Chart Book: Funding Limitations Create Widespread Unmet Need for Rental Assistance

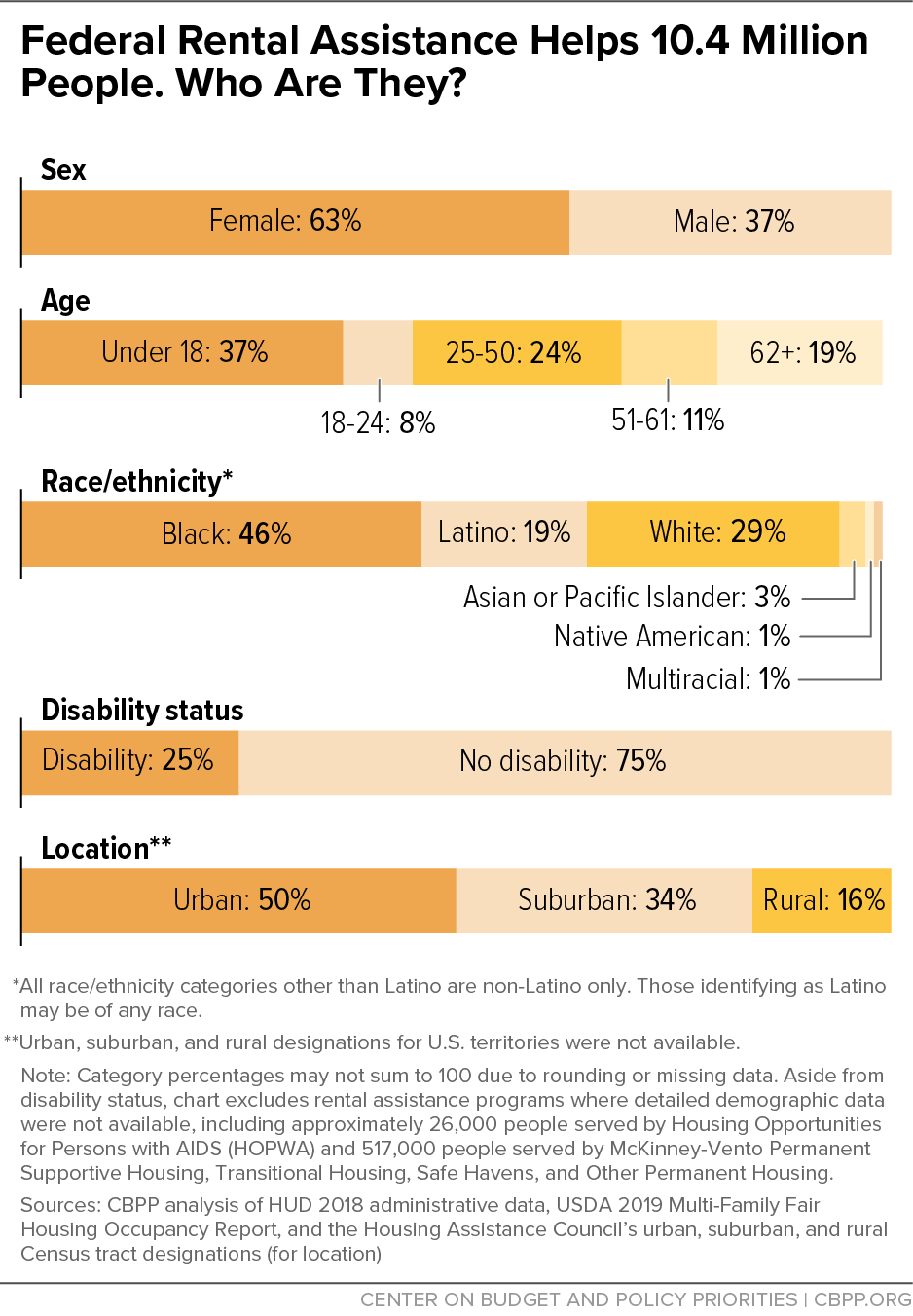

Federal rental assistance enables over 5 million low-income households to afford modest homes. Three major programs — Housing Choice Vouchers, Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance, and Public Housing — assist about 90 percent of households receiving federal rental assistance. Most assisted families pay about 30 percent of their income for rent and utilities, making housing affordable for over 10 million people, including nearly 4 million children.

Federal rental assistance helps families afford decent quality, uncrowded housing and avoid homelessness and other types of housing instability. By limiting housing costs, it also leaves families with more resources for work-related expenses, such as child care and transportation, and basic necessities such as food and medicine. Rental assistance also lifts more than 2.4 million people above the poverty line.

Section 1: Funding Limitations Prevent Rental Assistance From Reaching Renters in Need

Section 2: Rental Assistance Is Underfunded Relative to Need

Section 3: Renters of Color Face Significant Housing Hardship

Section 1: Funding Limitations Prevent Rental Assistance From Reaching Renters in Need

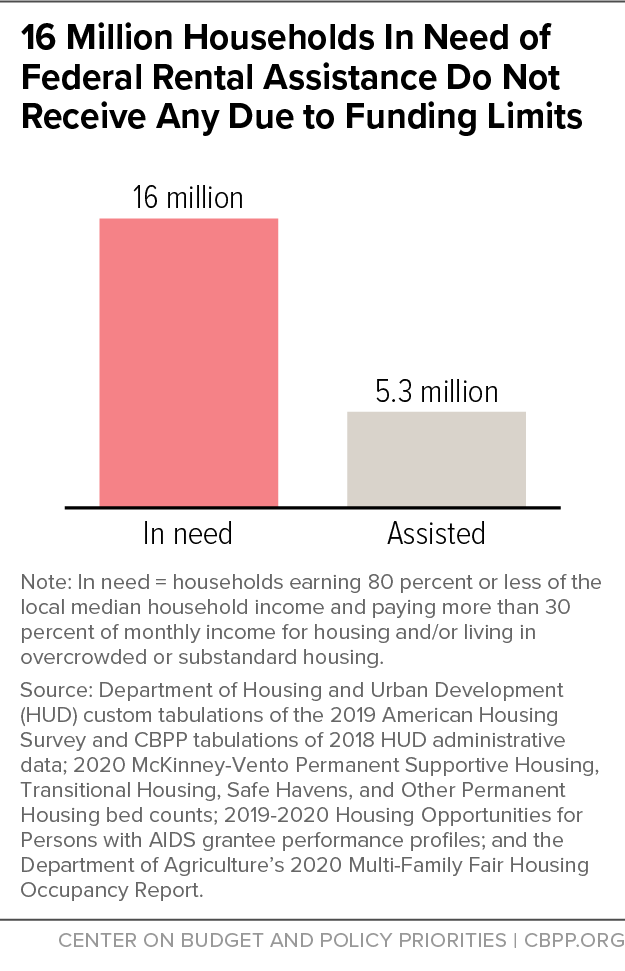

Only 5.3 million (1 in 4) eligible renter households receive federal rental assistance due to funding limitations. Unlike economic security programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), federal rental assistance reaches only a fraction of renters in need. While the number of SNAP participants increases in response to economic downturns, inadequate funding prevents rental assistance from scaling up to meet rising need. This means over 16 million low-income households lack rental assistance, putting them at increased risk of eviction, homelessness, and other forms of housing instability.

Demand for rental assistance far exceeds the amount available due to the limited funding provided by policymakers, which often results in long wait times around the country. Wait times among families who received vouchers average close to two and a half years nationally. Many other eligible families do not receive rental assistance because they never rise to the top of the list or they live in an area where the waitlist is closed. Limited funding also leaves the housing safety net poorly equipped to meet increased need for rental assistance during a crisis, as chronic underfunding caps the number of households that can be assisted.

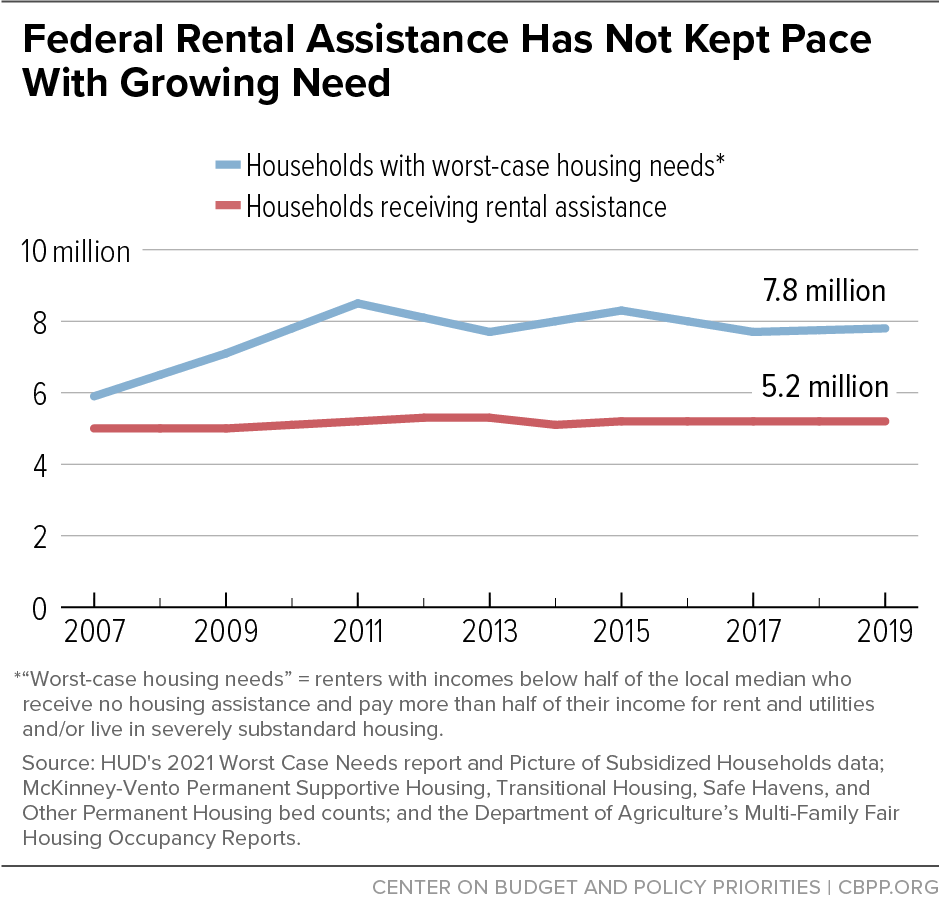

Federal rental assistance has not kept pace with growing need. From 2007 to 2019, the number of renter households with very low incomes either paying more than half their income for rent or living in severely substandard housing, known as worst-case housing needs, increased 32 percent. During this same period, the number of households receiving federal rental assistance rose only 3 percent. In 2020 and 2021, Congress approved substantial emergency rental assistance in response to widespread housing hardship worsened by the pandemic, helping millions of families pay back rent and avoid eviction. The emergency provisions are temporary, however, and most of the funds are on pace to be exhausted by late 2022, so they won’t address the large unmet need for assistance that existed before the pandemic and will likely continue in its aftermath.

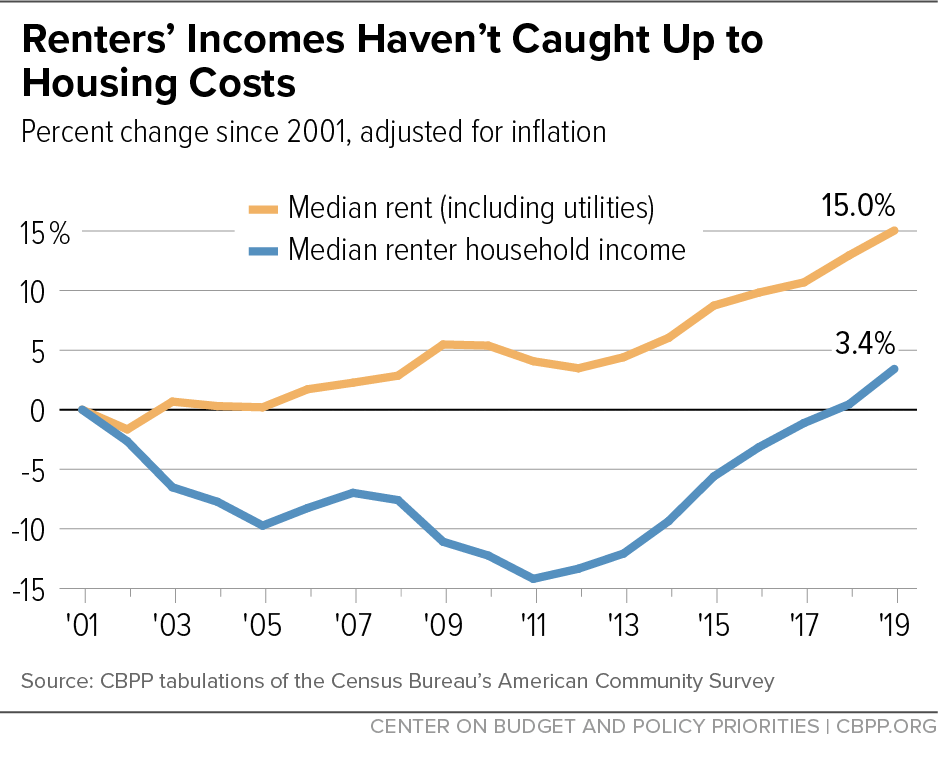

Increasing rents and stagnating wages underlie a housing affordability crisis, driving the growing need for rental assistance. Low-wage workers face a severe shortage of affordable rental units. As a result, many households struggle to pay rent but are unable to get assistance due to funding limitations.

Section 2: Rental Assistance Is Underfunded Relative to Need

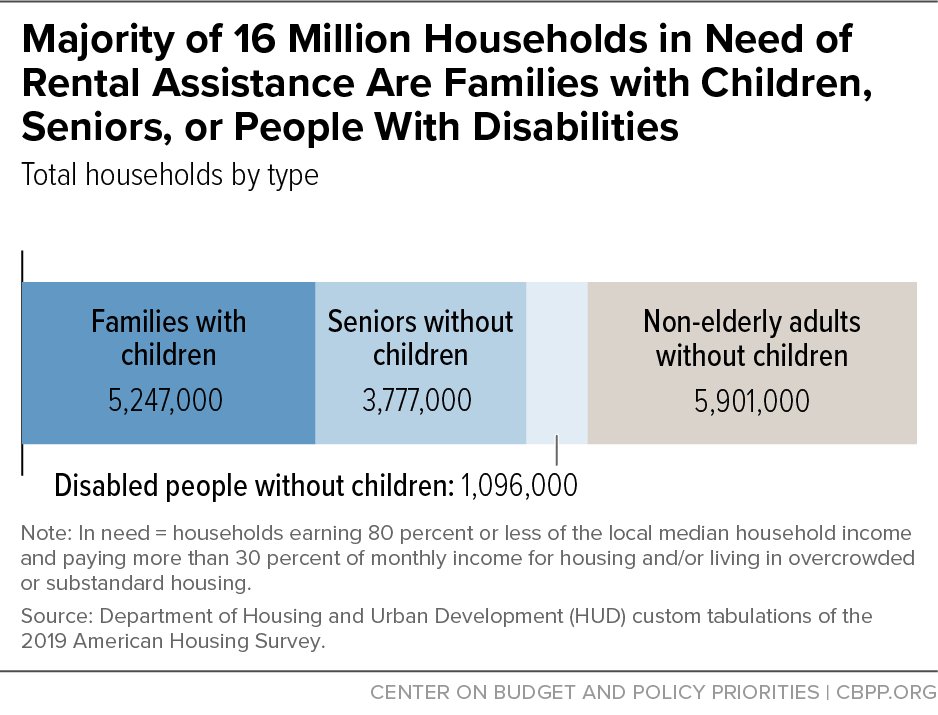

Most households in need of rental assistance are families with children or families headed by a senior or a person with a disability. These households account for 63 percent of the 16 million unassisted renter households, while the remaining 5.9 million households are non-elderly adults without children. Many unassisted households include a working adult yet still struggle to keep a roof over their heads. Excluding households headed by a person with a disability, 88 percent of households headed by non-elderly adults without children and 87 percent of families with children have earnings but still struggle to make ends meet.[1]

Families with children and non-elderly adults without children have the greatest unmet need for rental assistance. The number of assisted families with children has steadily fallen over the past couple decades, despite rising need. That reflects two trends. First, some households continue to receive assistance after their children have grown up or left home. Second, policymakers have provided only a modest number of new vouchers since 2002, and in the last decade nearly all new vouchers have been targeted to homeless veterans and people with disabilities. With stagnant funding leaving fewer resources available, 3 in 4 families with children lack the assistance they need to provide stable homes.

Our nation’s system of economic and health supports is largely geared toward helping children and their parents, people with disabilities, and older adults. This results in a frayed and fragmented system of supports for non-elderly adults without children, including rental assistance. Less than 1 in 10 non-elderly adults without children receive the rental assistance they need to afford housing.

Families With Children and Non-Elderly Adults Without Children Have the Greatest Unmet Need for Rental Assistance

Unassisted vs. assisted households, headed by someone who:

Note: Groups of household types are sized (on left) by number "needing assistance," which means they pay more than 30 percent of monthly income on housing and/or are living in overcrowded or substandard housing. "Low income" = 80 percent or less of median income. For more on how we count assisted renters, please see our federal rental assistance factsheets methodology.

Sources: Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) custom tabulations of the 2019 American Housing Survey and CBPP tabulations of 2018 HUD administrative data; 2020 McKinney-Vento Permanent Supportive Housing, Transitional Housing, Safe Havens, and Other Permanent Housing bed counts; 2019-2020 Housing Opportunities for Persons with AIDS grantee performance profiles; and the Department of Agriculture's FY2020 Multi-Family Fair Housing Occupancy Report.

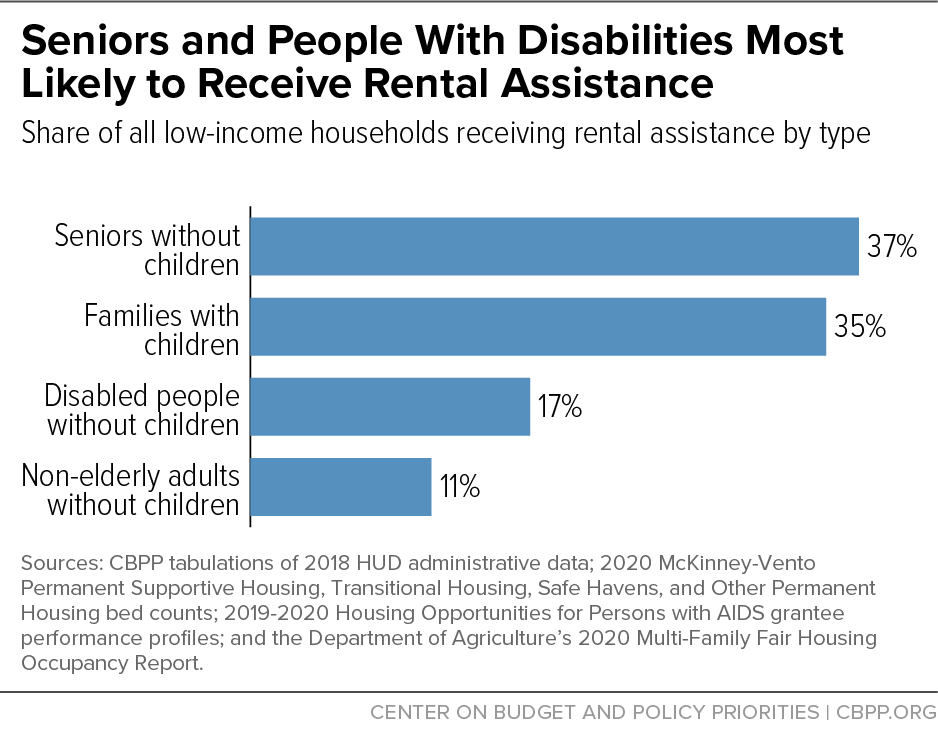

Older adults and people with disabilities are more likely to receive rental assistance than families with children and non-elderly adults without children. This is partly due to rental assistance programs such as supportive housing that are targeted to these populations. Inadequate funding also forces many local housing agencies to prioritize certain groups for limited available rental assistance. An estimated 62 percent of housing agencies have preference systems for their Housing Choice Voucher and public housing programs, often allowing older and disabled applicants to skip long waits for assistance. Once assisted, research shows older adults and people with disabilities tend to stay in assisted housing longer than non-elderly, non-disabled households. While they are more likely to be assisted, older adults and people with disabilities still have significant unmet need for rental assistance, which could be addressed by expanding the Housing Choice Voucher program.

Section 3: Renters of Color Face Significant Housing Hardship

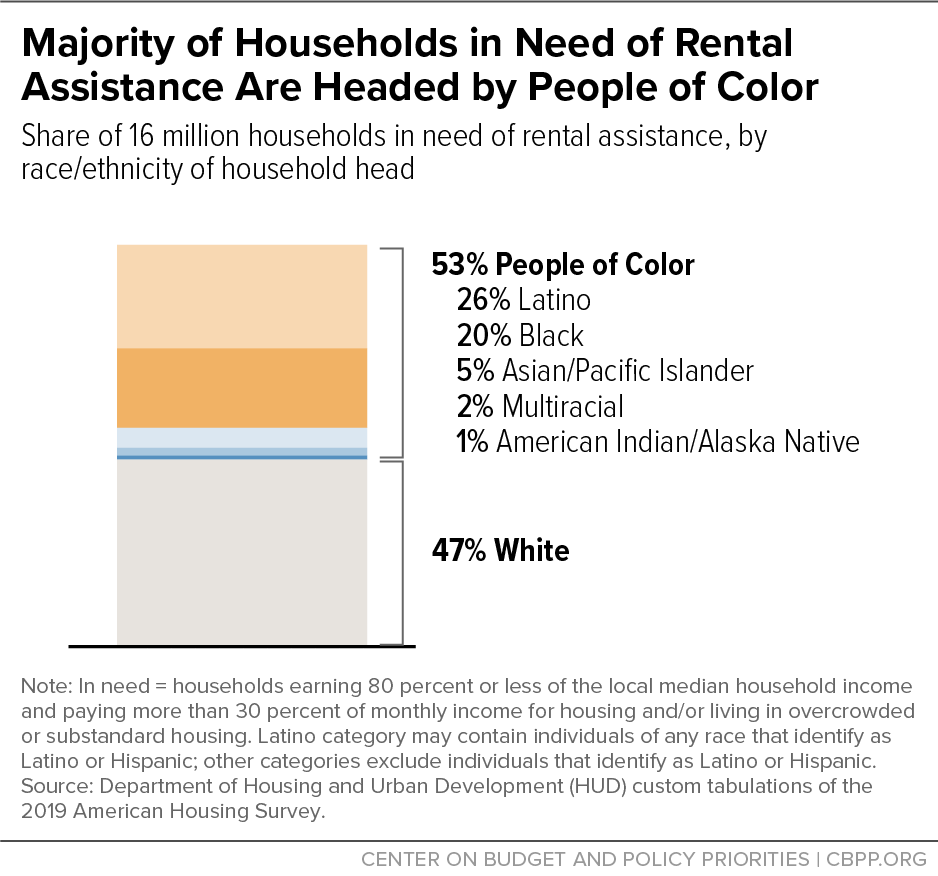

Over half (53 percent) of the 16 million low-income households in need of rental assistance are headed by a person of color. Long-standing inequities often stemming from structural racism in education, employment, and housing leave Black, Latino, and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) households with lower median incomes compared to white households. Racial income inequality causes the housing affordability crisis to disproportionately impact renters of color, and insufficient funding leaves most of these renters without the help they need to close the gap between their wages and housing costs. Addressing this through voucher expansion to all eligible households would cut poverty and reduce racial disparities.

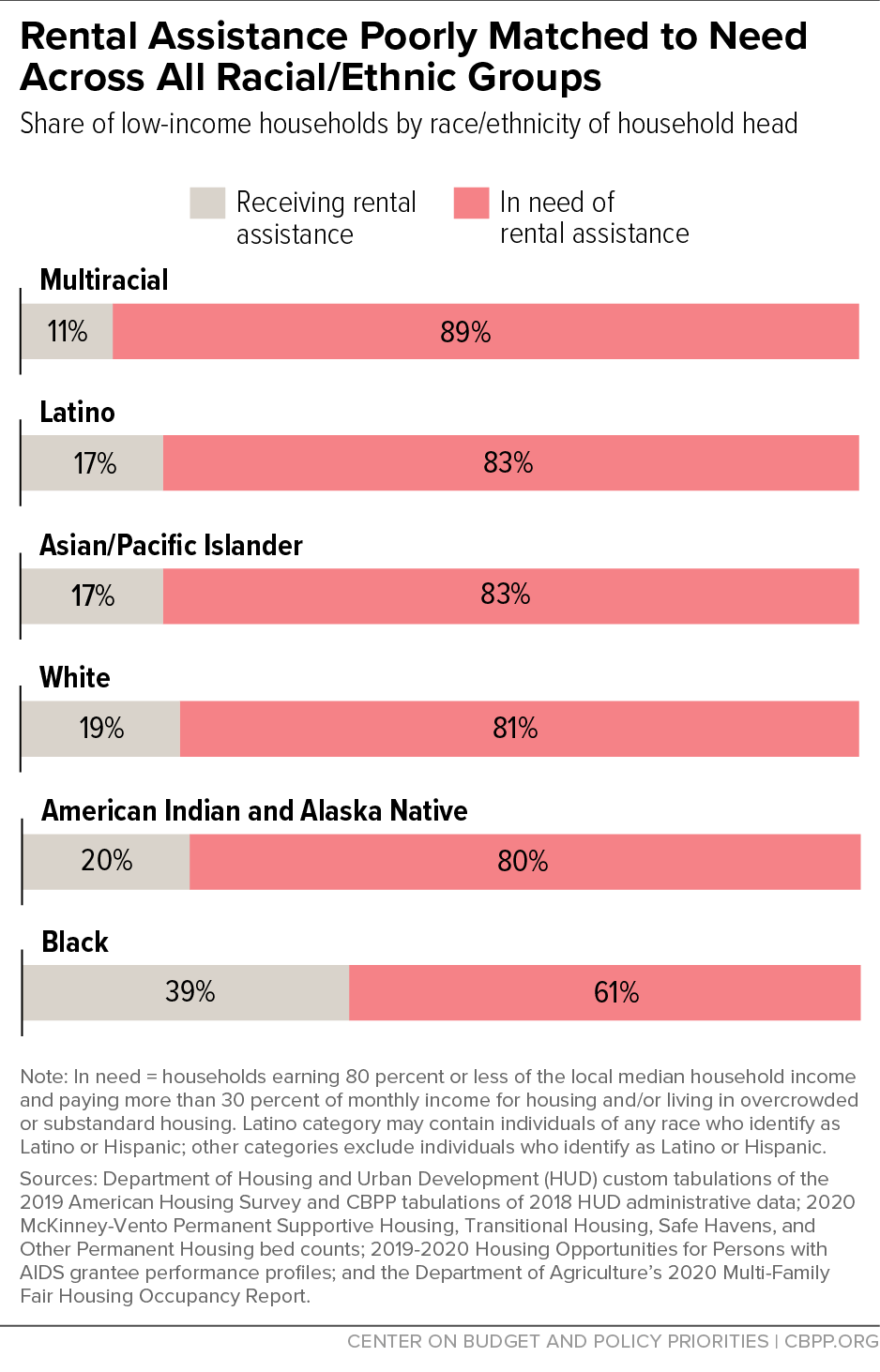

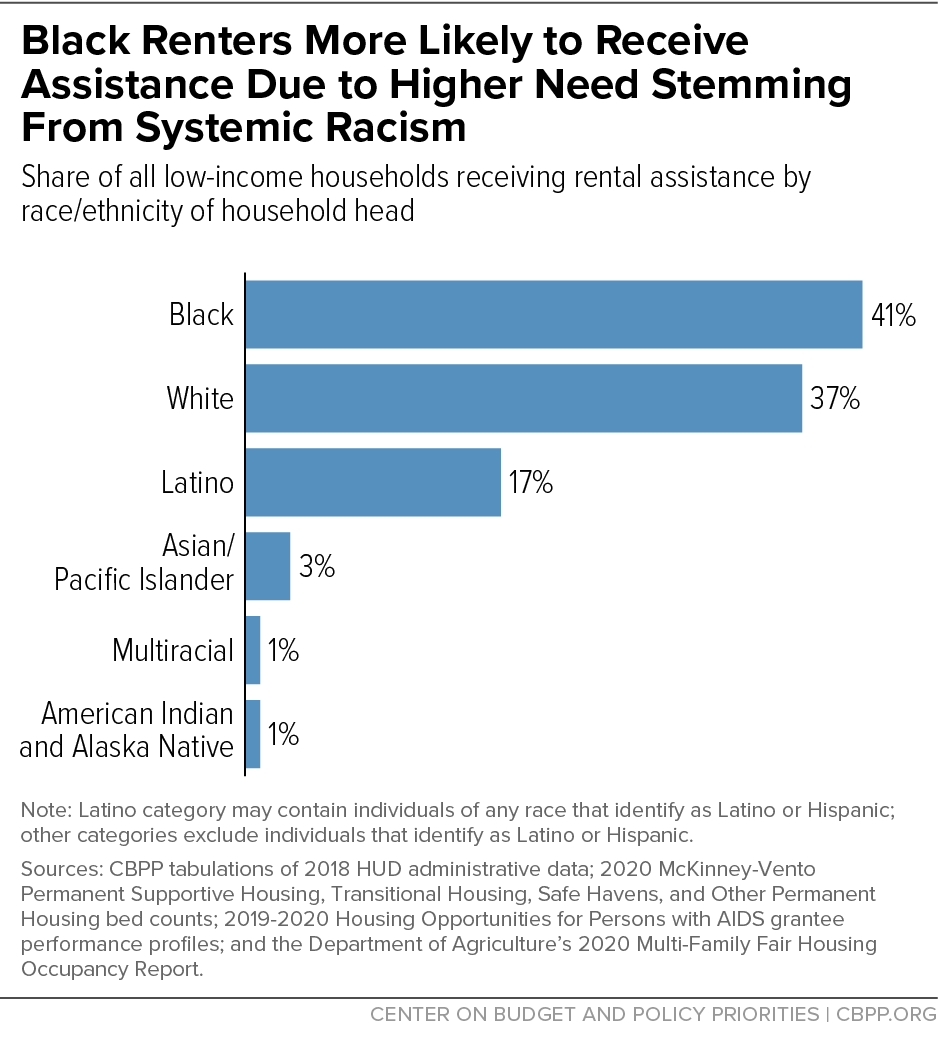

Rental assistance is poorly matched to need across all racial/ethnic groups. Limited funding leaves most renters without the assistance they need to afford safe and stable housing. Due to a long history of racist federal, state, and local housing policies, Black renters are disproportionately impacted by housing hardship. As a result, Black women, in particular, face a higher rate of eviction than other racial/ethnic groups, and Black people are also more likely to experience homelessness, making up 39 percent of all people experiencing homelessness but only 13 percent of the overall U.S. population. Due to this greater need, Black renters are therefore more likely to receive rental assistance compared to other racial/ethnic groups.

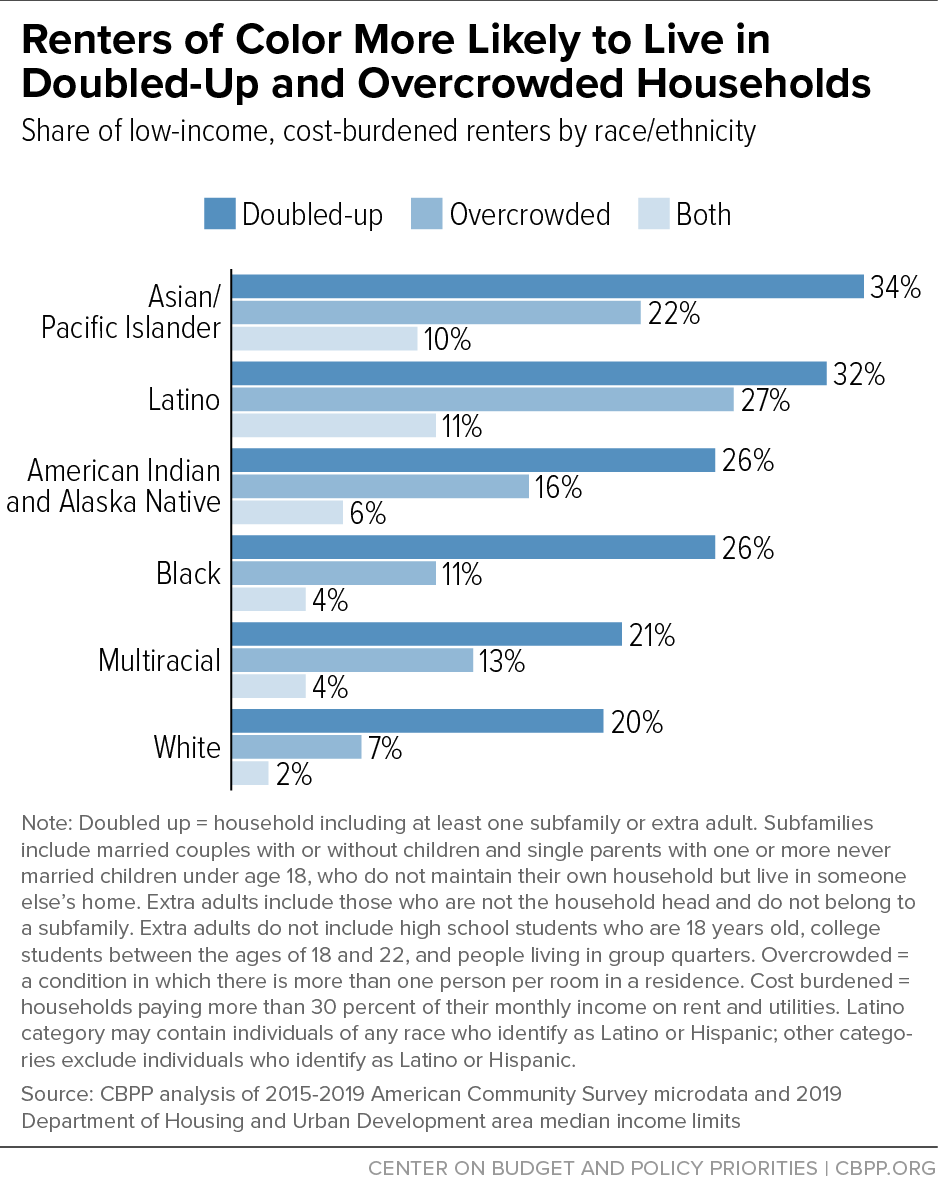

Asian and Pacific Islander, Latino, and Indigenous people have a higher likelihood of living with extended family in doubled-up and/or overcrowded households. These groups are underserved by rental assistance programs relative to their hardship. Over 1 in 3 low-income, cost-burdened (households paying more than 30 percent of their monthly income on rent and utilities) Asian and Pacific Islander renters live in doubled-up households, with 1 in 10 living in households that are both doubled up and overcrowded. Latino renters experience similarly high rates of doubling up and overcrowding. From 2009 to 2019, the number of Latino households with very low incomes either paying more than half their income for rent or living in severely substandard housing increased 22 percent compared to 10 percent for very low-income households overall. Research indicates that barriers, such as inadequate translation services and eligibility rules tied to immigration status, prevent Latino renters from accessing rental assistance.

American Indians and Alaska Natives have some of the worst housing needs due to a long history of oppression and systematic displacement. Yet they are similarly underserved by the rental assistance programs included in our analysis. AIAN households were significantly more likely to be overcrowded or doubled up compared to all U.S. households, a survey of tribal areas found. Rental assistance in tribal areas is funded through the Indian Housing Block Grant, but funding has failed to keep pace with inflation since its implementation in 1998, reducing the level of assistance it is able to provide. AIAN people living in urban areas are also disproportionately likely to experience overcrowding and homelessness. While living in urban areas provides access to mainstream rental assistance programs, most housing assistance is not targeted to AIAN households and service providers often lack cultural competency.

White renters make up a smaller share of assisted households compared to those in need of assistance. They also have higher incomes, on average, than other households, therefore, they are less likely to be among those newly admitted to rental assistance programs, which prioritize renters with extremely low incomes. Only 47 percent of low-income, cost-burdened white renters are extremely low-income, compared to 54 percent of renters of color.[2]

Black renters are more likely to receive rental assistance compared to other racial/ethnic groups due to higher need stemming from systemic racism and past and present discriminatory housing policies. In the early part of the 20th century, racist housing policies, such as redlining and restrictive covenants, restricted where Black people could live and helped create racially segregated neighborhoods. In the 1930s, the U.S. government began mandating separate public housing projects for white and Black tenants. Starting in the 1940s and continuing through the 1960s, federal policy explicitly prohibited Black people from accessing the same homeownership subsidies as white people, thereby worsening residential segregation and denying Black people homeownership’s wealth building opportunities. The Black-white homeownership gap, a 30 percentage point difference in 2019, and the racial discrimination Black renters continue to face illustrate the harmful legacy of these exclusionary policies.

Black renters in need of rental assistance also have lower incomes, on average, than other households, reflecting racial income disparities resulting from a long history of employment discrimination. This means Black renters are more likely to be among those newly admitted to rental assistance programs, which prioritize renters with extremely low incomes. Nearly 6 in 10 low-income cost-burdened Black renters have extremely low incomes, compared to less than half of white renters.[3]

End Notes

[1] CBPP analysis of Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) custom tabulations of the 2019 American Housing Survey.

[2] CBPP analysis of 2015-2019 American Community Survey microdata and 2019 HUD area median income limits.

[3] CBPP analysis of 2015-2019 American Community Survey microdata and 2019 HUD area median income limits.

More from the Authors