BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Update, January 19: We’ve updated this post to clarify the description of the study.

A careful study reaches a conclusion that comports with common sense: better funding for schools leads to better long-term outcomes for students. With state legislative sessions beginning around the country this month, that’s a timely and important message, especially in the many states that haven’t restored funding cuts they enacted due to the Great Recession.

The study, by researchers from Northwestern University and the University of California, Berkeley, examined data on more than 15,000 children born between 1955 and 1985. During these children’s school years, some states raised funding for high-poverty schools due to court orders and other states didn’t, creating a fruitful environment for studying the impact of increased funding.

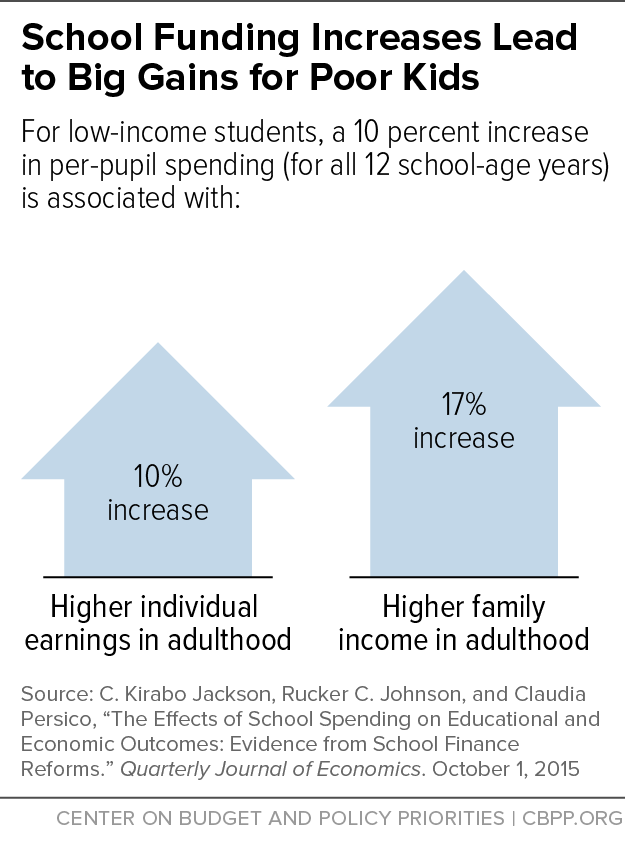

After controlling for such factors as enrollment growth and economic conditions, the researchers found that poor children whose schools were estimated to receive and maintain a 10 percent increase in per-pupil spending (adjusted for inflation) before they began their 12 years of public school had 10 percent higher earnings — and 17 percent higher family income — in adulthood (see chart). They also were likelier to complete high school and less likely as adults to be poor.

The researchers also found that a 10 percent increase in school spending is associated with 1.4 more school days per school year, a 4 percent increase in base teacher salaries, and a 6 percent reduction in student-teacher ratios.

This evidence highlights the importance of investing in schools, especially in states that have cut funding. Our recent report found that at least 31 states provided less funding per student in the 2014 school year (the most recent year for which we have these data) than in the 2008 school year, before the recession took hold. In at least 15 states, the cuts exceeded 15 percent.

In the current school year, at least 25 states are still providing less “general” or “formula” funding — the main form of state K-12 funding — per student than in 2008.

The new evidence of long-term gains from better K-12 funding suggests that restoring state funding cuts can benefit not just students but states’ economic prospects. At a time when the nation is trying to produce workers with the skills to master new technologies and adapt to the complexities of a global economy, underfunding basic education undermines a crucial building block for future prosperity.