Montana’s Medicaid expansion has been extremely successful, extending coverage and access to care to nearly 95,000 low-income adults since January 2016 and connecting many with workforce development services.[1] But Montana policymakers are reportedly considering proposals to take Medicaid coverage away from people who don’t meet a work requirement, charge low-income adults high premiums, and make eligibility contingent on completing extra paperwork related to their job readiness and health status.[2]Most Montana Medicaid beneficiaries either work or might qualify for exemptions from work requirements, but they would still be at significant risk of losing coverage from these proposals, due to the additional paperwork and red tape, not being able to meet the hourly requirement each month, and the overall confusion such requirements cause. Any proposal that takes coverage away from people not meeting work requirements would have similar harmful effects, and could undermine the success of Montana’s nationally recognized workforce promotion program.

The sponsor of the Montana legislation, Rep. Ed Buttrey, recently stated, “I’m not trying to do something that’s going to cause enrollment numbers to drastically change.”[3] But in Arkansas, the only state to have implemented a Medicaid work requirement to date, more than 1 in 5 of those subject to the new policy lost coverage in just the first seven months, amounting to more than 18,000 people. The share losing coverage under a Montana work requirement would likely be similar or even greater.

- Many workers and people eligible for an exemption would likely lose coverage. As noted, most Medicaid enrollees in Montana are working or appear to qualify for exemptions from work requirements. But that does not mean they would be safe from losing coverage. Rather, people with disabilities, caregivers, older people, and American Indians are at particular risk of losing coverage because they would likely face special challenges complying with the new paperwork and reporting requirements. Perversely, low-wage workers are also particularly at risk, since they often have fluctuating work hours and spells between jobs that make it impossible to meet monthly hours requirements.

- Raising premiums would create financial hardship and could cause further coverage loss. Extensive research shows that premiums significantly reduce low-income people’s participation in health coverage programs. The Buttrey proposal would reportedly raise Medicaid premiums as high as 5 percent of family income, the highest in the country for beneficiaries with incomes below the poverty line and more than twice what near-poor adults pay for Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplace coverage. Montana’s premiums are already unaffordable for some Medicaid beneficiaries; any increase would impose a serious financial burden on more individuals and families.

- Increasing Medicaid’s complexity would divert resources from helping people find jobs to paperwork and bureaucracy. States that are implementing or have considered similar Medicaid changes estimate the implementation costs at tens of millions of dollars per year, with some states estimating tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars in additional start-up costs.

- Coverage losses would increase hospitals’ uncompensated care costs. Among states adopting the Medicaid expansion, hospitals’ uncompensated care costs have fallen at roughly the same rate as their uninsured rates have fallen. The Buttrey proposal could reverse this progress in Montana.

That’s why a coalition of Montana health providers and business leaders are urging legislators “to continue Medicaid expansion without imposing unreasonable barriers to coverage.” They wrote, “Without health insurance, Montanans are more likely to seek the wrong care, at the wrong time and at the wrong place — with poorer outcomes and higher costs. . . . Coverage is the keystone to improving the health of our residents, increasing the efficiency of our health care system and decreasing costs for consumers, businesses and the state.”[4]

Montana’s Medicaid expansion covers about 95,000 low-income adults, or about 9 percent of the state’s population. More than 90,600 adults have received preventive services through the program since January 2016, including 7,600 women receiving breast cancer screenings with 107 receiving a breast cancer diagnosis. More than 30,000 adults have received mental health services; 900 have received a diabetes diagnosis and treatment.[5]

Along with access to health care services, Montana’s Medicaid expansion connects enrollees with workforce training. When Montana policymakers expanded Medicaid to more low-income adults under the Affordable Care Act in 2015, they authorized the Department of Labor & Industry to administer a workforce promotion program — Montana’s Health and Economic Livelihood Partnership Link (HELP-Link) — for the newly eligible population. HELP-Link targets outreach and services to the minority of Medicaid enrollees who don’t have disabilities or similarly severe barriers to work but who aren’t working, often due to challenges such as limited skills and lack of access to transportation, child care, or other needed work supports.

Since the program’s start, 25,000 expansion beneficiaries have enrolled in workforce training through the Department of Labor and Industry. Of those, 62 percent were employed in the quarter after completing training, and 70 percent were employed within a year. Fifty-eight percent of participants report wage increases in the year after participating, with a median increase of more than $8,000 in annual wages. While the state hasn’t analyzed how many people would have found employment without the training, the above figures show the program’s promise.[6]

HELP-Link is a national model for supporting Medicaid beneficiaries in the workforce. But its success could be impeded by a waiver that takes coverage away from people who don’t meet a work requirement and raises premiums on low-income beneficiaries. If Montana wants to help low-income adults find jobs and climb a career ladder, further investment in this promising program would do much more to achieve this goal than taking coverage away from Medicaid beneficiaries, which would likely make it harder for some to work, as discussed below.

Arkansas, the first state to take Medicaid coverage away from people who don’t meet a work requirement, has terminated coverage for more than 18,000 Medicaid beneficiaries — or about 23 percent of those subject to the requirement — since the policy took effect in June 2018.[7] Moreover, most beneficiaries in Arkansas were exempt from reporting their work activities or proving that they are exempt from the requirement: the state used administrative data to exempt parents, those who were working when they enrolled or last renewed their coverage and those who were enrolled in SNAP, among other groups. If Montana imposed work requirements without automating exemptions, coverage losses could be far steeper than that 23 percent figure suggests. In Arkansas, about 75 percent of those who had to report hours monthly lost coverage in the first seven months.[8]

These coverage losses would cause significant harm. Indeed, two groups for whom coverage losses or interruptions are especially harmful — people with serious chronic health conditions, including mental illness, and people with substance use disorders — make up a large fraction of those likely to lose coverage due to work requirements. An Ohio study found that nearly one-third of adults enrolled through the ACA Medicaid expansion have a substance use disorder, while 27 percent have been diagnosed with at least one serious physical health condition, such as diabetes or heart disease, just since enrolling in Medicaid.[9] A Michigan study found that among non-working Medicaid expansion enrollees, 72 percent have a serious chronic physical health condition, while 43 percent have a mental health condition, often depression.[10] For people with these conditions, even temporarily losing access to medications or other treatment could be harmful or sometimes catastrophic.

This is one reason why major physician organizations — including the American Medical Association, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association, and American Psychiatric Association — oppose Medicaid work requirements.[11]

Any policy to take coverage away from people who don’t meet a work requirement would almost certainly cause many low-income adults to lose health coverage, as noted above. In 2016, two-thirds of Montana’s non-elderly adult Medicaid beneficiaries who were not eligible for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) were working full or part time, and of those who were not working, 37 percent reported that they were ill or disabled, 33 percent had caregiving responsibilities, and 18 percent were in school.[12] One might conclude that most enrollees would be safe from losing coverage under a work requirement. But in reality, working people and vulnerable beneficiaries would face particular challenges complying with new reporting requirements, and many would likely lose coverage.

In Arkansas, it’s clear that people who are working or eligible for an exemption are losing coverage. Only about 4 percent of those subject to the work requirement in 2018 were neither working nor qualified for exemptions, studies estimate, yet each month, 13 to 29 percent of those subject to the requirement failed to report sufficient hours, most of them not reporting any hours.[13] These data suggest that many people who are working or eligible for an exemption are losing coverage. Likewise, focus groups with Arkansans who lost coverage due to the work requirement found that many didn’t know they were subject to the requirement or understand how to comply, and others have struggled to navigate the application and verification process.[14] News accounts have also described examples of eligible people losing coverage, including a working beneficiary who lost coverage because he didn’t report hours on time, then lost his job because he couldn’t obtain the medications needed to manage his chronic condition.[15]

Consistent with Arkansas’ experience, Kaiser Family Foundation researchers estimate (based on evidence from past eligibility restrictions in Medicaid) that about 80 percent of those who would lose coverage under a nationwide Medicaid work requirement would be working people and people eligible for exemptions who failed to complete the required paperwork.[16]

Groups at particular risk of losing coverage under a Montana work requirement include:

-

People with disabilities, caregivers, and students. Even if Montana exempted people with disabilities, those with full-time caregiving responsibilities, and those attending school, some people with serious barriers to work would not meet the criteria for exemptions or would struggle to overcome the bureaucratic hurdles to document that they qualify. That’s because rules for reporting and claiming exemptions increase paperwork and red tape, which cause eligible people to lose coverage. Efforts to inform beneficiaries of the complex compliance requirements and the processes for reporting and claiming exemptions would inevitably have gaps, leaving people without the information and help they need to comply. For example, even if the proposal included an exemption for people deemed “medically frail,” many people with disabilities likely wouldn’t qualify for an exemption or wouldn’t be able to prove that they did.

Likewise, people coping with serious mental illness or physical impairments might have trouble obtaining physician testimony, medical records, or other documents required to qualify for exemptions. Mental illness often affects the cognitive functions needed to navigate complex bureaucratic systems, making it hard for someone to qualify and often leading them to give up and drop out of the process.[17]

Studies of state Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF, or cash assistance) programs and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly food stamps) have found that people with disabilities, serious illnesses, and substance use disorders are disproportionately likely to lose benefits, even when they should be exempt. For example, an Ohio evaluation found that 32 percent of individuals subject to the SNAP work requirement reported a physical or behavioral health limitation that likely should have exempted them from the requirement.[18]

-

Workers. For people with low-wage jobs, such as food services, construction, or retail, work hours often fluctuate from month to month, leaving them short of the required minimum in some months even as they exceed it in others. Low-wage jobs are also unstable, with frequent job losses that leave people without work in some months. Also, some enrollees who meet the work requirement might still lose coverage because they got tripped up by red tape and paperwork.

Nationally, among adults age 19-64 not receiving SSI or SSDI and with incomes that would qualify them for Medicaid, most worked at least some of the year. But among those who were working, 46 percent worked fewer than 80 hours in at least one month, putting them at risk of losing their health coverage under an 80-hour-per-month work requirement. Even among those who worked at least 1,000 hours over the course of the year — or about 80 hours per month, on average — 25 percent would have failed to meet the proposed work requirement in at least one month.[19]

Moreover, as noted below, Medicaid coverage itself supports work, while losing health coverage worsens health and can make it harder to find or keep a job. That’s especially true for people with serious health conditions, whose health can deteriorate without access to medication and other treatment — making it even harder to work.

- American Indians. American Indians are disproportionately likely to be unemployed, in part because they are likelier to live in areas with limited job opportunities. The American Indian and Alaska Native unemployment rate in Montana averaged 15.1 percent from 2013 through 2017, almost 260 percent higher than the 4.2 percent rate for all other adults in Montana.[20] Lack of jobs would make it difficult for American Indians to meet a Medicaid work requirement.

Extensive research shows that premiums significantly reduce low-income people’s participation in health coverage programs: the lower a person’s income, the less likely they are to enroll and the more likely they are to drop coverage due to premium obligations.[21] And low-income people who lose coverage most often end up uninsured and unable to obtain needed health care services.

Montana’s premiums are already among the highest in the nation at 2 percent of family income for those above 50 percent of the federal poverty line (or $10,665 annual income for a family of three in 2019). Those above the poverty line who don’t pay their premiums for 90 days are disenrolled from coverage. Those with incomes between 50 and 100 percent of the poverty line who don’t pay premiums are not disenrolled, but the amount owed is considered collectible debt, which could substantially affect their financial well-being. These premiums are already unaffordable for many enrolled Montanans, the state’s recent waiver evaluation suggests.[22]

The proposed Medicaid changes would reportedly raise premiums to as high as 5 percent of family income, the highest in the country for beneficiaries with incomes below the poverty line and more than twice what near-poor adults pay for marketplace coverage. This would impose a serious financial burden on many beneficiaries, causing more people above the poverty line to lose coverage. The coverage losses would grow further if the state began terminating coverage for those below the poverty line who cannot pay premiums.

Moreover, the proposal would penalize those who stay on Medicaid by raising premiums by 0.5 percent of family income per year (up to the new 5 percent limit). This would penalize the many working beneficiaries who don’t have an affordable alternative to Medicaid, as explained below.

Mandatory Job Readiness and Health Risk Assessments Would Also Cause Coverage Losses

The Buttrey proposal also reportedly includes a new requirement that beneficiaries complete job readiness and health risk assessments as a condition of enrollment. This added paperwork would be both unnecessary and harmful. Montana’s HELP-Link program already targets a job readiness assessment and job training for beneficiaries who need it; it’s unclear what a mandatory assessment would do beyond imposing additional administrative costs on the state and likely causing beneficiaries who are unaware of or confused by the requirement to lose coverage.

No other state has a mandatory job readiness assessment as a condition of Medicaid eligibility, and only Wisconsin has received federal approval to require a health risk assessment (which the state has not yet implemented).[23] However, states that have given beneficiaries incentives to complete a health risk assessment have seen low participation and broad confusion.[24]

In Michigan, newly enrolled adult beneficiaries have to pay co-payments for most services, but their cost sharing is reduced if they complete a health risk assessment and agree to participate in certain activities. As of March 2018, fewer than 19 percent of beneficiaries who had been enrolled for at least six months had received credit for completing the assessment.[25] A 2016 survey found that of those who did complete a health risk assessment, only 0.1 percent reported that they did so in order to save money on co-pays, indicating very low beneficiary comprehension of the program.[26] Evaluations in Iowa have found similar results.[27]

The reasons why relatively few beneficiaries complete health risk assessments, despite the financial incentives to do so, likely include confusion about the rules and incentives, challenges with the paperwork itself, and concerns about the confidentiality of their health information. Even if completion rates were somewhat higher for mandatory job readiness and health risk assessments, thousands of Montanans would still lose coverage purely due to paperwork.

Work requirements and increased premiums would impose a variety of difficult administrative tasks on Montana: modifying eligibility systems, creating new systems for beneficiaries to document compliance with the new requirements, evaluating this large volume of documentation each month, informing beneficiaries of the new rules, training and/or hiring additional caseworkers to make determinations about exemptions and other new rules, and hiring additional staff to address appeals related to coverage denials.

States that are implementing or have considered similar Medicaid waivers estimate the cost at tens to hundreds of millions of dollars.[28] For example:

- Kentucky plans to spend $186 million in state fiscal year 2018 and an additional $187 million in 2019 to implement its approved waiver.

- Alaska projects that its proposed work requirement would cost the state $78.8 million over six years, including about $14 million per year in annual ongoing costs.

- A Pennsylvania state official testified that a proposed work requirement would cost $600 million and require 300 additional staff to administer.

- In Minnesota, counties (which determine Medicaid eligibility in that state) would have to spend an estimated $121 million in 2020 and $163 million in 2021 to implement proposed work requirements. Counties estimate that it would take an average of 53 minutes to process each exemption and 84 minutes to verify non-compliance and suspend Medicaid benefits, for example.

Montana allocated just $885,400 for HELP-Link’s outreach, trainings, and linkages to other services in fiscal year 2018 and $888,500 in 2019 — less than 0.5 percent of Kentucky’s estimated implementation costs and a small fraction of what other states have projected in ongoing administrative costs. Rather than spending administrative resources to add complexity and reduce coverage, purportedly to increase employment among Medicaid beneficiaries, Montana could instead invest more in the successful HELP-Link program. Additional resources for HELP-Link would likely allow the program to reach more people or add more workforce training options and work support services.

States that expanded Medicaid have seen dramatic drops in hospitals’ uncompensated care as more residents gain coverage. Expansion-state hospitals saw their uncompensated care costs drop by roughly half between 2013 and 2015. Policies that cause substantial coverage losses, including work requirements, would jeopardize these financial gains.[29]

Unlike other states proposing work requirements, Montana already has a nationally recognized workforce promotion program that provides training and subsidized employment to low-income adults who are looking for work or climbing a career ladder. Taking coverage away from people who don’t meet work requirements or pay premiums could undermine this success.

Proponents’ claim that work requirements promote families’ financial independence ignores the fact that Medicaid coverage makes it possible for some low-income adults to work in the first place.[30] “[A]ccess to affordable health insurance has a positive effect on people’s ability to obtain and maintain employment,” Kaiser Family Foundation researchers concluded from a comprehensive review of the available evidence, while lack of access to needed care, especially mental health care and substance use treatment, impedes employment.[31]

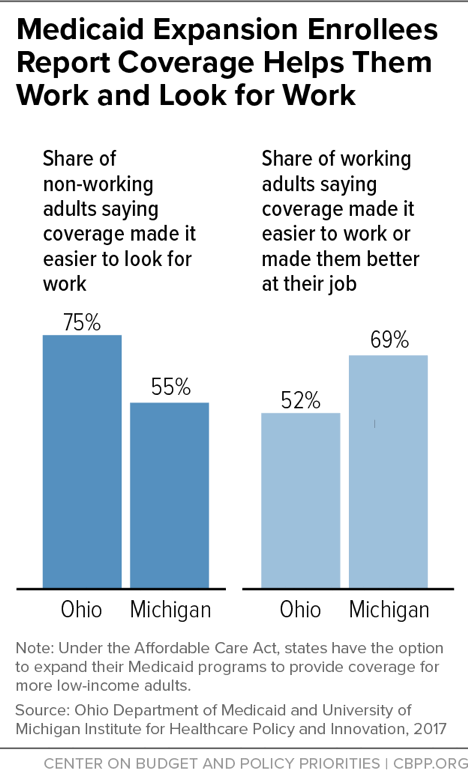

Low-income adult Medicaid enrollees have high rates of chronic conditions and mental illness.[32] Individuals with conditions like diabetes, heart disease, or depression may be able to hold a steady job if these conditions are treated and controlled, but work may become impossible if conditions go untreated. Beneficiaries themselves confirm the connection between coverage and work: majorities of non-working adults gaining expansion coverage in Ohio and Michigan said having coverage made it easier to look for work, while majorities of working adults said coverage made it easier to work or made them better at their jobs.[33] (See Figure 1.)

Finally, most jobs that Medicaid beneficiaries already have or are likely to get don’t pay enough for them to shift into subsidized individual market coverage or offer employer-based coverage, so they would still need Medicaid:

- Only 37 percent of workers with earnings in the bottom fourth of the wage distribution are offered health coverage by their employer, according to Labor Department data. And less than a quarter of the overall wage group actually obtain coverage, presumably in large part because required employee premium contributions are often higher than low-wage workers can afford.[34]

- Similarly, only 37 percent of full-time workers with family incomes below the poverty line (and only 13 percent of such part-time workers) are offered coverage.[35]

- Consistent with these data, in states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA, 42 percent of workers with family incomes below 138 percent of the poverty line (the income limit for Medicaid in these states) obtain health insurance through Medicaid, more than twice the share that obtain insurance through an employer.[36]