Seven states have approval from the Trump Administration to take Medicaid coverage away from people who don’t meet work requirements, with additional proposals pending.[1] Differences among these policies, such as who must report work or work-related activities, how they report, who is exempt, the number of hours required to comply, and the penalty for not reporting, will affect how many and how quickly enrollees lose coverage. But all work requirements will have the unintended consequences of taking coverage away from people who are already working or who should be exempt from the requirement based on disability or chronic illness. Moreover, Medicaid work requirements will not increase employment or improve health outcomes, contrary to the Administration’s claims.

Some have asked whether work requirements can be “fixed” — in other words, whether such policies can be implemented without unintended consequences and with positive impacts on employment. The answer is no.

Taking coverage away from people who don’t meet a work requirement is at odds with Medicaid’s “central objective” of providing affordable health coverage to people who wouldn’t otherwise have it, which means it’s not an allowable use of Medicaid waiver authority under section 1115 of the Social Security Act. But in Arkansas, the only state so far to implement work requirements for Medicaid, it’s increasingly clear that the policy is also failing on its own terms. Far more Arkansans are losing Medicaid coverage than are in the presumed target group of people not working and ineligible for exemptions, which means people who should remain eligible are losing coverage. Moreover, the work requirement isn’t promoting employment. While many Arkansas Medicaid beneficiaries are working, only a tiny percentage of those subject to the requirements — 0.5 percent in the latest month’s report — have newly reported work hours in response to the work requirement. And even many of those beneficiaries might have found jobs without the new policy or might have already been working.[2]

Work requirement policies can’t be fixed for several reasons. First, any work requirement will have the unintended consequence of taking coverage away from people who are already working or should be exempt due to illness, disability, or other factors. That’s because rules for reporting and claiming exemptions increase paperwork and red tape, which cause eligible people to lose coverage and become uninsured. Efforts to inform beneficiaries of the complex compliance requirements and the processes for reporting and claiming exemptions are certain to fall short, leaving people without the information and help they need to comply. In addition, working Medicaid beneficiaries often have low-wage jobs with volatile hours and little flexibility, so they may not be able to work a set number of hours each month — meaning that even people strongly attached to the labor force will lose coverage.

Second, work requirements are ineffective in promoting employment because they don’t accurately identify those who can work but aren’t working (often for reasons beyond their control), nor do they assess their needs or provide them with supports. And they can undermine work when people can’t get the health care they need to work or look for a job. Experience from the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program shows work requirements don’t significantly increase long-term employment and don’t reduce poverty. That’s even more likely the case with Medicaid: while TANF programs generally provide for at least some (albeit inadequate) supportive services that many low-income adults need in order to work, such as child care, job training, and transportation assistance, states implementing Medicaid work requirements aren’t required to provide any of that help.

Moreover, Medicaid is itself a work support. It makes affordable health coverage available to low-wage workers whose jobs don’t offer it and makes it possible for people with diabetes and other chronic illnesses to work by helping them control these conditions. Recent news reports from Arkansas provide stark evidence of how Medicaid work requirements can undermine their purported goals,[3] including a profile of a working beneficiary who lost his coverage due to reporting difficulties, couldn’t get his medications, and ended up losing his job because he couldn’t afford to keep his chronic illness in check.

Even if work requirements could somehow avoid unintended consequences, they would still do harm: among Medicaid beneficiaries who aren’t working and don’t qualify for exemptions, many face major barriers to work and have serious health needs.[4] But the unintended consequences can’t be avoided.

Paperwork and Red Tape Cause Eligible People to Lose Coverage

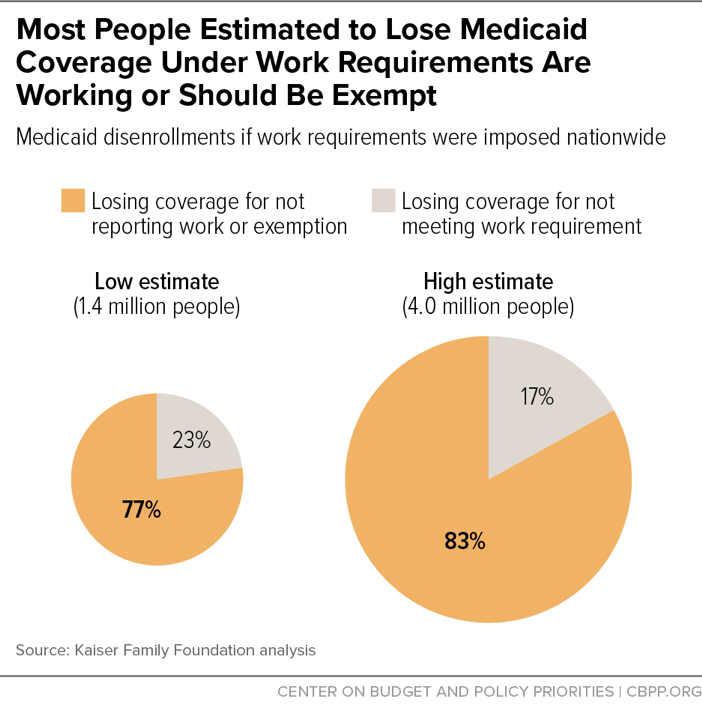

If implemented nationwide, work requirements would cause disenrollment ranging from 1.4 million to 4 million people among the 23.5 million adult Medicaid enrollees who are under 65 and not receiving Supplemental Security Income based on disability, Kaiser Family Foundation researchers estimate. Most of those losing coverage would be people who are already working or should be exempt but would lose coverage because of the increased red tape and paperwork inherent in work requirements.[5] (See Figure 1.)

The researchers reach these conclusions based on evidence from past eligibility restrictions in Medicaid. For example, when Washington State increased documentation requirements and made other changes that made it harder to enroll and stay enrolled, enrollment dropped sharply; and it rebounded when the state reverted to its prior processes.[6] Similarly, states reported large declines in Medicaid enrollment, particularly among children, in the months after 2006 federal legislation required states to ask families to prove their citizenship and identity when applying for or renewing their Medicaid coverage.[7] There was no evidence that those losing coverage were ineligible. Instead, eligible people found it difficult to obtain the necessary documents.[8]

When people who are already working or unable to work have trouble reporting their work hours or proving they are exempt, they lose coverage even though they are not the target of work requirements. This appears to be the case in Arkansas, where the number of people losing coverage exceeds the number who are already working or exempt from the work requirement. Overall, since implementation of the work requirement in June 2018, nearly 17,000 Arkansans have lost their Medicaid coverage, amounting to nearly 22 percent of all beneficiaries subject to the new policy. The main reason even more Arkansans haven’t lost coverage seems to be that most beneficiaries didn’t have to report any new information to comply with the work requirement: state data already showed they were working or qualified for exemptions. But over half of beneficiaries who weren’t exempt from reporting have lost coverage.

Some have treated Arkansas’ experience with work requirements as an implementation failure. In particular they’ve blamed the state’s requirement that beneficiaries report using an online portal, which has made it hard for many to comply given the state’s low internet access rate. But making timely reports every month and documenting hours or exemptions will be challenging for beneficiaries in all states with a work requirement even if beneficiaries can report by phone (which Arkansas beneficiaries can now do as of late December) or in person.[9]

Likewise, people coping with serious mental illness or physical impairments may face difficulties obtaining physician testimony, medical records, or other documents required to qualify for exemptions. Mental illness often affects the cognitive functions needed to navigate complex bureaucratic systems, making it hard for someone to qualify and often leading them to give up and drop out of the process.[10]

Studies of state TANF and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance (formerly food stamp) programs have found that people with disabilities, serious illnesses, and substance use disorders may be disproportionately likely to lose benefits, even when they should be exempt. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) requires states to provide “reasonable modifications” to ensure people with disabilities can participate in public programs, and work requirement waivers the Administration has approved require states to provide such modifications. Yet Arkansas has placed the burden on people with disabilities to know their rights under the ADA and to determine how to request accommodations. As a result, many people with disabilities are likely among those who have already lost coverage and are at risk of losing coverage in the future.[11] The same will likely occur in other states.

On top of these challenges, Medicaid beneficiaries must understand the complex rules on who must comply with the work requirement, who is exempt, how long exemptions last, and how to report work hours or potential exemptions. In Arkansas, good cause exceptions are available to those experiencing illness, family emergencies, or other reasons that can excuse compliance for one month, but again, beneficiaries need to be aware of these exceptions and how to apply for them. People experiencing homelessness often miss notices from the state because they lack a reliable address.[12] And those who lose coverage must know the rules on how to regain it, including when their penalty ends and how they can reapply for coverage.

Most Medicaid beneficiaries don’t directly interact with caseworkers when applying for or renewing coverage and will instead receive information about the work requirement through long, complex paper notices. Arkansas health plans and the state’s Medicaid agency have tried to inform beneficiaries of the new requirements through mailings, texts, emails, online videos, and phone calls, but there is still low awareness and understanding of the work requirement.[13] Most Arkansas beneficiaries participating in a focus group said they didn’t fully read the letter they received or understand the reporting requirements or the consequences of not complying.[14] Arkansas’ experience is consistent with the results of complex Medicaid incentive programs that try to promote healthy behaviors by decreasing enrollee cost-sharing, where extremely low program awareness among beneficiaries and confusion among those who were aware have rendered the programs ineffective, research has shown.[15]

What’s more, in some respects Arkansas implemented its policy in ways designed to reduce harm, compared to what other states are considering. First, Arkansas excluded some large groups from its work requirement policy altogether: people age 50 and older and parents of children under 18. Both these groups face special challenges complying with work requirements. But most other states with pending or approved work requirement waivers would apply the requirements to at least some older adults, and several would apply them to parents. These states could see even larger coverage losses among eligible people.

Second, Arkansas uses available state data to exempt a large share of beneficiaries from having to report or claim an exemption. In November, the state exempted 83 percent of people subject to the work requirement based on criteria such as prior medical exemptions or sufficient monthly earnings. Among those who had to report, 78 percent did not report 80 hours of work or work-related activities — suggesting that coverage losses in Arkansas would have been far greater without automated determinations of exemptions and compliance.[16] (As discussed above, if those exempt from reporting were instead required to report, it’s likely that many would fail to do so, even those who would meet the hours threshold or qualify for an exemption.) Other states with approved and pending waivers don’t plan to automate the determination of exemptions and compliance to nearly as great an extent. For example, Kentucky will only exempt a narrower group of workers from reporting. In addition, in Kentucky, failing to report 80 hours of work or work-related activities in any month will result in loss of coverage unless the beneficiary makes up the missed hours the following month (versus Arkansas’ policy, which takes coverage away from those who fail to report sufficient hours for three months).

Most non-elderly adult Medicaid beneficiaries already work, but in low-wage jobs that generally do not offer health insurance. The two industries that employ the most Medicaid enrollees potentially subject to work requirements are restaurant/food services and construction, with large numbers also working in grocery stores, department and discount stores, and the home health industry.[17] These industries are characterized by volatile hours and little flexibility, so beneficiaries may not be able to work the required number of hours every month. Illness, family emergencies, or a lack of child care or transportation can also lead to job loss or shortfalls in hours.

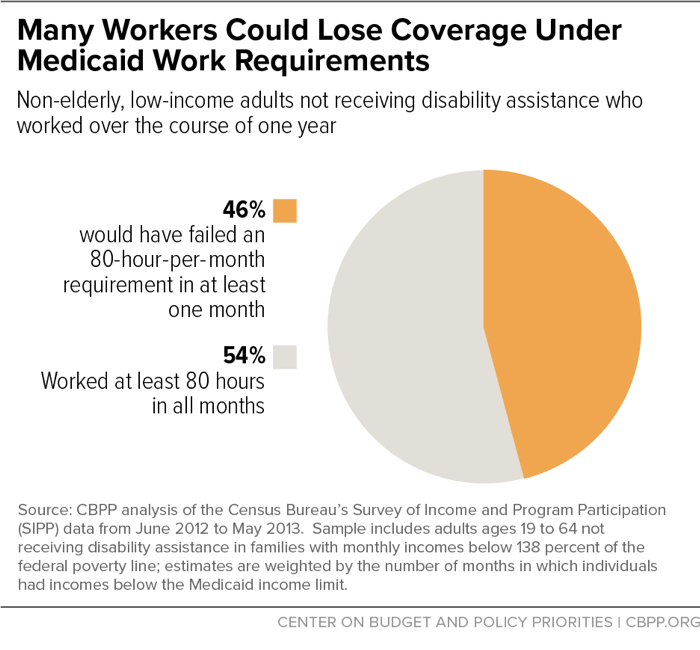

Most states planning or considering work requirements are proposing that beneficiaries work at least 80 hours each month. Our analysis shows the difficulties that low-wage work presents in meeting such a rigid work requirement. [18] We found that 46 percent of low-income working adults who could be subject to Medicaid work requirements would be at risk of losing coverage for one or more months because they wouldn’t meet the 80-hour requirement in every month. (See Figure 2.) Even among people working 1,000 hours over the course of the year — enough on average to meet the 80-hour monthly requirement — 1 in 4 would be at risk of losing coverage for one or more months because they would not meet the minimum in every month. This is in addition to those who would lose coverage because of the red tape and paperwork inherent in work requirement policies. (Notably, the Kaiser estimates cited above take into account coverage losses among low-wage workers due to reporting burdens, but not due to volatile hours.)

Other researchers reach similar conclusions about the volatility of low-wage work, finding that 80 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries aged 18 to 49 without a dependent child under 6 were in the labor force at some point over a two-year period from 2013 to 2014. [19] But while about half of these beneficiaries consistently worked 20 hours a week, the rest either fell below that threshold or were out of work at some point over the two-year period, which would put them at risk of losing coverage. The researchers also found that looking at work status for just one month understated the share of working beneficiaries relative to their findings from work activities examined over a two-year period. In other words, many people not working in a specific month do work over the course of a longer period, suggesting a share of non-workers in the monthly data are between jobs.

Taking coverage away from people who don’t work a set number of hours because they are between jobs, can’t make a rigid monthly hours target, or have temporary barriers such as illness or a lack of child care does nothing to encourage work; it just deprives working people of coverage and access to care.

Among the justifications that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) gives for allowing Medicaid work requirements is that they will lead to gains in employment and “financial independence.” Leaving aside the fact that most beneficiaries are already working but in jobs that don’t offer affordable health coverage, a significant body of research on the impact of TANF work requirements shows that such requirements don’t significantly increase long-term employment and don’t reduce poverty.[20] There’s no reason to believe a Medicaid work requirement would have a better result, and since states need not provide any work supports such as training, transportation, or child care (as they do with TANF), the results could be worse.

CMS argues that penalizing beneficiaries by taking their coverage away is necessary “to create an effective incentive for beneficiaries to take measures that promote health and independence.”[21] In other words, CMS claims that the only way to increase work among Medicaid beneficiaries is to take their coverage away if they don’t work. But research on work requirements in federal cash assistance programs — TANF and its precursor, Aid to Families with Dependent Children — finds that employment increases for those subject to work requirements are generally modest, fade over time, and don’t move many families out of poverty.[22] For example, a synthesis of results from randomized trials of 13 programs imposing work requirements in cash assistance programs finds that employment rose by modest amounts in the first two years, but these gains generally faded by year 5 (to an average effect of about 1 percentage point).[23] Meanwhile, stable employment proved the exception, not the norm, and few enrollees transitioned out of poverty as a result of the work requirements.

For several reasons, work requirements in Medicaid will likely have equally or more disappointing results. Sixty percent of adult Medicaid enrollees potentially subject to work requirements already work, and more than 80 percent of the remainder are students or report that they are unable to work due to a disability, serious illness, or caregiving responsibilities. This suggests limited scope for work requirements to increase work participation.[24]

Meanwhile, cash assistance programs generally provide at least some (albeit inadequate) resources for the supportive services that many low-income adults need in order to work, such as child care, job training, and transportation assistance. The more successful experimental programs described above coupled work requirements with robust work supports. In contrast, Medicaid work requirements won’t help the small share of beneficiaries who aren’t working but who could work with supports such as child care, transportation, or job training, because these supports aren’t available to beneficiaries. Federal Medicaid funds can’t pay for these supports, which many Medicaid beneficiaries need to work a set number of hours each month. Other state workforce programs don’t have the resources to meet the needs of low-income Medicaid beneficiaries who often live in rural areas without public transportation, who lack job skills, and who are taking care of children and other family members.

Moreover, it makes no sense to target people who can work but are between jobs, because they will likely find work on their own and move out of the target group. States would be better off implementing a program like Montana’s Health and Economic Livelihood Partnership Link (HELP-Link), a work promotion program for Medicaid beneficiaries that targets state resources toward reducing barriers to work and helping people find jobs, rather than toward creating new bureaucracy to track employment and exemption paperwork for all enrollees.[25]

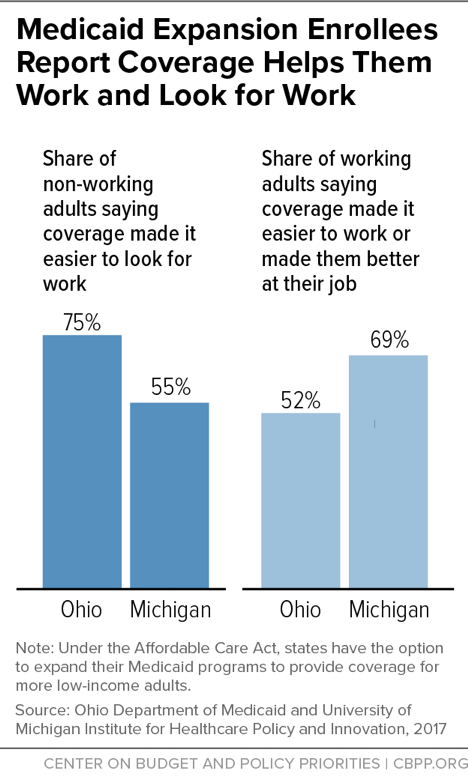

The Trump Administration’s promotion of work requirements as a way of promoting financial independence ignores the fact that Medicaid coverage makes it possible for many low-income adults to work in the first place. As Kaiser Family Foundation researchers concluded from a comprehensive review of the available evidence, “access to affordable health insurance has a positive effect on people’s ability to obtain and maintain employment,” while lack of access to needed care, especially mental health care and substance use treatment, impedes employment.[26]

Low-income adult Medicaid enrollees have high rates of chronic conditions and mental illness; for example, 69 percent of adults enrolled through Michigan’s Medicaid expansion (under the Affordable Care Act) have at least one chronic physical or mental health condition.[27] Individuals with conditions like diabetes, heart disease, or depression may be able to hold a steady job if these conditions are treated and controlled, but work may become impossible if conditions go untreated. Beneficiaries themselves confirm the connection between coverage and work. Majorities of non-working adults gaining coverage through the Medicaid expansion in Ohio and Michigan said having health care made it easier to look for work, while majorities of working adults said coverage made it easier to work or made them better at their jobs.[28] (See Figure 3.)

Finally, most jobs that Medicaid beneficiaries already have or are likely to get are low wage, neither paying enough for them to shift into subsidized individual market coverage nor offering employer-based coverage, so they would still need Medicaid. Among workers with earnings in the bottom fourth of the wage distribution, only 37 percent are offered health coverage by their employer, according to Labor Department data. And less than a quarter of the overall wage group actually obtain coverage, presumably in large part because required employee premium contributions are often higher than low-wage workers can afford.[29] Similarly, only 37 percent of full-time workers with family incomes below the poverty line (and only 13 percent of such part-time workers) are offered coverage.[30] Consistent with these data, in states that expanded Medicaid under the ACA, 42 percent of workers with family incomes below 138 percent of the poverty line (the income limit for Medicaid in these states) obtain health insurance through Medicaid, more than twice the share that obtain insurance through an employer.[31]

Medicaid work requirements can’t be fixed: other states that implement work requirements will see the same unintended consequences as Arkansas is experiencing. After evaluating the initial data from Arkansas, the non-partisan Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission recommended that the Administration immediately pause on allowing any more people to lose coverage in Arkansas as well as on approving work requirements in other states.[32] Both the Trump Administration and state policymakers should heed that recommendation.