The Michigan Senate is voting on a bill today that would take coverage away from Medicaid enrollees who don’t meet rigid work requirements;[1] the House of Representatives will consider the bill next if it passes the Senate. The Senate is moving so rapidly — a new version of the bill was unveiled and passed out of its only committee of referral April 18 — that neither the legislature nor the state’s Department of Health and Human Services has had time to produce a comprehensive estimate of the bill’s impact on health coverage, access to health care, and the state’s finances.

However, analyses of similar proposals from other states suggest that the Michigan bill would result in:

- Large coverage losses. All states that have released projections of the impact of proposed work requirements forecast that they would lead to Medicaid coverage losses. To provide a sense of magnitude, Kentucky estimates that its Medicaid waiver, whose centerpiece is a work requirement policy similar to (but in some ways less stringent than) Michigan’s proposal, would eventually lead to a 15 percent drop in adult Medicaid enrollment. A comparable coverage reduction in Michigan would be in the range of 150,000 people. Coverage losses under Michigan’s proposal would likely have especially harmful impacts on enrollees’ health, because it would lock them out of coverage for a full year after failure to meet the work requirement.

- Coverage losses among working Michiganders. Counterintuitively, many of those losing coverage would likely be workers. Most Michigan Medicaid enrollees who would be subject to the new policy already work, but often in unstable jobs with fluctuating hours, in industries like retail, restaurant work, home health, or construction or in seasonal jobs such as in the state’s tourism industry. Nationally, we estimate that even among low-income workers who would meet Michigan’s proposed 29-hour-per-week work requirement on average over the course of a year, 25 percent would be at risk of losing coverage because they don’t meet the requirement every month.

- Added costs for the state and hospitals. The Michigan Senate Fiscal Agency estimates it would cost the state between $20 million and $30 million a year to administer a work requirement. And, by increasing the number of uninsured, the bill would also increase the amount of uncompensated care that hospitals provide, which could increase state costs for public hospitals.

Proponents claim the Michigan proposal is intended to support employment, but it provides no new money to expand existing workforce development programs or create a new work supports program. If Michigan wants to do more to promote and support work, it should instead explore other strategies, like Montana’s workforce promotion program (“HELP-Link”), which would support employment among Medicaid enrollees without endangering the state’s progress in expanding coverage and improving health. Since Michigan adopted Medicaid expansion, its uninsured rate has fallen by 45 percent, expansion enrollees report large improvements in access to care, and they say health coverage has helped them seek and maintain employment.[2]

The Michigan legislation requires the state to submit a Medicaid waiver proposal to the Trump Administration by October 1 to impose a work requirement on up to 1 million non-elderly adult Medicaid beneficiaries. This includes roughly 700,000 enrollees who have coverage because the state expanded Medicaid as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), and 300,000 extremely low-income parents who are covered under the state’s pre-ACA eligibility guidelines.

The bill’s centerpiece is a requirement that beneficiaries between ages 19 and 64 work or engage in other “qualifying” activities for 29 hours per week on average each month — equal to almost 125 hours a month — or lose their Medicaid coverage.[3] This exceeds the 80-hour-a-month requirement that the Trump Administration has approved in Arkansas and Kentucky, and the bill’s list of qualifying work activities is more limited; in particular, other states count job search as a qualifying activity, whereas Michigan allows it only in counties with high unemployment rates. The bill includes a list of narrow exemptions for people who, for example, meet the state’s SNAP (food stamps) work requirement, have a long-term disability, are pregnant, medically frail, are a caretaker for a child under age 6 (although only one parent per child may be exempt), or are age 19 or 20 and were formerly in foster care.

Every month, beneficiaries would have to verify that they are meeting the requirements by the fifth of the month to maintain their coverage. If they missed that deadline, they would be treated as not meeting the requirement even if they later showed they did meet it. And anyone who lost coverage for failing to meet the requirements would not be able to regain coverage for a full year — a coverage “lockout” of unprecedented length in Medicaid.

The Michigan Senate is voting on the bill before its Fiscal Agency, the state’s Department of Health and Human Services, or independent researchers have had a chance to conduct a comprehensive analysis of its impact on beneficiaries, the state’s finances, and access to health care in the state. Such an analysis would likely find the following:

All states with work requirement proposals project that significant numbers of people will lose Medicaid as a result. Kentucky, the first state in which the Trump Administration approved a Medicaid work requirement, projects that its waiver will ultimately cause 15 percent of adult enrollees to lose coverage.[4] While Kentucky’s waiver includes features not in the Michigan bill that would make it harder for people to maintain their coverage, its work requirement entails a lower hours-per-week threshold, more exemptions, and no lockout period. In Michigan, a 15 percent coverage loss for adult enrollees would translate into about 150,000 enrollees in a typical month.[5]

The coverage losses from the waiver would likely have severe adverse impacts on health. In a 2016 state survey, 83 percent of enrollees in Michigan’s Medicaid expansion (the Healthy Michigan Plan) agreed or strongly agreed that without Medicaid coverage they would not be able to go to the doctor.[6] That’s consistent with a large and growing body of research finding that Medicaid expansion has significantly expanded access to preventive, primary, and other important health care services.[7]

A study based on the same survey found that the large majority of Healthy Michigan enrollees — and 80 percent of enrollees not working at the time of the survey — have a chronic physical or mental health condition such as diabetes, hypertension, or depression. (See Table 1.) People with these conditions require regular access to medications and other treatment to maintain their health, so even brief interruptions in coverage and access to care can be harmful. But under Michigan’s proposal, enrollees who fail to meet the work requirement, including those with serious chronic conditions, would be locked out of coverage for a full year.

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| |

Share with Specified Condition |

|---|

| |

All enrollees |

Working at time of survey |

Not working at time of survey |

|---|

| Any chronic condition |

69% |

62% |

80% |

| Diabetes |

11% |

9% |

15% |

| Hypertension |

31% |

25% |

42% |

| Cardiovascular disease |

10% |

7% |

14% |

| Asthma |

17% |

15% |

19% |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

11% |

8% |

15% |

| Cancer |

4% |

3% |

5% |

| Any mental health condition |

32% |

25% |

43% |

| |

|

|

|

| Functional impairment (physical) |

23% |

13% |

37% |

| Functional impairment (mental) |

20% |

12% |

32% |

| |

|

|

|

Coverage Losses for Workers and People with Disabilities, Among Others

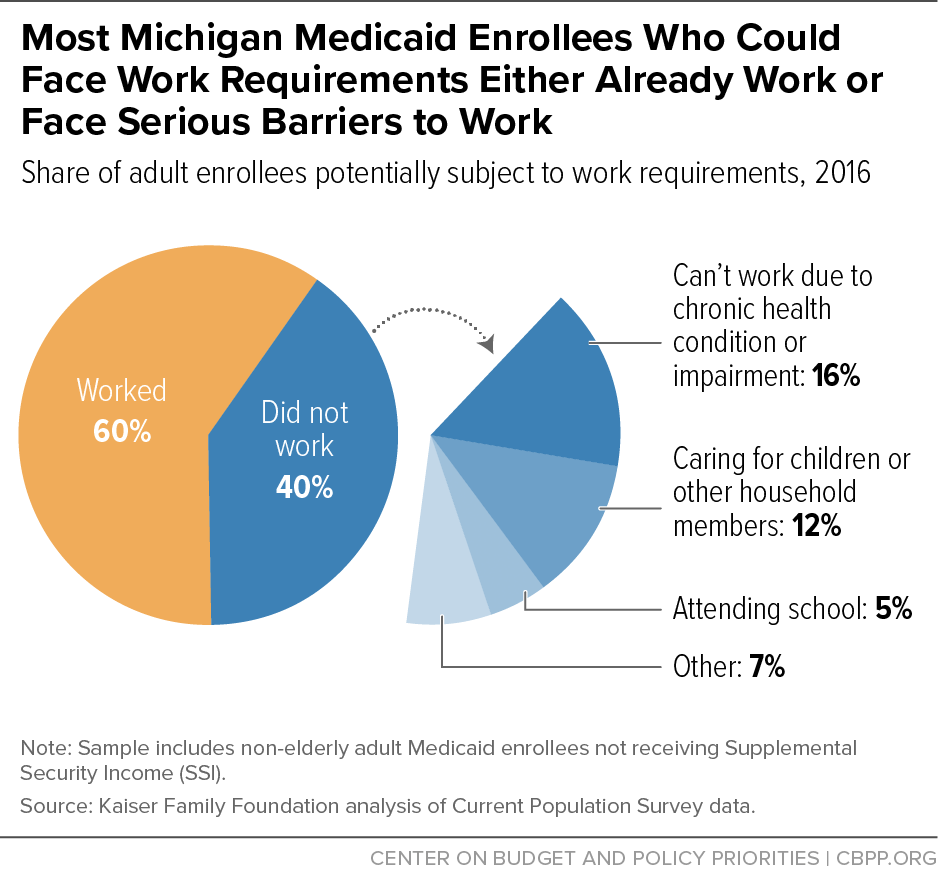

Sixty percent of Michigan Medicaid enrollees who could be subject to work requirements work; of those not working, most live in working families, and more than 80 percent are students or report that they are unable to work due to illness, disability, or caregiving responsibilities, according to Kaiser Family Foundation estimates.[8] (See Figure 1.) While likely not the intended targets of the policy, people in these groups would be at significant risk of losing coverage:

-

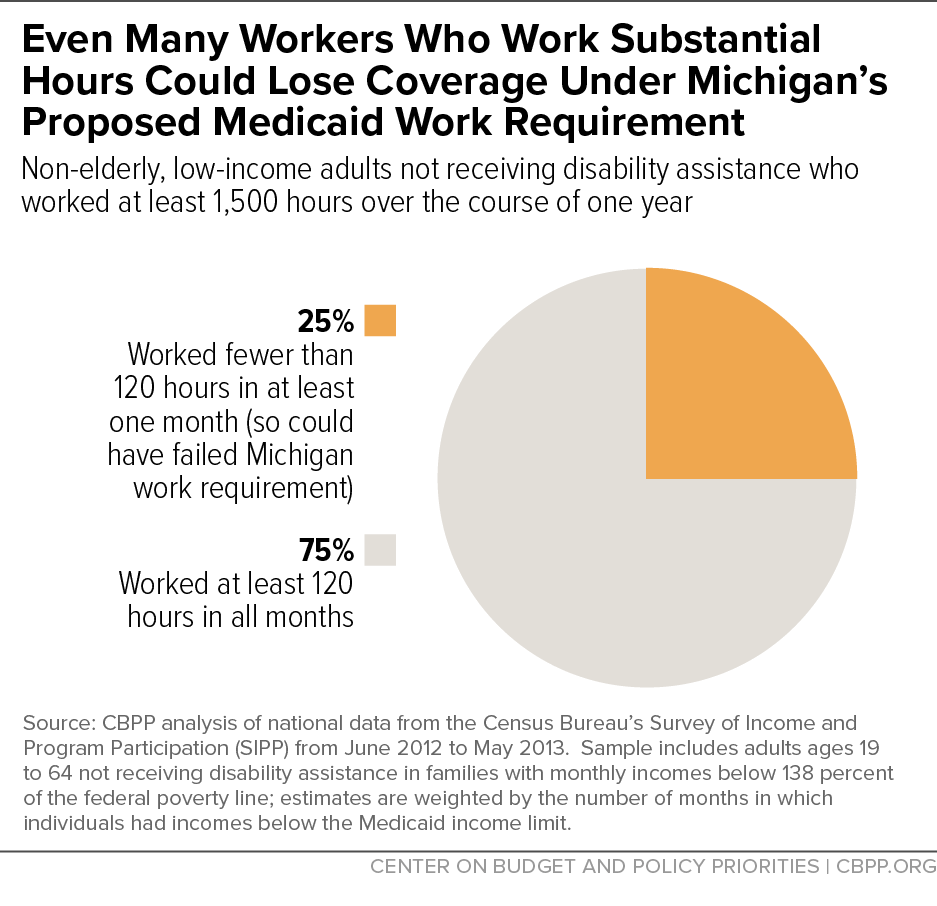

Low-income workers. Analyzing national data on low-income adults who could be subject to work requirements, we find that most work substantial hours over the course of the year, but many do not work consistent hours from month to month as a work requirements policy like Michigan’s proposal requires. As a result, more than half of the low-income workers who could be subject to Medicaid work requirements would be at risk of losing coverage under a 29-hour-per-week requirement. Even among those working at least 1,500 hours over the course of the year and thus meeting the 29-hour standard on average, 1 in 4 (25 percent) would be at risk of losing coverage because they do not meet the requirement every month.[9] (See Figure 2.)

These findings reflect the reality of low-wage work. The industries that commonly employ Medicaid enrollees — such as retail, restaurant/food services, home health, and construction — generally feature variable hours, above-average levels of involuntary part-time work and irregular scheduling, and minimal flexibility. As a result, any illness, family emergency, or child care or transportation disruption can lead to job loss and a spell between jobs. Under Michigan’s policy, any such event could then lead to loss of health coverage for an entire year as well.

-

People with disabilities, older people, and other vulnerable groups. While the Michigan bill exempts people who are medically frail or have medical conditions that prevent them from working, some people with disabilities and serious illnesses would inevitably fall through the cracks and lose coverage. This could occur because they don’t meet the criteria for limited exemptions, don’t understand that they do qualify for an exemption, or struggle to provide the documentation proving that they qualify. Bearing out these concerns, studies of state SNAP and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) programs[10] have found that people with disabilities, serious illnesses, and substance use disorders may be disproportionately likely to lose benefits due to work requirements, even when they should be exempt.[11]

Older enrollees also would likely be disproportionately affected. Nationally, nearly two-thirds of Medicaid enrollees potentially subject to work requirements who are under age 50 work, but work rates fall for those over 50, who are more likely to have serious health conditions, and only a minority of 60- to 64-year-old enrollees work.[12] Because the Michigan proposal applies work requirements up to age 64, older adults, including people in their early 60s who decided to retire prior to age 65 because of their health, could lose their health coverage if unable to return to work for 29 hours per week.

- Michiganders enrolled in post-secondary education. While the Michigan bill exempts full-time students who are emancipated minors or whose parents qualify for Medicaid, all other students would be subject to the work requirement. Vocational and job training would count toward the 29-hour weekly requirement, as would other education if it is deemed directly related to employment. Students whose education counts as a qualifying activity would have to go to school, work, and/or engage in other activities an average of 29 hours per week to maintain their health coverage — while other students would have to work 29 hours a week and go to school. If state policymakers aim to promote economic mobility, forcing students to work this many hours to maintain their health coverage is counterproductive, making it less likely they will succeed in school and increase their earning potential.

Added Costs for Administration and Uncompensated Care

The Michigan Senate Fiscal Agency’s analysis of the bill notes, “it is not possible to provide anything approaching a precise estimate of cost and savings. As a result, this fiscal analysis is vague.”[13] But it does estimate that Michigan would incur between $20 million and $30 million in new administrative costs per year just to implement the new requirements.

The Senate Fiscal Agency also notes that many people losing Medicaid coverage due to the bill would end up uninsured but would still seek care, mainly at hospitals. This would reverse a trend of declining uncompensated care since Medicaid expansion took effect in April 2014: from 2013 to 2015, Michigan hospitals saw uncompensated care costs fall by more than half as a share of their budgets.[14] While the Senate Fiscal Agency does not attempt to quantify the impact on hospital or state uncompensated care costs, the effects could be large. The drop in hospital uncompensated care costs since 2013 amounts to $571 million; reversing even 15 percent of that decline would cost hospitals $85 million annually.

Though the bill’s supporters claim that its goal is to support work, it would not direct any new money to existing workforce development programs or create new work support programs. Instead, it simply states that the “department must first direct recipients to existing resources for job training or other employment services.” This means the bill effectively requires the department to spend money on tracking, verification, and paperwork but not to provide any new work supports to help beneficiaries maintain coverage.

Adding employment supports to the bill would raise its cost dramatically. A fiscal analysis of a work requirement proposal in Virginia, which has a smaller Medicaid caseload than Michigan, found that case management costs would total $162 million a year and employment support services $50 million a year.[15] Importantly, the federal government would not provide matching funds for the cost of these services; they would be entirely state-funded.

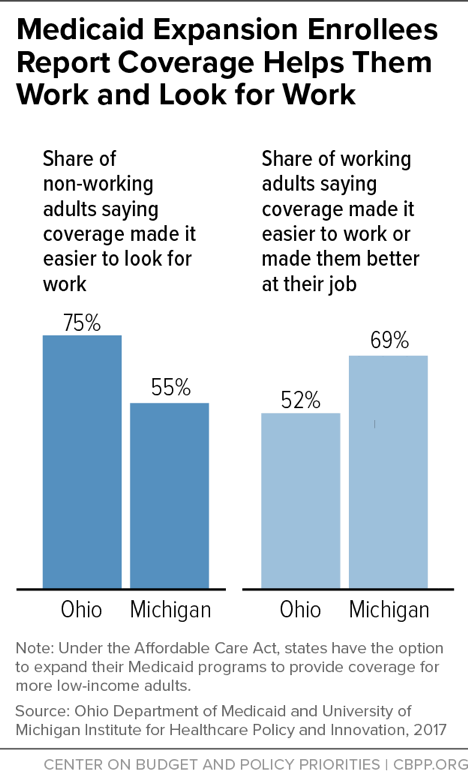

Nearly 70 percent of employed Healthy Michigan beneficiaries said gaining Medicaid coverage helped them do better at work, and more than half of unemployed beneficiaries said having health coverage made it easier to look for work, according to surveys by University of Michigan researchers as part of the state’s evaluation of the program.[16] (See Figure 3.)

These findings are similar to those from a survey of Medicaid expansion beneficiaries in Ohio. There, 75 percent of those who were unemployed and looking for work when they gained coverage said that Medicaid made the task easier; among those who were employed, half said that Medicaid made it easier to stay working.[17]

As these findings show, health coverage is an important work support: having health care helps people work and look for work, and taking it away will likely make it harder for some to keep and find work, setting off a vicious cycle for some working enrollees.[18] Health problems are a common cause of job loss among low-wage workers, in part because (as discussed above) low-wage jobs often offer little flexibility to take time off due to illness. In states with work requirements, some workers who lose their jobs due to health setbacks may then lose their health coverage and access to treatment as well, which would make it far harder for them to regain their health and their employment. Similarly, loss of coverage due to failure to document sufficient hours of work may lead to deteriorating health, causing job loss.

Montana’s workforce promotion program (“HELP-Link”), which links Medicaid enrollees who are looking for work or better jobs with services such as career counseling, on-the-job training programs, and subsidized employment avoids these harmful and unintended consequences.[19] In its first two years, the program has shown promise and has generated strong voluntary take-up among enrollees, likely because the state has engaged in intensive outreach, offered meaningful services, and provided trainings to service providers and partners on meeting the needs of low-income Medicaid enrollees.

By investing in outreach and services for individuals who are able to work but have barriers to finding and holding a job, Montana targets state funds to services that could actually increase employment and income for low-income people. In contrast, work requirements force states to spend taxpayer dollars on new systems to monitor and cut Medicaid coverage from many people who are not the target of the policy — those who are already working or may never be able to work — with deeply harmful consequences.

Moreover, research has generally found that work requirements in other programs have only modest and temporary effects on employment and neither increase long-term employment nor reduce poverty.[20] Results in Medicaid are likely to be just as disappointing and could be worse, since state Medicaid programs generally are not well equipped to provide work support services, which are already oversubscribed in most states and for which Michigan’s proposal provides no new resources.