BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Commission Urges Strengthening Evidence-Building Capacity, Yet House Considers Cutting Proven Low-Income Programs

A congressionally mandated commission has outlined ways that public agencies can help researchers access more government data and hence contribute to more effective public policy — just as Congress is considering deep cuts to economic security programs that, much evidence finds, are effective in helping struggling Americans. Congress should heed the large volume of research, which CBPP described in a major report, showing that economic security programs substantially reduce poverty and can help poor children succeed in the long term.

The House is expected to soon consider a 2018 budget resolution. The 2018 blueprint that the Budget Committee approved and that may come to the House floor calls for $2.9 trillion in cuts over the coming decade to programs serving low- and moderate-income people — and some of these cuts might end up paying for tax cuts, which would overwhelmingly benefit the wealthy and profitable corporations, that the blueprint envisions. Such an approach would be counterproductive: a large body of evidence shows that these economic security programs not only bolster family income and reduce poverty in the short term but can also help low-income children do better in school and improve their earning potential as adults.

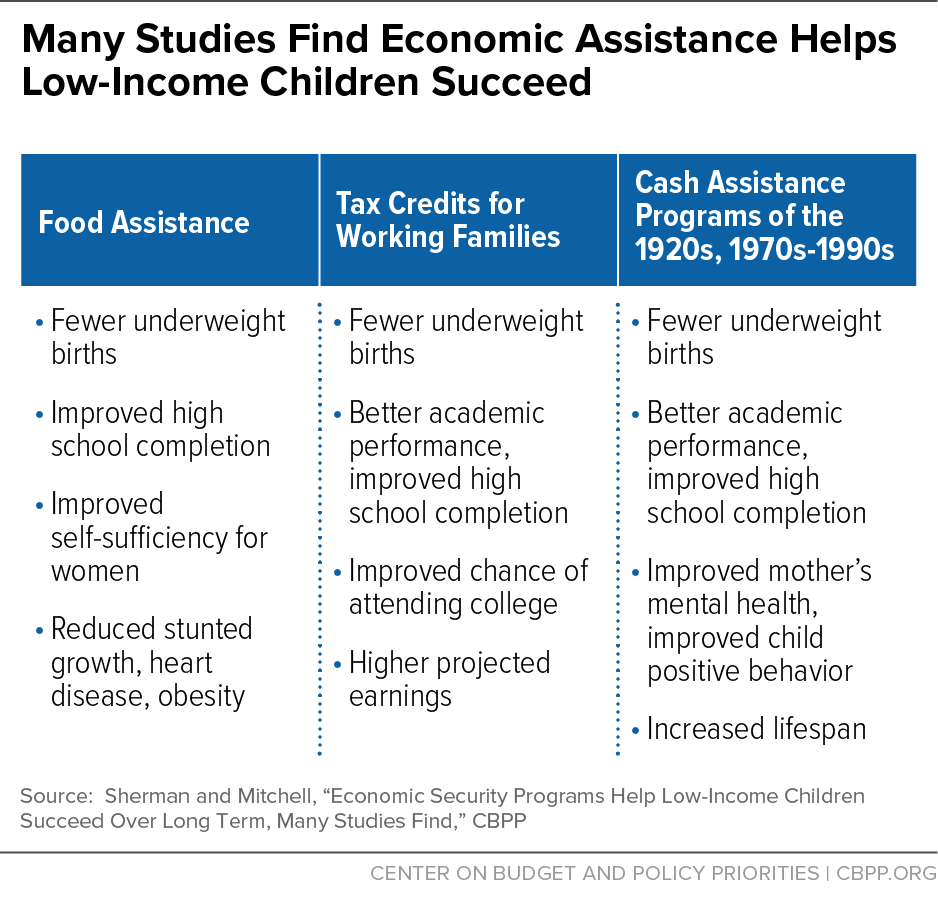

Programs such as food assistance, working-family tax credits, and housing subsidies can improve children’s health outcomes at birth, raise their middle-school reading and math scores, increase their high school completion and college entry rates, lift their lifetime incomes, and even extend their longevity, the evidence suggests. The findings come from studies of SNAP (formerly food stamps), the Earned Income Tax Credit, anti-poverty and welfare-to-work pilot programs in the 1990s, and various other programs. These are prudent investments: society benefits when low-income children succeed and can better contribute to their communities as adults.

Researchers are still exploring why adequate higher family income helps children over the long term. It may help by reducing severe poverty-related stress, a condition that scientists have linked to lasting consequences for children’s brain development and physical health. Another topic that needs further study is the stage of childhood at which income matters most. Such research could benefit from the commission’s recommendations for improved access to, and alignment of, federal data across public programs and for strengthening the government’s program evaluation function.

Policymakers can achieve substantially better results for the major decisions before them this fall if they base those decisions on evidence-driven policymaking instead of partisanship. And the evidence calls for protecting and strengthening income supports, not cutting them, as a long-term investment in children and in our shared economic future.