Using Asset Verification Systems to Streamline Medicaid Determinations

State Medicaid agencies operate electronic asset verification systems (AVSs) that collect information directly from financial institutions to determine whether certain seniors and people with disabilities who are applying for or receiving Medicaid have assets below eligibility caps. This paper explores the background of the AVS requirement, instituted by a 2008 federal law; the vendors that administer the systems; and the typical AVS process. It discusses AVSs’ current limitations and highlights best practices for advocates to promote and state agencies to implement to improve the AVS process and streamline eligibility determinations. Finally, it recommends federal action to help AVS states streamline processing.

Before AVSs, seniors and people with disabilities who were applying for or renewing Medicaid had to submit documents such as bank statements to prove their assets. AVSs reduce paper documentation requests by obtaining electronic verification, which streamlines and expedites application processing, eases burdens on applicants and eligibility workers, and reduces the number of eligible individuals who are denied or lose coverage for failing to comply with requests for documents. Though AVSs have limitations, states should explore policies that improve their implementation and ultimately ensure that eligible individuals can successfully enroll and retain their coverage.

The end of the COVID-19 public health emergency presents an opportunity for states to implement policies that make the unwinding process easier and more efficient for both state agencies and beneficiaries.The end of the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) presents an opportunity for states to implement policies that make the unwinding process easier and more efficient for both state agencies and beneficiaries. States will have to conduct renewals on a large number of cases, including those that already are subject to asset tests and those where people are transitioning into eligibility groups that require an asset test (such as people who turned 65 during the PHE). Strengthening AVS policies and procedures can streamline these processes.

Background

Most seniors and people with disabilities — often referred to as “non-MAGI” to distinguish them from Medicaid populations whose eligibility is based on modified adjusted gross income — are subject to a limit on the amount of resources they can have in order to qualify for Medicaid coverage. States have flexibility in setting the asset limit for their non-MAGI programs, though most states still apply an asset test.[1]

Prior to the implementation of AVSs, state agencies had to manually verify assets at application and renewal. Individuals reported the value of any assets they had, including bank accounts, to the state agency at application and often had to obtain and submit copies of their bank statements as verification. This manual process delayed eligibility determinations and often led to application denials if individuals couldn’t secure and submit the required documentation. The process was particularly burdensome for individuals seeking long-term services and supports (LTSS) who had to provide bank statements for the 60-month “lookback period” prior to application to verify that they hadn’t transferred any assets to bring their assets below the limit.

In 2008 Congress began requiring states to implement asset verification programs. Such systems must obtain authorization from applicants and collect records from financial institutions that the state agency can use in determining and redetermining Medicaid eligibility for seniors and people with disabilities.[2] The statute allows states to contract with public or private entities in order to implement their programs.

Few states met the initial deadline to implement an AVS by the end of fiscal year 2013. By 2016, most states had submitted state plan amendments (SPAs) and were approved, but only four states had actually implemented their AVS.[3] Congress then set a new deadline of January 2021 for states to comply or face a reduction in their federal matching.[4] The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) also improved its oversight of state implementation of AVSs by increasing its communication with noncompliant states, requiring more structured and detailed timelines and implementation deliverables to be included in SPAs, and by more closely monitoring and tracking state progress towards implementation.[5] All states have now implemented an AVS or are in the process of doing so.

AVS Vendors

States have contracted with vendors to implement their AVS.[6] These are the main vendors involved:

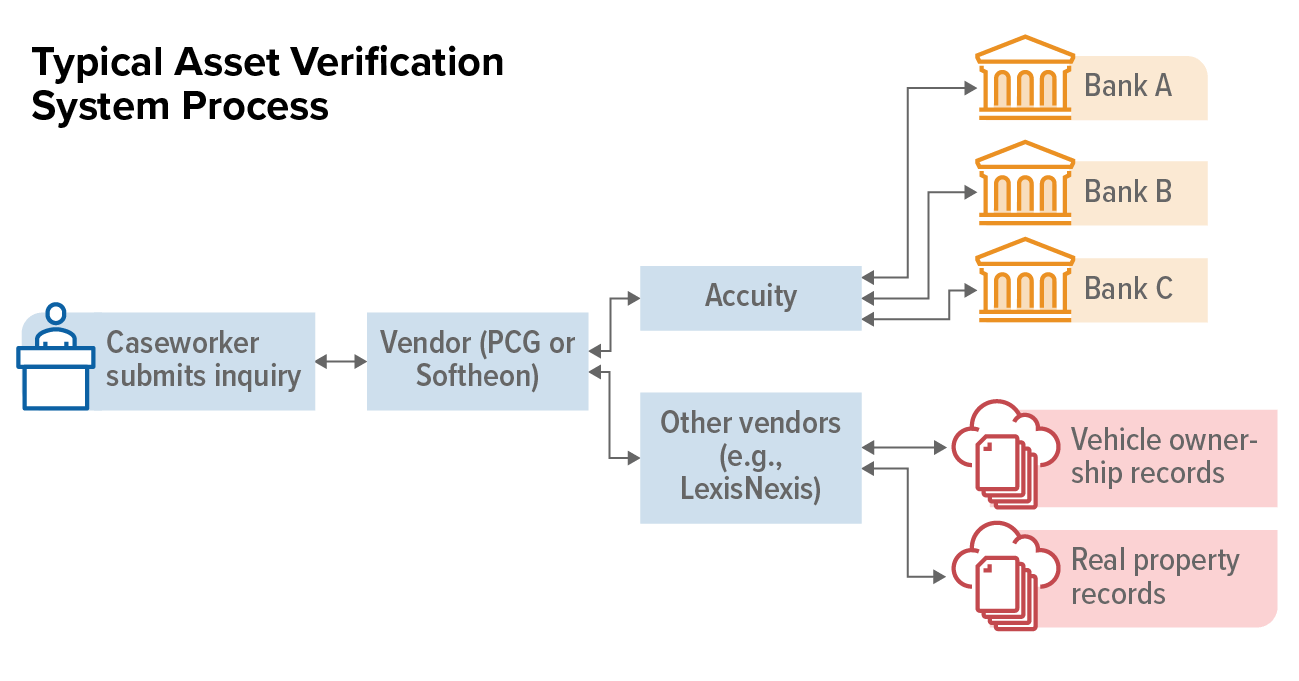

- Accuity, the official registrar for financial institution routing number systems and partners with banks across the United States,[7] has established a system utilizing this network to obtain individual bank account balances in response to inquiries from Medicaid agencies.

- Vendors such as Public Consulting Group (PCG) and Softheon help states interact with Accuity. They establish portals or ways that eligibility systems can pass data requests on to Accuity and then process the responses. They may also provide information on other countable assets such as real estate and vehicles and provide analytics such as assessments of the risk that an individual has assets that exceed Medicaid eligibility thresholds.

- Some states use data from LexisNexis and TransUnion, often through their AVS vendor, for asset information in addition to the bank account data provided by Accuity. LexisNexis and TransUnion provide data from public records about property ownership, registered vehicles, and other physical assets that may affect an individual’s eligibility for Medicaid.

State Implementation of AVS

Though states vary in how they implement their AVS, the process generally includes the following steps:

- Individual applies for Medicaid. Someone who applies for Medicaid and may be eligible for a non-MAGI category with an asset test must answer questions about their bank accounts and other assets. They typically must list the name of the financial institution and their current balance on the application and sign the application attesting that the information they have given is accurate. By signing and submitting the application, they give the Medicaid agency permission to make inquiries to verify the information they provided.

- Caseworker submits inquiry. When a caseworker reviews an application, they attempt to verify eligibility factors against electronic data sources. (See Figure 1 for this and other steps in the process.) To verify assets, they submit the individual’s information through the AVS. In some states, the AVS is integrated into the eligibility system, which automatically sends the inquiry along with other inquiries to other data sources, such as the Social Security Administration. In other states, the AVS is in a stand-alone portal that the caseworker must log into and manually submit the individual’s information.[8]

- The AVS searches for records at financial institutions. The system sends out inquiries to national banks and local financial institutions based on the individual’s address. The system may also search for specific banks outside its normal criteria if the caseworker specified an institution where the applicant disclosed assets. Some larger banks have automated interfaces with the AVS and provide responses in virtually real time while other banks respond to Accuity manually, sometimes faxing information to Accuity, which is then entered into the AVS.

- The AVS returns results. AVS results contain the name and address of the financial institution and the balance of the account on the first day of the month. For LTSS applicants, the AVS can provide balances for the 60-month lookback period prior to application. Results can take from minutes to days to be returned, depending on how responsive the bank is. Most agencies leave the inquiry open for a set period, such as ten or 14 days, to wait for all results to come in.

- Eligibility worker takes action based on AVS results. If the information returned through the AVS is consistent with the information on the person’s application and is under the asset eligibility threshold, the caseworker moves forward with processing the case. If the information is inconsistent or suggests ineligibility, the caseworker follows up with the applicant and requests additional verification.

An AVS can also be used during the renewal process to verify assets. Some states send an inquiry through an AVS for all non-MAGI cases due for renewal in a month through a batch process (see box, “Real-Time Access vs. Batch Processes”). They then use this information to attempt an automated ex parte renewal.[9] In states that don’t complete a batch process for cases due for renewal, the caseworker reviewing the case must submit a manual inquiry through an AVS for each individual at renewal.

Limitations of AVS

While AVSs help states streamlineine non-MAGI determinations, they are a relatively new technology with limitations. Among the challenges states face are that:

- Not all financial institutions participate. Accuity can’t get results from all institutions, presenting challenges in rural settings where populations may rely more heavily on local credit unions than large banks.

- Not all AVS results are available in real time. Banks may take up to two weeks to respond to AVS inquiries. While larger financial institutions typically have the infrastructure to provide information electronically in minutes or hours, smaller institutions may need to manually process requests and return the results via fax or mail. To ensure applications are processed timely, an eligibility worker may request paper documentation from the applicant while waiting for the AVS results, reducing the streamlining benefits of the system.

Real-Time Access vs. Batch Processes

Eligibility workers and state systems access data sources either in real time or through a batch process. Real-time access allows an eligibility worker to enter individual case information into a portal and immediately receive a response. In a batch process, information for a large number of clients is provided to a data source which then provides responses for all of the clients in that request, usually overnight. While eligibility workers often access sources in real time, batch processes are used for ex parte Medicaid renewals to gather information for large numbers of monthly renewals.

- Electronic data may be lacking for some countable assets. While Accuity provides information on bank account balances, caseworkers must also verify other countable assets for non-MAGI applicants. States may obtain additional information on property and vehicles through other vendors included in their AVS, but electronic data aren’t available for other countable resources such as life insurance and stocks.

- Costs can be high. Most AVSs charge per inquiry and can be expensive. The cost is greater if the state agency chooses more comprehensive features that the vendor offers, such as data for other types of assets in addition to financial institutions. There is also a cost involved in integrating an AVS into a state’s eligibility system. Though states must implement an AVS, the high cost of particular features can prevent agencies from using it to its fullest potential.

Best Practices for AVS Implementation

The efficient use of AVSs in the application and renewal process can greatly benefit both state agencies and applicants. An AVS can eliminate the need for applicants to go through the burdensome process of obtaining and submitting paperwork for their application to be processed, which particularly benefits those applying for LTSS who would otherwise have to obtain five years of bank statements. An AVS can also decrease the amount of agency time spent in processing the application and making an eligibility determination.

Medicaid agencies make a number of policy and operational decisions that influence how much AVSs streamline non-MAGI determinations. Advocates working to improve the application and renewal process can review current state policy and practice and identify areas for improvement. Below are best practices for asset verification to reduce requests for documentation at application and as part of the ex parte renewal process to accelerate processing, reduce denials for failure to return paperwork, and save workers time.[10]

AVS at Application

AVSs provide an electronic resource to verify asset eligibility, similar to the electronic data sources available to verify income eligibility. As with income verification, agencies should use the information in an AVS to verify the individual’s statement on an application and only request additional information if the two are not reasonably compatible.

Reasonable compatibility is commonly used for income verification but applies to asset verification as well. Under this policy, the client statement (on the application form) and data source are considered “reasonably compatible” if they are both below the eligibility threshold. They are reasonably compatible even if there is a significant difference between the attestation and data source as long as that difference doesn’t affect eligibility. For assets, if the information the client provides and the information available through the AVS are both below the asset threshold, the client is eligible and the agency should not request further information from the client.

Agencies also can’t deny applicants solely based on information provided by an AVS. If there are inconsistencies between self-attested and electronic data, and the electronic data suggest that the applicant is ineligible, caseworkers must ask for more information from the applicant before denying or terminating their coverage.[11] (See box for how this works in Wisconsin, for example.)

While reasonable compatibility is a straightforward policy, its application to different scenarios can be complicated. Agencies should provide clear policy around the use of reasonable compatibility at application and instruct caseworkers when to request and not to request documentation from the applicant. (See Table 1). In addition, policies should direct caseworkers not to request information from the client while the AVS results are pending. Rather, the caseworker should wait a reasonable time until the majority of the AVS results have come back and only request documentation from the client if there is contradictory information in those results.

Reasonable Compatibility in Wisconsin

Wisconsin applies a reasonable compatibility test to assets that minimizes requests for verification. When both the self-attested information and AVS results are below the asset limit, the reasonable compatibility standard is met, and caseworkers are prohibited from requesting additional verification from the individual. If the self-attested information is below the asset limit but the AVS results are above it, caseworkers must request additional information from the applicant but may not deny or terminate an individual’s application or case based solely on the information provided by the AVS.

| TABLE 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reasonable Compatibility at Application The scenarios below are for a program with a $2,000 asset limit. |

||||

| Scenario | Client statement | AVS result | Reasonably compatible? | Outcome |

| Client statement and AVS match, assets below threshold | $1,000 at Bank A | $1,000 at Bank A | Yes | Eligible — no further information needed |

| Client statement and AVS differ, but both are below threshold | $1,000 at Bank A | $1,800 at Bank A | Yes | Eligible — no further information needed |

| No information found by AVS | $1,000 at Bank A | No bank account information found | Yes | Eligible — no further information needed |

| AVS shows additional asset, total below threshold | $1,000 at Bank A | $1,100 at Bank A, $200 at Bank B ($1,300 total balance) | Yes | Eligible — no further information needed |

| AVS shows assets above eligibility threshold | $1,000 at Bank A | $2,100 at Bank A | No | Request additional verification |

Agencies may also use post-enrollment verification for assets and approve an application based on the applicant’s attestation of assets below the eligibility threshold. After enrollment, the agency verifies the information through an AVS. If the AVS results are not reasonably compatible, the agency can request verification from the client and terminate coverage if the client doesn’t provide the necessary documents in a timely manner. Approving Medicaid at the time of application can ensure that seniors and people with disabilities can quickly access needed medical care.

Agencies can also use an AVS to improve their real-time eligibility (RTE) rates. RTE refers to applications that are processed immediately (or within 24 hours), primarily relying on automated data checks and rules within the eligibility system. An AVS allows states to electronically verify assets at application and approve cases in real time. To account for AVS results that may take days to return, agencies may combine RTE with post-enrollment verification. If AVS results returned after approval are inconsistent with the client statement, agencies can request additional information.

AVS at Renewal

Agencies must attempt to renew all Medicaid cases using information in the enrollee’s case or in electronic data sources before requesting information from the enrollee, a process known as an ex parte renewal. While most agencies use the ex parte process to renew the coverage of MAGI enrollees, they often exclude non-MAGI cases due to challenges in electronically verifying assets. The implementation of AVS allows states to increase their ex parte rates for non-MAGI groups. Agencies can automatically submit an inquiry to an AVS for all cases due for renewal via a batch process about 15 days before the system attempts to conduct the ex parte renewal. The AVS results will then be available when the system evaluates the individual for ongoing eligibility and can be used to verify assets and automatically renew coverage. Reasonable compatibility applies at renewal as well. (See Table 2.)

| TABLE 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reasonable Compatibility at Renewal The renewal scenarios below are for a program with a $2,000 asset limit. |

|||

| Scenario | Case information | AVS result | Outcome |

| Case information and AVS match, assets below threshold | $1,000 at Bank A | $1,000 at Bank A | Eligible — no further information needed |

| Case information and AVS differ, but both are below threshold | $1,000 at Bank A | $1,800 at Bank A | Eligible — no further information needed |

| No information found by AVS | $1,000 at Bank A | No bank account information | Eligible — no further information needed |

| AVS shows additional asset, total below threshold | $1,000 at Bank A | $1,100 at Bank A, $200 at Bank B ($1300 total) | Eligible — no further information needed |

| AVS shows assets above eligibility threshold | $1,000 at Bank A | $2,100 at Bank A | Request additional verification |

If a case is not successfully renewed through the ex parte process, the agency sends a renewal form to the enrollee that they must sign and return. The enrollee provides updated information about their income and assets, and an eligibility worker verifies these statements through electronic data sources, including an AVS. For these enrollees, agencies should use the AVS like they do at application and only request documents from the enrollee if the client’s statement and AVS results aren’t reasonably compatible.

Federal Action

In addition to key steps states can take to streamline the processing of non-MAGI cases, the federal government can support these efforts. CMS should provide comprehensive guidance to states on AVS implementation including details on how reasonable compatibility applies to assets. Specifically, CMS should direct states to complete an ex parte renewal when no information is found in the AVS, reversing prior guidance requiring a signed renewal form from the enrollee attesting to no assets when no results are found in the AVS.

CMS should also explore ways to reduce costs of AVS contracts and increase financial support to states to ensure they can access all relevant information for determinations. Finally, CMS should explore ways to increase the participation of financial institutions in AVSs so the results are timely, complete, and reliable.

End Notes

[1] For more information on state income and asset limits for the non-MAGI population, see MaryBeth Musumeci, Priya Chidambaram, and Molly O'Malley Watts, “Medicaid Financial Eligibility for Seniors and People with Disabilities: Findings from a 50-State Survey,” Kaiser Family Foundation, June 14, 2019, https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-financial-eligibility-for-seniors-and-people-with-disabilities-findings-from-a-50-state-survey-appendix-tables/.

[2] Section 1940 of the Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. 1396w.

[3] Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “State Compliance with Electronic Asset Verification Requirements”, October 2020, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/State-Compliance-with-Electronic-Asset-Verification-Requirements.pdf.

[4] Section 1940(k) of the Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C. 1396w.

[5] Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “State Compliance with Electronic Asset Verification Requirements”, October 2020, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/State-Compliance-with-Electronic-Asset-Verification-Requirements.pdf.

[6] Some states have also partnered with vendors through a consortium, such as the New England States Consortium Systems Organization (NESCSO). This allows for multiple states to work with the same vendor in a centralized manner, expediting the implementation process and reducing costs that would be incurred through an individual state contract. https://eohhs.ri.gov/sites/g/files/xkgbur226/files/Portals/0/Uploads/Documents/1115Waiver/AVSNoticetoPublic3.5.18.pdf.

[7] Accuity, “Accuity Asset Verification Services”, https://accuity.com/perspective/accuity-asset-verification-services/.

[8] Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, “State Compliance with Electronic Asset Verification Requirements”, October 2020, https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/State-Compliance-with-Electronic-Asset-Verification-Requirements.pdf.

[9] Jennifer Wagner, “Streamlining Medicaid Renewals Through the Ex Parte Process,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 4, 2021, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/streamlining-medicaid-renewals-through-the-ex-parte-process.

[10] For an example of a state’s detailed AVS implementation policy, see Oregon Department of Human Services, “Asset Verification Service (AVS)”, January 1, 2019, http://www.dhs.state.or.us/spd/tools/AVS/AVS%20Manual%202.14.19.pdf.

[11] 42 CFR §435.952(d).

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work: