more traditional welfare programs, which reveals the impact of the pilot programs distinct from other factors (such as the shifting economy). To measure income carefully, the evaluators used agencies’ administrative benefits data and employers’ payroll records rather than individuals’ recollections on a survey, which can be imprecise.

The findings also showed that work requirements can raise deep poverty even while, in some cases, reducing the share of participants below the poverty line. One program in particular (Riverside California’s labor force attachment program) simultaneously increased the deep poverty rate significantly (by 4.9 percentage points) and lowered the poverty rate significantly (by 2.4 percentage points). In seven of the other ten pilot programs, deep poverty rose while poverty fell, although not by statistically significant amounts in both cases.

Averaging across all sites, the 11 programs lowered poverty by an average of 2.1 percentage points but raised deep poverty by 2.9 percentage points. This diverging pattern suggests that the programs raised the stakes for poor families, pushing some to find more employment and perhaps climb above the poverty line, while letting other families — or the same families in unluckier months — fall into deeper financial hardship when they failed to find work or earnings were especially low. Consistent with that interpretation, the programs tended to increase the share of parents with jobs in any given three-month period but also the share with neither earnings nor assistance.

Importantly, the improvements in employment and traditional poverty did not last. The results above reflect the programs’ second year. A follow-up study found that, over five years, employment gains weakened and, “because the earnings gains were offset by reductions in welfare benefits,” the 11 programs did not yield “systematically greater income or reduced poverty for welfare recipients” and “did not generally improve the economic well-being of the welfare recipients.”[35] (Furthermore, it is unclear whether TANF’s impacts on poverty, if measured in the same rigorous way, would be equally positive, even in the short term. The pilot programs preceded the implementation of TANF and their work rules were generally not as harsh as TANF’s; for example, they excluded more families with young children than TANF did, exempted recipients with substantial employment barriers, and required fewer hours of participation per week.)

Evaluators did not track the pilot programs’ impacts on deep poverty over the longer period. Nationwide data, however, suggest that the work requirements and other policies of the 1990s erected lasting barriers to cash assistance for families in need. More than 3 million fewer families received cash assistance in 2017 than in 1995, a decline of two-thirds, even though the total number of single parents without jobs was roughly the same in both years. To the degree that families still face heightened barriers to accessing assistance when they need it, the overhaul in cash assistance policies is likely still pushing upward on deep poverty.[36]

TANF recipients losing cash assistance experience multiple hardships. For families living on the edge, cash is crucial to providing stability and preventing a downward spiral. They often have few or no assets to lean on in difficult times and need cash for a variety of basic needs: rent and utilities, clothes, personal care items (such as toothpaste, laundry detergent, and diapers), and gas or bus fare, among other things. When their limited resources are taken away, they struggle to make ends meet and some are unable to avoid a downward spiral, as studies examining sanctioned families show.

- In Michigan, researchers found that 21 percent of sanctioned families (compared to 9 percent of non-sanctioned families) had their utilities shut off.[37]

- A Washington State study using predictive modeling to identify the factors likeliest to cause a new spell of homelessness for TANF parents found that sanctioned recipients were about 20 percent more likely than non-sanctioned parents to begin a new spell of homelessness in the next month.[38]

- In Illinois, researchers found that sanctioned families were three times more likely to report food hardship than those not sanctioned, after controlling for demographic and other factors.[39]

- In the previously mentioned study of families in Boston, Chicago, and San Antonio, sanctioned families were twice as likely as non-sanctioned families to say they lacked adequate food and five times as likely to borrow money to pay a bill.[40]

- A study comparing the circumstances of sanctioned and non-sanctioned food pantry recipients in an upstate New York in 1997 found that recipients who had been sanctioned experienced greater hardship than those who had not been sanctioned. A third of those sanctioned indicated they had to move because they couldn’t pay rent, compared to 14 percent of those not sanctioned. Sanctioned recipients also reported higher rates of difficulty paying their bills (83 versus 60 percent), paying their rent (67 versus 46 percent), and paying for health care for themselves (67 versus 28 percent).[41]

- A study conducted in 20 cities in 15 states of mothers who had received TANF in the prior 12 months found that 42 percent of those who had been sanctioned reported one or more of the following four hardships: maternal or child hunger, eviction or homelessness, utility shutoff, and inability to receive medical care due to cost. The comparable figure for non-sanctioned mothers was 27 percent.[42]

Children in sanctioned families are likelier to experience harm. Families with children often turn to TANF cash assistance when a change in their circumstances places them in a particularly vulnerable situation, such as losing a job, giving birth, fleeing domestic violence, or experiencing a serious medical or mental health issue. Studies have found that income support programs not only help families in the short term but also can help poor children succeed over the long term — that is, enable them to do better (and go further) in school, earn more as adults, and even live longer.[43] The reverse is also true: when benefits are taken away, the negative short-term impacts can reduce children’s changes of success in the long term. Only a few studies have examined the consequences of sanctions on children, but they find that children in sanctioned families are more likely to experience hardship and disruptions that can have long-term implications.

- A study of current and former TANF recipients seeking emergency room treatment for a child in six cities found that children in sanctioned families were 30 percent likelier to have been hospitalized previously, 50 percent likelier to be food insecure, and 90 percent likelier to be admitted to the hospital at the time of the emergency room visit, relative to children in non-sanctioned families.[44]

- In a study of sanctioned families in Delaware, researchers found that sanctions resulted in a small but statistically significant increase in child neglect. The authors concluded that these findings were related to parents’ difficulties in meeting their responsibilities for their children as they adjusted to life without cash assistance.[45]

- A Minnesota study found that sanctioned families had substantial difficulty supporting regular school attendance or preventing frequent disruptions in enrollment, such as moving to a new school. Three-quarters of high school students in sanctioned families experienced a school disruption, as did 23 percent of middle school students and 42 percent of elementary school students. For elementary students, attendance worsened markedly as the number of sanctions increased.[46]

- In the previously mentioned New York food pantry study, 60 percent of children in sanctioned families changed schools compared to 41 percent in non-sanctioned families.[47]

These study findings raise serious concerns. Parents facing the most significant barriers have been sanctioned due to work requirements, even though nearly every state has a process to exempt some of them. Recipients often are reluctant to reveal the challenges they face to a staff person they have never met, and staff often carry high caseloads, leaving them with little time to accurately assess recipients’ circumstances. Work-related sanctions have imposed hardships on large numbers of vulnerable families, eliminating not only their cash benefits to meet basic needs but also access to the very services that could improve their employment prospects over the long term.

The findings suggest that even if a state only intends to impose work requirements on “work able” individuals, substantial numbers of SNAP, Medicaid, or housing assistance recipients who face personal or family challenges would likely fall through the cracks and have their benefits reduced or taken away. These programs lack the resources and employment infrastructure to adequately identify recipients who are not “work able.” TANF has far more resources dedicated to these tasks for a significantly smaller number of people, yet many recipients with significant employment barriers have had their benefits reduced or eliminated because of work-oriented sanctions.

Government certainly has a role to play in creating pathways to work for individuals who face significant employment barriers, but taking their food, health care, and housing assistance away is not the path forward.