BEYOND THE NUMBERS

September not only marks the end of summer and back-to-school time for many children. It is also when the U.S. Department of Agriculture publishes annual data on the prevalence of food insecurity in the United States. The new data released last week show that, following a robust policy response that helped many families meet their food needs, overall rates of food insecurity remained steady in 2021. There was a small but not statistically significant decline in the share of households experiencing food insecurity (meaning that they did not have enough food to support an active, healthy life at some point during the year) compared to 2020 and 2019. However, this overall stability masks two important findings: first, while food insecurity among households with children remains high, it returned to pre-pandemic levels in 2021 after a significant relief effort. Second, persistent racial disparities in food insecurity among children continued. Both findings illuminate an important opportunity to address child hunger in the future by establishing a permanent summer EBT program.

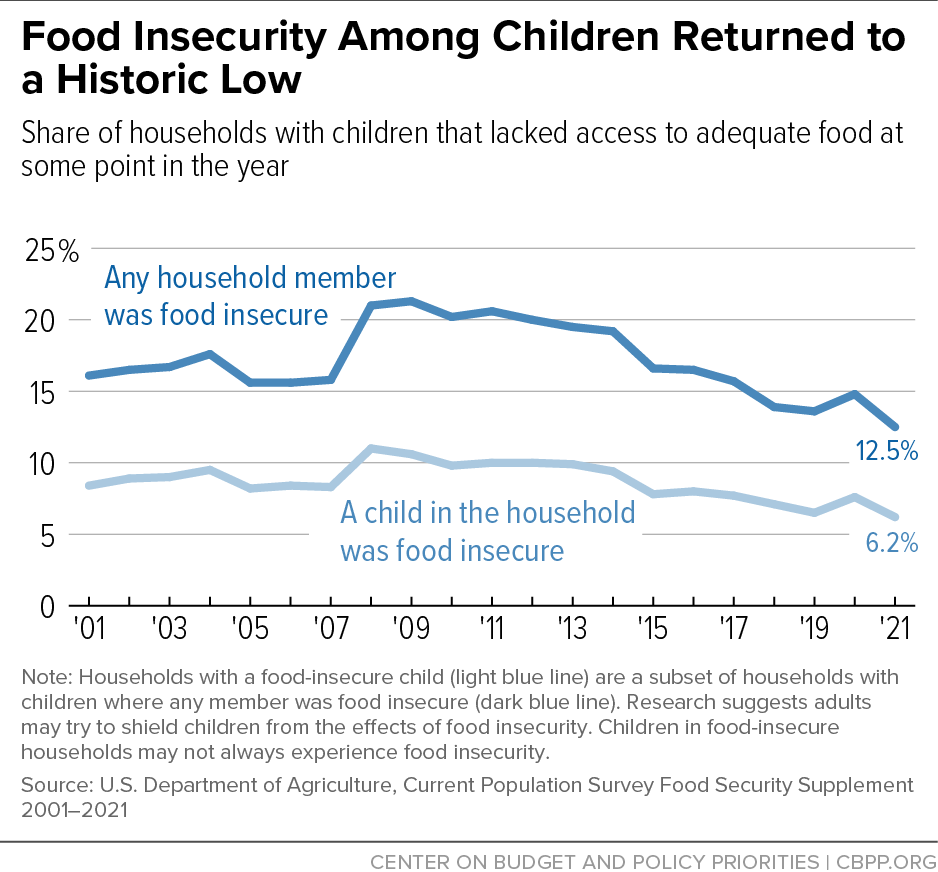

Households with children have long experienced higher rates of food insecurity than households without children, and this trend continued in 2021. However, the prevalence of food insecurity among households with children fell substantially, from 14.8 percent in 2020 to 12.5 percent in 2021. The share of households where children were food insecure reached a two-decade low in 2019 (6.5 percent of households with children) but increased significantly early in the pandemic, rising to 7.6 percent of households with children in 2020. However, this measure returned to the pre-pandemic low in 2021 (6.2 percent). (See first chart.)

It’s notable that the rate of food insecurity among households with children declined in 2021 despite unemployment rates remaining above pre-pandemic levels and the rising cost of food and other basic necessities. This may reflect the effectiveness of the policy response to the pandemic, including measures specifically targeted to families with children. These include the expanded Child Tax Credit and Pandemic EBT (P-EBT), which provides grocery benefits to replace free or reduced-price school meals for children in low-income families when schools are closed or operating under reduced hours due to COVID.

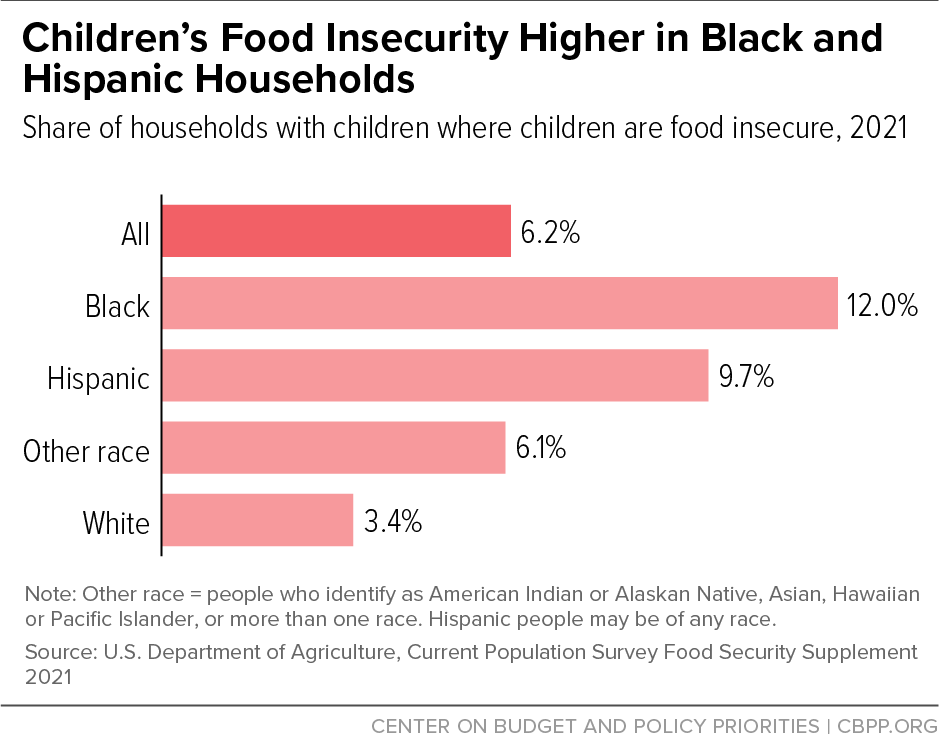

The new data also show that disturbing racial disparities in rates of food insecurity persist, including among households with children. Though the share of households with children who were food insecure declined in 2021 across most racial and ethnic groups, 12 percent of households with children headed by a Black adult and 9.7 percent of households with children headed by a Hispanic adult included a child who experienced food insecurity in 2021, compared to only 3.4 percent of households with children headed by a white, non-Hispanic adult. (See second chart.)

Despite improvements in 2021, the prevalence of food insecurity among children, and particularly among children in households of color, remains very high — and even temporary periods of hunger can have lasting impacts on children’s health and development. Further, many of the supports for low-income families during the pandemic, including the expanded Child Tax Credit and P-EBT, were temporary measures that have ended or will soon expire.

Looking ahead, these findings also underscore an opportunity to address a long-standing, critical gap in federal anti-hunger programs: many children in families with low incomes who receive free and reduced-price school meals during the school year struggle with hunger when school is out. Households with school-age children experience higher rates of food hardship during the summer, but existing summer meals programs typically reach just 1 child for every 7 children who rely on free or reduced-price school meals. This is in part because these summer meals programs, which require that children eat on-site in a group setting, aren’t available in every community and may be difficult for families with transportation, child care, or other barriers to reliably access.

But there is a clear path forward to closing this summer hunger gap: establishing a permanent, nationwide summer EBT program. Under this model, families with children who qualify for free or reduced-price school meals are provided grocery benefits on a debit-like EBT card during the summer. This avoids many of the barriers that may limit access to other summer meals programs, since families can redeem their benefits when they do their usual grocery shopping.

Summer EBT was first tested in limited demonstration projects starting in 2011 and found to be effective in reducing food insecurity and improving diet quality for low-income families with children. In response to the pandemic, Congress created the P-EBT program, modeled on the summer EBT demonstration projects, and later extended it to cover summer periods starting in 2021. As a result, children in nearly all states received grocery benefits for the summer of 2021 and in most states for the summer of 2022. Several analyses have shown that P-EBT substantially reduced food hardship among children and was a relatively low-cost approach that reached a significant proportion of eligible children.

However, P-EBT is a temporary measure that is tied to the federal COVID-19 public health emergency. Because the public health emergency has continued into the 2022-2023 school year, states will have the option to offer summer EBT next summer, at least for school-age children. But Congress will need to act to continue this successful program and avoid the seasonal spike in child hunger during the summer months in the future.

Legislation to create a permanent nationwide summer EBT program has been introduced each Congress for nearly a decade, often with bipartisan support, and there has been some recent progress in advancing a summer EBT program to become law. A permanent summer EBT program passed the House of Representatives in November 2021 as part of the reconciliation package, though it was not included in the enacted version of the bill. In July, the House Committee on Education and Labor took another important step by advancing the Healthy Meals, Healthy Kids Act out of committee, which included a $75 per month summer EBT benefit for eligible children. It also included a provision to establish statewide online school meal applications, which would help facilitate implementation of a permanent summer EBT program by simplifying program enrollment for states, schools, and families.

While the latest food insecurity data show encouraging trends for households with children, there is much more work to be done. Congress should build on this progress to prevent child hunger year-round and to address persistent racial disparities in the prevalence of food insecurity by enacting a permanent summer EBT program.