- Home

- State Budget And Tax

- To Support Education, Congress Should Pr...

To Support Education, Congress Should Provide Substantial Fiscal Relief to States and Localities

Testimony of Michael Leachman, Vice President for State Fiscal Policy, Before the House Committee on Education and Labor

Chairman Scott, Ranking Member Foxx, and distinguished members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify today. My name is Michael Leachman, Vice President for State Fiscal Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan research and policy institute in Washington, D.C.

My testimony will explain why it is crucially important for Congress to provide substantial additional fiscal aid to states and localities — soon — so they can properly fund our nation’s schools.

Pandemic Crippling State and Local Finances

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused state revenues to fall off the table, creating a fiscal crisis unlike anything states have faced since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Because of the virus, millions of businesses closed and an extraordinary number of people lost their jobs within a very short period of time. As a result, businesses collected much less in sales tax and withheld much less in income taxes from their workers’ paychecks. That created a stunning, sudden fiscal crisis for states, which rely on sales and income taxes for 70 percent of their revenue. Other state revenue sources also declined sharply; gas tax revenues plummeted, for example, because people were sheltering in place and not driving.

This happened all over the country. There’s nothing partisan about the virus.

These revenue losses are largely permanent. People aren’t going to get back the income they lost when they were laid off or furloughed, and states aren’t going to receive the tax revenue they lost as a result. A sizeable share of the businesses that were shuttered aren’t ever going to reopen, and the economy is going to take some time to fully recover. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects unemployment will still be over 8 percent at the end of next year. No one knows for sure how the economy will respond, but state revenues will very likely be depressed for quite a while.

Meanwhile, states face rising costs that are typical during any recession. Many workers who were laid off have turned to Medicaid and other forms of public assistance to get by, for example. Plus, states face highly unusual additional costs due to the pandemic, which I address below.

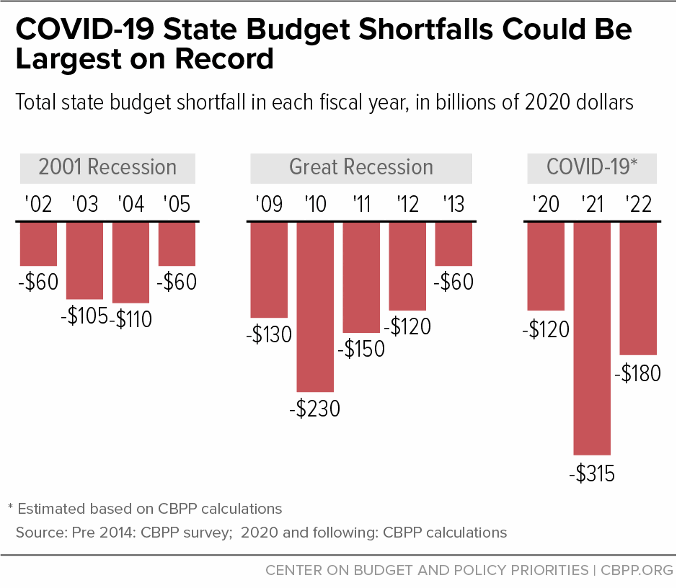

The sharp revenue losses, combined with even the normal increased costs of entering a recession, have created massive, and indeed unprecedented, state budget shortfalls. Based on history and economic projections from CBO and the Federal Reserve, we project these shortfalls will total $615 billion over the next three state fiscal years. (See Figure 1.)

The federal aid provided so far can close roughly $100 billion of those gaps, leaving states $515 billion short. Even if states use all of their “rainy day” funds (reserves designated for responding to unanticipated revenue declines or spending needs), which totaled $75 billion heading into the downturn, they would still fall $440 billion short.

Moreover, these estimates do not include states’ highly unusual added costs due to COVID-19. School districts, for example, face substantial unanticipated costs, including access to devices and connectivity for distance learning, food assistance for students from low-income families, and expanded learning time to offset the learning loss caused by school closures. Expanded learning time alone could cost districts $36 billion in the coming year, the Learning Policy Institute estimates.[1] Some of these costs can be covered using federal aid provided under the CARES Act, but not all.

Further, our shortfall estimates are for states only. While local revenues tend to be more stable than state revenues because localities rely primarily on property taxes, reasonable estimates conclude that localities also face large shortfalls, as do tribal governments and U.S. territories, including Puerto Rico.

States and Localities Already Starting to Cut School Funding

The state and local fiscal crisis could have a severe impact on public education. Across the country, states provide 47 percent of K-12 funding, while localities provide 45 percent. And K-12 funding constitutes about a quarter of state budgets, making it a prime target for lawmakers looking to cut at a time of large shortfalls.

In the last two months, states and localities already have furloughed or laid off more than 1.5 million workers, twice the number they laid off in the aftermath of the Great Recession. About half of these workers — more than 750,000 people — were employed by school districts.

Most of these people were furloughed rather than fully laid off, so many of them may get their jobs back when schools return to session. But many won’t — and many other school workers who haven’t yet been furloughed, including many teachers, will lose their jobs permanently in the coming weeks, unless the federal government provides substantially more fiscal aid.

Several states have already announced large education cuts that will harm children and families. Ohio Governor Mike DeWine has announced plans to cut $300 million in K-12 funding and $100 million in college and university funding for the current year. Meanwhile, Georgia’s top budget officials told the state’s schools to plan for large cuts for the fiscal year starting July 1, which will almost certainly force districts to lay off teachers and other school workers. More cuts are likely at the local level given localities’ budget challenges.

Lessons From the Great Recession

Whenever our kids return to school, a severely diminished learning experience awaits them unless the federal government learns an important lesson from the past and acts soon to boost state aid significantly.

The last time states faced a budget crisis, in the wake of the Great Recession of a decade ago, emergency federal aid closed only about one-quarter of state budget shortfalls. Because the aid provided was too little, states cut funding to K-12 schools in order to help meet their balanced-budget requirements. By 2011, 17 states had cut per-student funding by more than 10 percent. Local school districts responded to the loss of state aid by cutting teachers, librarians, and other staff; scaling back counseling and other services; and even shortening the school year. Even by 2014 — five years after the recession ended — state support for K-12 schools in most states remained below pre-recession levels.

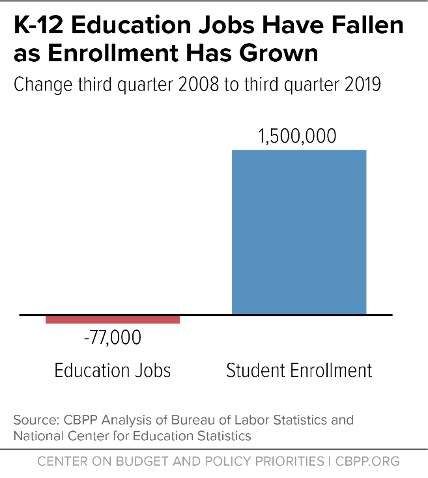

School districts have never recovered from the layoffs they imposed back then. When COVID-19 hit, K-12 schools employed 77,000 fewer teachers and other workers than they did when the Great Recession started to force layoffs, even though they were teaching 1.5 million more children (see Figure 2), and overall funding in many states was still below pre-Great Recession levels.

School districts have not recovered from Great Recession-era cuts in other ways as well. State capital funding for schools — to build new schools, renovate and expand facilities, and install more modern technologies, among other things — was 15 percent lower in 2018 than in 2008 as a share of the economy. That’s equivalent to a $12 billion cut.

Education Cuts Hurt Kids, Especially Low-Income Children and Children of Color

These funding cuts and layoffs hurt our kids, and hence our future. Money matters in education. Adequate school funding helps raise high school completion rates, close achievement gaps, and make the future workforce more productive by boosting student outcomes. School funding cuts during the Great Recession, for example, drove down test scores and college attendance rates.[2] The impact was particularly damaging for low-income students.

Indeed, while classrooms across America are at risk, the danger is greatest for low-income kids and children of color, for whom an excellent K-12 education is vital in overcoming historical barriers to opportunity. State funding typically reduces disparities between wealthy and poor school districts, so cuts in that funding magnify those disparities. That’s what happened with the Great Recession: state funding fell as a share of total school funding, increasing schools’ reliance on local funding, which comes primarily from property taxes. These taxes are heavily based on property values, which — due largely to historical racism and ongoing forms of discrimination — are much higher in wealthier areas where more white people live, making it easier for these residents to raise revenue for schools.

Another reason why state funding cuts tend to fall particularly hard on low-income children and children of color is that state and local funding structures tend to underfund schools even in good times. Districts with larger shares of students of color receive some $1,800 less per student than districts with smaller shares, a 2018 Education Trust report found. Those disparities add up: in a modest 5,000-student district, the cumulative gap is $9 million, while for a moderate-sized 25,000-student district it’s $45 million.[3]

Funding disparities are apparent across class lines, too, though less starkly than across racial lines. Districts serving large shares of poor students receive $1,000 less per pupil than the lowest-poverty districts, on average. And only about a third of states provide more funding to high-poverty school districts than to low-poverty ones, even though poor children need more support.[4]

Federal Aid for States and Localities Would Boost Economy at a Crucial Time

Aid for states and localities would protect not only protect kids’ education, but also jobs and the economy now, as economists across the political spectrum have pointed out. For example:

- Economist Glenn Hubbard, former Chair of President George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers, recently said, “This is a critical time to provide additional assistance to state and local governments. . . . Just as in the CARES Act, [where] we wanted to avoid excessive layoffs in the private sector, so too do we want to in the public sector. The same economic logic ports over.”[5]

- As Christina Romer, former Chair of President Barack Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, described in detail just last year, a careful study of the 2009 Recovery Act’s state fiscal relief found that states that received more aid produced more jobs as a result, at a lower cost per job than other forms of stimulus.[6]

- Mark Zandi, Chief Economist at Moody’s Analytics, testified that every dollar that the Recovery Act provided in general aid to state governments produced $1.41 in economic activity, a strong “bang for the buck.”[7] Zandi recently said, “If states don’t get additional support and my economic outlook holds, I would expect that state and local governments will shed another close to 3 million jobs over the next 12 to 18 months.”[8]

- CBO estimated that the fiscal relief provisions in the 2009 Recovery Act delivered a “bang for the buck” of up to $1.80.[9] As former CBO director Doug Elmendorf recently said, “[L]aying off governmental workers means more people who can’t go out and buy things from small businesses. . . . And so we want to keep people at work in state and local governments . . . so that as the health conditions improve we can have people spending money to create a strong recovery.”[10]

- The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco’s review of the economic literature suggests the Recovery Act’s boost to local government spending produced about a $1.50 “bang for the buck.” In the current crisis, the Bank emphasizes, federal transfers to state and local governments will likely be spent quickly, maximizing the economic benefit.[11]

Pandemic, Not State Fiscal Management, Is Responsible for the Crisis

Some argue that states’ financial management is responsible for the fiscal crisis, but the facts don’t support that claim.

States did a reasonable job of saving for a recession before the pandemic hit: states held much larger reserves when this crisis struck than when the last recession started. Heading into the current crisis, state rainy day funds equaled about 7.6 percent of state budgets, versus about 5 percent in 2006, the high point before the Great Recession. And total state reserves, which include general-fund ending balances, now equal about 13 percent of state budgets, also well above 2006. Similarly, in 38 states the trust funds that support state unemployment insurance programs were better prepared for the current crisis than for the Great Recession, and most state trust funds met the U.S. Labor Department standard for recession preparation. The problem is that state revenues have fallen so severely that the resulting shortfalls are swamping states’ reserves.

Nor have states been overspending. As a share of the economy, spending from state general funds (which support current operations, like schools, health care, the justice system, and public health) is well below its levels heading into the last downturn. In some key areas, in fact, states have been too frugal. As noted above, states still employ fewer teachers and other school workers than a decade ago, even though many more students are enrolled. Similarly, state funding for higher education per pupil is down 13 percent on average from roughly a decade ago, after adjusting for inflation, pushing up tuition and making college less accessible. And spending on infrastructure stands at historic lows as a share of the economy.

The claim that states would spend additional federal aid primarily on pensions also is mistaken. Emergency federal aid would go into state general funds, which are collapsing for the reasons noted above. States pay retirees’ pension benefits out of separate trust funds. While states (and localities) use general funds to make regular payments toward future pension obligations, these payments amount to only about 4.7 percent of state and local general fund spending, on average. And every state has adopted pension reforms over the last decade, leaving benefits for new employees in many states significantly weaker on average.

What’s Needed Now

Congress has provided some state and local aid so far, but much too little to avoid teacher layoffs and other harmful spending cuts. While states alone face budget shortfalls of about $615 billion (and localities face significant shortfalls), Congress has provided only roughly $100 billion in fiscal aid that states will be able use to address their revenue shortfalls. This includes $30 billion for education, of which only $13 billion is dedicated to K-12 schools.

That’s much less than the roughly $160 billion Congress provided under the Recovery Act, which included $60 billion primarily for education. And the Recovery Act’s fiscal aid proved much too small and ended too soon. Congress simply must do better this time.

The House-passed Heroes Act provides significant state and local fiscal aid through multiple mechanisms. These include $500 billion in direct grants for states, an increase in the federal Medicaid matching rate, about $60 billion to support schools, additional aid for higher education, and aid for localities. In total, this amount of fiscal aid is appropriate to the extraordinary crisis states and localities face.

In designing an aid package, it’s crucial that Congress dedicate some of the funds specifically for schools to protect school funding. The amount of aid provided directly to schools under the Heroes Act would not, on its own, allow states to avoid cuts that would result in teacher layoffs and other harm for schools. States and localities could use other forms of aid in the Act to protect schools, but it’s not certain that they will, given the many challenges they face. As such, we would support a significant increase in the amount of direct aid for schools in the final package.

School aid should be distributed in a way that prioritizes low-income districts, as the Heroes Act would accomplish by using the Title I funding formula. It also should include both a “maintenance of equity” requirement that states avoid funding cuts disproportionately affecting low-income districts and a “maintenance of effort” requirement that states continue support for schools at pre-crisis levels as a share of the state budget.

Besides aid dedicated to schools, states will need other forms of fiscal relief to avoid harmful layoffs, other cuts, and tax increases. Raising the federal Medicaid matching rate, as under the Heroes Act, is a particularly effective form of broad state fiscal relief because it can be delivered quickly, without complex guidance and unnecessary restrictions. Raising the matching rate is also especially compelling during the current downturn because it can include a provision that bars states from cutting Medicaid eligibility at a time when access to health care is especially important. By providing direct savings to states, raising the matching rate frees up funds they can reallocate to protect schools and other fundamental public services.

Finally, an adequate fiscal aid package will likely need to include direct, flexible grants to states and localities, like those in the Heroes Act. States and localities should have the flexibility to use these grants to make up for revenues lost due to the pandemic.

Ideally, some or all of this aid would be distributed based on economic indicators so it would adjust depending on the state of the economy, ending sooner if the economy recovers more quickly than CBO and other forecasters predict but remaining in place as long as needed if the recovery is unexpectedly slow.

The pandemic has caused a severe state fiscal crisis. Without significant federal aid, soon, states and localities will lay off teachers and other workers and take additional steps that worsen the recession, delay the recovery, and weaken students’ education. We can’t let that happen.

End Notes

[1] Michael Griffith, “What Will It Take to Stabilize Schools in the Time of COVID-19?” Learning Policy Institute, May 7, 2020, https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/blog/what-will-it-take-stabilize-schools-time-covid-19.

[2] C. Kirabo Jackson, Cora Wigger, and Heyu Xiong, “Do School Spending Cuts Matter? Evidence from the Great Recesssion,” NBER Working Paper 24203, revised August 2019, https://www.nber.org/papers/w24203.

[3] Ivy Morgan and Ary Amerikaner, “Funding Gaps: An Analysis of School Funding Equity Across the U.S. and Within Each State, 2018,” The Education Trust, February 2018, https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/FundingGapReport_2018_FINAL.pdf.

[4] Bruce D. Baker, Danielle Farrie, and David Sciarra, “Is School Funding Fair? A National Report Card,” Seventh Edition, Education Law Center and Rutgers Graduate School of Education, February 2018, https://drive.google.com/file/d/1BTAjZuqOs8pEGWW6oUBotb6omVw1hUJI/view.

[5] Economic Policy Institute press call, June 1, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kk_4IIVPBXA&t=651s.

[6] Christina Romer, “The Next Recession,” Economic Policy Institute, May 15, 2020, https://www.epi.org/publication/the-next-recession-keynote-address-by-christina-romer/.

[7] Testimony of Mark Zandi, Chief Economist, Moody’s Analytics, Before the Senate Finance Committee, April 14, 2010, https://www.economy.com/mark-zandi/documents/Senate-Finance-Committee-Unemployment%20Insurance-041410.pdf.

[8] Economic Policy Institute press call, June 1, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kk_4IIVPBXA&t=596s.

[9] Congressional Budget Office, “Estimated Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act on Employment and Economic Output from January 2012 Through March 2012,” May 2012, http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/05-25-Impact_of_ARRA.pdf.

[10] Testimony before the House Budget Committee, June 3, 2020.

[11] Daniel J. Wilson, “The COVID-19 Fiscal Multiplier: Lessons from the Great Recession,” FRBSF Economic Letter, May 26, 2020, https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2020/may/covid-19-fiscal-multiplier-lessons-from-great-recession/.

More from the Authors