- Home

- Unpacking The Tax Cut-Unemployment Compr...

Unpacking the Tax Cut-Unemployment Compromise

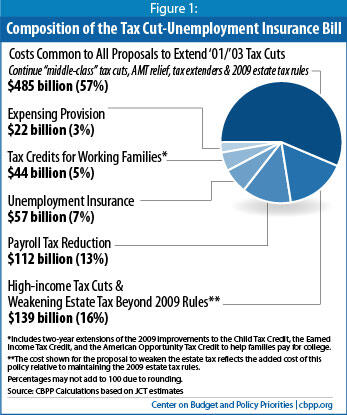

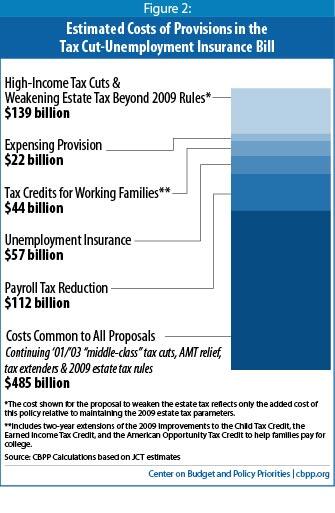

Last night, the Senate released legislative language for the tax cut-unemployment insurance compromise negotiated between President Obama and Congressional Republicans. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) released an official cost estimate for the revenue portions of the bill shortly thereafter. These graphs illustrate the various components of the legislation and their costs.

Costs common to all proposals for extending the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts. This category includes provisions that both parties had already called for extending before the compromise was reached: $384 billion for extension of the “middle-class” tax cuts and AMT relief, $46 billion to preserve the estate tax at its 2009 rate of 45 percent and exemption level of $3.5 million per person ($7 million per couple), and $56 billion in regular tax “extenders,” mostly for businesses. The compromise extends all of these provisions through 2012, except AMT relief, which is continued through 2011. As we have previously explained, the “middle-class” tax cuts do not benefit only the middle class — high-income households benefit from these provisions, as well.[1]

We count extending the 2009 estate tax rules as a cost common to previous proposals.[2] The House voted last year to continue the estate tax at the 2009 levels (H.R. 4154), and the Senate voted 56-43 to extend the 2009 rules the last time it voted on a budget resolution.

High-income tax cuts and weakening the estate tax beyond 2009 rules. This includes $116 billion for the tax provisions from 2001 and 2003 that benefit only high-income households: the reductions in the top two marginal tax rates (from 39.6 percent to 35 percent

JCT’s cost estimates for extending the lower rates on capital gains and dividends do not distinguish between the portions of those tax cuts that benefit middle-class households and the portions benefiting high-income households. However, the statutory PAYGO legislation passed by Congress in February 2010 did make such a distinction. We used older JCT cost estimates to apportion the $53 billion total capital gains and dividends tax cuts into “middle-class” tax cuts ($18 billion, counted as a cost common to all proposals for extending the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts) and high-income tax cuts ($35 billion). The $35 billion in high-income capital gains and dividends tax cuts are included among the high-income tax cuts.

Payroll tax reduction. This is the 2 percentage point reduction in the payroll tax included in the compromise. (The payroll tax reduction would in some sense replace the expiring Making Work Pay tax credit.)

Tax credits for working families. This includes a two-year extension of the 2009 improvements to several tax credits benefiting low- and moderate-income families: $20 billion for the improvement to the Child Tax Credit, which particularly helps working parents earning the minimum wage or just above; $7 billion for improvements to the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) that reduce the marriage penalty for low-income couples and provide families with three or more children with a modestly larger credit; and $18 billion for the American Opportunity Tax Credit, which helps lower- and middle-income families pay for college.

Expensing provision. This provision would extend 100 percent bonus depreciation (expensing) for capital purchases through the end of 2011, and allow businesses to take 50 percent depreciation for such purchases in 2012. JCT estimates that expensing would cost about $110 billion in 2011 and 2012, but that the federal government will recoup all but $22 billion through higher revenues in 2013 through 2020. The provision essentially accelerates tax deductions that firms would have taken in subsequent years.

High-Income People Would Benefit Significantly From Extension of “Middle-Class” Tax Cuts

End Notes

[1] See Chuck Marr and Gillian Brunet, “High-Income People Would Benefit Significantly From Extension of ‘Middle-Class’ Tax Cuts,”Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 13, 2010.

[2] We used older JCT cost estimates for extending the 2009 estate-tax rules and for the estate-tax provisions in the compromise to apportion the total $68 billion cost for the new legislation’s estate-tax provisions between the proposal to maintain the tax at under its 2009 parameters and the provisions of the compromise that weaken the tax beyond that.

More from the Authors