BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Some state policymakers continue to propose linking Medicaid coverage to work or work-search requirements despite recent statements from Administration officials that these requirements don’t belong in Medicaid. As we’ve explained, work requirements conflict with Medicaid’s purpose of providing health care to people who can’t otherwise afford it. In fact, work isn’t a requirement in any other health coverage program — individuals who get tax credits to help buy health coverage through the marketplace don’t have to work, nor do people who enroll in health coverage that their spouse’s employer offers.

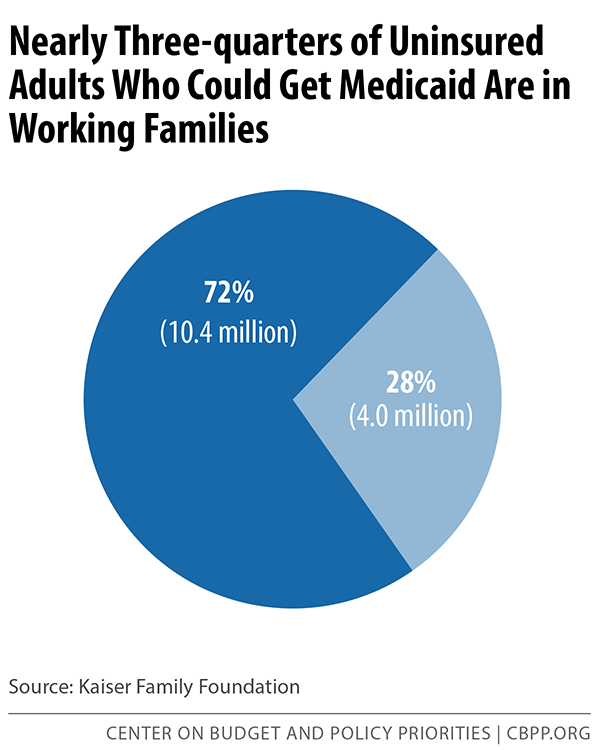

Along with conflicting with Medicaid’s basic purpose, work or work-search requirements aren’t necessary. Nearly three-quarters of uninsured adults who are eligible for Medicaid coverage live in a family with at least one full-time or part-time worker (see chart).

In fact, more than half (57 percent) of these adults work full- or part-time themselves. And the overwhelming majority of workers eligible for Medicaid — 81 percent — don’t have coverage through their employer because their employer either doesn’t offer it or it‘s unaffordable to them.

For those who aren’t working, tangible reasons, such as a chronic condition or serious mental illness, can preclude them from joining the workforce. One study found that among unemployed, uninsured adults likely to gain Medicaid coverage if their state adopted the Medicaid expansion, 29 percent weren’t working because they were caring for a family member, 20 percent were looking for work, 18 percent were in school, 17 percent were ill or disabled, and 10 percent were retired.

Contrary to what these proponents of work requirements believe, Medicaid can actually help individuals find and keep a job. States can offer supportive employment services to people with mental illness, 17.8 percent of whom are unemployed. They often want to work and can do so if they receive appropriate employment supports, such as job training.

Several states, including Iowa, Mississippi, and Wisconsin, have implemented supportive employment programs for people with mental illness. While each state’s approach differs, they’re all modeled off of evidence-based programs that have been shown to help participants find and maintain employment. These programs provide an array of services, such as skills assessment, assistance with job search and job applications, job development and placement, job training, and negotiation with prospective employers.

Imposing work requirements on low-income adults is inappropriate and can be counter-productive. Such requirements can cause people who aren’t working due to a chronic condition or mental illness to remain out of Medicaid and uninsured, which means that they miss out on mental health, substance abuse, or other treatment that might help them become more employable.