Chairman Brown, Ranking Member Toomey, members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify before you this morning at this important hearing. I am Peggy Bailey, Vice President for Housing Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan research and policy institute in Washington, D.C.

In this testimony, I will discuss the pressing housing affordability crisis affecting people with the lowest incomes and recommend policies that will move us toward the goal of ensuring that everyone in this country is able to afford safe, stable housing.

Addressing the nation’s affordable housing crisis must include housing subsidies, such as Housing Choice Vouchers, for people with little to no income. These families do not have incomes high enough to afford quality housing because landlords must set rents at least high enough to cover their own operating costs, perform general maintenance, and pay any debt owed. Housing agencies can “project-base” vouchers to guarantee that developments include units affordable for families with low and extremely low incomes. For example, many buildings with units dedicated as permanent supportive housing for people experiencing homelessness who also have disabilities use project-based vouchers to make units affordable for this population. The voucher program can also mitigate the need to build new units by allowing people to remain in modest, decent units that are appropriate to their family size. Voucher holders do not need to move but can have their rent burden reduced, which allows them to afford other basic needs or survive a small financial crisis.

Closing the housing affordability gap will require a long-term strategy but progress can be made in the short term. Most immediately, Congress should fund at least the 140,000 new vouchers included in the 2023 Transportation-HUD funding bill passed by the House Appropriations Committee, together with adequate funding for existing vouchers to cover rising housing costs. As part of that bill, Congress should also provide adequate voucher administrative funding, fund services to help voucher holders search for housing, and allow voucher subsidy funds to be used for security deposits.[1] Over the longer term, lawmakers should enact major additional voucher expansions, with the goal of making vouchers available to everyone who is eligible.

Congress must take additional steps, including:

- Reducing the shortage of deeply affordable rental housing. There is a need to increase affordable rental housing stock through multifamily and manufactured housing developments. Actions such as expanding the capacity of the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit; increasing funding for Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) programs like HOME, the Community Development Block Grant, and the Housing Trust Fund; implementing new strategies such as a renters’ tax credit;[2] and directing more resources for manufactured housing are needed. HUD’s Our Way Home Initiative recognizes the need for a comprehensive strategy to increase housing supply. HUD’s programs often work with the LIHTC to make rents affordable for families with the lowest incomes by subsidizing predevelopment and ongoing operating costs, which helps keep rents lower. Alongside these actions, there’s also a need to address zoning practices and other local actions that can stand in the way of building new affordable housing.

-

Prevent the loss of existing affordable housing. Resources are needed to preserve the existing affordable housing stock along with actions to improve the properties. Estimates are that about 6 percent of the federal assisted housing stock is set to lose affordability restrictions by 2025. Based on past data, about half will likely not stay affordable, resulting in the loss of about 176,000 units in the near term.[3]

Several actions are needed to preserve affordable housing:

- Remove barriers to homeownership. There is a shortage of affordable single-family homeownership opportunities due to a low supply of homes and challenges first-time buyers are facing accessing mortgages. If fewer people can successfully purchase homes, then more people remain in the rental market, creating a shortage of rental units and driving up costs. Down payment assistance for first-time homebuyers and other policies to make it easier for families to obtain mortgages are critical to relieving pressure from the rental market.

- Reform existing public and multifamily housing. Most project-based federal assistance does not allow families to move and maintain their housing subsidy. These programs should be reformed to allow tenants true choice in where they live. This will put pressure on landlords and owners to make their units more attractive and reduce neighborhood segregation of people with low incomes.

- Improve the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program. LIHTC should be reformed to make it easier for states and developers to ensure that more units are affordable to people with incomes well below the program’s eligibility limit (although many low-paid workers and others with extremely low incomes will still need a voucher or other rental assistance to afford these units). This can include amending state Qualified Action Plans to include extra points for projects that will allow people with lower incomes to rent units and dedicating federal or state resources that reduce the predevelopment costs for developers.

- Address housing needs in tribal communities. Increase resources for Native American housing programs, particularly the Indian Housing Block Grant, the Indian Community Development Block Grant, and the Native Hawaiian Housing Block Grant, to address the high rates of housing hardship faced by American Indians and Alaska Natives living on tribal lands and Native Hawaiians on the Hawaiian homelands while continuing to honor tribal sovereignty.

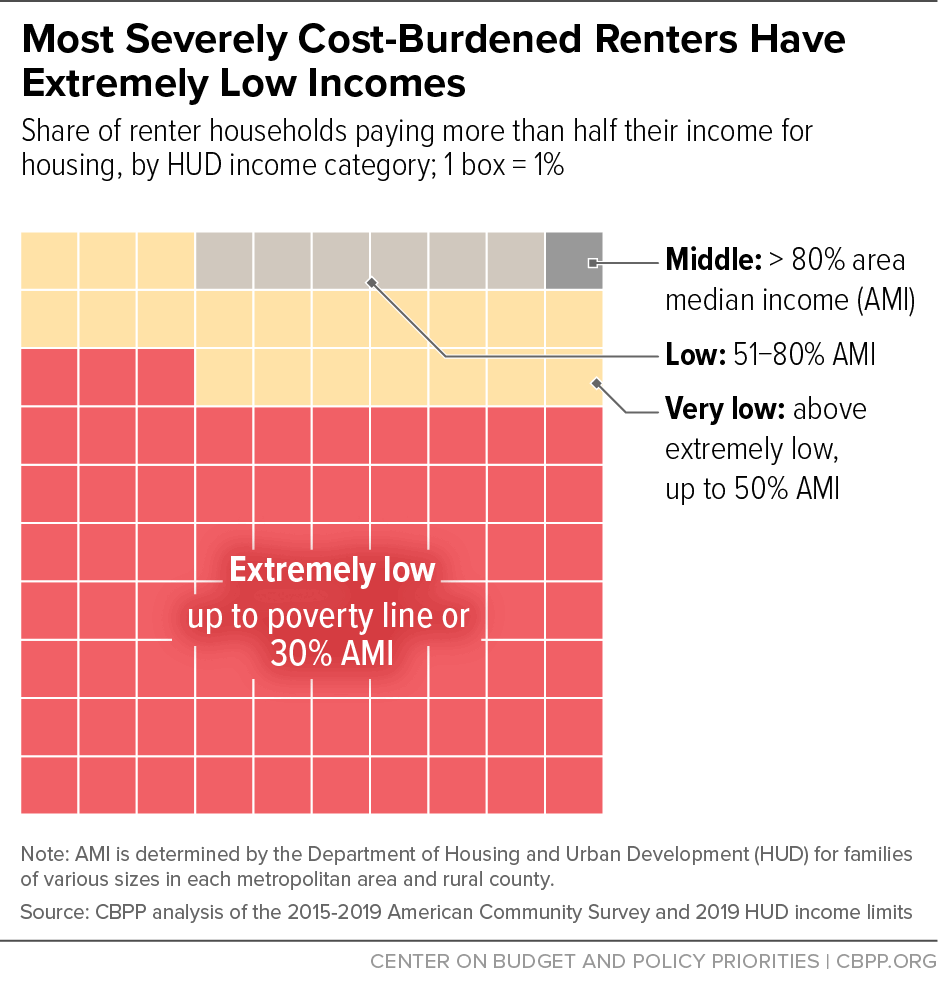

The nation’s most pressing housing problem centers on the millions of people with low incomes who are not able to afford safe, stable housing. This often is characterized as a problem due to the supply of hard units. While supply is an issue in some places, it is important to recognize that most people have a place to live and are not seeking to move; they simply struggle to afford their current residence. Even before the pandemic and economic downturn, 23 million people lived in 11 million low-income households that paid more than 50 percent of their income for rent. (See Figure 1.) Government programs and private owners and lenders often use 30 percent of income as a benchmark for the amount households can afford to pay for housing.[4]

While most people who need housing to be more affordable already have a place to live, many do not. Unaffordable housing compels many people with low incomes to live in homes that are overcrowded or unsafe, and hundreds of thousands of people can’t afford a home at all; 580,000 people slept in shelters or on the streets on the night in January 2020 when HUD conducted its annual point-in-time homeless count.

These affordability challenges are becoming increasingly urgent for many people around the country for two reasons:

- First, rent and utility costs have risen sharply since the summer of 2021. By June 2022, rents for newly leased units were 15 percent higher than a year earlier, according to one national index.[5] And in the 12 months through June, prices for residential fuel and utilities rose 18 percent. Typically, renters who must pay very high shares of their income for housing have to divert money away from other necessities to keep a roof over their heads, such as by going without needed food, medicine, clothing, or school supplies. As those unmet needs pile up, families often find themselves one setback — a cut in their work hours or an unexpected bill — away from eviction. In March 2022, 10.4 million adult renters reported that they were not caught up on rent.[6] Inflation can make this problem more acute.

- Second, many states and localities are beginning to exhaust the Emergency Rental Assistance funding provided through pandemic relief legislation. This assistance has helped at least 5.7 million households pay rental debt accumulated during the pandemic and accompanying economic downturn and to afford ongoing rent and utility costs. The exhaustion of these funds will eliminate a key source of help for people struggling to stay housed.

Difficulty affording housing is heavily concentrated among households at the bottom of the income scale. More than 70 percent of households that pay over half their income for rent have extremely low incomes (defined by HUD as below the federal poverty line or 30 percent of the local median income, whichever is higher), and these households are far more likely than higher-income households to experience homelessness and other housing-related hardship. Nearly everywhere in the country, rents are too high to be affordable to people with the lowest incomes, including low-paid workers[7] and seniors and people with disabilities with low fixed incomes.[8]

Due to a long history of racial discrimination in housing and other areas, these problems are disproportionately concentrated among people of color. As a result, people of color are already more likely to rent their homes because they have historically been denied homeownership opportunities; 55 percent of renters identify as a race other than white, compared to 39 percent of the general population.[9]

People of color are also more likely to face housing hardship, instability, and homelessness. More than 60 percent of people in low-income households that pay more than half their incomes for housing are people of color. These renters are more likely than white renters to live in crowded conditions. Asian and Pacific Islander and Latino renters face the highest levels of doubling up and overcrowding, with 1 in 10 living in households that are both doubled up and overcrowded.[10] And people of color are at much greater risk of experiencing homelessness. Nearly 40 percent of those who experienced homelessness in 2020 were Black and 23 percent were Latino, far above these groups’ shares of the U.S. population (13 and 18 percent, respectively). Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders have the highest rate of homelessness, followed by American Indians and Alaska Natives.[11]

Rental assistance programs play a crucial role in closing the affordable housing gap and preventing housing instability, including homelessness, evictions, and overcrowding.

Federal rental assistance helps 10 million people in 5 million households afford housing, mainly through three major programs: Housing Choice Vouchers, Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance (PBRA), and public housing. In each of these programs, participants pay about 30 percent of their income for rent and utilities and a federal subsidy covers the remaining costs. Because of inadequate funding, these programs, along with several other programs administered by HUD and some by the Department of Agriculture, only assist about 1 in 4 households in need,[12] and most applicants for rental assistance face waiting lists that are very long or closed.[13]

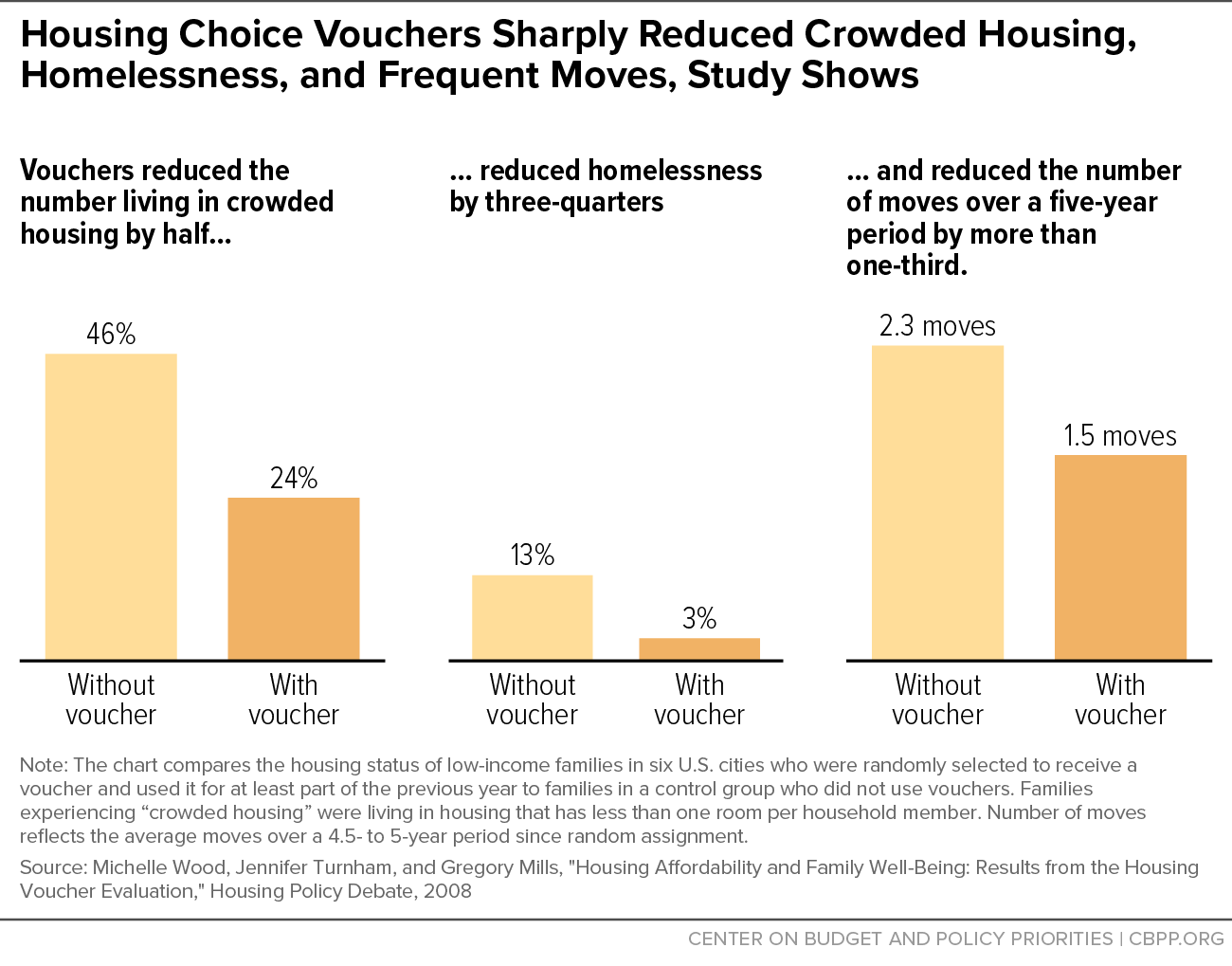

Rental assistance is by far the most direct, effective way to address the nation’s most severe housing problems. Research shows that vouchers sharply reduce homelessness, overcrowding, and housing instability. (See Figure 2.) And because stable housing is crucial to many other aspects of a family’s life, those same studies show numerous additional benefits to vouchers. Children in families with vouchers are less likely to be placed in foster care, switch schools less frequently, experience fewer sleep disruptions and behavioral problems, and are likelier to exhibit positive social behaviors such as offering to help others or treating younger children kindly. Among adults in these families, vouchers reduce rates of domestic violence, drug and alcohol misuse, and psychological distress.[14]

Expanding rental assistance can also sharply reduce racial disparities in poverty rates and a range of housing hardships. For example, one study estimated that providing vouchers to all eligible households would lift 9.3 million people above the poverty line, using a measure of poverty that counts in-kind benefits such as rental assistance as income. Poverty rates would drop for all racial and ethnic groups but most among Black and Latino households, reducing the gap in poverty rates between Black and white households by one-third and the gap between Latino and white households by nearly half.

Similarly, people of color would be particularly likely to benefit from the reductions in homelessness, overcrowding, and evictions and other housing instability that the added vouchers would bring about.[15] Moreover, resources for tribal housing programs, such as the Indian Housing Block Grant, would be particularly helpful for reducing housing hardship in tribal areas. American Indians and Alaska Natives living on tribal lands face higher rates of overcrowding and substandard housing,[16] compared to the national average, but tribes are ineligible for vouchers and other HUD rental assistance programs.

Racism has also prevented many people of color from choosing what community or neighborhood to live in, as federal, state, and local policies ranging from discriminatory lending rules to exclusionary zoning that prevented development of low-cost housing have blocked Black people and others from moving to areas with predominantly white populations. Moreover, due to neglect by public officials and other factors, many neighborhoods with large shares of people of color suffer from high poverty rates, poorly performing schools, unhealthy environmental conditions, and lack of other services and amenities. Despite anti-discrimination measures such as the 1968 Fair Housing Act, housing discrimination and local government practices that continue to drive investment away from communities of color remain widespread.

Housing vouchers can provide people with low incomes — including people of color — with more choice about where they live. Families with vouchers are much more likely — in one study, nearly four times as likely — to be able to move to low-poverty neighborhoods if they receive mobility assistance.[17] But currently, programs like PBRA, public housing, and the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit don’t automatically provide assistance to tenants if they’d like to move to a new building or community. These families, if they qualify, must be placed on the local housing voucher waiting list, which can be years long. But even without any special assistance, among Black children in households with incomes below the poverty line, children whose families use a voucher are twice as likely as children overall to live in a neighborhood with a low poverty rate.

The voucher program has long used nearly every dollar of funding it receives, so the number of families it helps is limited primarily by inadequate funding, not by a shortage of units. From 2011 to 2020, housing agencies on average spent 99.9 percent of the voucher subsidy funds they received. (This figure excludes agencies participating in the Moving to Work demonstration, which allows agencies to shift voucher funds to other purposes.)[18] This percentage dipped during 2021 in the face of an unusually tight rental market, but agencies still used an average of over 96 percent of their funds, and many individual agencies used all or nearly all of their voucher funds. Agencies would be able to use many additional vouchers if they received the funds to do so, particularly if new resources are targeted toward agencies that have high utilization rates today.

Most households that receive a voucher (two-thirds, in one study) already rent a housing unit, so their vouchers do not add to the number of units demanded in the market.[19] Typically, these households paid very high shares of their income for rent before receiving the voucher, and some use the voucher to help them afford their current unit without diverting resources from other basic needs. (The voucher also helps protect them from eviction if their earnings drop or they face unexpected expenses.) More than 8 million extremely low-income households have a home but spend more than half their income to rent it, so many vouchers could be absorbed simply by helping those households either to stay in their current housing or to move to a more suitable unit (such as one that provides adequate space given the household’s size or is closer to a worker’s job), thus freeing up the household’s current unit for another household to occupy.

New vouchers would also help people who don’t have their own unit, such as those living in a shelter or on the streets or who are doubled up with another family. But most rental markets could absorb many such households just as they absorb other new renters, such as young adults leaving their parents’ homes or workers relocating to pursue a job opportunity. Rental markets in some parts of the nation have sizeable numbers of vacant units,[20] and even relatively tight markets could likely absorb the vouchers on the scale proposed in recent legislation (such as the 140,000 vouchers funded in the 2023 Transportation-HUD appropriations legislation passed by the House Appropriations Committee) because the number of units needed would be low compared to the overall housing stock.

In fact, the Emergency Housing Voucher (EHV) program, funded through the American Rescue Plan Act, demonstrates housing agencies’ ability to use new vouchers, even in tight rental markets. So far, the program has helped more than 26,000 households who were experiencing or at risk of homelessness or who were survivors of domestic violence. Those receiving EHVs on average have an income of $11,349, which is about 27 percent less than the typical voucher household.[21] The success of this program demonstrates that additional rental assistance can be used and provides some lessons on how to work with community partners and use administrative fees to make the program more effective.

Policymakers should also make vouchers easier to use and expand choice for voucher holders, for example by allowing voucher subsidies to be used for security deposits, ensuring that voucher subsidy caps (which are set based on Fair Market Rent levels determined by HUD for metropolitan areas, rural counties, and zip codes around the country) are adequate to cover rising rent and utility costs, funding services to help families search for housing in a wide range of neighborhoods, conducting outreach to landlords to encourage them to participate in the program, and prohibiting landlords from discriminating against voucher holders.

Measures to Build and Preserve Housing Also Play an Important Role in Addressing Housing Need

Rental assistance won’t solve those problems alone, and should be part of a broader, comprehensive policy.

Many parts of the country face serious housing shortages, estimated at 3.8 million units by one study, that drive up home prices and rents and limit the housing options available to families and individuals and that could be addressed through a range of subsidies and regulatory changes to expand the housing stock.[22] In some parts of the country, there is an urgent need for investments to address housing quality problems in the existing housing stock, including serious health concerns such as lead paint. The nation’s stock of public housing and to a lesser extent its privately owned affordable housing face large backlogs of unmet renovation needs that can place residents at risk and ultimately result in the loss of badly needed affordable housing.[23]

Investments in the housing stock can further other important goals as well. Housing construction and renovation can play a key role in community development efforts that improve quality of life in the surrounding neighborhoods, including in urban neighborhoods affected by redlining and disinvestment, rural areas suffering from declining populations and economies, and tribal areas that often face severe problems with overcrowding and substandard housing. Supply-side investments can also increase the number of units accessible to people with disabilities and improve energy efficiency in ways that can potentially reduce costs, make units safer and more comfortable for residents, and reduce emissions of greenhouse gases and other pollutants.

In allocating resources for housing renovation and development, policymakers should prioritize investments that benefit the lowest-income people and other underserved groups, including the National Housing Trust Fund, Public Housing Capital Fund, and tribal housing programs. The great majority of households that pay very high shares of their incomes for housing have extremely low incomes — below half of the median income and nearly all below 80 percent of median income — so policymakers should generally not use scarce funding for supply efforts that will benefit households with incomes above that income level. Policymakers can, however, help make housing more affordable for both low- and moderate-income households through reforms to state and local zoning rules and other regulations that constrain the amount of new housing that is built in many areas.

Funding for Native American housing programs is also critical for advancing equity because they are the main resource for affordable housing for American Indians and Alaska Natives living in tribal areas and Native Hawaiians on the Hawaiian homelands. To respect sovereignty, tribal governments get federal housing funding through separate HUD grants, such as the Indian Housing Block Grant and the Indian Community Development Block Grant, instead of through Housing Choice Vouchers, public housing, and many other HUD programs. Similarly, the Native Hawaiian Housing Block Grant helps eligible Native Hawaiians with low incomes live on their homelands.

And while state-level allocations of the National Housing Trust Fund or the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit could be used to build or rehabilitate housing on tribal lands, such projects would have to compete with those in the rest of the state under structures not designed to address land-use barriers specific to tribal areas. Some 68,000 new homes are needed to eliminate overcrowding and replace inadequate housing on tribal lands, according to one 2017 estimate.[24] Funding for tribal housing development and assistance programs, however, has remained relatively flat since the 1996 enactment of the tribal housing law. Annual Indian Housing Block Grant appropriations haven’t kept pace with inflation, although Congress has provided some helpful increases in the past few years.[25]

While investments in housing construction and renovation are important, unless a household also receives a voucher or other similar ongoing rental assistance, construction subsidies rarely produce housing with rents that are affordable for households with incomes around or below the poverty line. Since most households that pay over half their income for rent or that experience homelessness have extremely low incomes, it is critical that supply investments are married with rental assistance investments. The supply investments can help create more affordable housing and the rental assistance can then fill the gap between what families with very low incomes can afford and the cost of units defined as “affordable.”

One reason supply investments alone are rarely enough to enable the lowest-income households to afford housing is that these households typically can’t afford rent set at a high enough level for an owner to cover the ongoing cost of operating and managing housing. The average extremely low-income renter household had an income of $11,318 in 2019, the latest year for which data are available.[26] As explained above, government programs and private-sector owners and lenders often consider housing affordable if it costs no more than 30 percent of household income, which for this household works out to $283 a month for rent and utilities. Many households, including those most at risk of homelessness, have much lower incomes and can afford even less in rent. But in 2019 the average market rental unit’s operating cost was $520 a month (over $580 when the owner paid for utilities), according to National Apartment Association data.[27] By 2020, these figures had increased to $534 without utilities and $614 with utilities, and these figures have surely risen substantially since then.[28] Consequently, even if development subsidies pay for the full cost of building housing, rents in the new units will generally be too high for lower-income families to afford without the added, ongoing help a voucher can provide.

The largest federal affordable housing development program, the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, illustrates this. LIHTC allows rents to be set up to levels affordable to families with incomes at 60 percent of the local median, more than 200 percent of the poverty line in many areas. Fortunately, LIHTC developments house many families with incomes around or below the poverty line, but nearly all of those families either pay high shares of their income for rent or receive a voucher or similar rental assistance that enables them to afford the unit.[29] If policymakers expand LIHTC or other development subsidies but do not adequately expand rental assistance, there will be a serious risk that many of the families who struggle most to keep a roof over their heads will not be able to afford the new homes.

Vouchers can help reduce rents to affordable levels for families with low incomes in two ways. First, most vouchers are tenant-based, meaning they can be used in a modest unit of the family’s choice. Federal law prohibits owners of most buildings that receive federal development subsidies from discriminating against voucher holders, so a family with a tenant-based voucher could opt to use it in such a development or elsewhere.

Second, housing agencies can also enter into long-term project-basing agreements that require some vouchers to be used in a particular development. A family living in a project-based voucher unit is permitted to move with the next available tenant-based voucher after one year, and a new family from the voucher waiting list then moves into the project-based voucher unit. Project-based vouchers can play a useful role, for example by enabling housing agencies to enter into long-term agreements ensuring that some units are available to voucher holders in neighborhoods where vouchers are otherwise difficult to use, or for supportive housing that provides rental assistance together with services for people with disabilities or with a history of homelessness. In addition, a long-term project-based voucher contract can help finance affordable housing development, since a portion of the voucher subsidies can be used to pay back debts incurred during construction.

Agencies can project-base up to 30 percent of their vouchers with exceptions allowing agencies to go higher under certain circumstances. Only a few dozen of the nation’s 2,100 voucher agencies are approaching the 30 percent limit once those exceptions are considered, so nearly all agencies could project-base many additional vouchers to make units in new developments affordable to people with the lowest incomes, without additional funding or any change to current law. (Other project-based subsidies such as public housing and PBRA can play a similar role, but don’t allow families to move, as project-based vouchers do. Policymakers should consider extending this option and some other characteristics of project-based vouchers to public housing and PBRA, particularly if they opt to expand either of those programs.)

It is important, however, that most vouchers remain tenant-based and that any housing investment package sharply expand the voucher program as a whole so that housing agencies can increase the availability of both tenant-based and project-based vouchers. Tenant-based vouchers are essential to ensuring that federal housing investments allow low-income people to choose where they live. A housing investment package focused solely on development or on project-based rental assistance would limit the housing choices available to low-income renters (who are disproportionately people of color). Those families would receive help to rent a particular unit but would usually have to give up their subsidy if they need to move elsewhere (for example, to be close to a job opportunity, to a relative who can act as a caregiver, or to a school they would like their child to attend). Tying most rental subsidies to particular units would repeat a mistake housing policymakers made in the past, particularly during the establishment and expansion of the current public housing and PBRA programs.

This risk from limiting choice is compounded by a long history of discriminatory housing policies that have contributed to the segregation of low-income people, especially Black families, into poorer communities with under-resourced schools and other disadvantages. That history has been reinforced by ongoing resistance to affordable housing development in many predominantly white neighborhoods.[30] It is critical that new housing supply and rental assistance investments not reinforce these patterns. Policymakers could avoid this by seeking to locate new affordable housing developments in neighborhoods that offer residents good opportunities and quality public services and encouraging developments that serve households with a mix of income levels. But coupling investments in affordable housing development with a major voucher expansion can help too, by making it easier for people with low incomes to move to a different neighborhood if they wish.

Immediate action is critical. The Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University and other industry leaders recognize that, while many parts of the country continue to experience housing shortages, through early 2022 we have been in a housing development boom as markets respond to those shortages. New housing starts are reaching levels we haven’t seen since the 1990s.[31] However, these new rental housing developments are largely targeted at the upper end of the housing market. The average asking rent for new units in 2021 was $1,740 per month, but the median renter could only afford $1,080 per month. These new developments are targeted to this segment of the rental market partly because of these renters’ inability to move to homeownership, and, absent government action, will not be affordable for even families with moderate incomes. Yes, it may take several years for these new projects to begin to be occupied but now is the time to add rental subsidies, incentives, or contract requirements that ensure a significant amount of these units will be affordable.