BEYOND THE NUMBERS

The incoming Congress should give the IRS the funds to restore its ability to adequately collect revenue, a basic government function. IRS underfunding since 2010 has led to two concerning, related trends, as ProPublica reports: a significant decline in audit rates, especially among large corporations and high-income filers, and delayed refunds and drawn-out audits for low-income workers claiming Earned Income Tax Credits (EITC).

As we’ve explained, the President and Congress have cut total IRS funding by 18 percent since 2010 in inflation-adjusted terms, and the IRS workforce has shrunk by about a fifth. The enforcement division has been hardest hit, losing roughly 14,000 employees — more than one-quarter of the enforcement staff — since 2010. As of 2017, the IRS had only 9,510 auditors. “The last time the IRS had fewer than 10,000 revenue agents was 1953, when the economy was a seventh of its current size,” noted ProPublica reporters Paul Kiel and Jesse Eisinger.

These cuts didn’t happen overnight. As Kiel and Eisinger explain:

Had the billions in budget reductions occurred all at once, with tens of thousands of auditors, collectors, and customer-service representatives streaming out of government buildings in a single day, the collapse of the IRS might have gotten more attention. But there have been no mass layoffs or dramatic announcements. Instead, it’s taken eight years to bring the agency that funds the government this low. Over time, the IRS has slowly transformed, one employee departure at a time.

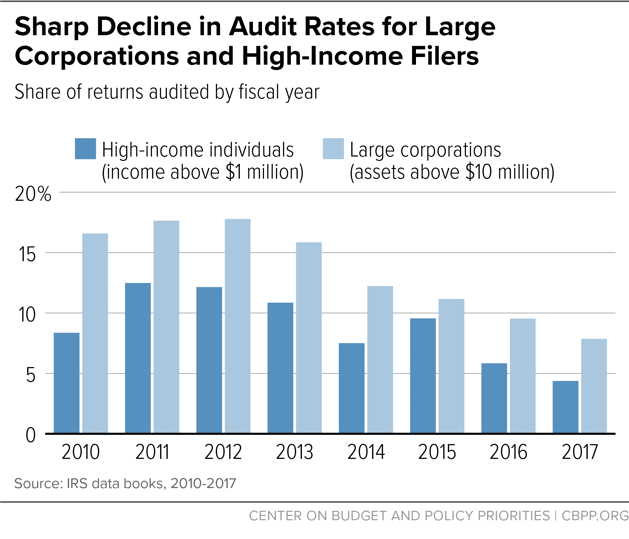

Largely due to these cuts, the audit rate has fallen from 16.6 percent to 7.9 percent for large corporations and from 8.4 percent to 4.4 percent for high-income individuals (see chart). (The IRS defines the term “audit” broadly to include not only face-to-face audits by field agents but also correspondence and phone calls between the agency and taxpayers after the latter file their returns.) EITC audits have also fallen over that span, but they have risen as a share of total IRS audits, according to ProPublica. They accounted for 36 percent of IRS audits in 2017 — more than 1 in 3 — reflecting policymakers’ calls for the IRS to increase its scrutiny of the credit. These enforcement priorities are upside-down: along with restoring adequate IRS funding, policymakers should refocus the agency’s enforcement attention on wealthy individuals and large corporations, where audits yield substantially higher returns.

Audits of higher-income individuals and businesses yield “much larger” average collections than those of lower-income taxpayers, according to a recent Congressional Budget Office report. In fact, the report concluded, increasing the IRS enforcement budget yields additional revenue at a rate of $5.20 per additional $1 devoted to enforcement.

The IRS’ current enforcement budget and strategy have had very different effects on taxpayers of different incomes. Not only has the audit rate dropped significantly for wealthy people, but the audits are less thorough. At the same time, the enforcement cuts have generated more challenges for low-income taxpayers, who often experience lengthy waits for refunds that are crucial for them to pay their bills because there aren’t enough IRS employees to timely resolve audit issues. Low-income filers also are much less equipped to weather an audit because they’re “much less likely to have competent representation to dispute the IRS’ conclusion,” ProPublica notes.

Due to staff shortages, the IRS regularly takes more than a year to release an EITC refund where an audit is involved, even for taxpayers who have representation, according to ProPublica. In addition, a recent analysis shows that EITC filers who have been audited are less likely to claim the EITC and file tax returns in the future even when they appear eligible for the credit and receive a notice from the IRS telling them that.

This audit imbalance is also important in the context of the 2017 tax law, which introduces several new opportunities to game the tax system. The law generates a strong incentive for wealthy individuals and profitable corporations to take advantage of new tax cuts for certain kinds of income by recharacterizing their income to fit the new tax breaks. For instance, individuals can seek to recharacterize their income as “pass-through” income — which the owners of businesses such as partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships claim on their individual tax returns — because the tax law provides a new 20 percent deduction for that income. The IRS will require significantly more resources and a different focus to prevent these gaming opportunities from draining more federal revenues.

Rather than continue squeezing the agency’s funding, the new Congress should give the IRS adequate resources to perform its core functions of collecting revenues and enforcing the nation’s tax laws. Moreover, it should encourage the IRS to put its primary audit focus where it belongs — on wealthy individuals and large corporations, where the returns from audits are the greatest — rather than overemphasizing audits of low-income filers.