Cassidy-Graham Would Deeply Cut and Drastically Redistribute Health Coverage Funding Among States

Senators Bill Cassidy and Lindsey Graham are reportedly working with the White House to push their plan to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA).[1] The Cassidy-Graham plan (which Senator Dean Heller has also co-sponsored) would have much the same damaging consequences as other Senate and House Republican repeal and replace bills. It would cause many millions of people to lose coverage, radically restructure and deeply cut Medicaid, increase out-of-pocket costs for individual market consumers, and weaken or eliminate protections for people with pre-existing conditions.

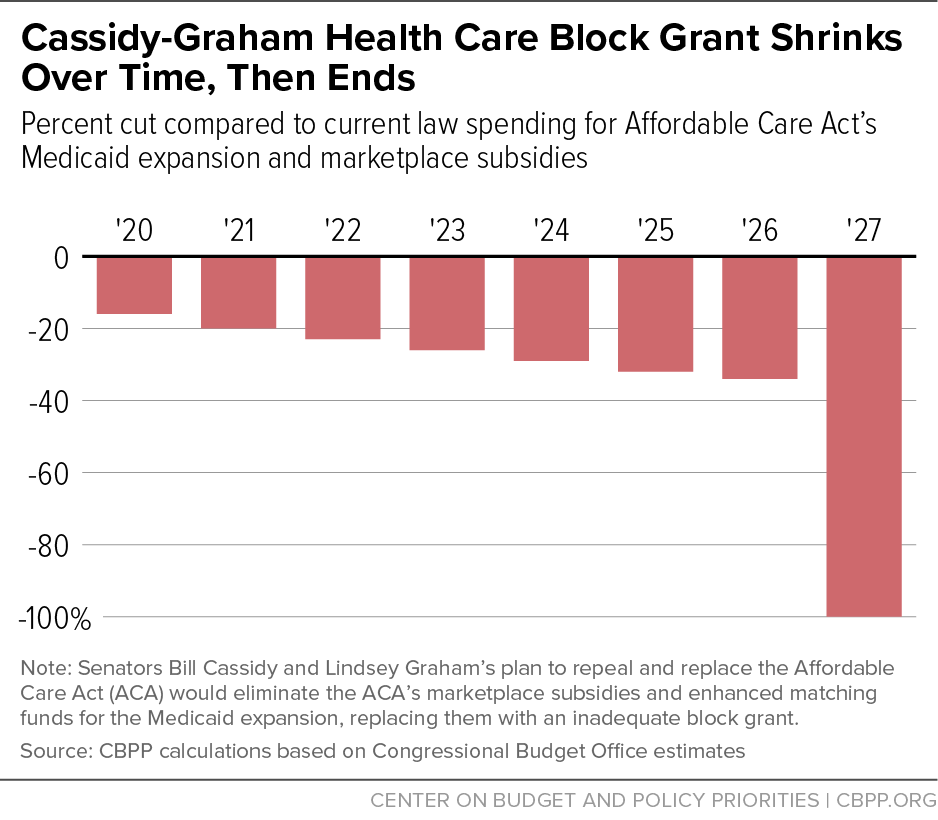

That’s because the plan would eliminate the ACA’s marketplace subsidies and enhanced matching rate for the Medicaid expansion, replacing them with an inadequate block grant whose funding would shrink further over time (compared to current spending levels) and then disappear altogether after 2026. The plan would also convert Medicaid’s current federal-state financial partnership to a per capita cap, which would cap and cut federal Medicaid per-beneficiary funding for seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children. Finally, it would allow states to waive ACA provisions that prohibit health insurance plans from placing annual or lifetime limits on coverage and require them to cover key services.

All states would eventually face deep and growing cuts to federal coverage programs due to the plan’s radical structural changes to these programs, which would make federal funding far less responsive to need. But some states would suffer immediate, disproportionate harm because the block grant would not only cut overall funding for the Medicaid expansion and marketplace subsidies but also redistribute the sharply reduced federal funding across states, based largely on criteria unrelated to states’ actual spending needs and the coverage gains they’ve achieved under the ACA.

In general, the plan would effectively punish states that have been especially successful at enrolling low- and moderate-income people in the Medicaid expansion or in marketplace coverage under the ACA, while imposing less damaging cuts, or even initially increasing funding, for states that have rejected the Medicaid expansion, enrolled fewer people in marketplace coverage, and have lower population density and lower per-capita income. The cuts would be especially severe in nine states — California, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, and Virginia, plus the District of Columbia. By 2026, block grant funding amounts in these states would be 50 percent or less of the federal Medicaid expansion and/or marketplace subsidy funding these states would otherwise receive.

And that’s not even accounting for the additional, substantial Medicaid cuts all states would face due to the Cassidy-Graham plan’s per capita cap in that year. According to our estimates, by 2026 — the year before the plan’s block grant funding would end altogether — 42 states and the District of Columbia would see net cuts in federal health coverage funding due to the combined effect of the plan’s block grant and its Medicaid per capita cap.

Cassidy-Graham Proposal Shifts Costs and Risks to States

The Cassidy-Graham plan would eliminate enhanced funding for the Medicaid expansion and the marketplace subsidies (as well as funding for the Basic Health Program[2] in the two states that have implemented it) and replace them with a block grant that states could use not only for health coverage but also for other health care purposes. Cassidy-Graham would establish an annual overall block grant amount for each year from 2020 through 2026. The block grant would equal $140 billion in 2020, which is $26 billion, or 16 percent, below projected federal spending for the Medicaid expansion and marketplace subsidies under current law. The block grant would increase annually by roughly 2 percent, to $158 billion in 2026. That wouldn’t even keep pace with general inflation, which the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects to equal 2.4 percent annually over that period, let alone with expected growth in per-beneficiary health care costs and enrollment.[3] Thus, by 2026, block grant funding under the plan would be $83 billion, or 34 percent, below currently projected federal spending on the ACA’s major coverage expansions.[4] (See Figure 1.)

Cassidy-Graham would eliminate the block grant entirely after 2026, meaning that in 2027 and beyond, there would be zero funding available to replace states’ Medicaid expansions and marketplace tax credits and cost-sharing reductions. As a result, states would face a severe funding cliff that would leave states with no federal resources to continue to provide coverage for their low- and moderate-income residents who’ve gained coverage under the ACA’s coverage expansions.

These cuts would be on top of the damaging cuts that would result from the Medicaid per capita cap from the Senate Republican leadership bill (the Better Care Reconciliation Act), which the Cassidy-Graham plan fully incorporates. (See Figure 2.) The Senate bill’s Medicaid cuts, outside of the Medicaid expansion, would equal $180 billion over ten years, CBO estimates. The cuts resulting from the per capita cap would increase rapidly over time, reaching $41 billion annually by 2026: a nearly 9 percent cut to total federal Medicaid spending for seniors, people with disabilities, families with children, and other adults (outside of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion) in that year. These large and growing cuts from the per capita cap are the primary reason CBO expects the Senate bill’s total Medicaid cuts to increase rapidly after 2026 (when the Cassidy-Graham block grant would expire), rising from a 26 percent cut to total federal Medicaid spending in 2026 to a 35 percent cut by 2036, relative to current law.[5]

Moreover, these estimates underestimate the actual cuts to federal funding for health coverage because they don’t include the structural impact of converting federal funding for the Medicaid expansion and marketplace subsidies into a block grant and converting federal funding for the rest of the Medicaid program to a per capita cap. Under current law, federal funding for the Medicaid expansion and marketplace subsidies automatically adjusts to account for increases in enrollment or health care costs. In contrast, the Cassidy-Graham block grant amounts would be fixed, no longer adjusting for increased enrollment due to recessions or higher costs related to public health emergencies, new breakthrough treatments, demographic changes, or other cost pressures. Faced with a recession, for example, states would have to either dramatically increase their own spending on health care or, as is far more likely, deny help to people losing their jobs and their health insurance.[6] Likewise, under the Medicaid per capita cap, federal Medicaid funding for seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children would no longer automatically increase to account for higher per-beneficiary costs such as prescription drug price spikes or rising costs resulting from an aging population. States would be responsible for 100 percent of all costs above the cap.

Finally, the Cassidy-Graham plan includes other harmful changes. In particular, the proposal includes provisions of the Senate Republican leadership bill that would allow states to waive important consumer protections in the individual market. Under these waivers, which would be subject to near-automatic approval by the federal government, insurers could exclude crucial services such as maternity and mental health care from their plans, impose annual and lifetime limits, and dramatically raise deductibles and other out-of-pocket costs. According to CBO, states with about half of the population would take up these damaging waivers. In addition, Senators Cassidy and Graham are reportedly also considering adding to their plan the so-called “Cruz amendment,” which would allow insurers to charge sharply higher premiums to people with pre-existing conditions or deny them coverage altogether.[7]

Cassidy-Graham Plan Would Hit Certain States Especially Hard

Under the Cassidy-Graham plan, each year’s total block grant amount would be allocated among the states based on a complex formula that incorporates several factors. It would not be tied to actual federal spending on the Medicaid expansion and/or marketplace subsidies for residents of a state. Thirty percent of the total block grant amount would be made available to all states and the District of Columbia. But only some states that meet certain criteria would qualify for the remaining 70 percent of the already inadequate pool of federal funding. The annual block grant amount would be allocated in the following ways (also see Table 1):

- 30 percent to all states. 20 percent would be allocated based on states’ share of the national population aged 45 to 64, presumably in 2019. 10 percent would allocated based on states’ share of the national population between 100 percent and 138 percent of the federal poverty line in 2019.

- 35 percent to ACA Medicaid expansion states. Allocations would be based on the share of expansion states’ total population in 2016 between 100 percent and 138 percent of poverty (even though the Medicaid expansion also covers people in poverty).

- 25 percent to states with per capita income below $52,500 in 2016. Allocations would be based on the share of the total population of such states in 2019 between 100 percent and 138 percent of the federal poverty line.

- 10 percent to states with low population density. Low population density is defined as having no more than 114 people per square mile in 2016. Amounts would be allocated evenly among states that qualify within each of three categories of low population density.

| TABLE 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distribution of Cassidy-Graham Block Grant | ||||

| Factor | Qualifying states | Share of total block grant | Fiscal year 2020 block grant amount | Distribution criteria |

| 45- to 64-year-olds | All states | 20% | $28 billion | State share of national population aged 45 to 64 |

| Low-income population | All states | 10% | $14 billion | State share of national population with incomes between 100% and 138% of poverty line |

| Medicaid expansion | Medicaid expansion states (32 states) | 35% | $49 billion | State share of expansion states’ total population with incomes between 100% and 138% of poverty line |

| Lower per capita income | Per capita income <$52,500 (38 states) |

25% | $35 billion | State share of qualifying states’ total population with incomes between 100% and 138% of poverty line |

| Low population density | ||||

| Category 1 | < 15 persons per square mile (5 states) | 1% | $1.4 billion | Distributed evenly among qualifying states in category |

| Category 2 | 15 to 79 persons per square mile (17 states) | 3.5% | $4.9 billion | Distributed evenly among qualifying states in category |

| Category 3 | 80 to 114 persons per square mile (7 states) | 5.5% | $7.7 billion | Distributed evenly among qualifying states in category |

Source: Congressional Record.

The Cassidy-Graham proposal’s block grant allocation formula would thus not only deeply cut overall funding for Medicaid expansion and marketplace subsidies but also drastically redistribute current federal funding for the ACA’s major coverage expansions across states. In general:

- States that have expanded Medicaid would receive a smaller share of federal funding, relative to what they’d receive under current law. This will result in expansion states losing funds to non-expansion states. The Cassidy-Graham plan thus forces a zero-sum tradeoff by capping total federal support for coverage and redistributing funds from expansion states to those that haven’t expanded. In contrast, under current law, non-expansion states can choose to take up the expansion at any time and draw down additional enhanced federal Medicaid funds that would not come at other states’ expense.

- States with greater use of marketplace subsidies among eligible individuals would lose federal funding to states with lower take-up of subsidies, largely because the formula relies on proportional shares based on states’ near-poor and near-elderly populations. This is a key reason why Florida and North Carolina, both of which have unusually high marketplace subsidy take-up rates, would face disproportionately large cuts under the block grant, even though they haven’t expanded Medicaid.[8]

- States with higher per capita income would lose federal funding to lower-income states, even though some states with higher average income have a relatively large share of low-income residents.

- More densely populated states would lose federal funding to less densely populated states. In addition, the specific population density thresholds used in the proposal are arbitrary — thresholds of 15, 79, and 114 persons per square mile — with the only apparent rationale being to include or exclude particular states from the categories.

The result of this complex formula is that certain states would face disproportionately large cuts due to the block grant, which would become even more severe as the overall block grant funding grows increasingly inadequate each year. For example, according to our estimates, the following states would see cuts of 50 percent or more to federal funding for the Medicaid expansion and/or marketplace subsidies in 2026, relative to current law: California, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, and Virginia, plus the District of Columbia. New York would see an estimated cut of 70 percent in 2026, relative to current law.

Federal funding for some states would rise under the Cassidy-Graham block grant, relative to current law, at least initially. But focusing on those increases ignores the damaging cuts from the Medicaid per capita cap, which would take effect in 2020. We estimate that the combined effect of the block grant and the Medicaid per capita cap would result in 42 states and the District of Columbia facing net cuts to federal funding for Medicaid (not just the expansion) and marketplace subsidies by 2026. (See Appendix Table 1.)

Of course, all states would see very large, damaging cuts in federal funding for health coverage starting in 2027, when the Cassidy-Graham plan completely eliminates the block grant. Moreover, as discussed above, these estimates do not take into account the increased risk of additional cuts that all states would face as a result of radically restructuring federal funding, which now automatically adjusts based on actual spending needs, into either a block grant or per capita cap that would provide states fixed funding even if costs rise faster than anticipated. So even the handful of states that wouldn’t see federal funding cuts through 2026 if costs grew as anticipated would still be at substantial risk of cuts, and would be likely to face federal funding cuts (relative to current law) if there were unexpected increases in enrollment and/or per-enrollee health costs.

Methods Note

We estimate each state’s federal funding block grant amount in 2026 under the parameters of the Cassidy-Graham block grant formula, and compare the result to an estimate of the state’s federal funding under current law for the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion to low-income adults, marketplace subsidies, and/or the Basic Health Program (BHP).

To estimate states’ Cassidy-Graham block grant amounts in 2026, we use the most recent per capita income data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, population density data from the Census Bureau, and population data for those aged 45 to 64 years from the American Community Survey.

To estimate states’ federal funding under current law, we start with the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) March 2016 projections of national-level spending on the Medicaid expansion, marketplace subsidies, and the BHP in 2026. We apportion these amounts across the states based on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ most recent state-level Medicaid expansion and marketplace subsidies spending data.

Results of our analysis reflect two limitations. First, limited data availability requires that we apportion CBO’s national-level estimate of cost-sharing reduction payments to states based on states’ premium tax credit amounts rather than cost-sharing reduction amounts. Second, CBO’s projection of Medicaid expansion spending in 2026 assumes that additional states beyond the current 31 states and the District of Columbia take up the option to expand Medicaid, but CBO does not project which specific states would do so.

Results in the appendix table reflect the combined impact of the Cassidy-Graham block grant and the Medicaid per capita cap in the Senate GOP leadership’s health bill, the Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA). The CBO estimates the federal Medicaid funding cut outside of the expansion, due to the per capita cap, in its BCRA cost estimate. We apportion this national cut estimate in 2026 to states based on the Kaiser Family Foundation’s state-specific estimates of the federal funding impact of the BCRA’s per capita cap.

| APPENDIX TABLE 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cassidy-Graham Block Grant and Medicaid Per Capita Cap Cuts Federal Funding for Most States by 2026 | |||

| State | Estimated federal funding change, in 2026 (in $millions) | ||

| United States | -$124,000 | ||

| Alabama | 923 | ||

| Alaska | - 149 | ||

| Arizona | - 1,550 | ||

| Arkansas | - 1,057 | ||

| California | - 35,177 | ||

| Colorado | - 329 | ||

| Connecticut | - 2,476 | ||

| Delaware | - 725 | ||

| District of Columbia | - 556 | ||

| Florida | - 9,668 | ||

| Georgia | - 1,995 | ||

| Hawaii | - 619 | ||

| Idaho | - 33 | ||

| Illinois | - 1,309 | ||

| Indiana | - 454 | ||

| Iowa | - 114 | ||

| Kansas | 373 | ||

| Kentucky | - 2,150 | ||

| Louisiana | - 2,316 | ||

| Maine | - 180 | ||

| Maryland | - 2,607 | ||

| Massachusetts | - 5,769 | ||

| Michigan | - 3,402 | ||

| Minnesota | - 2,143 | ||

| Mississippi | 339 | ||

| Missouri | - 94 | ||

| Montana | - 307 | ||

| Nebraska | 13 | ||

| Nevada | - 257 | ||

| New Hampshire | - 446 | ||

| New Jersey | - 4,694 | ||

| New Mexico | - 1,262 | ||

| New York | - 22,018 | ||

| North Carolina | - 4,738 | ||

| North Dakota | - 52 | ||

| Ohio | - 2,603 | ||

| Oklahoma | 64 | ||

| Oregon | - 3,267 | ||

| Pennsylvania | - 525 | ||

| Rhode Island | - 665 | ||

| South Carolina | - 943 | ||

| South Dakota | 294 | ||

| Tennessee | - 716 | ||

| Texas | - 565 | ||

| Utah | - 101 | ||

| Vermont | - 192 | ||

| Virginia | - 2,504 | ||

| Washington | - 2,991 | ||

| West Virginia | - 284 | ||

| Wisconsin | 214 | ||

| Wyoming | 22 | ||

Source: CBPP analysis, see methods notes for details.

End Notes

[1] Sarah Kliff, “The last GOP health plan left standing, explained,” Vox, August 1, 2017, https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/8/1/16074746/Graham-Cassidy-obamacare-repeal.

[2] Under the Basic Health Program (BHP), states may elect to establish their own health coverage program for individuals with incomes up to 200 percent of the federal poverty line who would otherwise obtain coverage through the marketplaces. States operating a BHP are eligible to receive federal funding equal to 95 percent of the marketplace subsidies that otherwise would have been spent for BHP enrollees. Two states — Minnesota and New York — operate BHPs.

[3] Congressional Budget Office, “H.R. 1628: Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017,” June 26, 2017, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/52849-hr1628senate.pdf.

[4] “Senate Amendment 586 to H.R. 1628,” https://www.congress.gov/amendment/115th-congress/senate-amendment/586/text.

[5] Congressional Budget Office, “Longer-Term Effects of the Better Care Reconciliation Act of 2017 on Medicaid Spending,” June 2017, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/52859-medicaid.pdf.

[6] For additional discussion of these issues, see Judith Solomon et al., “Cassidy-Graham Amendment Would Cut Hundreds of Billions from Coverage Programs, Cause Millions to Lose Health Insurance,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 27, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/cassidy-graham-amendment-would-cut-hundreds-of-billions-from-coverage-programs-cause.

[7] https://twitter.com/Emma_Dumain/status/892874093766336514. For an explanation of the so-called “Cruz amendment,” see Sarah Lueck, “Cruz Amendment Would Worsen Already Harmful Senate Health Bill for People with Medical Conditions,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 12, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/cruz-amendment-would-worsen-already-harmful-senate-health-bill-for-people-with.

[8] Matthew Buettgens, Genevieve M. Kenney, and Clare Pan, “Variation in Marketplace Enrollment Rates in 2015 by State and Income,” Urban Institute, October 2015, http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2015/rwjf424382.

More from the Authors