Policymakers of both parties have resumed discussions about legislation to strengthen the individual market for health insurance, reportedly with the goal of reaching an agreement by March 23, the deadline for Congress to pass new appropriations legislation.[1] A starting point for these discussions has been two bipartisan bills negotiated last fall: legislation introduced by Senators Lamar Alexander and Patty Murray that would restore cost-sharing reduction (CSR) payments to insurers, among other changes, and legislation introduced by Senators Susan Collins and Bill Nelson that would provide federal funding for state reinsurance programs.[2]But the health insurance landscape has shifted since last year, and simply adopting last year’s bipartisan bills, without significant changes, would do more harm than good.

Since these proposals were initially negotiated, there have been a number of important developments:

- Congress repealed the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) individual mandate (the requirement that most people have health insurance or pay a penalty) beginning in 2019. By reducing incentives for healthier people to sign up for coverage, repeal of the mandate will weaken the individual market risk pool, raise premiums, and increase the number of uninsured.

- The Trump Administration has proposed new regulations that would further weaken the individual market risk pool and increase premiums. Most significant, it is proposing to let insurers offer “short-term” health plans lasting up to one year that are exempt from the ACA’s consumer protections, including its prohibition on discrimination based on pre-existing conditions and its requirement to cover essential health benefits.

- The market has largely adjusted to the Trump Administration’s decision to end CSR payments, and the transition went considerably more smoothly than many experts anticipated. Ironically, ending CSR payments has helped the market weather some of the Administration’s other harmful actions. That’s because, as explained below, eliminating CSR payments resulted in increased subsidies for many consumers, making coverage more affordable and more attractive.

The sponsors of last year’s bipartisan stabilization bills generally agreed that the goals of the legislation were to make coverage more affordable for consumers, including by strengthening the individual market risk pool, and to maintain or increase consumer choice, including by encouraging insurers to participate in the market. In adapting last year’s bills to the current environment, policymakers must meet three tests to advance these goals.

-

Avoid making coverage more expensive for moderate-income consumers. Now that the market has adapted to the Administration’s decision not to pay CSRs, restoring these payments — without compensating adjustments in consumer subsidies, as Senator Murray has proposed — would increase premiums or cost sharing for up to 3.3 million moderate-income consumers (up to 36 percent of all HealthCare.gov consumers), in many cases by over $1,000 per year. In addition to the direct harm to those affected, making coverage less affordable would likely decrease enrollment, further weakening the individual market risk pool and compounding the damage from mandate repeal.

Meanwhile, the reinsurance funding that the Collins-Nelson bill would provide would be beneficial on its own, but House Republicans are reportedly proposing to offset its cost by restoring CSRs.[3] To be sure, such a package would make coverage more affordable for people with incomes above 400 percent of the poverty level. But it would do so at the expense of those with incomes below 400 percent of the poverty level — a harmful and unnecessary tradeoff.

- Address the greatest risks to the individual market. Without changes, neither Alexander-Murray nor Collins-Nelson would address the most serious outstanding threat to the individual market, the Administration’s recent regulatory actions expanding insurance plans that operate outside the ACA’s rules and protections. The short-term plans rule, in particular, may not only raise premiums but also risks leading some insurers to pull out of the individual market. Failing to block the proposed expansion of short-term plans would result in a “stabilization” package that ignores the major near-term risk to individual market stability.

- Avoid weakening consumer protections or coverage. The Administration is reportedly demanding that any stabilization bill include a measure allowing insurers to charge older people higher premiums. There is also a risk that policymakers may seek to offset the cost of federal reinsurance funding with policies that would make it harder for individual market consumers to access or maintain coverage, such as those House Republicans proposed as offsets for children’s health coverage last year. But a stabilization bill should not be used as a vehicle for policy changes or offsets that would weaken the ACA’s protections for people with serious health needs or make it harder to access coverage. Not only would such changes directly harm those affected, some could undermine the goals of a stabilization bill. Policies that make it harder for people to enroll in coverage tend to disproportionately discourage healthier consumers, worsening the individual market risk pool and increasing premiums.

Beyond these principles, there are larger opportunities to build on the ACA’s progress in expanding coverage, improving affordability, and strengthening consumer protections, as a number of recently introduced bills aim to do.[4] But whether a limited, bipartisan stabilization bill advances the goal of strengthening the individual market will depend on whether it meets the tests above.

This principle might seem non-controversial: policymakers of both parties agree that the goal of a stabilization bill is to make coverage more affordable, not less. Yet, one of the major proposals on the table — restoring CSR payments to insurers — would result in higher premiums, higher cost sharing, or both for millions of moderate-income consumers. That’s because the Trump Administration’s decision to stop these payments has had the effect of making coverage more affordable for many consumers who are eligible for premium tax credits.

Under the ACA, insurers are required to provide reduced cost sharing (lower deductibles, co-pays, and coinsurance) to lower-income consumers who enroll in “silver” tier marketplace plans; CSR payments are supposed to compensate insurers for providing this reduced cost sharing. With the Administration having halted these payments, insurers in most states are instead defraying their costs by charging higher silver plan premiums (a practice referred to as “silver loading”).

Because of the structure of the ACA’s subsidies, that shift in how insurers are compensated for cost-sharing assistance results in more affordable coverage options for many consumers. The ACA’s premium tax credits are based on the “sticker price” premium of a typical silver plan where a person lives, but consumers can also use these tax credits to purchase bronze (lower sticker price, higher deductible) or gold (higher sticker price, lower deductible) plans. Their net premium is the difference between the sticker price premium for the plan they select and their tax credit.[5] Because of the Administration’s decision to halt CSR payments, silver plan premiums — and therefore premium tax credits — increased more rapidly than bronze or gold plan premiums for 2018. The result is that many subsidized consumers can now purchase bronze plans with very low net premiums, or can purchase lower-deductible gold plans for less than they paid last year for silver plans.[6]

Most consumers with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line are still better off purchasing silver plans, because that lets them take advantage of the generous cost-sharing assistance they are eligible for in those plans. But people who are eligible for tax credits but not for significant cost-sharing assistance — those with incomes between 200 and 400 percent of the poverty line (about $24,000 to $48,000 for a single adult) — can now purchase plans with lower premiums, lower cost sharing, or both, as a result of the Administration’s decision. Meanwhile, unsubsidized consumers can largely avoid the premium increases resulting from that decision by purchasing bronze or gold or, in most states, by purchasing silver plans outside of the ACA marketplaces. (In most states, insurers increased premiums only for marketplace silver plans to account for the loss of CSRs, leaving similar plans offered outside the marketplaces unaffected.) Even before the Administration’s decision to end CSR payments, most unsubsidized ACA individual market consumers enrolled outside of the marketplaces, and the majority of on-marketplace unsubsidized consumers enrolled in non-silver plans.

This dynamic was understood prior to the Administration’s decision to stop CSR payments, with the Department of Health and Human Services, Urban Institute researchers, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), and others all predicting that ending CSR payments would ultimately reduce costs for consumers.[7] But most experts predicted an extended and disruptive transition before those gains would be realized. For example, CBO forecast that halting CSR payments would result in “about 5 percent of people liv[ing] in areas that would have no insurers in the nongroup market in 2018.” The bipartisan Alexander-Murray bill, introduced about a week after the Administration’s decision, aimed to restore CSR payments quickly enough to avoid these consequences.

But Senate leadership declined to bring the Alexander-Murray bill to a vote at that time. And — thanks in large part to state regulators’ timely intervention — the market adjusted to the loss of CSRs more quickly and smoothly than most experts anticipated. Insurers in states accounting for about 85 percent of marketplace enrollees incorporated the loss of CSRs into their silver plan premiums for 2018, and more states will likely follow this approach for 2019.[8] Contrary to concerns about bare counties, consumers everywhere in the country have 2018 coverage options through the marketplace.

Now that the market has adjusted to the loss of CSRs, restoring these payments — without compensating improvements in subsidies — would have significant adverse effects for consumers. Based on 2017 enrollment patterns, between 1.6 million and 3.3 million consumers in HealthCare.gov states — or between 18 percent and 36 percent of all marketplace consumers in these 39 states — could face higher costs if CSR payments are restored next year.[9] (See the appendix for an explanation of these estimates and state-by-state data.)

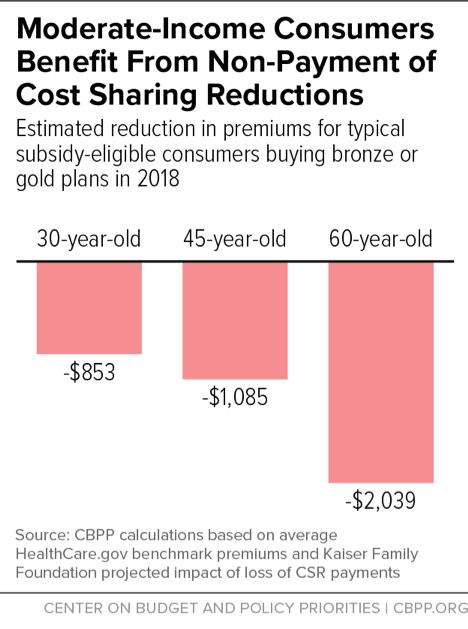

And the amounts at stake are sizable. Based on Kaiser Family Foundation estimates of the impact of CSRs on silver plan premiums, the Administration’s cut-off of CSRs is saving a typical subsidy-eligible 45-year-old $1,085 in premiums this year, provided that he or she purchases either a bronze or gold plan.[10] Savings are larger for older people, who face higher base premiums; for example, a typical subsidy-eligible 60-year-old is saving $2,039 this year, and would see a premium increase of similar magnitude next year if CSR payments were restored. (See Figure 1.) CBO estimated that halting CSR payments would cost the federal government more than $10 billion per year, and the Administration is touting the federal savings that would result from reversing its decision.[11] But these savings would come from reducing total subsidies (tax credits plus cost-sharing assistance), and therefore increasing total costs, for moderate-income consumers.[12]

Of course, halting CSR payments was not anyone’s preferred strategy for making coverage more affordable for consumers. Among other problems, the resulting affordability improvements are inconsistent across and within states, depending on state actions and insurer pricing decisions, and many consumers were likely confused about what plan they should select given premium changes, although consumers are likely to understand their options better with time.

Senator Murray has proposed a preferable alternative, in which CSR payments would be restored, but the federal savings would be used to directly improve affordability for moderate-income consumers.[13] For example, legislation restoring CSR payments could expand and improve cost-sharing assistance for people with incomes between 200 and 400 percent of the poverty line, ensuring that these consumers retain access to more affordable, lower-deductible plans even if premium tax credits fall. Or, it could increase premium tax credits, for example, by basing them on the cost of gold rather than silver plan coverage, maintaining the higher subsidies resulting from silver loading, but with more consistent increases across the country. (Bills taking these approaches have been introduced in both the House and Senate.[14])

Absent such an approach, however, restoring CSR payments would likely harm millions of people. It would also undermine the goals of stabilization legislation by harming the individual market risk pool. This year, higher subsidies helped make up for the Trump Administration’s outreach cuts and other actions undermining the marketplaces, contributing to keeping total marketplace enrollment nearly stable despite unprecedented challenges.[15] Shrinking subsidies next year would likely lead to lower enrollment, especially among healthier people, compounding the damage from individual mandate repeal.

Of particular importance, using the savings from restoring CSR payments to pay for federal reinsurance funding — as House Republicans are reportedly contemplating — would be a harmful and unnecessary transfer of resources from people below 400 percent of the poverty line to people at higher income levels.[16] On their own, well-designed proposals for federal reinsurance funding would strengthen the individual market: by reimbursing insurers for some of the costs associated with high-cost enrollees, reinsurance allows them to charge lower premiums.[17] But because reinsurance lowers sticker price premiums, it only helps the minority of individual market consumers with incomes too high to qualify for subsidies — not those with incomes below 400 percent of the poverty level, who are eligible for premium tax credits. For consumers qualifying for tax credits, net premiums are determined based on their income, and the premium tax credits adjust automatically to make up the difference between the percentage of income the consumer is expected to pay for premiums and the sticker price. This means that, if a reinsurance program lowers sticker price premiums, premium tax credits will decline accordingly, and the amount subsidized consumers pay in net premiums will stay the same. These consumers would see no benefit from reinsurance, but would lose from reinstating CSR payments to offset a reinsurance program’s cost.

Restoring CSRs and using the resulting federal savings to fund reinsurance would thus entail cutting subsidies for people below 400 percent of the poverty line to pay for lowering premiums for people with incomes above those levels. Of course, many middle-income consumers also face challenges paying premiums. But assistance for these consumers should not come at the expense of people at lower income levels, who also face serious affordability challenges.

Stabilization legislation will also fail to achieve its goals if it ignores the greatest outstanding risk to the individual market: the Administration’s recent executive actions.

As of 2017, the ACA individual market was on track for greater price stability and competition going forward. After experiencing losses for 2014 through 2016 and increasing premium significantly for 2017, insurers were on track to break even or better on their individual market business, with recent data showing loss ratios in line with or lower than pre-ACA levels.[18] Marketplace enrollment remained robust despite the premium increases, with 12.2 million people signing up for 2017 plans (only slightly below the previous year).[19] And average 2017 individual market premiums were similar to average premiums for comparable employer market coverage, indicating that 2017 increases brought individual market premiums roughly in line with underlying market-wide health care costs.[20]

Absent policy changes, improving finances for insurers should have translated into slower premium growth for consumers in 2018, keeping individual market premiums in line with employer premiums.[21] Instead, policy actions and the uncertainty created by multiple attempts to repeal the ACA contributed to another year of high premium increases and insurer market exits.[22] The repeal of the individual mandate will likely result in additional premium increases in 2019 that also could have been avoided.

Yet even with the mandate repealed, the individual market is showing some positive signs for 2019. For example, Anthem, a major insurer that withdrew from a number of state markets last year, recently indicated that it is considering re-entering them, and Wellmark, a major Iowa insurer whose exit from Iowa’s market caused significant concern last year, has announced that it will re-enter, assuming there aren’t additional “significant changes to the Affordable Care Act.”[23] While premiums will be higher than they would have been without harmful policy actions, these statements point to continued market stability and suggest that consumer choice might even increase.

The Administration’s new rules threaten this progress. Most damaging to the individual market, the Administration is proposing to allow insurers to sell “short-term, limited duration” health plans lasting up to 364 days. Short-term plans are exempt from the ACA’s consumer protections, which means that these plans can deny coverage or charge higher premiums to people with pre-existing conditions; exclude essential health benefits such as maternity care, mental health and substance use treatment, and prescription drugs; and impose annual and lifetime limits on benefits. If finalized, the proposed rule would in effect allow a parallel insurance market — governed by pre-ACA rules — to operate alongside the ACA market, similar to the approach proposed by Senator Ted Cruz and rejected by Congress during the ACA repeal debate last year.[24]

The expansion of short-term plans will be harmful to some of the people who buy them, who then find themselves without coverage they need when they become seriously ill. But it will also harm people seeking comprehensive health plans in the ACA individual market. Because short-term plans can charge different rates based on health status and exclude the medical services needed by people with serious health conditions, they will be able to offer cheaper coverage to healthy people, pulling them out of the ACA risk pool. The Urban Institute estimates that the short-term plans rule will reduce the number of people purchasing comprehensive individual market coverage by 2.1 million, shrinking the ACA market in affected states by an average of almost 20 percent.[25] (See Figure 2.) Those dropping coverage will be healthier than average, raising average costs and premiums for those remaining in the ACA market.[26] This will make coverage less affordable — or unaffordable — for middle-income people with pre-existing conditions, for whom short-term plans won’t be a viable option, but who also aren’t eligible for marketplace subsidies that would shield them from premium increases.

Potentially even more damaging, the short-term plans rule significantly increases uncertainty about the individual market risk pool, making it more difficult for insurers to predict costs and set prices. While the Urban Institute’s analysis provides a best estimate of the number of people who will exit the ACA individual market in 2019, there is considerable uncertainty about how attractive short-term plans will be to consumers and how quickly the market for these plans will ramp up. Insurers will have to predict these outcomes for every market they participate in, while also forecasting how much healthier than average short-term plan enrollees will be. (This uncertainty comes on top of uncertainty created by repeal of the individual mandate.)

Under plausible assumptions, the short-term plans rule could raise average per-enrollee costs in the ACA market in the near term from less than 5 percent to 25 percent.[27] Faced with such substantial uncertainty — and the associated risk of substantial losses — some insurers may opt to protect themselves by pricing for the high end of the range, even if they expect costs will likely be lower. There is also a risk that some might decide to simply exit the ACA individual market until they see how things play out. As the Urban Institute study notes, “insurers will by necessity reexamine the profitability of remaining in the [ACA] compliant markets. This may well lead to more insurer exits from the compliant markets in the next years, reducing choice for the people remaining and ultimately making the markets difficult to maintain.” Even the Administration’s own analysis of the proposed rule raised this concern, noting “this proposed rule may further reduce choices for individuals remaining in [the] individual market single risk pool.”[28]

The Administration’s proposal to expand Association Health Plans (AHPs) would create similar problems, although the impact on the individual market likely would be smaller. As with the short-term plans proposed rule, the proposed AHP rule would give insurers more latitude to offer plans not subject to ACA rules, including to small businesses and self-employed individuals. While short-term plans are likely to be the more attractive options for healthy consumers seeking cheaper, limited-benefit plans, growth in AHPs may disrupt the individual market in states that have taken or take steps to prevent the expansion of short-term plans, or where associations aggressively recruit individual market enrollees. It may also disrupt states’ small group markets.[29] (Some provisions of the Administration’s proposed 2019 Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters, the annual rule updating provisions governing the ACA marketplaces, could also harm the individual market risk pool, for example by imposing new verification requirements that make it harder for consumers to maintain coverage.)

Any stabilization bill that fails to address the proposed expansion of non-ACA-compliant plans will leave the greatest new risk to the individual market untouched. Notably, simply providing reinsurance funding would not address the uncertainty and risk of insurer exits from the proposed short-term plans rule. While reinsurance relieves insurers of some of the costs associated with high-cost enrollees, to set premiums insurers still must be able to predict how many people — including how many healthier people — will enroll. Thus, a reinsurance program does not change the fact that insurers will be at risk of large losses if their assumptions about how many people (and how many healthy people) will leave the market in response to the expansion of short-term plans (or AHPs) prove too sanguine.

A final important principle for a stabilization package is simple: do no harm. Despite challenges, 11.8 million people signed up for 2018 coverage through the ACA marketplaces; millions more purchase comprehensive coverage subject to ACA rules and protections outside the marketplaces. More than 80 percent of marketplace consumers describe themselves as satisfied or very satisfied with their coverage, and many say it allows them to access critical health care they could not otherwise afford.[30] A stabilization package should not be an excuse to undo the coverage gains or improvements in coverage quality achieved under the ACA.

While the Alexander-Murray bill included various compromise provisions in addition to reinstating CSRs, and some elements raised concerns, these provisions retained the ACA’s core consumer protections and did not reduce coverage.[31] Now, however, some policymakers and outside interests are attempting to modify the Alexander-Murray and Collins-Nelson bills in ways that would violate those basic criteria.

In particular, policymakers should resist efforts to:

- Use reinsurance funding to open the door to high-risk pools. Some reinsurance proposals appear to let states use the federal reinsurance funds for high-risk pools, which segregate people with high-cost conditions into separate insurance markets or plans rather than pooling risks. That approach has a very poor track record: prior to the ACA, high-risk pools generally offered limited, unaffordable coverage or were not accessible to many people.[32] Other members of Congress have proposed letting states operate “invisible high-risk pools,” under which insurers are compensated for insuring people with high-cost conditions, rather than based on the actual costs of high-cost enrollees. In some cases (though not all), such programs require applicants to provide health status information before enrolling in coverage, creating barriers to signing up for plans.

- Use a stabilization bill as a vehicle to weaken consumer protections. For example, the Administration is reportedly arguing that a stabilization bill “must… include” changes allowing insurers to charge higher premiums to older adults and codify the expansion of short-term health plans.[33] The Administration and other policymakers are also seeking to use stabilization legislation as a vehicle for new, unrelated restrictions dealing with abortion services.

-

Offset the cost of federal reinsurance funding by making it harder for people to get health coverage. Some members of Congress have sought to pay for other health care policies by making it harder for people to obtain or maintain coverage through the ACA marketplaces. Last year, for example, House Republicans proposed to pay for extending funding for children’s health coverage and community health centers in part by shortening the “grace period” during which marketplace enrollees can catch up on past-due premiums, a change that would have caused up to 688,000 people to lose coverage.[34]

Not only would such proposals directly harm those affected, but some could undermine the goals of a stabilization bill. Policies that make it harder for people to enroll in coverage tend to disproportionately discourage healthier consumers, worsening the individual market risk pool and thus increasing premiums.

As discussed in the main text, many subsidized consumers will face higher costs if CSR payments are reinstated. How many consumers fall into this category depends on how many subsidy-eligible consumers will enroll in non-silver plans in 2019, assuming silver loading continues.

The best available proxy for that number comes from 2017 enrollment data. (2017 is the latest year for which the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has released detailed enrollment data by income and plan tier.[35] These data are only available for the 39 states using the HealthCare.gov eligibility and enrollment platform, and so this analysis is limited to these states, which account for about three-quarters of marketplace consumers.)

Nationwide, 1.6 million subsidized consumers, or 18 percent of all HealthCare.gov consumers, enrolled in non-silver plans (this was before the Administration’s decision not to pay CSRs increased silver plan premiums). This presumably represents a lower bound on the number of consumers who would enroll in non-silver plans once silver loading made doing so more advantageous. Another 1.7 million consumers with incomes between 200 and 400 percent of the poverty line selected silver plans in 2017, but would see lower premiums, cost sharing, or both as a result of silver loading if they switched to another metal tier. Adding these two groups together gives a total of 3.3 million consumers, or 36 percent of all HealthCare.gov consumers. This is an upper bound on those who benefit from silver loading and could lose if CSR payments were restored.

Consumers not included in these totals are:

- Subsidized consumers below 200 percent of the federal poverty line who enrolled in silver plans in 2017. Such consumers are generally better off remaining in silver plans and taking advantage of the cost-sharing assistance available to them in these plans. They pay neither more nor less under silver loading.

- Marketplace and off-marketplace consumers with incomes too high to qualify for subsidies. These consumers will pay more as a result of silver loading if they enroll in marketplace silver plans, but they can avoid these cost increases if they enroll in non-silver or — in most states — off-marketplace silver plans. Even in 2017, before silver loading, most unsubsidized consumers enrolled in coverage outside the marketplace, and the majority of unsubsidized marketplace consumers enrolled in a plan tier other than silver.

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| Based on Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2017 Plan Selection Data for HealthCare.gov States |

|---|

| |

Lower Bound on Number Facing Higher Costs |

|

Upper Bound on Number Facing Higher Costs |

|---|

| |

Subsidized Consumers Selecting Non-Silver Plans in 2017, Before Silver Loading |

As share of Marketplace Consumers |

Additional Consumers Who Could Benefit from Silver Loading if They Switch to Non-Silver Plan |

Total Number of Subsidized Consumers Potentially Benefiting from Silver Loading |

As share of Marketplace Consumers |

|---|

| Alaska |

8,499 |

44% |

2,903 |

11,402 |

60% |

| Alabama |

14,194 |

8% |

35,765 |

49,959 |

28% |

| Arkansas |

13,568 |

19% |

17,495 |

31,062 |

44% |

| Arizona** |

35,235 |

18% |

51,542 |

86,777 |

44% |

| Delaware** |

6,734 |

24% |

6,719 |

13,453 |

49% |

| Florida |

260,257 |

15% |

183,197 |

443,454 |

25% |

| Georgia |

59,323 |

12% |

72,541 |

131,864 |

27% |

| Hawaii** |

3,281 |

17% |

2,980 |

6,261 |

33% |

| Iowa |

11,390 |

22% |

13,698 |

25,088 |

49% |

| Illinois |

84,211 |

24% |

73,395 |

157,607 |

44% |

| Indiana** |

28,157 |

16% |

42,978 |

71,134 |

41% |

| Kansas |

23,458 |

24% |

15,536 |

38,994 |

39% |

| Kentucky |

13,958 |

17% |

22,496 |

36,454 |

45% |

| Louisiana |

32,059 |

22% |

27,507 |

59,566 |

41% |

| Maine |

17,781 |

22% |

18,178 |

35,958 |

45% |

| Michigan |

78,990 |

25% |

72,839 |

151,829 |

47% |

| Missouri** |

58,928 |

24% |

38,070 |

96,998 |

40% |

| Mississippi** |

8,190 |

9% |

11,548 |

19,738 |

22% |

| Montana** |

18,917 |

36% |

9,627 |

28,544 |

54% |

| North Carolina |

87,759 |

16% |

116,146 |

203,905 |

37% |

| North Dakota** |

7,066 |

32% |

4,921 |

11,987 |

55% |

| Nebraska |

23,485 |

28% |

17,397 |

40,882 |

48% |

| New Hampshire |

10,697 |

20% |

10,478 |

21,175 |

40% |

| New Jersey |

37,717 |

13% |

84,467 |

122,184 |

41% |

| New Mexico |

9,887 |

18% |

12,567 |

22,454 |

41% |

| Nevada |

19,271 |

22% |

18,786 |

38,057 |

43% |

| Ohio |

51,285 |

21% |

57,204 |

108,489 |

45% |

| Oklahoma** |

43,640 |

30% |

21,273 |

64,913 |

44% |

| Oregon |

37,460 |

24% |

38,307 |

75,767 |

49% |

| Pennsylvania |

48,916 |

11% |

127,234 |

176,150 |

41% |

| South Carolina |

17,697 |

8% |

52,575 |

70,272 |

31% |

| South Dakota** |

6,406 |

22% |

7,950 |

14,356 |

48% |

| Tennessee |

46,691 |

20% |

40,232 |

86,924 |

37% |

| Texas |

227,751 |

19% |

169,863 |

397,614 |

32% |

| Utah |

37,910 |

19% |

40,239 |

78,149 |

40% |

| Virginia |

64,556 |

16% |

75,951 |

140,507 |

34% |

| Wisconsin** |

50,085 |

21% |

49,793 |

99,878 |

41% |

| West Virginia** |

7,792 |

23% |

8,803 |

16,594 |

49% |

| Wyoming |

6,089 |

25% |

5,961 |

12,049 |

49% |

| HealthCare.gov total^ |

1,621,325 |

18% |

1,706,781 |

3,328,106 |

36% |