End Notes

[1] “How Past Crimes May Drive Job Seekers Into Poverty,” PBS NewsHour, January 23, 2015.

[2] Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Prisoners in Custody of State or Federal Correctional Authorities, 1997-98,” March 9, 2015; Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Prisoners Series,” 2000-2014, http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbse&sid=40.

[3] M. Sickmund, T.J. Sladky, W. Kang, and C. Puzzanchera, “Easy Access to the Census of Juveniles in Residential Placement," National Center for Juvenile Justice, 2013, http://www.ojjdp.gov/ojstatbb/ezacjrp/.

[4] Lauren E. Glaze and Danielle Kaeble, “Correctional Populations in the United States, 2013,” Department of Justice, December 2014.

[5] Peter Wagner, Leah Sakala, and Josh Begley, “States of Incarceration: The Global Context,”Prison Policy Initiative, June 2014; Jan van Dijk, John van Kesteren, and Paul Smith, Criminal Victimisation in International Perspective: Key Findings From the 2004-2005 ICVS and EU ICS (The Hague: Book Juridische uitgevers, 2007).

[6] As of December 31, 2013, 4,751,400 people were on probation or parole; Glaze and Kaeble, “Correctional Populations in the United States, 2013.”

[7] Justice Policy Institute, “Poor Prescription: The Costs of Imprisoning Drug Offenders in the United States,” 2001; Brennan Center for Justice, “Reforming Funding to Reduce Mass Incarceration,” 2013.

[8] T. Bonczar, “Prevalence of Imprisonment in the U.S. Population, 1974-2001,” Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2003.

[9] American Civil Liberties Union, The War on Marijuana in Black and White, 2012.

[10] Washington Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs, “Racial Disparities in Arrests in the District of Columbia, 2009-2011: Implications for Civil Rights and Criminal Justice in the Nation’s Capital,” 2013. Since non-African Americans make up the majority of D.C. residents, and drug use rates between different groups are about the same, most drug users are likely to be white or non-African American. See also Rend Smith, “Race Disparity in Drug Charges Is Getting Worse,” Washington City Paper, April 22, 2013.

[11] Leah Sakala, “Paying the Price of Mass Incarceration,” Prison Policy Initiative, 2014, http://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2014/05/23/price-of-incarceration/).

[12] Tracey Kyckelhahn, “Justice Expenditure and Employment Extracts, 2012—Preliminary,” NCJ 248628,Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2015.

[13] Robert Jesse Willhide, “Annual Survey of Public Employment and Payroll Summary Report: 2013,” U.S. Census Bureau, 2014.

[14] Alfred Blumstein, ed., The Crime Drop in America (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

[15] Michael Mitchell and Michael Leachman, “Changing Priorities: State Criminal Justice Reforms and Investments in Education,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 2014, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=4220.

[16] Brennan Center for Justice, “What Caused the Crime Decline?” 2015.

[17] According to a Bureau of Justice Statistics survey of state criminal record repositions, in 2012 there were 100,596,300 subjects (“individual offenders”) in state systems with an arrest or conviction for a serious misdemeanor or felony (Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Survey of State Criminal History Information Systems, 2012,” January 2014, p. 2). To account for duplication of individual records in the survey of the state criminal record repositories (that is, individuals who may have criminal records in more than one state and deceased individuals who have not been removed from the state record systems), NELP conservatively reduced the number of individuals by 30 percent to arrive at a total of 70,417,410 individuals with state arrest or conviction records. The U.S. Census 2012 population estimate for those 18 years and over was 240,185,952 (U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, “Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States and States, April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012, June 2013). Based on these estimates, 29.3 percent of U.S. adults, or nearly one in three, have a criminal history on file with the states.

[18] Binyamin Appelbaum, “The Vanishing Male Worker: How America Fell Behind,” New York Times, December 11, 2014; Binyamin Appelbaum, “Out of Trouble, Out of Work,” New York Times, March 1, 2015.

[19] John Schmitt and Kris Warner, “Ex-Offenders and the Labor Market,” Center for Economic and Policy Research, 2010; Christopher Uggen, Jeff Manza, and Melissa Thompson, “Citizenship and Reintegration: The Socioeconomic, Familial, and Civic Lives of Criminal Offenders,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 605 (May 2006), pp. 281-310.

[20] Sarah Shannon, Christopher Uggen, Melissa Thompson, Jason Schnittker, and Michael Massoglia, “The Growth in the U.S. Ex-Felon and Ex-Prisoner Population, 1948 to 2010,” Princeton University, 2011, http://paa2011.princeton.edu/papers/111687); Appelbaum, “Out of Trouble, Out of Work.”

[21] Society for Human Resources Management, “Background Checking: The Use of Criminal Background Checks in Hiring Decisions,” 2012.

[22] Ibid.; see also EmployeeScreenIQ, “Survey Report 2013: Employment Screening Practices and Trends: The Era of Heightened Care and Diligence,” 2013, p. 10.

[23] In fact, the probability of being arrested is no greater for an individual who has been previously arrested for a crime compared to an individual in the general population, if the individual has not been arrested for three to seven years. The variation in the “redemption times” is dependent on the state and the nature of the individual’s previous offense (four to seven years for violent crimes, four years for drug crimes, three to four years for property crimes); Alfred Blumstein and Nakamura Kiminori Nakamura, “Extension of Current Estimates of Redemption Times: Robust Testing, Out-of-State Arrests, and Racial Differences,” National Institute of Justice, October 2012, p. 89.

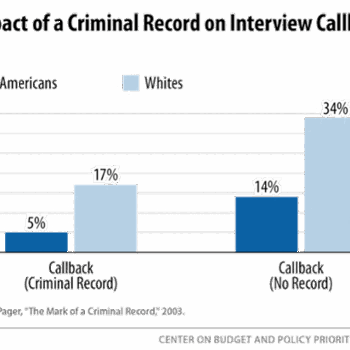

[24] Devah Pager, “The Mark of a Criminal Record,” American Journal of Sociology 108 (5) (2003), pp. 937-75; Scott Decker, Cassia Spohn, Natalie Ortiz, and Eric Hedberg, “Criminal Stigma, Gender, and Employment: An Expanded Assessment of the Consequences of Imprisonment for Employment,” U.S. Department of Justice, January 2014.

[25] This input to growth is also one reason why CBO scores comprehensive immigration reform as pro-growth: Reform is expected to boost the increase of labor supply, and thus GDP growth. These concerns have become particularly germane in recent years as the U.S. labor force participation rate fell sharply in the recession and weak recovery. It has recently stabilized, but at a historically low level. Some of that decline is reasonably assigned to demographic factors, largely baby boomers aging out of the workforce. But as the President’s Council of Economic Advisors has pointed out, about half of the decline is due to cyclical (weak demand) and structural factors, including the steep incarceration of young minority men (CBO, “The Slow Recovery of the Labor Market,” February 2014, Figure 11; CBO, “The Economic Impact of S.744, The Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act,” June 2013; CEA, “The Labor Force Participation Rate Since 2007: Cause and Policy Implications,” July 2014).

[26] Schmitt and Warner, “Ex-Offenders and the Labor Market.”

[27] Bruce Western and Becky Petit, “Collateral Costs: Incarceration’s Effect on Economic Mobility,” Pew Charitable Trust, 2010.

[28] Marc Schindler, Amanda Petteruti, and Jason Ziedenberg, “Sticker Shock: Calculating the Full Price for Youth Incarceration,” Justice Policy Institute, 2014.

[29] Pager, “The Mark of a Criminal Record.”

[30] Schmitt and Warner, “Ex-Offenders and the Labor Market.”

[31] Carl Hulse, “Unlikely Cause Unites the Left and Right: Justice Reform,” New York Times, February 18, 2015; Michael Hirsh, “Charles Koch, Liberal Crusader,” Politico, March/April 2015.

[32] Examples of bipartisan criminal justice reform legislation being considered in the 114th Congress include the Corrections Oversight, Recidivism Reduction, and Eliminating Costs for Taxpayers in Our National System (CORRECTIONS) Act (S. 467), the Record Expungement Designed to Enhance Employment (REDEEM) Act (S. 2567), the Justice Safety Valve Act (S. 619), and the Smarter Sentencing Act (S. 502).

[33] Sentencing Project, “The State of Sentencing 2014: Developments in Policy and Practice,” 2015.

[34] Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice, “Proposition 47: Estimated Local Savings and Job Population Reductions,” September 2014.

[35] Center for Health and Justice, Treatment Alternatives for Safe Communities, “No Entry: A National Survey of Criminal Justice Diversion Programs and Initiatives,” 2013.

[36] Dick Mendel, “No Place for Kids,” Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2011.

[37] National Council on Crime and Delinquency, “Using Bills and Budgets to Further Reduce Youth Incarceration,” 2013.

[38] U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, “EEOC Enforcement Guidance: Consideration of Arrest and Conviction Records in Employment Decisions Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,” April 25, 2012.

[39] EmployeeScreenIQ, “Survey Report 2013,” pp. 15-16.

[40] The White House, “My Brother’s Keeper Task Force Report to the President,” May 2014, p. 10.

[41] Christopher Uggen, Mike Vuolo, Sarah Lageson, Ebony Ruhland, and Hilary K. Whiteman, “The Edge of Stigma: An Experimental Audit of the Effects of Low-Level Criminal Records on Employment,” Criminology 52 (4) (2014), p. 650.

[42] Maurice Emsellem and Michelle Rodriguez, “Advancing a Federal Fair Chance Hiring Agenda: Background Check Reforms in Over 100 Cities, Counties, and States Pave the Way for Federal Action,” National Employment Law Project, January 2015, p. 6.

[43] Editorial, “Remove Unfair Barriers to Employment,” New York Times, February 28, 2015; Emsellem, “Advancing a Federal Fair Chance Hiring Agenda”; Rebecca Vallas and Sharon Dietrich, “One Strike and You’re Out; How We Can Eliminate Barriers to Economic Security and Mobility for People With Criminal Records,” Center for American Progress, December 2014, p. 35; All of Us or None, PICO National Network, “Formerly Incarcerated People Request an Executive Order to ‘Ban the Box,’” September 2014; PICO National Network, “Fulfilling the Promise of My Brother’s Keeper,” June 2014.

[44] National Consumer Law Center, “Broken Records: How Errors by Criminal Background Checking Companies Harm Workers and Businesses,” April 2012; National Employment Law Project and Center for Community Change, “Wild West of Criminal Background Checks for Employment,” August 2014.

[45] For example, the Federal Trade Commission settled a $2.6 million case against HireRight Solutions, one of the nation’s largest background check companies, for failing to ensure the accuracy of the reports as required by FCRA. Editorial, “Accuracy in Criminal Background Checks,” New York Times, August 9, 2012; “Background-Check Industry Under Scrutiny as Profits Soar,” Crain’s New York Business, June 23, 2013.

[46] Madeline Neighly and Maurice Emsellem, “Wanted: Accurate FBI Background Checks for Employment,” National Employment Law Project, 2013.

[47] Marc Levin and Vikrant Reddy, “The Verdict on Federal Prison Reform: State Successes Offer Keys to Reducing Crime and Costs,” Texas Public Policy Foundation, July 2013, p. 6.

[48] Morris Kleiner, “Reforming Occupational Licensing Policies,” Hamilton Project, January 2015.

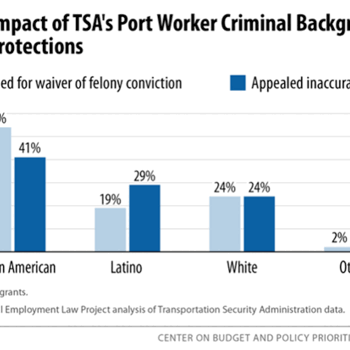

[49] Maritime Transportation Security Act, 42 U.S.C. Section 70105.

[50] National Employment Law Project, “A Scorecard on the Post-9/11 Port Worker Background Checks,” July 2009.

[51] Ram Subramanian and Rebecca Moreno, “Relief in Sight? States Rethink Collateral Consequences of Criminal Conviction, 2009-2014,” Vera Institute for Justice, 2014.