BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Medicaid is key to building a system of care in which people with substance use disorders (SUD) get the care they need, regardless of income or race, as our new paper explains. And the recently enacted American Rescue Plan Act gives states more resources to make Medicaid’s role in funding an equitable SUD system of care even stronger.

Medicaid can cover a range of SUD treatment and recovery supports, but most states fail to cover the full range, and 14 have yet to implement the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion making the program’s coverage available to low-income adults. This has hindered states from responding to the substance use crisis and protecting access to SUD care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Drug overdose deaths rose dramatically over the last 20 years: from fewer than 20,000 in 2000 to an all-time high of over 71,000 in 2019, and likely even higher in 2020, preliminary data suggest. Yet before the pandemic, fewer than 13 percent of the 21 million-plus people who needed SUD treatment received any.

Some experts, including officials with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suspect that overdose deaths are accelerating because the disruptions in daily life, stress, and severe economic hardship that the pandemic has caused may be exacerbating substance use and reducing access to treatment and recovery supports. And while more research is needed, the spike in overdose deaths appears to be disproportionately harming Black people in at least some communities. In the three months after the pandemic hit Philadelphia, opioid overdose deaths rose by more than 50 precent among Black residents but remained steady or declined among white residents, a new study found.

Among its provisions boosting Medicaid, the American Rescue Plan Act includes one year of enhanced federal funding for home- and community-based services (HCBS), which states can use to boost such services targeting SUDs, and a strong financial incentive for states that haven’t expanded Medicaid to quickly do so. States can use these provisions to shore up access to SUD services during the pandemic and build a more equitable system for the future. For instance, they can extend coverage to more people with low incomes and cover a full continuum of SUD services, compared to the patchwork that most states currently provide.

States must use the one-year, 10-percentage-point increase in federal matching funds that the Act provides for HCBS to supplement rather than supplant their current spending on these services. This means states must enhance, expand, or strengthen HCBS, the benefits of which can extend long term. States can increase provider reimbursement rates, expand their HCBS capacity, or cover additional community-based SUD services, among other program improvements that would benefit people with SUDs.

Community-based SUD providers have been hit hard by heavy financial losses and new expenses during the pandemic as they scrambled to increase telehealth services and provide personal protective equipment to staff and the people they serve. This was on top of already low reimbursement rates for public and private behavioral health coverage. The situation has forced providers to make tough decisions to lay off staff, delay care, and even turn away patients or close programs. Raising provider payment rates and covering additional community-based services — including through section 1915(i) state plan amendments that don’t require waivers from federal Medicaid law — can help providers of SUD services and other HCBS continue delivering care during the pandemic and strengthen access to care for years to come.

In addition, the Act makes Medicaid expansion — already a great financial deal for states — even better for the 14 that haven’t yet implemented expansion. States that expand will get a two-year, 5-percentage-point increase in the federal share of their Medicaid costs (known as the federal medical assistance percentage or FMAP) for all non-expansion enrollees, who account for most of a state’s Medicaid enrollment and costs.

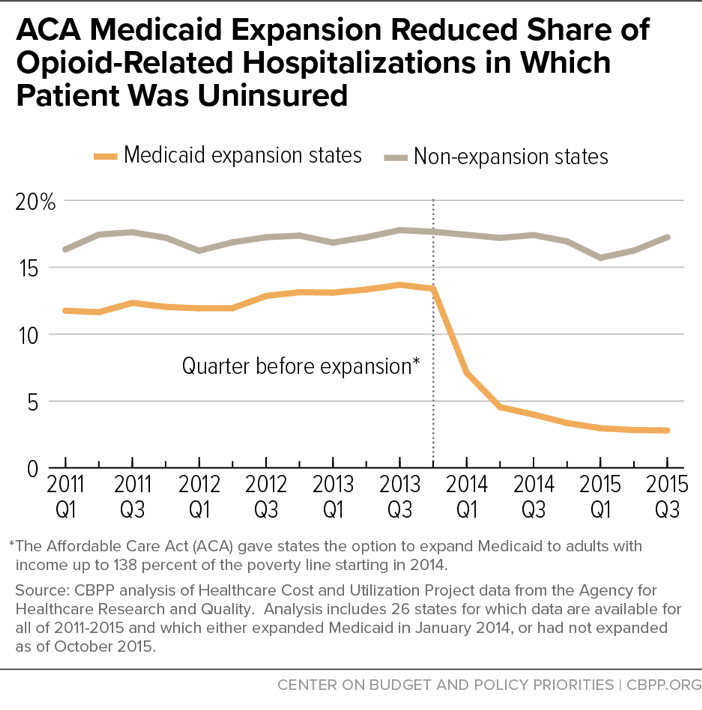

Expansion has been a powerful tool for improving coverage and access to care for low-income enrollees with SUDs. For example, the uninsured rate among people with opioid-related hospitalizations fell dramatically in states that expanded, from 13.4 percent in 2013 (the year before expansion took effect) to just 2.9 percent two years later. (See chart.) And additional studies find that Medicaid expansion significantly increased SUD treatment access for Medicaid beneficiaries.

Expansion would also help narrow racial inequities in health coverage, including for SUD services; nearly 60 percent of uninsured people who could gain coverage in remaining non-expansion states are people of color. And the big funding boost the Act provides expanding states would enable them to enhance SUD care. They could cover more recovery supports, such as peer support, supported employment, and tenancy support services. States could also fund higher reimbursement rates and technical assistance to help more SUD providers participate in the Medicaid program, helping ensure that enough qualified providers serve new Medicaid enrollees.