As a result of the tax cut-unemployment insurance legislation that President Obama signed into law last week, economic forecasters have substantially upgraded their outlook for 2011 (see the box on page 2). An analysis of the compromise by Mark Zandi, the chief economist for Moody’s Analytics, indicates that this greater optimism stems largely from the longer extension of federal emergency unemployment insurance (UI) programs than forecasters had expected, the extension of various improvements enacted in 2009 in several tax credits for low- and modest-income families, and a reduction in the payroll tax. By contrast, the extensions of the upper-income Bush-era tax cuts and a substantially weakened estate tax will provide little or no boost to the economy in the short run; moreover, those extensions increase the risk that such measures will ultimately be made permanent and thereby deal a setback to efforts to restore long-run fiscal balance.

- In a December 8 analysis of the compromise legislation,[1] Zandi finds that, compared with Moody’s pre-compromise economic forecast, the deal would add 1.2 percentage points to economic growth and 1.6 million jobs to payroll employment in 2011, while lowering the unemployment rate by 1.2 percentage points. (Moody’s pre-compromise forecast already assumed enactment of several measures that were part of the compromise, most notably extension of the “middle-class” tax cuts. Please see the box on page 4 for a more detailed explanation of the measures in the compromise.)

- Zandi also finds that what he terms the “Democratic Proposals” in the package — the 13-month extension of UI benefits (Moody’s pre-compromise forecast assumed only a three-month extension), the extension of various refundable tax credit improvements enacted in the 2009 Recovery Act, the reduction in the payroll tax, and the “expensing” provision for businesses — account for 1.1 percentage points of the 1.2 percent boost to real economic growth in 2011, 1.4 million of the 1.6 million-job increase in payroll employment, and 1.1 percentage points of the 1.2 percentage-point reduction in the unemployment rate.

- In other words, Zandi estimates that about 90 percent of the expected improvement in economic and job growth and the reduction in the unemployment rate will be due to the UI and tax provisions the Administration promoted, while the high-end tax provisions will have only very small economic impacts.

| Prior to announcement of the compromise, most economic forecasters already assumed that the “middle-class” Bush-era tax cuts and certain other tax provisions would be extended into 2011. The precise assumptions varied from forecaster to forecaster, but as the following quotes show, the broad scope of the compromise — which went beyond what forecasters had anticipated — led them to upgrade their forecasts for 2011. Moody’s Analytics: “compromise boosts stimulus”a The deal’s surprisingly broad scope meaningfully changes the near-term economic outlook. Real GDP growth in 2011 will be nearly 4%, approximately 1 percentage point greater than previously anticipated. Job growth will be more than twice as strong, with payrolls growing by 2.6 million. Unemployment will be more than a percentage point lower; instead of hovering near 10% through the year, it will end 2011 well below 9%. Goldman Sachs: “fiscal package should boost growth in 2011”b The bipartisan agreement should reduce by about 0.9 percentage points the drag that we expected federal fiscal policy to exert on annualized real GDP growth in 2011. Macroeconomic Advisers: “significant positive, if temporary, macroeconomic effects”c [These] alternative tax and unemployment-benefit policies would, relative to our baseline, raise GDP growth by 0.6 percentage points over the four quarters of 2011 [from 3.7% in our base forecast to 4.3%]… The boost to growth would be successful in speeding the decline in the unemployment rate. By the end of 2011, the unemployment rate is 0.4 percentage point lower, but by the end of 2013, the unemployment rate has converged (from below) to the same level as in the base forecast. As discussed in the body of this paper and illustrated in the Goldman Sachs quote, the primary benefit of the stimulus from the compromise package will be to bring the unemployment rate down faster than it would otherwise decline and to increase cumulative output, income, and employment over the next few years. These effects will wane, as they should, as the recovery gathers underlying strength and sustainability. _______________________ a Mark Zandi, “U.S. Macro Outlook: Compromise Boosts Stimulus,” Moody’s Analytics, December 8, 2010. b Alec Phillips, “The Fiscal Package: A Boost to Growth in 2011,” Goldman Sachs U.S. Economic Analyst, December 10, 2010. c Macroeconomic Advisers, “The Tax Compromise: It’s Complicated,” Macroeconomic Advisers’ Macro Musing, Volume 13, Number 26, December 8, 2010. |

- In a similar vein, in a separate analysis that the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities requested and Zandi completed before the compromise was announced, he found that a package looking much like the measures that the Administration sought in the negotiations would generate substantially more economic activity — including creating 1.2 million more jobs next year — than would a permanent extension of the Bush-era upper-income tax cuts, while adding far less to budget deficits over the 2010-2020 period.[2]

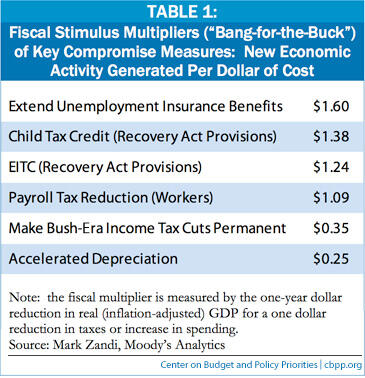

Many analysts, including the Congressional Budget Office[3] as well as Zandi, have found that in a weak economy, UI and refundable tax credits — and other measures that put money into the hands of hard-pressed individuals and families who will spend it — have a significantly larger impact on economic activity and job creation than tax cuts primarily benefiting high-income individuals, who are likely to save a large amount of any increase in income they receive. In the Moody’s Analytics model, extending unemployment insurance benefits generates $1.60 of additional GDP for each dollar of budgetary cost, while a permanent extension of all of the Bush-era income tax cuts generates only 35 cents in economic activity per dollar of cost. The “bang-for-the-buck” of just the upper-income tax cuts would be even smaller. Table 1 shows Zandi’s estimates for these and other prominent measures in the compromise legislation.

Fiscal multipliers measure how much additional economic activity is generated per dollar of budgetary cost. The economic impact of a

package of measures thus depends on the size of each of the components of the package and their respective fiscal multipliers. The bipartisan measures that most forecasters were already assuming would be enacted were proposals that have modest bang-for-the-buck but involve a lot of bucks. Allowing all of them to lapse at the end of this year thus would have dealt a blow to a fragile economic recovery, and this concern motivated the effort to come up with a compromise to prevent that from occurring.

The political compromise involved the White House swallowing a two-year extension of the upper-income tax cuts and a weakening of the estate tax in return for a full-year extension of both federal unemployment insurance and various targeted low- and middle-income tax cuts enacted in 2009 and a business “expensing” tax incentive the President had proposed in September. Republican negotiators would not accept an extension of the Making Work Pay tax credit created by the 2009 Recovery Act, but they agreed to accept the payroll tax reduction as an alternative and the President’s proposed business tax cut. Missing from the discussion were policies to increase government spending for infrastructure or other purposes or to provide further fiscal assistance to state and local governments — measures that have more bang-for-the-buck than most tax cuts do. [4]

| Zandi separates the measures in the compromise legislation into three categories: Democratic measures, Republican measures, and bipartisan measures. This box describes the major provisions in each category.a “Democratic Measures” Federal unemployment insurance (UI). The provision of additional weeks of federally funded UI benefits, which had expired on November 30th, was restored through the end of 2011. Obama-era tax cuts. The 2009 Recovery Act included temporary expansions in three tax credits for low- and middle-income households. It expanded the Child Tax Credit by lowering the amount of earnings that working-poor families must have to qualify for the credit. (Families with earnings below this threshold amount are denied the credit altogether, and those with earnings in a range that extends some thousands of dollars above the threshold amount receive only a partial credit.) The Recovery Act also improved the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) by modestly increasing the size of the tax credit for families with three or more children and by adjusting the credit so low-income workers have their EITC reduced less (if at all) if they marry. Finally, the Recovery Act created the American Opportunity Tax Credit by expanding (and renaming) the former Hope Credit, which provided a tax subsidy for college tuition costs. The maximum amount of this credit was increased, and the credit was made partially available for the first time to students from families with earnings too low to owe income tax. The compromise legislation extends these changes for two more years. Payroll tax reduction . All workers’ payroll taxes are reduced by 2 percentage points for 2011 (from 6.2 percent to 4.2 percent of the first $106,800 in earnings). In return, the Making Work Pay (MWP) tax credit created in the 2009 Recovery Act will expire on schedule at the end of 2010. The MWP credit was better targeted to low- and middle-income working families because it was a fixed amount and refundable, but the aggregate size of the payroll tax reduction is larger. Business investment incentives . The compromise accelerates the pace at which businesses can deduct depreciation on their investments. This will increase businesses’ cash flow in the next few years and cause a reduction in federal tax revenue during this period. Much of the budgetary cost will be recouped in subsequent years, when businesses will take smaller depreciation deductions. “Republican Measures” High-income tax cuts. The expiring Bush-era tax cuts for taxpayers with annual incomes above $250,000 for couples ($200,000 for individuals) are extended for two years. These tax cuts consist of reductions in the top two marginal tax rates and in the tax rates on capital gains and dividends, as well as continuation of the full value of exemptions and deductions for high-income taxpayers. (Pre-2001 tax law reduced the value of exemptions and deductions for this group). Estate tax . The compromise sets new rules for the estate tax for the next two years. An extension of the estate tax at rules no less lenient than those in effect in 2009 (a tax rate of 45 percent on the taxable portion of an estate, with the first $3.5 million of the value of an individual’s estate — effectively, the first $7 million of a couple’s estate — being exempted) was a foregone conclusion before the negotiations started, but the negotiations resulted in a further weakening of the tax. For the next two years, the first $5 million of an estate for an individual — $10 million for a couple — will be exempt, and the taxable portion of an estate will face a 35 percent tax rate. “Bipartisan Measures” The measures in the compromise that Zandi labels “bipartisan” were ones that most forecasters had already assumed would be extended. These include: a two-year extension of the Bush-era middle-income tax cuts for taxpayers with incomes up to $250,000 for couples ($200,000 for individuals); a one-year patch to the Alternative Minimum Tax; a one-year extension of certain expiring tax provisions; and an extension of the estate tax under the 2009 rules, as described above. __________________________ a For a cost breakdown of the compromise, see Gillian Brunet and Chuck Marr, “Unpacking the Tax Cut-Unemployment Compromise,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 10, 2010. |

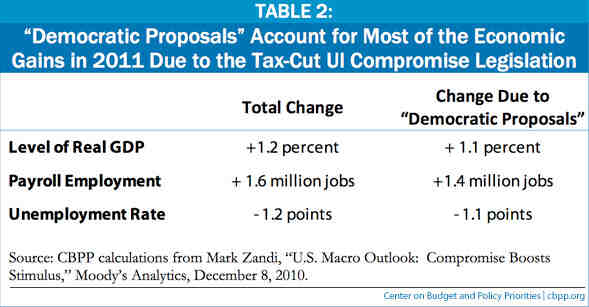

The inclusion of a 13-month extension of federal unemployment benefits and a two-year extension of several tax cuts targeted primarily to low- and modest-income households, as well as the new payroll tax reduction, is central to the added economic boost that analysts now expect to occur, which is leading them to raise their forecasts for economic growth and job creation in 2011. This can be seen clearly in Zandi’s analysis of the compromise legislation, by comparing his estimate of what the economy would look like if only the “Democratic” measures in the package had been incorporated into his pre-compromise forecast with what the economy will look like with all of the compromise measures included. [5] The results are striking, as Table 2 shows.

Zandi’s estimates show that the compromise will add 1.2 percentage points to real GDP growth in 2011, compared with Moody’s pre-compromise forecast. Of this boost, 1.1 percentage points are attributable to the “Democratic” measures in the package. Similarly, Zandi forecasts that payroll employment will be 1.6 million jobs higher under the compromise, with 1.4 million of these jobs attributable to the “Democratic” measures. Finally, the unemployment rate will be 8.7 percent in 2011, some 1.2 percentage points lower than in Moody’s pre-compromise forecast, with 1.1 of the 1.2 percentage point reduction being due to the “Democratic” measures.

The short-term stimulus in the compromise is front-loaded, with the federal unemployment insurance benefits and the payroll tax reduction terminating at the end of 2011. Commentators have noted that this means that the economic growth rate will be higher in 2011 than was anticipated before the compromise, but lower than had been anticipated in 2012.[6] The lower growth rate in 2012 will take place, however, from a higher level of GDP in 2011, so the resulting level of GDP in 2012 will be higher than had been anticipated before the compromise. The same outcomes are expected for 2013, after all of the compromise measures have expired: the level of GDP will be higher than it would have been without the compromise, while the rate of economic growth will be lower.

This pattern — higher levels of economic activity, higher payroll employment, and lower unemployment rates after 2011, but also lower economic growth rates and smaller increases in payroll employment and reductions in the unemployment rate — is an intended feature of the package, not a “bug.” Deficit-financed economic stimulus is a temporary policy to reduce the amount of economic slack in a weak economy and to restore sustainable high-employment growth more quickly. It is not meant to be kept in place indefinitely.

There is tremendous waste in an economy that operates with substantial excess unemployment and idle productive capacity. The goods and services not produced while the economy is in a protracted slump are lost forever, as is the income that workers do not earn when they are unemployed and that companies do not receive when their stores are empty and their factories and machines are idle. Lost income also means lost government revenue and larger budget deficits.

Until a strong, self-sustaining recovery is underway, well-targeted government expenditures and tax cuts can reduce this waste by generating more economic activity than there would be without such stimulus and by putting people back to work faster.

Of course, such stimulus also increases the budget deficit. It is misguided to try to offset this budgetary impact in the short term, since contemporaneous increases in taxes or reductions in expenditures would undermine the job-creating impact of the stimulus measures. But if possible, it would make sense to offset the budgetary impact with well-designed deficit-reduction measures that take effect down the road, when the economy is stronger.[7] Regardless of whether policymakers offset the cost, stimulus measures should be temporary so that they do not contribute to long-term structural deficits.

The real 2012 problem is the danger that the upper-income tax cuts and weakening of the estate tax will be extended again and subsequently made permanent. Unlike supporters of federal unemployment insurance benefits, who acknowledge that this program should end once the economy is back closer to full employment,[8] supporters of the high-end tax cuts and shrunken estate tax can be expected to push to make these provisions permanent — and to fight hard to keep them from expiring on schedule at the end of 2012.

Economic and Budgetary Trade-Offs in the Short Term and Longer Term

Zandi’s analysis of the compromise legislation focuses on the short-term impact of the package. However, the earlier Zandi analysis requested by CBPP highlights the trade-offs between various policy options over both the short term and the longer term.

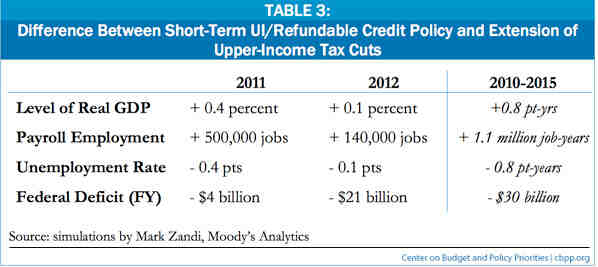

For the short term, Zandi compared the impact on the economy of two different policy packages: a) extending the upper-income tax cuts for two years but not continuing federal UI beyond its expiration on November 30, 2010; and b) extending federal UI for one year and the Obama tax credit improvements enacted in 2009 (the child tax credit expansion, EITC improvements, and higher education credit) for two years, while allowing the upper-income tax cuts to expire on December 30, 2010.

These two competing policy packages would each cost about $100 billion. But Zandi found that, relative to Moody’s pre-compromise economic baseline, [9] they would have very different economic effects. As shown in Table 3:

- The UI/refundable credit policy would raise payroll employment to a much greater degree than extending the high-income tax cuts would. The difference amounts to 500,000 more jobs in 2011, 140,000 more jobs in 2012, and 1.1 million more job-years over 2010-2015. (An increase of one job-year is an increase in payroll employment of one job, maintained for one year.)[10]

- The UI/refundable credit policy also would raise real GDP to a much greater degree than extending the high-income tax cuts would. The difference between these two sets of policies amounts to 0.4 percent of GDP in 2011 and diminishing amounts thereafter. Cumulatively, economic slack would be reduced by an additional 0.8 percentage-point-years of GDP over the 2010-2015 period under the UI/refundable tax credit policy. [11]

- The UI/refundable credit policy would also lower the unemployment rate to a larger degree than extending the high-income tax cuts would, with the difference amounting to 0.4 percentage points in 2011 and diminishing amounts thereafter.[12]

- Finally, the UI/refundable credit policy would add $30 billion less to the budget deficits in fiscal years 2010-2015 than extending the high-income tax cuts would, taking into account the effect of stronger economic growth on the deficit. [13]

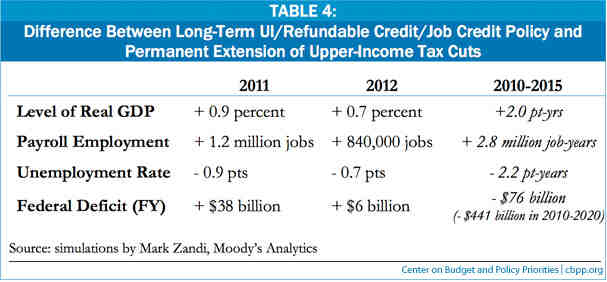

The longer-term analysis of the trade-off between upper-income tax cuts and UI/targeted tax cuts that Zandi conducted at our request also looked at the following two scenarios:

- a permanent extension of the high-income tax cuts, but no federal unemployment benefits beyond November 30, 2010, and

- a full-year extension of federal UI benefits, a permanent extension of the Recovery Act tax credit provisions for low- and modest-income households, and a one-year extension of the Making Work Pay tax credit, along with a new, two-year tax credit for firms that hire new workers — but no extension of the high-income tax cuts.

(This comparison did not include the provision of the new law that weakens the estate tax. If a permanent extension of the weakened estate tax had been included in the first option above, along with the permanent extension of the upper-income tax cuts, the longer-term deficit would have been made significantly worse, but there would have been no significant difference in the impact on economic performance in the 2010-2015 period.)

While the UI/tax cut scenario examined here is not identical to the “Democratic” measures in the compromise, it is similar to those measures. To be sure, in this scenario, the Obama-era tax cuts that were extended for two years in the compromise legislation would be extended permanently. But the Making Work Pay tax-credit provision and the tax credit for firms hiring new workers included in this Zandi scenario are roughly comparable to the payroll tax reduction and business tax cuts included in the compromise legislation. Moreover, this scenario would have a ten-year budgetary cost in the same range as the “Democratic” proposals in the compromise legislation. (Not surprisingly, this scenario is significantly less expensive than the ten-year budget cost of permanently extending the upper-income tax cuts.)

Table 4 shows the effect of these alternative scenarios, relative to Moody’s pre-compromise economic forecast. Zandi finds that the “Democratic” measures would produce a significant boost to the economy in 2011 and 2012, compared with the “Republican” measures. His analysis also shows the large increase in budget deficits and debt associated with the upper-income tax cuts. Compared with making the upper-income tax cuts permanent, a set of proposals similar to the “Democratic” measures in the compromise legislation would:

- add $76 billion less to budget deficits over the 2010-2015 period and $441 billion less from 2010-20, because the budgetary cost of the package of “Democratic” measures would be only half as large as the cost of making the high-income tax cuts permanent and because of the additional revenue generated by the stronger economic growth these measures would generate in the short term; [14]

- raise real GDP by 0.9 percent more in 2011, 0.7 percent more in 2012, and diminishing amounts thereafter. [15]

- raise payroll employment by 1.2 million more jobs in 2011 and 840,000 more jobs in 2012, ultimately adding 2.8 million more job-years to cumulative 2010-2015 payroll employment; and

- lower the unemployment rate by 0.9 percentage points more in 2011, 0.7 percentage points more in 2012, and diminishing amounts thereafter, ultimately resulting in 2.2 percentage point-years less of excess unemployment in the 2010-2015 period. [16]

Analysis of the impact of the compromise legislation on the economy and the budget, as well as analysis of the impact of alternative policy scenarios, illustrate that unemployment insurance benefits and refundable tax credits are much more powerful than upper-income tax cuts in stimulating economic activity and job creation in a weak economy. The inclusion of high-income tax cuts and a weakened estate tax may have been politically necessary to produce a deal that includes measures that should give the recovery a needed boost. But it is critically important that policymakers allow these tax cuts to expire on schedule at the end of 2012. These tax measures will provide little meaningful help in digging the economy out of the deep hole left by the 2007-2009 Great Recession, and if extended again, will add significantly to the burden of addressing the nation’s serious long-term fiscal imbalances.