BEYOND THE NUMBERS

May 21, 2020: We have updated our estimate of projected state shortfalls. Please see this post for our new estimate.

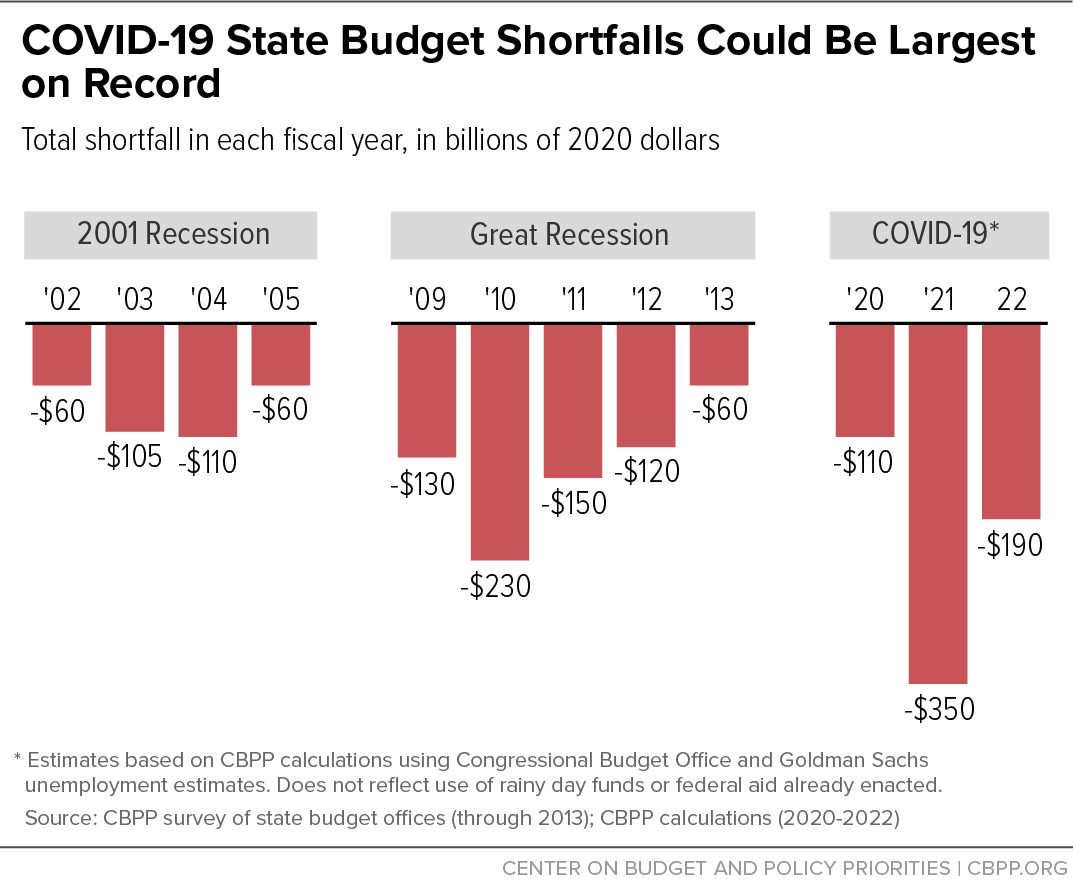

State budget shortfalls from COVID-19’s economic fallout could total $650 billion over three years, we estimate based on new economic projections from the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and updated projections from Goldman Sachs. The new figures — significantly higher than estimates we recently issued based on economic projections of a month ago — increase the urgency that policymakers enact additional federal fiscal relief and continue it as long as economic conditions warrant.

CBO now projects that unemployment will average 15 percent for the next six months and then fall only slowly. It will still be 9.5 percent — just short of its 10 percent peak in the Great Recession — at the end of 2021. These CBO estimates take into account the federal aid already enacted for businesses, individuals, and state and local governments.

That’s considerably more pessimistic than CBO’s April 2 projections and Goldman Sachs’ projections of March 31 and April 15. A paper we recently issued on state fiscal conditions used Goldman’s March 31 projections and the historical relationship between unemployment and state revenues to estimate that states would face $500 billion in state shortfalls in fiscal years 2020 through 2022. Averaging CBO’s new projections with the latest Goldman estimates produces shortfalls totaling $650 billion, substantially deeper than during the Great Recession. (See chart.) This estimate is for state budget shortfalls only; it does not reflect the additional shortfalls that local governments, territories, and tribes face.

Federal aid provided to date will help cover some of these shortfalls but it is not nearly enough. Only about $65 billion of the aid provided in earlier COVID-19 packages is readily available to narrow these shortfalls. Using that aid and the $75 billion that states have in rainy day funds would leave states with about $510 billion in unaddressed shortfalls.

States must balance their budgets every year, even in recessions. Without substantial federal help, they very likely will deeply cut areas such as education and health care, lay off teachers and other workers, and cancel contracts with businesses. That would worsen the recession, delay recovery, and hurt families and communities. The health care cuts could also shortchange coronavirus response efforts. The large budget shortfalls could lead states and localities to raise taxes and fees, as well.

No one knows precisely how this unprecedented crisis will affect the economy, but underestimating its effects would have grave consequences for state budgets and thus for families, businesses, and communities. If federal aid ends too soon, states will have to depend much more heavily on spending cuts and tax increases to balance their budgets. Accordingly, the next relief package should include a large new round of fiscal relief, using “triggers” based on job market conditions to determine when assistance phases up or phases out.

A national trigger would ensure that relief measures continue nationwide as long as needed but no longer. Since the recovery may occur at different rates across the country, additional state-specific triggers could provide longer-lasting help in states facing greater challenges after nationwide relief triggers off.

State relief can include these triggers whether it takes the form of a higher federal Medicaid matching rate to cover Medicaid’s costs — a particularly efficient method — grants to states, or (as is most likely and most efficacious) a combination of the two. Policymakers should also link measures such as expanded jobless benefits and increased SNAP (food stamp) benefits to job market indicators, so such measures continue as long as they’re needed.

The Great Recession shows the potential problems from not tying relief measures to economic conditions — and letting them end too early. Although unemployment remained quite high in the years after the economy hit bottom and the recession technically ended, policymakers let critical relief measures expire prematurely, which slowed the recovery materially and increased hardship.