BEYOND THE NUMBERS

June 15, 2020: We have updated our estimate of projected state shortfalls. Please see this paper for our new estimate.

As economic projections worsen, so do the likely state budget shortfalls from COVID-19’s economic fallout. We now project shortfalls of $765 billion over three years, based on the new projections from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) of yesterday and Goldman Sachs of last week. The new shortfall figure, significantly higher than our estimate based on economic projections of three weeks ago, makes it even more urgent that the President and Congress enact more fiscal relief and maintain it as long as economic conditions warrant.

CBO now projects that unemployment will peak at 15.8 percent in the third quarter of this year (July-September), fall to a still-high 11.5 percent by the last quarter, and remain at an elevated 8.6 percent at the end of 2021. Goldman’s new projection estimates that unemployment will peak at an astonishing 25 percent this quarter and still remain at 8.2 percent at the end of 2021. These CBO and Goldman estimates, considerably more pessimistic than their estimates of early April, account for the aid that Washington has already enacted for businesses, individuals, and state and local governments. Goldman’s projections also assume that policymakers will provide additional fiscal relief.

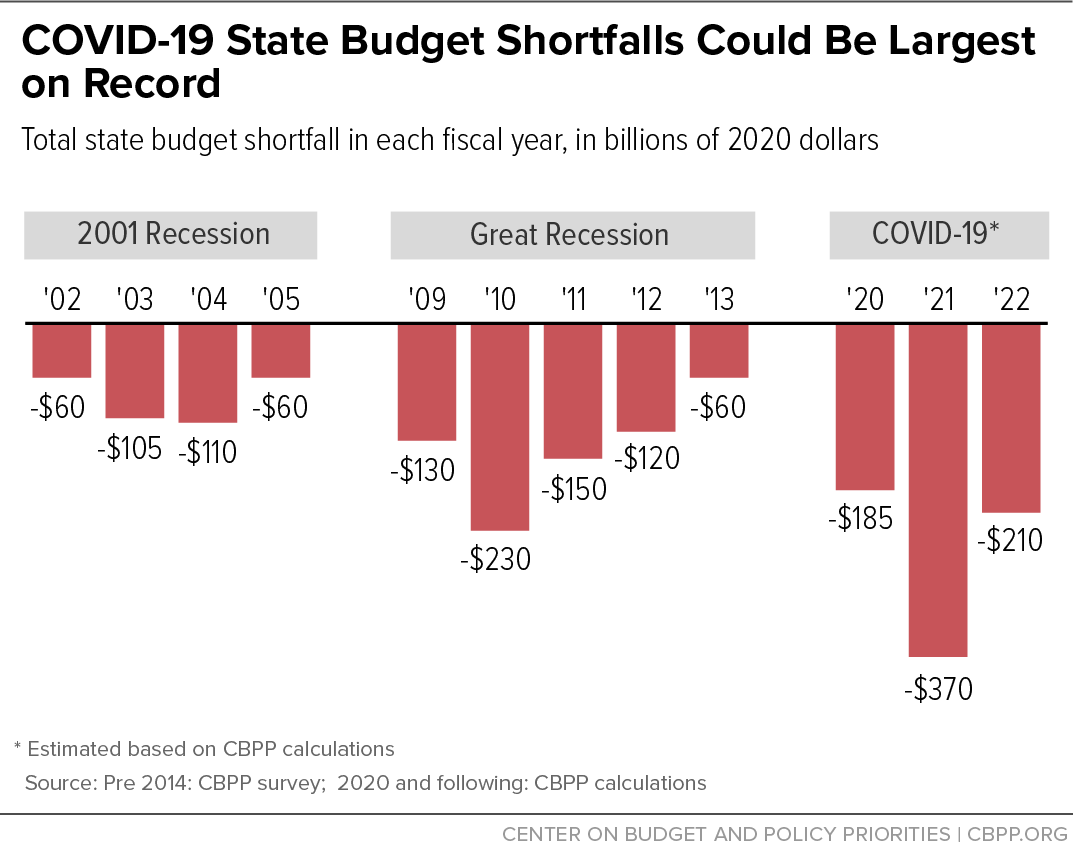

Our projection of $765 billion in shortfalls over state fiscal years 2020-22 — much deeper than in the Great Recession of about a decade ago (see chart) — is based on both the historical relationship between unemployment and state revenues and on the average between the latest CBO and Goldman projections. It covers state budget shortfalls only, not the additional shortfalls that local governments, territories, and tribes face.

Federal aid that policymakers provided in earlier COVID-19 packages isn’t nearly enough. Only about $65 billion is readily available to narrow state budget shortfalls. Treasury Department guidance now says that states may use some of the aid in the CARES Act of March to cover payroll costs for public safety and public health workers, but it’s unclear how much of state shortfalls that might cover; existing aid likely won’t cover much more than $100 billion of state shortfalls, leaving nearly $665 billion unaddressed. States hold $75 billion in their rainy day funds, a historically high amount but far too little to meet the unprecedented challenge they face. And, even if states use all of it to cover their shortfalls, that still leaves them about $600 billion short.

States must balance their budgets every year, even in recessions. Without substantial federal help during this crisis, they very likely will deeply cut areas such as education and health care, lay off teachers and other workers in large numbers, and cancel contracts with many businesses. (States and localities furloughed or laid off nearly a million workers in April alone.) That would worsen the recession, delay the recovery, and further harm families and communities. State and local cuts in health care also could shortchange coronavirus response efforts. The large shortfalls could lead states and localities to raise taxes and fees as well.

The coronavirus relief bill that the House passed on May 15, the Heroes Act, includes substantial state and local fiscal relief, both by providing flexible grant aid and by strengthening and extending the temporary increase in the federal share of Medicaid costs in the Families First Act of March — a particularly effective and efficient form of aid that alleviates state budget pressures and protects health coverage. States will need aid of this magnitude to avoid extensive layoffs of teachers, health care workers, and first responders, which would further weaken an already weak economy.