Tens of millions of people around the country struggle to afford safe, adequate housing. In 2019, 23 million people lived in households with low incomes that paid more than half of their income for rent and utilities.[1] And sharply rising rents and utility costs in recent months as well as continued employment uncertainty for some due to the pandemic have made it even more difficult for many renters to afford housing. Households with unaffordable housing costs risk homelessness, eviction, overcrowding, and living in substandard housing — conditions that can compromise their health and safety — and are often forced to cut back on necessities like food and medicine in order to pay the rent. Well-designed rental assistance programs such as Housing Choice Vouchers have proven highly effective at reducing homelessness and other pressing housing problems but have never received anywhere near the funding required to meet the need.

The House-passed Build Back Better legislation contains more than $170 billion in housing investments to begin to address this unmet need. The legislation includes funds for about 300,000 new housing vouchers, a particularly urgent measure right now because vouchers could quickly reduce the cost of housing for renters who receive them, at a time when rents are surging in much of the country. It also includes other housing investments that would benefit households with the greatest need, including affordable housing development through the national Housing Trust Fund and badly needed renovations to the nation’s public housing.

As lawmakers seek a compromise agreement on Build Back Better, they should retain meaningful investments in vouchers and other well-targeted housing assistance, which would substantially reduce some of the most severe hardship that exists in the United States today.

Large numbers of low-income people struggle to afford housing in every state and in rural, suburban, and urban areas. Difficulty affording adequate housing is also widespread among low-income people of all racial groups, but it is disproportionately common among people of color due to a long history of discrimination in housing, employment, and other areas. More than 60 percent of people experiencing homelessness and more than 50 percent of people in low-income renter households who pay over half their income for rent and utilities are Black or Latino, even though those groups make up just 31 percent of the overall population.

Households who pay a large share of their income for housing must typically shift money from other basic needs such as food, medicine, and clothing to help pay the rent. Many are just one setback away — a reduction in work hours or unexpected expense such as a needed car repair, for example — from losing their homes. According to survey data collected between December 29, 2021 and January 10, 2022, over 11.5 million adult renters were behind on rent, and nearly half of them reported that they were either very or somewhat likely to face eviction in the next two months.

High housing costs also force many renters to live in overcrowded or substandard homes. These conditions can place residents’ health and safety at risk, as was demonstrated tragically by fires in overcrowded buildings in New York City and Philadelphia during January 2022 that killed 29 people, including 17 children. And many people can’t afford housing at all. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) estimates that 1.45 million people experienced sheltered homelessness (meaning they stayed in emergency shelters, safe havens, or transitional housing) at some point during 2018, the most recent year for which data are available. [2] HUD’s annual single-night count in January 2020 found that more than 580,000 people were homeless.

Each of these housing problems — high rent burdens, housing instability, overcrowding, substandard housing, and homelessness — has been linked to serious adverse effects on children’s health and development. And each affects a large number of children around the country. For example, children under 1 year old experience sheltered homelessness at a higher rate than any other age group.[3] And during the 2019-2020 school year 1.3 million school-age children lived doubled up with another family (often in unstable and overcrowded housing arrangements), in shelters or hotels, or on the streets.[4]

Emergency rental assistance enacted through December 2020 funding legislation and the March 2021 American Rescue Plan has provided urgently needed help to households struggling to pay rent and utilities due to the pandemic and accompanying economic disruptions. But this funding will only cover part of the unmet need for rental assistance and only temporarily, so it is not an alternative to longer-term expansions of programs such as Housing Choice Vouchers. Some states and localities have already stopped providing emergency rental assistance to new families because they have allocated all their funds, and the program will exhaust its funding by late 2022 if it continues to provide assistance at its current pace nationally.

Moreover, most rental assistance provided through the relief bills is only permitted to cover 18 months of rent and utility costs (including both ongoing costs and unpaid bills from prior months).[5] The assistance wasn’t widely available until 15 months after the pandemic began, so many families may use it mainly to repay rent and utility debt rather than to cover ongoing costs. But many low-income renters — such as workers earning low wages and seniors and people with disabilities with low fixed incomes — will likely continue to struggle to afford housing going forward, particularly in the face of sharply rising rent and utility costs.

High levels of housing-related hardship do not need to continue. In most similarly wealthy countries, a far lower share of renters pay over half their income for housing than in the United States.[6] And in this country, rental assistance programs have proven highly effective at enabling people with low incomes to afford housing and could greatly reduce homelessness and other pressing housing problems if more adequately funded.

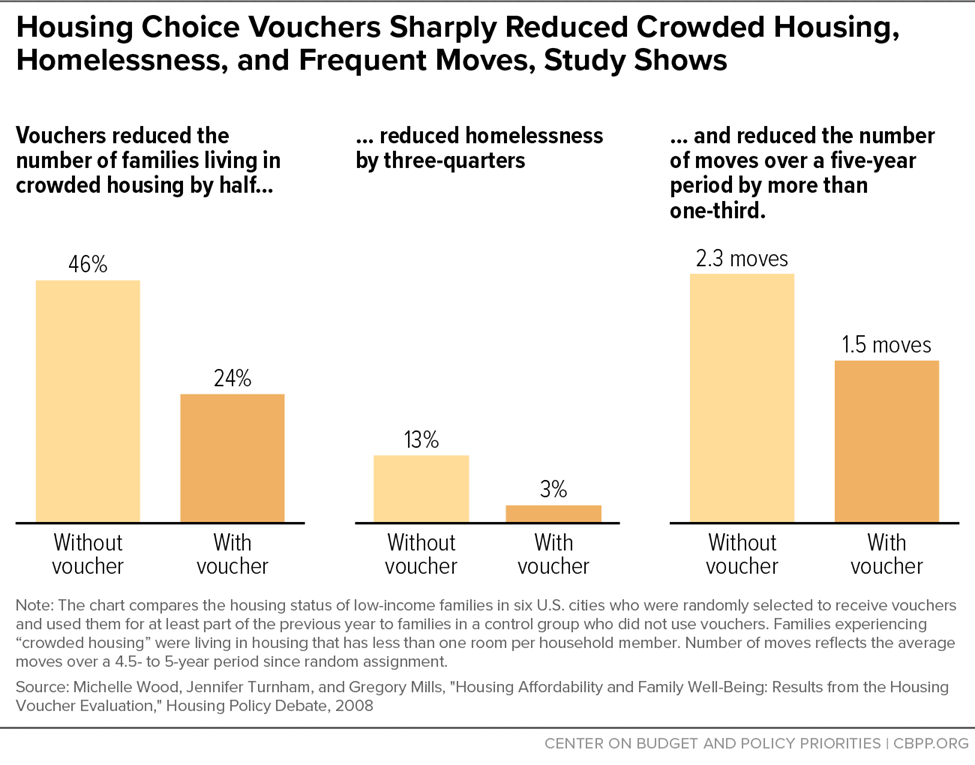

Rigorous research finds that Housing Choice Vouchers, which help people with low incomes rent modest housing of their choice in the private market, sharply reduce homelessness among families with children. (See Figure 1.) Because stable, uncrowded housing is crucial to many aspects of a child’s life, studies also show that they have numerous other benefits. Children in families who received vouchers are less likely to be placed in foster care, switch schools less frequently, experience fewer sleep disruptions and behavioral problems, and are likelier to exhibit positive social behaviors such as offering to help others or treating younger children kindly. Vouchers also give families greater choice about where they live; when families use vouchers to move to lower-poverty neighborhoods, their children are more likely to attend college and earn more on average as adults.[7]

Vouchers also reduce homelessness and provide stable, affordable housing for households without children, including many seniors and people with disabilities, who often face serious housing affordability and access challenges.[8] In addition, by lowering households’ rental costs, vouchers and other rental assistance leave them with more resources for other basic needs such as food or clothing. Rental assistance lifted more than 2.4 million people above the poverty line in 2020 under the federal government’s Supplemental Poverty Measure, which (unlike the official measure) counts non-cash benefits (like rental assistance) as well as cash income. Those lifted above the poverty line included 468,000 seniors and 785,000 children.[9]

Despite these proven benefits, only 1 in 4 eligible households receive federal rental assistance due to funding limitations. (See Figure 2.) As a result, there are long waiting lists for assistance across the country — so long in some places that housing agencies have stopped taking applications.[10]

The House-passed Build Back Better bill would provide more than $170 billion for a range of measures to help make housing more affordable. They include $24 billion to expand the Housing Choice Voucher program — enough to fund more than 300,000 additional vouchers once the expansion is fully phased in. Of these vouchers, about 80,000 would be set aside for people who are experiencing or at risk of homelessness and for survivors of domestic violence and human trafficking. The remainder would be available to any extremely low-income households, defined as those with incomes below the federal poverty line or 30 percent of the local median, whichever is higher.

The vouchers in Build Back Better would help nearly 700,000 people in over 300,000 households — including about 274,000 children, 76,000 seniors, and 138,000 people with disabilities — live in stable, affordable homes. The vouchers would lift about 250,000 people, including about 90,000 children, above the poverty line.[11] An estimated 70 percent of those assisted would be people of color.[12] The vouchers would help people in a wide range of communities: 36 percent of vouchers are used in suburban areas and 11 percent in rural areas.[13]

The bill also includes $65 billion to address unmet renovation needs in the nation’s public housing. Public housing provides affordable housing to more than 1.7 million low-income people, but due to a long history of inadequate federal funding, conditions in many developments are deteriorating. Build Back Better’s large investment in public housing would allow local agencies to make urgently needed repairs, improving living conditions for residents and protecting their health and safety. A large majority of public housing residents are children, seniors, or people with disabilities, and close to 70 percent are people of color.[14]

In addition, the bill provides large amounts of funding to build and rehabilitate affordable housing, including $15 billion for the national Housing Trust Fund, $12 billion for the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit, and $10 billion for the HOME Investment Partnership, as well as smaller investments in several other programs. While vouchers alone are sufficient to help many low-income households afford housing and can deliver assistance to them promptly, investments in development and renovation are needed to accomplish many important longer-term goals. These include increasing the housing supply in tight markets, improving energy efficiency, addressing health and safety risks such as inadequate fire alarms and sprinkler systems, and making more units accessible to people with disabilities. Among housing development programs, lawmakers should place the highest priority on funding the Housing Trust Fund because it is more tightly targeted than other programs on providing housing that is affordable to people with the lowest incomes.

The House bill also includes smaller — but still important — funding for other well-targeted programs. These include $1 billion for affordable housing in tribal and Native Hawaiian areas,[15] $1 billion for Project-Based Rental Assistance, and $500 million apiece for the Section 811 and Section 202 supportive housing programs for people with disabilities and seniors, respectively.

If policymakers reduce the housing investments in Build Back Better as part of a compromise agreement, they should prioritize the bill’s funding for programs targeted on renters with incomes around or below the poverty line, including Housing Choice Vouchers, public housing, and the national Housing Trust Fund. Households with incomes at that level are far more likely than households with incomes above the poverty line to struggle to keep a roof over their heads; helping them afford housing would do more to reduce hardship and racial inequity than assistance targeted further up the income scale. Such help would also be very timely given the nation’s large unmet housing needs and high costs, which are expected to persist after the pandemic ends.