The 2018 omnibus spending bill enacted in March takes another positive step toward reversing funding cuts to the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) that policymakers made since the enactment of the Budget Control Act of 2011, and provides substantial new resources for HUD’s core housing assistance programs, including the largest increase in new housing vouchers since 2001. Overall, the bill increases HUD program funding by $4.7 billion, or nearly 10 percent over the 2017 funding level.[1] That’s almost a 30 percent increase above the proposal the Trump Administration submitted in May 2017, which would have dangerously underfunded housing programs and which Congress overwhelmingly rejected.[2] But even with these increased resources, HUD program funding remains below 2010 funding levels, adjusted for inflation. Due to funding limitations, it also remains the case that only about 1 in 4 households eligible for housing assistance will receive it.

The two-year bipartisan budget agreement that Congress reached in early February paved the way for increased housing funding by raising the Budget Control Act’s (BCA) caps on defense and non-defense discretionary program funding for fiscal years 2018 and 2019. Congress has raised the BCA funding caps in past years as well, recognizing that the austere funding caps, lowered by “sequestration” cuts, were too low to meet critical national needs. This agreement also should enable Congress to largely sustain these increased funding levels in 2019.[3]

In addition to providing significant funding increases and averting dramatic losses in housing assistance that would have resulted from the Trump Administration’s proposed funding levels, the bill did not include harmful rent increase proposals the Administration also included in its 2018 budget. These proposals would have raised rents on up to 4 million low-income households receiving rental assistance.[4]

Congress Maintains, Expands Critical Rental Assistance Programs

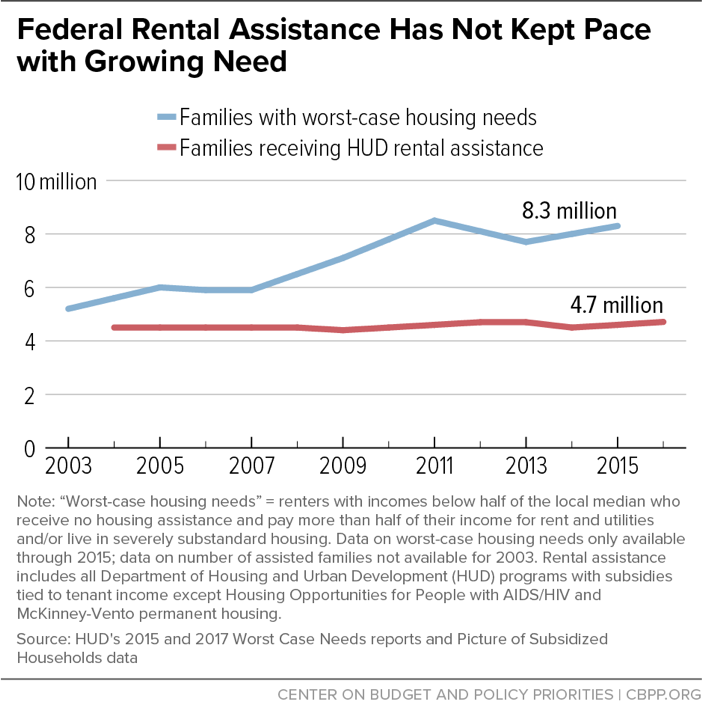

The 2018 appropriations bill provides enough funding to essentially maintain the current number of families receiving assistance through HUD’s core rental assistance programs, including Housing Choice Vouchers (HCV) and Project-Based Rental Assistance, and makes significant increased investments in the Public Housing program. It also expands vouchers for people with disabilities, veterans, and families with children in foster care by adding about 55,000 new targeted vouchers, which is the largest increase in new housing vouchers of any type since 2001. Even with the addition of these new vouchers, however, the number of families who need vouchers far exceeds their availability. (See Figure 1.)

The 2018 funding bill includes $22 billion for the HCV program, an increase of $1.7 billion (or 8.5 percent) above the 2017 level. This funding level is enough to continue essentially all housing vouchers now in use, while also providing 55,000 additional vouchers for targeted groups, particularly people with disabilities.

The cost of the HCV program rises with rental costs. For housing agencies to serve the same number of families from one year to the next, they must receive funding that accounts for rent increases in the communities they serve. The legislation includes $19.6 billion to renew housing vouchers that households currently use. Under the renewal formula, nearly all housing agencies that administer vouchers are eligible to receive funding equal to the 2017 costs of the vouchers that families used, adjusted for inflation and other factors.[5] After accounting for expected cost increases averaging 3.5 percent in 2018, HUD has determined that the appropriation will cover 99.8 percent of renewal costs this year, and has notified agencies of their 2018 renewal allocations.[6] The vast majority of housing agencies should be able to continue to assist at least the same number of households this year as in 2017.

Public housing agencies (PHAs) should make every effort to fully use the funds they receive to help as many families as possible. The number of families with “worst-case housing needs,” which HUD defines as unassisted renter households that either pay more than half of their income for rental costs or live in severely inadequate housing, is near a historic high of 8.3 million households. The unmet need for rental assistance across the country is significant and any available vouchers should be used to address this severe problem. PHAs should not only spend the funds they receive for 2018 but should also consider spending a portion of their reserves to ensure that subsidies keep pace with market costs as well as to serve more families.[7]

Housing agencies have other good reasons to use their funds effectively. For one, agencies’ eligibility for administrative funding is determined in part by the number of vouchers that families are using. (See below for more on administrative fees.) In addition, HUD rates agencies’ performance in part on how many households they serve, and takes these performance ratings into account in making consequential decisions — such as which agencies will receive funding for additional vouchers when Congress makes such funds available.[8]

The 2018 funding bill includes $1.76 billion to cover agencies’ administrative costs, which HUD estimates will provide them with about 76 percent of the funds for which they are eligible under the current HUD formula, and 2018 will be the eighth consecutive year of deep shortfalls in administrative funding.[9] PHAs use these funds to inspect units to ensure they meet federal health and safety standards, verify tenants’ income and eligibility, calculate families’ rent contributions, and for other operational functions. While it is difficult to specify precisely the impact of an estimated 24 percent shortfall in administrative funds, it is very likely that many agencies will continue to struggle to administer their programs effectively.[10]

The bill also provides a carveout of administrative funds that HUD can use to supplement formula fees for PHAs that have experienced extraordinary expenses, such as natural disasters, and for other priorities that HUD establishes.[11]

In the 2018 funding bill, Congress provided approximately $450 million in funding for new vouchers for three target groups — households headed by a person with a disability, homeless veterans, and families in which a child is at risk of being placed in foster care. The largest expansion in housing assistance is for households headed by a person with a disability; of the 55,000 new households that will obtain rental assistance through these new vouchers, 48,000 will be households headed by a person with disabilities. (A further discussion of the significance of the vouchers for people with disabilities is below.)

Continuing with its commitment to fund vouchers for homeless veterans, the funding legislation provides provided $45 million for an additional 5,000 such vouchers in 2018. Known as HUD-Veterans’ Affairs Supporting Housing (HUD-VASH), this program has succeeded in reducing veterans’ homelessness by nearly 50 percent since 2010.[12] With this new investment, Congress has funded nearly 100,000 new vouchers for homeless veterans since 2008.

The bill also includes funding for about 2,000 new Family Unification Program (FUP) vouchers, which help families that are at risk of having their children placed into foster care primarily because they lack adequate housing. FUP vouchers may also be used to help children in foster care to be reunified with their families, and to help youth who are exiting foster care, a large share of whom will experience homelessness without support.

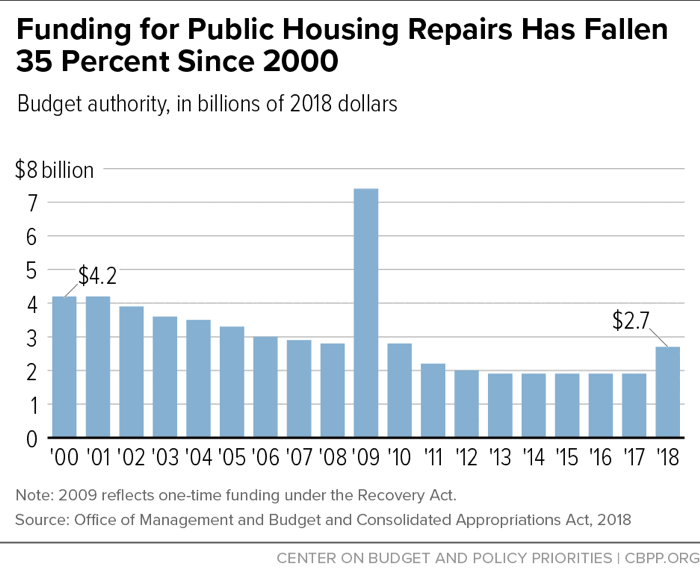

The Public Housing Capital Fund, which agencies use for updating and maintaining their housing stock, received its largest direct infusion of funds since the $4 billion the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act made available in 2009. The 2018 bill includes $2.75 billion for capital repairs, $809 million more than the 2017 funding level. Even with this significant increase, however, needs far outpace funding levels. A 2010 HUD study estimated that agencies faced a $26 billion backlog of capital repair needs, and that developments accrued new needs at a rate of $3.4 billion every year.[13] The 2018 funding level is likely inadequate to meet new needs accrued in the past year, and therefore the backlog will continue to grow, continuing the trend of severe underfunding since 2000. (See Figure 2.)

In addition to addressing the physical needs of public housing communities, the capital fund also includes funding for resident services programs. Congress provided $15 million for the Jobs-Plus demonstration, equal to the amount appropriated for 2017. Jobs-Plus provides grants to PHAs for employment services and earnings incentives for public housing residents. The capital repairs funding also includes $35 million for the Resident Opportunities and Supportive Services (ROSS) program, which provides grants to PHAs for program coordinators to link residents with job training and employment opportunities.

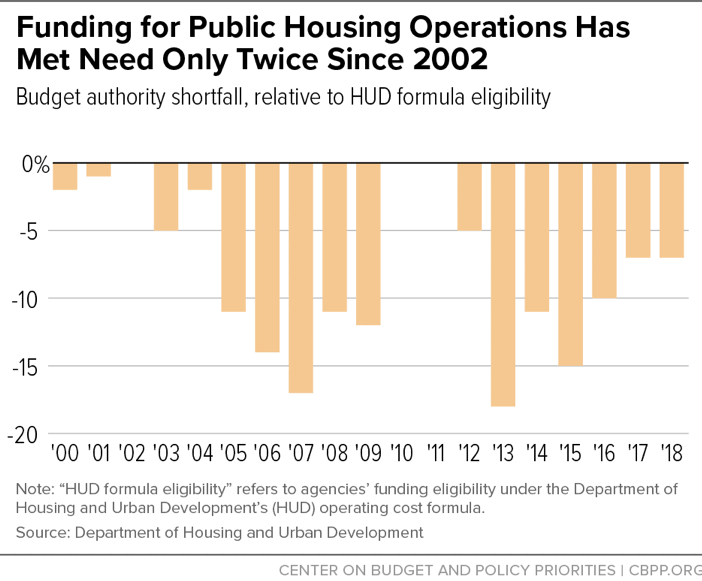

The Public Housing Operating Fund, which provides funds to PHAs for ongoing operational and utilities costs, also saw a modest increase of $150 million in the 2018 funding bill — but not enough to fully fund each PHA’s formula-based eligibility. As a result, HUD will prorate each PHA’s funding eligibility. Preliminary estimates indicate the proration will be roughly 93 percent — that is, the funding that agencies receive will be 7 percent below the amount for which they are eligible.[14] PHAs have received their full formula eligibility under HUD’s operating cost formula only twice since 2002. (See Figure 3.)

Recognizing the impacts of the long-term disinvestment in the public housing portfolio, HUD since 2010 has implemented two initiatives — the Choice Neighborhoods Initiative (CNI) and the Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) — that seek to leverage private capital to address communities that have fallen into disrepair.

The 2018 funding bill provides $150 million for CNI, which is a small increase ($12.5 million) from 2017. CNI provides grants to revitalize distressed publicly and privately owned assisted housing through a comprehensive neighborhood-based approach and helps leverage private funds to help maximize the housing investments.[15]

In addition to increased funding for public housing repairs, the 2018 bill also expands RAD, which allows public housing agencies (as well as owners of properties assisted under several HUD “legacy” programs) to address deferred maintenance needs by entering into long-term rental assistance contracts that can leverage private capital investment. Congress increased from 225,000 to 455,000 the number of public housing units eligible for conversion under RAD to a Section 8 project-based contract.

By providing these increased investments and RAD expansion, Congress has helped address the chronic underfunding of public housing, but it must do more to prevent further loss of units and unsafe living conditions.

Other Rental Assistance and Homelessness Programs Increased

Other HUD rental assistance programs also saw a significant boost over their 2017 funding levels. The $11.5 billion the bill provides for the Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance program is sufficient to fully renew assistance for the 1.2 million families currently served. Adequately funding this program, including rental increases consistent with owners’ contracts and market trends, is important to maintaining the level of affordable housing under contract with the federal government. In an era of significantly increasing housing need, maintaining housing stock targeted to the lowest-income families is critical.

Two other place-based rental assistance programs — Section 811, which serves non-elderly people with disabilities, and Section 202, which serves seniors — also saw increases in their funding levels. These investments will be discussed further below.

The Trump Administration proposed to cut homeless assistance grants by about $133 million. Communities rely on these grants to implement effective strategies that help people quickly exit homelessness move to stable housing, such as supportive housing. Instead of cutting the program, Congress increased it by about $130 million above the 2017 level, to $2.5 billion. This includes $80 million for an initiative to reduce youth homelessness, and $50 million for a new effort to provide short-term housing assistance and other services to survivors of domestic violence. This could mean the difference between life on the street and a place to live for about 20,000-25,000 people, the National Alliance to End Homelessness estimates.[16]

The 2018 funding bill includes numerous increased investments in rental assistance and capital funds for disabled and senior households. As explained above, the bill more than triples the number of “mainstream” vouchers that help non-elderly people with disabilities live independently in the communities of their choice. On top of the more than $120 million Congress allocated to renew and administer some 20,000 existing vouchers for non-elderly people with disabilities, the funding bill provides an additional $385 million to support 48,000 new vouchers for this population.[17]

Funding for the Section 811 program, which also serves non-elderly disabled households, increased by $82.6 million in the 2018 funding bill. These funds renew subsidies for existing units and provide capital advances and rental subsidies for an estimated 1,800 new affordable housing units.

The Section 202 program, which serves seniors, also receives an increase, with $105 million for new capital advances and rental assistance. This new funding could result in about 760 new units for seniors. With the exception of $10 million in 2017 funds that could be used for either new construction or preservation at HUD’s discretion, Congress has not provided new HUD funding for development of senior housing since 2011.[18]

In addition to these funding increases, the 2018 bill also expands eligibility to participate in the RAD program to 202 Project Rental Assistance Contract (PRAC) or “Housing for the Elderly” properties, which will help leverage additional capital for updating distressed properties.[19] The 202 PRAC program, administered by non-profit housing organizations, serves about 120,000 senior households. The 202 PRAC housing portfolio has been a focus of preservation efforts due to its increasing age ― with some of the 2,800 communities dating back to 1990 ― as well as the increasing need for affordable housing for the growing senior population.[20]

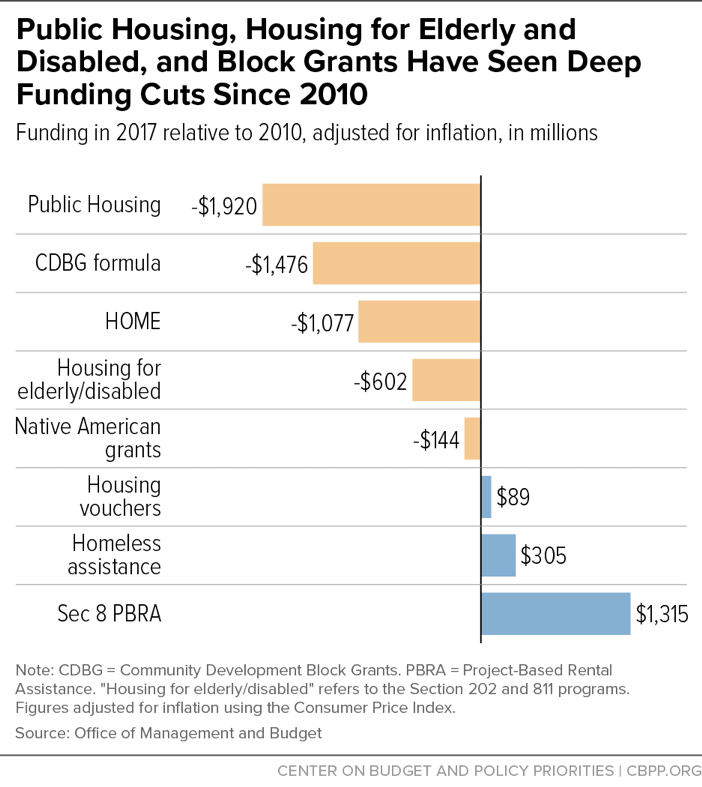

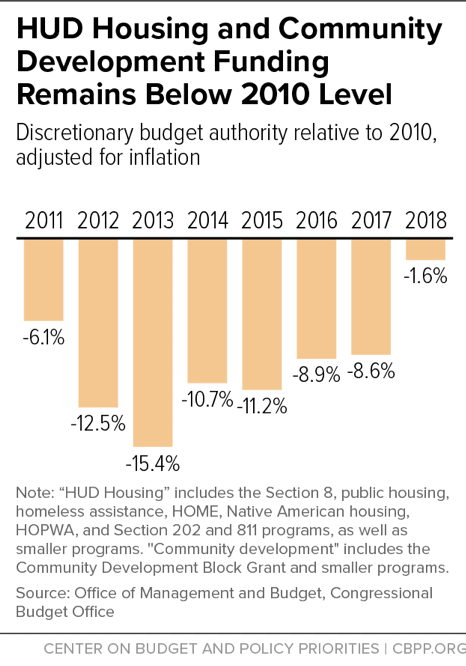

The predicate to the funding increases in the final 2018 omnibus funding bill was the agreement that Congress reached in early February 2018 to raise the austere 2018 and 2019 funding caps, established under the BCA, for both non-defense discretionary programs and defense programs.[21] The caps have forced significant funding reductions in housing assistance and community development programs since 2010. Public housing, housing for the elderly and people with disabilities, and the HUD block grants have seen the deepest cuts. (See Figure 4.)

The February agreement, which followed two similar agreements to raise the caps for fiscal years 2014-2015 and 2016-2017, increased the non-defense discretionary cap by $63 billion for 2018 and $68 billion for 2019. This agreement paved the way for the sizeable increases in HUD program funding that the 2018 funding bill provides and should also enable Congress to largely sustain these increased funding levels for 2019. Even with the funding increases in the 2018 bill, however, funding for HUD housing assistance and community development programs remains below the 2010 level, adjusted for inflation. (See Figure 5.)

Unless Congress acts again to modify the BCA, the current-law caps will force massive cuts in defense and non-defense programs again in fiscal year 2020 — an issue that will require policymakers’ attention next year.

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 |

|---|

| |

2017 |

Trump 2018 |

House 2018 |

Senate 2018 |

Enacted 2018 Bill |

|---|

| Housing Vouchers |

$20,292 |

$19,318 |

$20,487 |

$21,365 |

$22,015 |

| Renewals |

$18,355 |

$17,584 |

$18,710 |

$19,370 |

$19,600 |

| Admin fees |

$1,650 |

$1,550 |

$1,550 |

$1,725 |

$1,760 |

| New VASH, FUP, NED |

$60 |

|

$40 |

$80 |

$465 |

| Section 8 Project-Based |

$10,816 |

$10,751 |

$11,082 |

$11,507 |

$11,515 |

| Public Housing |

$6,342 |

$4,528 |

$6,250 |

$6,445 |

$7,300 |

| Homeless Assistance |

$2,383 |

$2,250 |

$2,383 |

$2,456 |

$2,513 |

| Section 202 Housing for Elderly |

$502 |

$510 |

$573 |

$573 |

$678 |

| Section 811 Housing for People with Disabilities |

$146 |

$121 |

$147 |

$147 |

$230 |

| Housing Opportunities for People with HIV/AIDS |

$356 |

$330 |

$356 |

$330 |

$375 |

| HOME Block Grants |

$950 |

$0 |

$850 |

$950 |

$1,362 |

| Native American Housing Block Grants |

$654 |

$600 |

$654 |

$655 |

$657 |

| Community Development Block Grants |

$3,000 |

$0 |

$2,900 |

$3,000 |

$3,300 |

| HUD Program Total (gross) |

$48,056 |

$40,722 |

$48,034 |

$49,942 |

$52,749 |