The share of eligible families that participate in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) has declined over the past decade, and the reach of this critical program appears to have declined further during the pandemic. WIC provides nutritious foods, nutrition education, breastfeeding support, and referrals to health care and social services to low-income pregnant and postpartum people, infants, and children under age 5. A large body of research demonstrates that WIC improves participants’ health, developmental, and nutrition outcomes.[1]

Since the start of the COVID-19 health and economic crisis, the number of individuals eligible for WIC has likely grown substantially. And, with an increase in need, one would expect WIC participation to have grown substantially as well. Yet WIC participation — that is, the number of individuals enrolled in WIC and receiving benefits — increased by only 2 percent between February 2020 and February 2021, a year into the pandemic.[2]

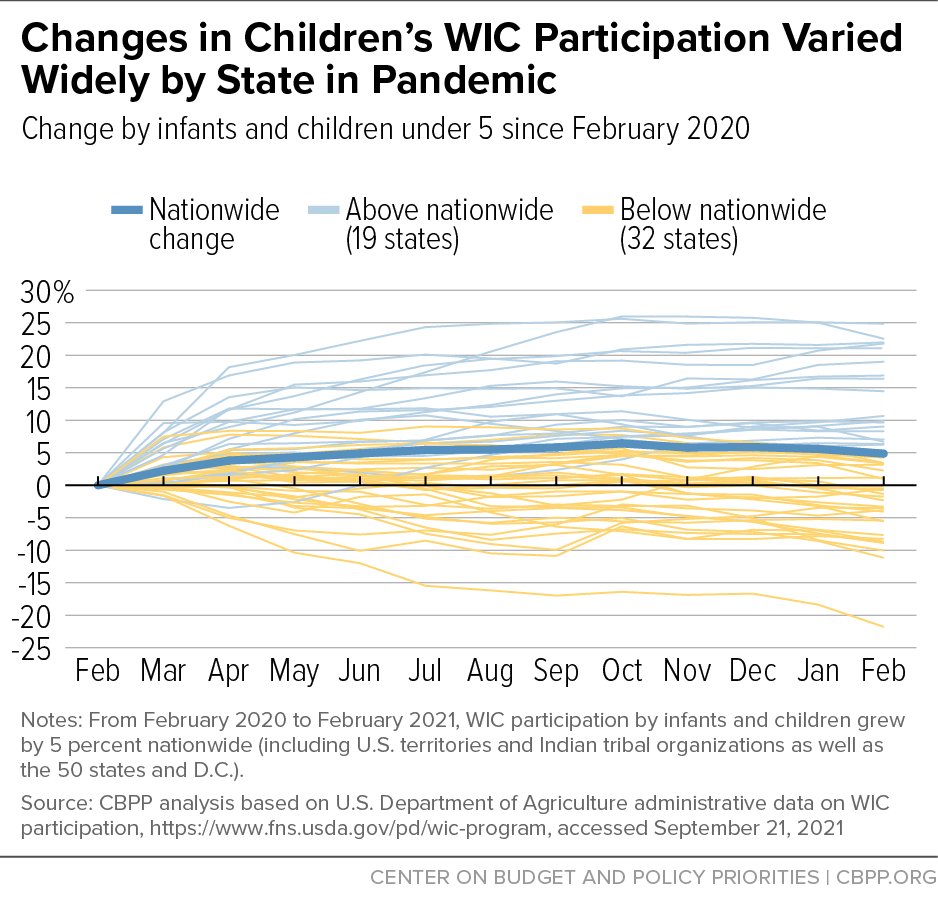

Participation changes over this period varied widely across states, ranging from a 20 percent increase to a 21 percent decrease. States with substantial increases may be reaching a greater share of eligible individuals than before the pandemic, which could illuminate policies and practices that appeal to potential participants. On the other hand, in 31 states WIC grew by less than the nationwide average of 2 percent or declined.[3] In these states, the decline in the share of eligible individuals benefitting from WIC likely accelerated, with substantial numbers of eligible low-income families missing out on WIC’s proven benefits.

Comparing WIC participation data to Medicaid and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) participation can shed further light on the extent to which WIC is reaching eligible individuals because Medicaid and SNAP participants are automatically income-eligible for WIC.[4] Though gaps in the publicly available data preclude an ideal comparison, we can glean some important lessons, and state officials — who have access to more nuanced participation data — can measure the extent to which WIC is not reaching eligible families and conduct targeted outreach to families participating in Medicaid or SNAP but not WIC.

Even before the pandemic, a substantial share of Medicaid and SNAP participants who were income-eligible for WIC were not enrolled. Pilot projects conducted in four states during 2018 and 2019 found that between 44 percent and 63 percent of WIC-eligible people enrolled in Medicaid or SNAP were not enrolled in WIC. Recent trends suggest the gap may be even larger today.

Two factors have driven a steady increase in Medicaid enrollment since the start of the pandemic. First, as a result of the economic crisis, unemployment soared; as income dropped and families lost employer-provided health insurance, more families with children qualified for Medicaid. Second, the “continuous coverage” provision established by the Families First Coronavirus Response Act prevents states from terminating Medicaid coverage except under very narrow circumstances, so that low-income individuals can continue receiving health care benefits during the public health emergency.[5] This policy removes procedural barriers that typically cause many eligible families to cycle on and off Medicaid, so more of the families eligible for Medicaid are likely enrolled now. In addition, some individuals are continuing to receive Medicaid who otherwise would have become ineligible or lost benefits, as this policy permits.

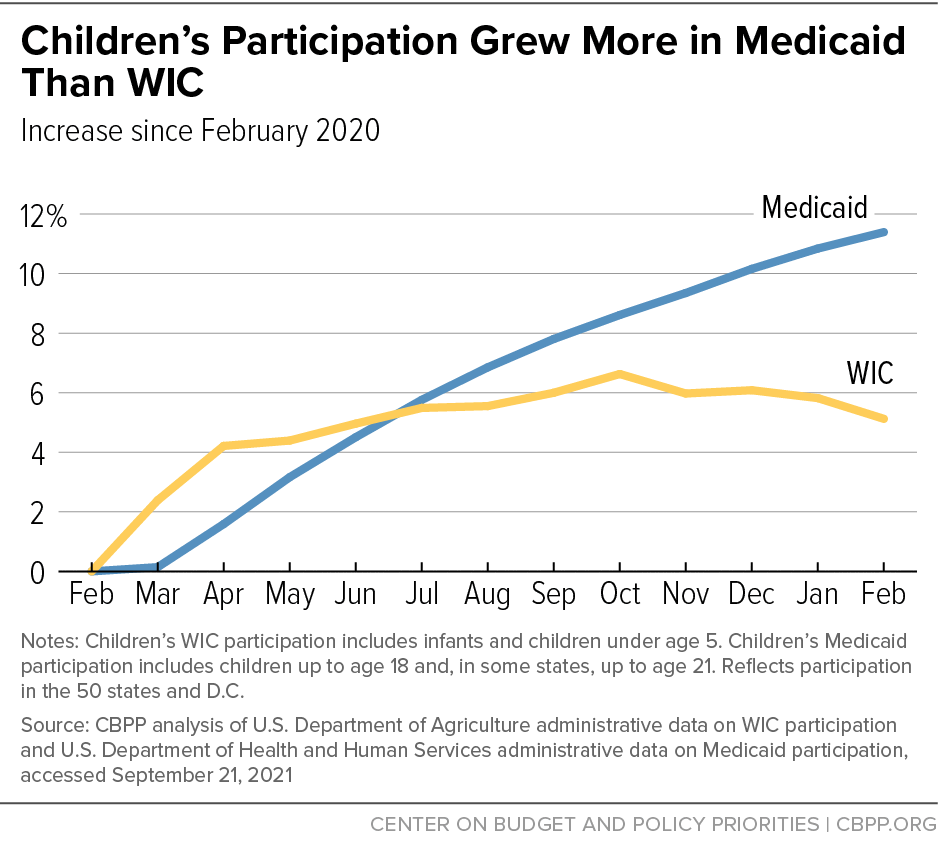

In the 50 states and D.C., Medicaid enrollment increased by 16 percent between February 2020 and February 2021, while WIC participation grew by just 3 percent. Because Medicaid — unlike WIC — serves families with older children as well as seniors and individuals without children at home, it is helpful to focus on enrollment by children where data are available. Here, too, Medicaid growth outpaced WIC. In the 50 states and D.C., Medicaid enrollment of children increased by 11 percent from February 2020 to February 2021, while nationwide WIC participation by infants and young children increased by 5 percent from February 2020 to February 2021.[6] Continuous coverage likely enables Medicaid to serve a higher share of eligible children than it otherwise would, so current Medicaid enrollment (as opposed to enrollment before the policy took effect) may provide a more accurate picture of the number of children whom WIC could serve.

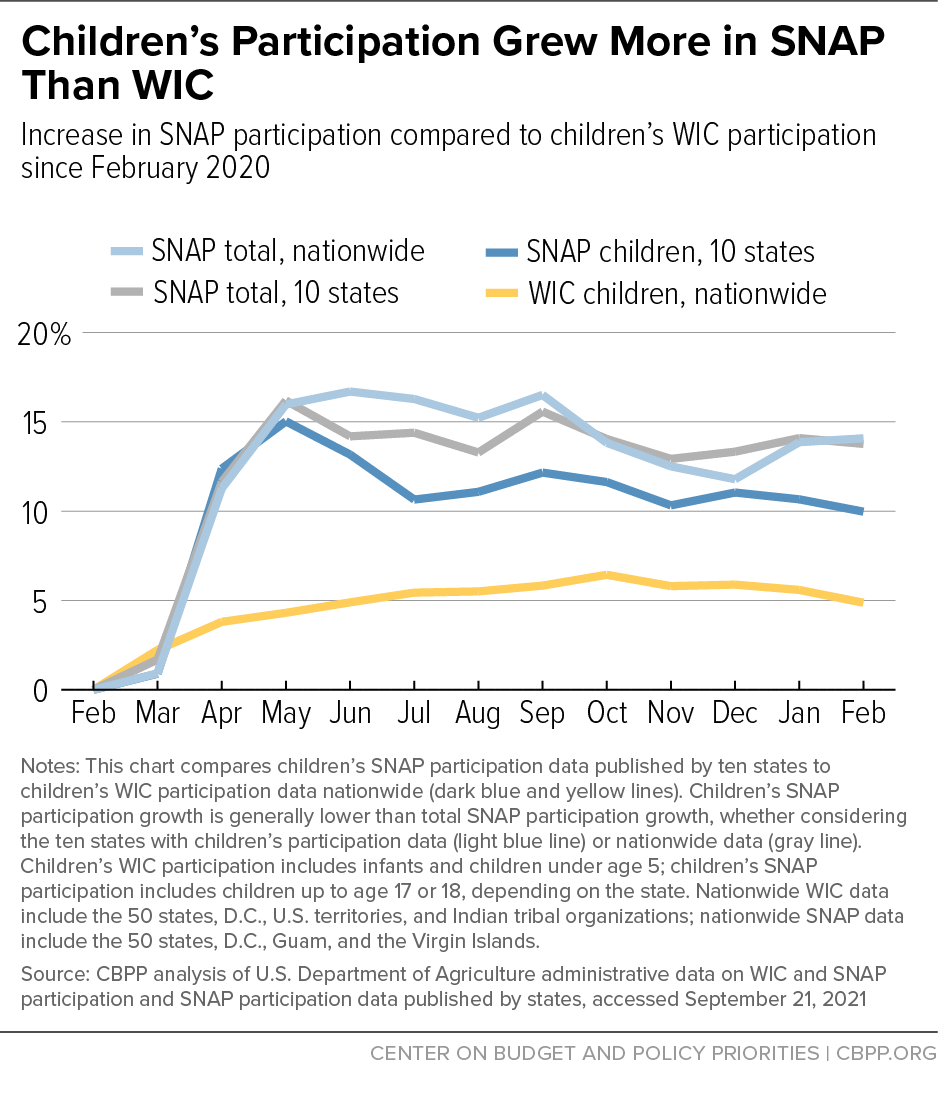

Likewise, nationwide SNAP participation increased by 14 percent between February 2020 and February 2021, compared to just 2 percent for WIC.[7] Nationwide data are not available on the number of children participating in SNAP, but in the ten states that publish SNAP participation data for children, it increased by 10 percent from February 2020 to February 2021, while nationwide WIC participation by infants and young children increased by 5 percent.[8] Because Medicaid and SNAP participants are automatically income-eligible for WIC, WIC’s slower growth provides additional evidence that the share of eligible families participating in WIC has likely declined further during the pandemic.

While food hardship has started to decline in 2021 as more relief has reached low-income families, the number of children in households where children aren’t getting enough to eat appears to be many times higher than pre-pandemic levels, according to our analysis of a separate Census Bureau survey conducted in December 2019.[9] (Methodological differences between the two surveys explain some, but not all, of the increase.[10]) Clearly, many eligible families are not receiving the assistance they need, and many young children who could be benefitting from the health and developmental improvements associated with WIC participation are being left behind.

By working together, state WIC, Medicaid, and SNAP leaders can use data to assess the extent to which WIC is reaching eligible families and take steps to enroll more of them so that low-income young children do not miss out on critical assistance at a time when food hardship is disturbingly high.

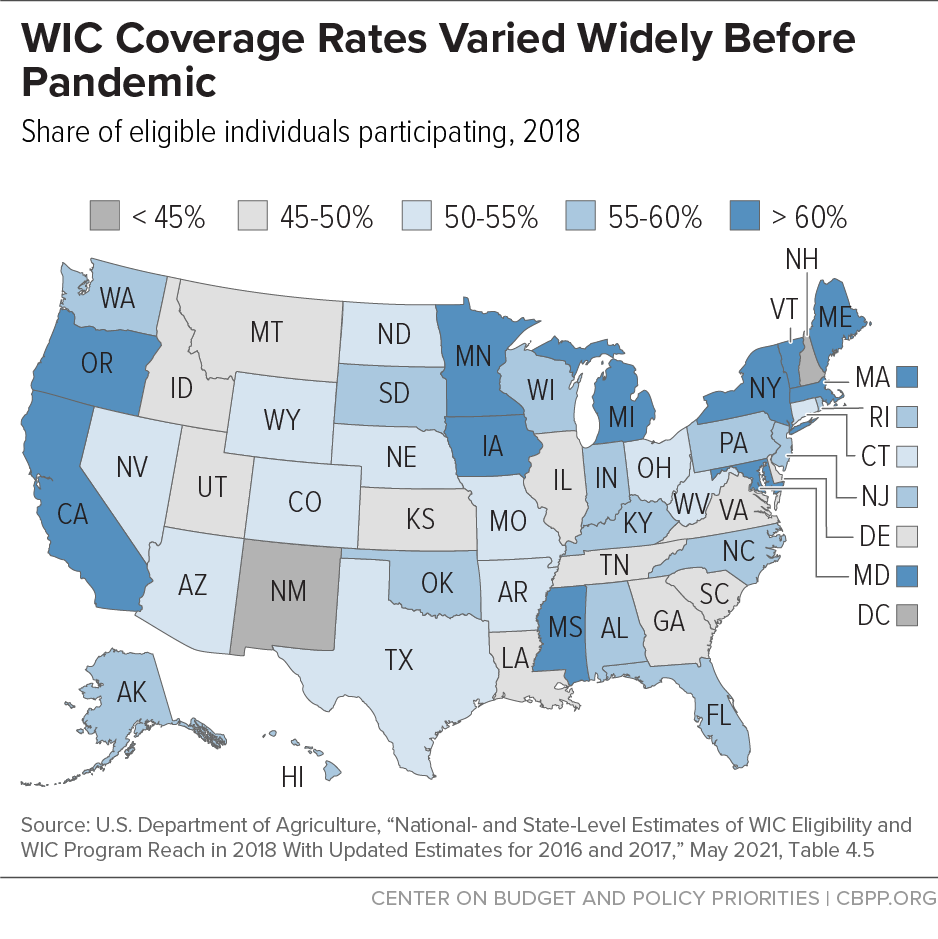

Since 2005, the Department of Agriculture (USDA) has issued detailed annual estimates of the number of individuals eligible for WIC by state, population category, and race and has compared the actual number of participants to the estimated number of eligible people to estimate a “coverage rate” — the share of eligible individuals the program is reaching.

The WIC coverage rate was already declining prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, falling between 2011 and 2015.[11] Revised coverage rate estimates that USDA recently released for 2016 and 2017 and new estimates it released for 2018 suggest that the decline might have levelled off, but a change in the underlying Census data renders them not comparable to earlier years.[12] Regardless of the trend, the coverage rate for 2018 confirms that many eligible low-income families are missing out on WIC’s proven benefits: nationwide, WIC reached only 57 percent of eligible individuals. While nearly all eligible infants participated in WIC, only 53 percent of eligible pregnant individuals participated, as did only 44 percent of eligible children ages 1 through 4. Coverage rates in 2018 also varied widely across states, ranging from 44 percent to 75 percent. (See Figure 1.)

Maternal and infant mortality and associated risk factors are higher for families of color than for white families. Black and Latino women have higher risk of severe pregnancy-related health issues such as preeclampsia. Pregnancy-related deaths are much rarer than other serious pregnancy-related health issues, but they have increased substantially over the past three decades and remain disturbingly high even though most are preventable. Black people are three times likelier to die due to pregnancy than white people. Black, Native American, and Pacific Islander people also have higher shares of preterm births, low birthweight births, or births for which they received late or no prenatal care, compared to white people. In part as a result of these factors, infants of these groups are roughly twice as likely to die as white infants.a

Likewise, Black and Latino families have long experienced higher levels of food hardship, reflecting longstanding inequities — often stemming from structural racism — in education, housing, health care, and employment. The COVID-19 pandemic further exacerbated racial disparities in food hardship. The share of households with children where children were food insecure at times during 2020 remained constant at 5 percent for white households with children, while it increased to 13 percent for Black households with children and 12 percent for Latino households with children.b Given that increased food assistance was provided throughout the pandemic, the disparities in food hardship likely would have been even greater without this relief.c

Due to racial disparities in income, Black and Latino individuals are more likely to be eligible for WIC than white individuals. (In 2018, 65 percent of Black and 63 percent of Latino individuals were eligible, compared to 31 percent of white individuals.) Among WIC participants in 2018, 41 percent identified as Latino, 29 percent as white, 20 percent as Black, 4 percent as Asian, 1 percent as Pacific Islander, and 1 percent as American Indian.d

Because WIC has the potential to reduce disparities in health and food hardship, it is important to examine coverage rates by race and ethnicity. Eligible Black and Latino infants and children participate in WIC at higher rates than white children, which may indicate that WIC is already reducing child health disparities.e But pregnant individuals who are white participate at higher rates than those who are Black or Latino. Given the stark racial disparities in pregnancy-related health outcomes, it is important for WIC to reach a greater share of Black and Latino pregnant individuals. More broadly, regardless of relative coverage rates, many Black and Latino pregnant individuals and children are missing out on WIC; enrolling more eligible families could help reduce racial disparities in food hardship, maternal and child health, and child development, as well as support people facing hardship.

a Samantha Artiga et al., “Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Health: An Overview,” Kaiser Family Foundation, November 10, 2020, https://www.kff.org/report-section/racial-disparities-in-maternal-and-infant-health-an-overview-issue-brief/.

b Alisha Coleman-Jensen et al., “Household Food Security in the United States in 2020,” U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, September 2021, p. 21, Table 3, https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/102076/err-298.pdf?v=3714.5.

c Ibid. p. 1 and Jason DeParle, “Vast Expansion in Aid Kept Food Insecurity From Growing Last Year,” New York Times, updated September 11, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/08/us/politics/vast-expansion-aid-food-insecurity.html.

d Race and ethnicity are reported separately. For the combined race and ethnicity shares listed here, the Latino category represents individuals who identified as Hispanic/Latino. The white, Black, Asian, Pacific Islander, and American Indian categories represent people who identified as that racial category and did not identify as Hispanic/Latino. Four percent of participants identified as more than one race (and did not identify as Hispanic/Latino). In some instances, the race/ethnicity of a participant is based on the observation of a WIC staff member rather than self-reported by the participant, which may limit the accuracy of the race and ethnicity data. See Nicole Kline et al., “WIC Participant and Program Characteristics 2018: Final Report,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, May 2020, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/WICPC2018.pdf.

e See Kelsey Gray et al., “National- and State-Level Estimates of WIC Eligibility and WIC Program Reach in 2018 With Updated Estimates for 2016 and 2017,” USDA, May 2021, https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/WICEligibles2018-VolumeI.pdf.

WIC Participation Changes in Pandemic Varied Widely by State

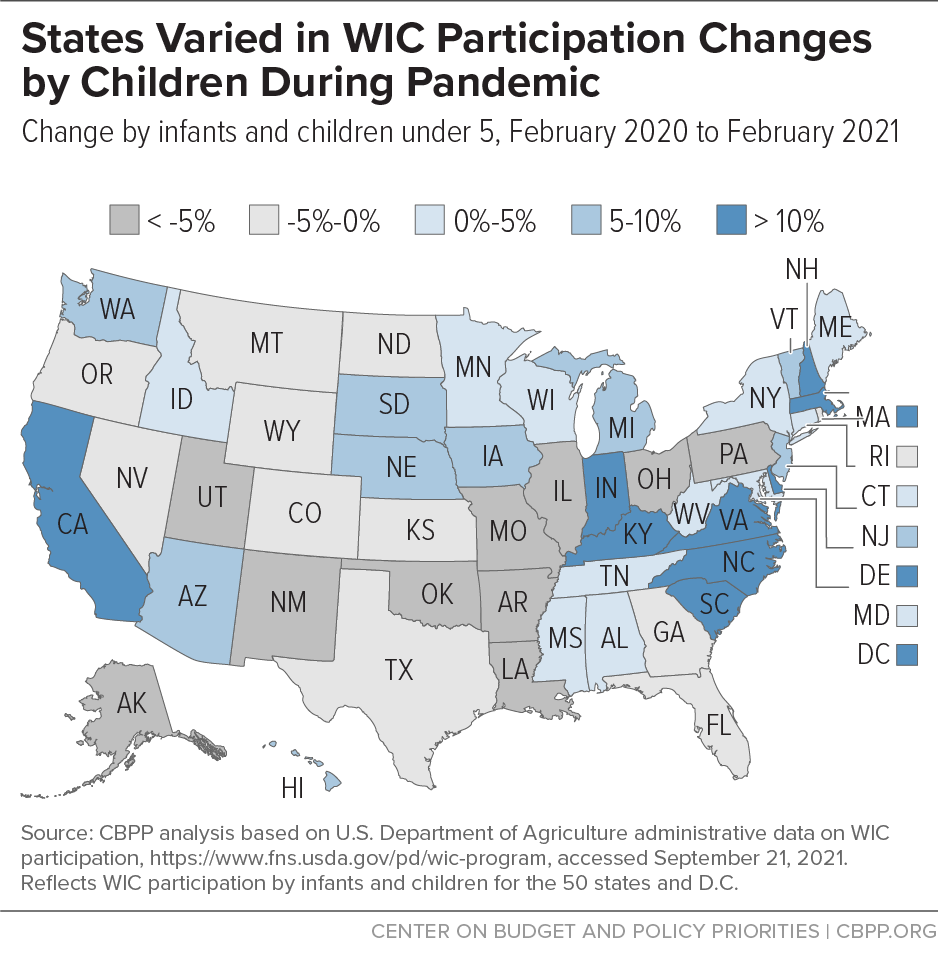

Nationwide, WIC participation increased by 2 percent between February 2020 and February 2021. But the changes varied widely by state, ranging from a 20 percent increase to a 21 percent decrease. Nineteen states plus the District of Columbia grew by more than 2 percent; the rest had smaller growth or declined.

Similarly, changes in WIC participation among children ranged from a 25 percent gain to a 22 percent decline. (See Figure 2.) Eighteen states plus D.C. grew by more than the nationwide figure of 5 percent; the rest had small growth or declined. (See Figure 3.)

WIC participation by pregnant and postpartum people declined by nearly 5 percent nationwide over the same period, with states ranging from a 20 percent decline to a 7 percent increase. A nationwide decline during a period when food hardship was so high and pregnant people faced additional health risks related to COVID-19 is concerning. However, while the COVID-19 crisis likely made more adults income-eligible for WIC, it also led to a decrease in the number of people getting pregnant, which could have reduced the number of adults eligible for WIC. Births have been decreasing since 2007 (by just over 1 percent annually between 2007 and 2019, on average), and provisional data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services show a further 4 percent decline between 2019 and 2020.[13] Researchers also predict a decline in births in 2021 due to fewer pregnancies during the pandemic.[14]

There were in fact fewer births in November and December 2020 than earlier in the year, which indicates a decline in pregnancies as the pandemic set in in February and March 2020, but without data for 2021 we do not yet know if this decline was sustained.[15] Moreover, the 2020 data and 2021 projection don’t distinguish by income, so the recent trend might differ for low-income women. Because we do not yet know whether the number of WIC-eligible pregnant and postpartum women increased or decreased during the pandemic, this analysis focuses on participation by children under 5.

At this point we do not know why WIC participation changes varied so much across states, but one factor that has been shown to be associated with declines is that some states can’t remotely load WIC benefits onto electronic benefit cards, so participants must travel to the WIC clinic or drop off their card to receive their benefits — which some people may have been reluctant to do during the health crisis.[16] Every state that couldn’t remotely load benefits experienced a decline in total WIC participation and participation by infants and children between February 2020 and February 2021.

Several other factors may be contributing to smaller participation increases or actual declines. Though 2020 was the deadline for states to implement electronic benefits, some states were still implementing them or were still issuing paper vouchers, posing a burden and health risk for participants to obtain them. In addition, outreach during the pandemic may have been difficult, and some participants and potential applicants may not have been aware that services were being offered remotely while WIC clinics were closed. Moreover, some staff may have been redeployed to COVID-19 work, leaving state and local WIC agencies with fewer staff. Lastly, some WIC-eligible families received other assistance, such as increases to SNAP benefits or economic impact payments, that might have reduced their need for WIC benefits.[17] The fact that WIC participation increased substantially in some states, however, suggests that factors like this, which applied to all states, were not necessarily the driving force behind differences in WIC participation.

Declines in WIC participation, or even small increases, even as food hardship grew substantially indicate that WIC is not keeping up with need. In addition, the high levels of food hardship during the pandemic raise serious concerns about the long-term consequences for children’s health and development — particularly for children of color, given the extreme inequity in food hardship rates. Not getting enough to eat, or eating less nutritious food, can have lasting effects on children’s health, leading to problems that can lower children’s test scores, their likelihood of graduating from high school, and their earnings in adulthood.[18] Even short periods of food insecurity pose long-term risks for children.

To assess how effectively WIC is reaching eligible families during the pandemic, it is also instructive to compare participation changes in WIC to those in Medicaid, which provides access to comprehensive health care, and in SNAP, which offers grocery benefits to help individuals and families afford food. Medicaid and SNAP participants are “adjunctively eligible” for WIC, which means they are considered income-eligible and do not need to separately document their income to enroll in WIC.[19] Thus, examining the number of pregnant and postpartum people and children under 5 who participate in Medicaid and SNAP gives one indication of the universe of individuals WIC could be reaching.[20]

Historically, WIC participation has overlapped heavily with Medicaid and SNAP. In 2018, about 77 percent of WIC applicants also participated in Medicaid and about 33 percent also participated in SNAP.[21] While there are no comparable national figures on the share of WIC-eligible Medicaid and SNAP participants who also participated in WIC, every pregnant or postpartum individual and child under 5 participating in Medicaid or SNAP would have been eligible for WIC through adjunctive eligibility.

Yet even before the pandemic, a substantial share of Medicaid and SNAP participants who were income-eligible for WIC were not enrolled. Pilot projects conducted in four states during 2018 and 2019 offer a window into the extent to which Medicaid and SNAP participants were missing out on WIC. Based on data matching, these states found that between 44 percent and 63 percent of WIC-eligible people enrolled in Medicaid or SNAP were not enrolled in WIC.[22]

Medicaid enrollment has grown steadily over the course of the pandemic, driven by two main factors. First, the economic crisis resulted in high rates of unemployment. As families lost income, more became eligible for Medicaid and people who had already been eligible for Medicaid but were covered by employer-provided health insurance turned to Medicaid when they lost that coverage.

Second, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act established a “continuous coverage” provision that prohibits states from terminating a participant’s Medicaid coverage during the public health emergency unless the person requests termination, moves out of the state, or dies. This provision will remain in effect until the end of the federal public health emergency, which is expected to last at least through 2021.

Continuous coverage has eliminated gaps in Medicaid coverage that often occur when people’s incomes rise modestly over program limits for short periods of time or they fail to return needed paperwork. For example, enrollees often lose coverage despite remaining eligible because they don’t receive a notice or can’t produce paperwork to document their income. Continuous coverage has likely led more eligible families to participate in Medicaid, so while it allows families to continue participating even if their income increases above the eligibility limit, current Medicaid enrollment may represent the universe of families that are also eligible for WIC more accurately than enrollment prior to continuous coverage.[23]

Total Medicaid enrollment increased by 16 percent in the 50 states and D.C. between February 2020 and February 2021, while WIC participation increased by only 3 percent.[24] Because Medicaid covers seniors and people with disabilities, comparing Medicaid enrollment by children of all ages to WIC participation by children under 5 may be more relevant.[25] Among the 50 states and D.C., Medicaid child enrollment increased by roughly 11 percent over this period while WIC child participation increased by roughly 5 percent. (See Figure 4.) Medicaid’s enrollment increase reflects continuous coverage, but all Medicaid participants are income-eligible for WIC, so WIC’s lower growth suggests that the number of young children participating in Medicaid who are eligible for WIC but missing out has risen since the pandemic started.[26]

In fact, if all new Medicaid participants under age 5 had also enrolled in WIC, WIC participation would have grown by a larger percentage than Medicaid because WIC serves fewer children under age 5 than Medicaid does. Consider Maryland as an example. Between February 2020 and February 2021, the number of children under 5 enrolled in Medicaid rose by 5,947 (3 percent) while the number of infants and children under 5 participating in WIC rose by just 2,048 (2 percent). If WIC had added 5,947 children, its participation would have grown by 7 percent, exceeding Medicaid’s 3 percent growth.

Although we don’t know whether Medicaid enrollment grew at the same rate for children under 5 as for children of all ages, the fact that WIC participation by children under 5 grew more slowly than Medicaid enrollment of children suggests that substantial numbers of WIC-eligible children are not receiving benefits.

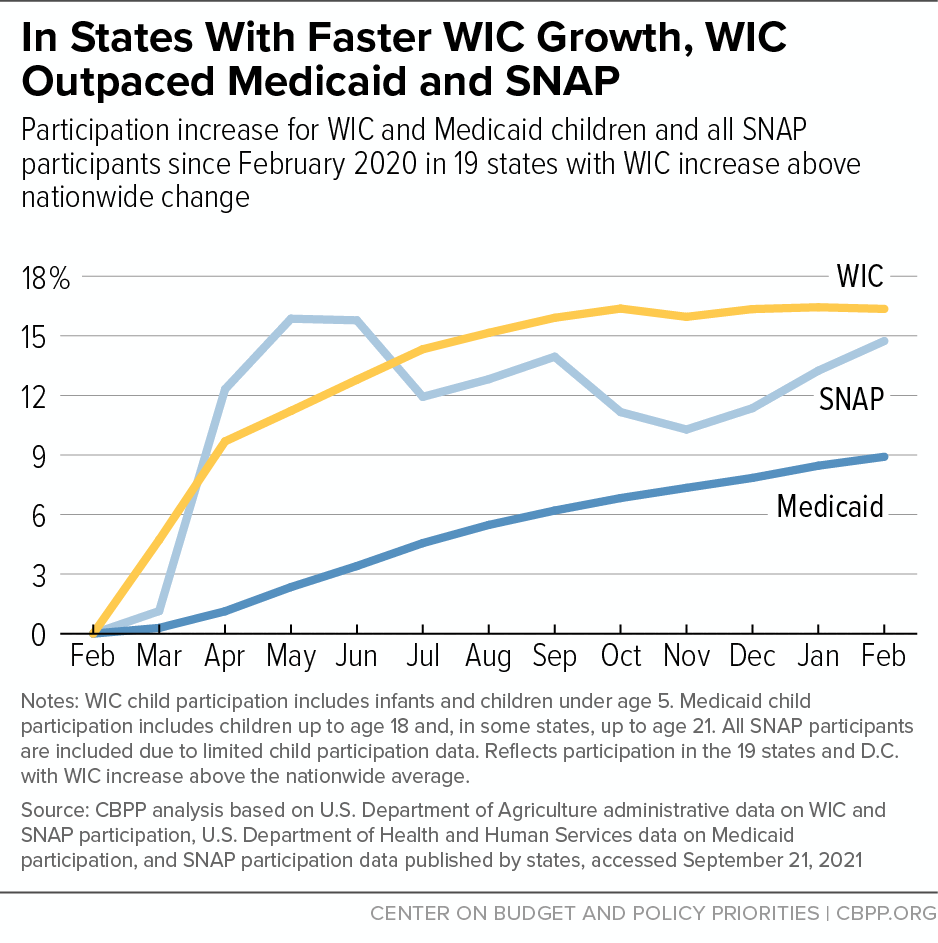

In addition, the fact that WIC participation by children in some states has increased by as much as 25 percent shows that other states can improve in this area. In the 18 states and D.C. where WIC participation growth exceeded the nationwide rate, WIC participation growth exceeded Medicaid enrollment growth; WIC child participation grew by 16 percent from February 2020 to February 2021, far surpassing the 9 percent increase in Medicaid child enrollment. (See Figure 6.) This suggests that some states’ WIC coverage rates may have improved during the pandemic.

During this time of increased need and reduced barriers to participation in Medicaid, states have an important opportunity to try to enroll these children in WIC so they can benefit from its impact on health and development. Conducting data matching to identify WIC-eligible children who are not enrolled and targeting outreach to their families has been shown to increase WIC certification.[27] Given the recent rise in children receiving Medicaid, now is an opportune time to conduct that data matching.

While pregnant and postpartum adults participating in Medicaid are eligible for WIC up to six months postpartum (12 months if breastfeeding), our analysis focuses on participation by children because it is difficult to accurately assess which adults in the Medicaid pregnancy-related enrollment category are eligible for WIC. Prior to the pandemic, pregnant individuals typically remained eligible for Medicaid for 60 days after childbirth.[28] Because of the continuous coverage provision, individuals enrolled in the pregnancy-related enrollment category may remain in that category well past 60 days postpartum. They may also be transferred to another category if its benefits equal or exceed those in the pregnancy-related enrollment category, but the extent to which states are doing this is unclear.[29] Consequently, some individuals may still be in the pregnancy-related enrollment category well after the point at which their WIC eligibility ends. The complexity of determining which Medicaid adult participants are eligible for WIC highlights the importance of delving into state data to determine who is missing out on WIC and how to enroll them.

While there are gaps in the available SNAP data, the data that are available suggest that SNAP participation has grown more rapidly than WIC during the pandemic, providing further evidence that WIC coverage has likely declined. Total SNAP participation increased by 14 percent between February 2020 and February 2021 nationwide, while WIC participation increased by only 2 percent.[30]

As with Medicaid, using SNAP and WIC child participation data may allow for a sounder comparison. While USDA does not publish recent child participation data for SNAP, ten states do, and a comparison using these data can indicate the extent to which more SNAP participants could be enrolled in WIC. In these ten states, SNAP participation by children of all ages increased by 10 percent over this period; nationwide, WIC participation by children under 5 increased by 5 percent.[31] If these ten states are representative, child participation nationally grew by roughly half as much in WIC as in SNAP. (See Figure 5.)

Three facts suggest that those ten states (which accounted for 26 percent of total SNAP participation over this period, on average) are indeed representative. First, as Figure 5 illustrates, the recent trend in the ten states for total SNAP participation (not just among children) is very similar to the national trend. Second, the increase in SNAP child participation among these ten states during the Great Recession (22 percent) was very similar to the increase nationally (23 percent).[32] Third, during the Great Recession SNAP participation grew slightly less among children than among the overall population in the vast majority of states, and it appears the same has been true in these ten states during the pandemic.[33]

SNAP participation growth didn’t outpace WIC in every state. In the 18 states and D.C. where WIC participation growth by children exceeded the nationwide WIC rate between February 2020 and February 2021, it also slightly exceeded the growth in total SNAP participation: 16 percent versus 15 percent. This suggests there is potential for states with lower increases or declines in WIC child participation to enroll more eligible individuals. Matching SNAP data and WIC would allow for targeted outreach to enroll SNAP participants who are adjunctively eligible for WIC.

Overall, these data suggest that the number of children receiving SNAP who are eligible for WIC but not participating may have grown over the pandemic period. More broadly, given the longer-term decline in WIC participation and the evidence that many SNAP participants who are eligible for WIC aren’t getting WIC benefits, efforts to boost WIC participation among SNAP participants could expand access to WIC’s nutrition, health, and developmental benefits.

Various factors affect participation in Medicaid or SNAP that are not applicable across WIC, Medicaid, and SNAP.

Medicaid. Medicaid has a larger base of participants than SNAP, so even if Medicaid enrollment grew by a smaller percentage than SNAP during the pandemic, the number of new Medicaid participants might have increased by more. In addition, during a crisis, people may swiftly apply for food assistance because they need to eat every day but may not apply for health coverage until a health issue arises, which may cause faster participation growth in programs like SNAP than in Medicaid. On the other hand, in some states the income limit is higher for Medicaid than for WIC or SNAP, so some Medicaid participants may not be eligible for SNAP and may only qualify for WIC adjunctively upon enrolling in Medicaid.

As noted in this report, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act’s continuous coverage provision, effective March 2020, prohibits states from ending a person’s Medicaid coverage unless they request termination, move out of the state, or die. Continuous coverage will remain in effect until the end of the federal public health emergency, which is expected to last at least through 2021. As a result, individuals who would have become ineligible or lost benefits because they experienced a change or did not recertify can remain enrolled in Medicaid. They also remain adjunctively eligible for WIC so long as they are within six months postpartum (or 12 months if breastfeeding), even though they otherwise might not have been eligible.

Families First also established special Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (PUC) benefits, which provided an additional $600 weekly in unemployment insurance benefits from April through July 2020. The December 2020 COVID-19 relief bill provided an additional $300 weekly from January through mid-March 2021, which the American Rescue Plan extended until early September 2021. These benefits are not considered as income when determining Medicaid eligibility but are considered as income by WIC.a

SNAP. As of April 1, 2020, Families First temporarily suspended the three-month limit on SNAP benefits for unemployed, non-elderly adults not living with minor children in recognition of the pandemic’s impact on the labor market and unemployed workers’ need for food assistance. (The suspension will be in place through the public health emergency.) Some of the increase in SNAP participation during the pandemic may be due to these non-elderly adults gaining SNAP eligibility. They would not be eligible for WIC unless they were pregnant.

The $600 weekly Pandemic Unemployment Compensation benefits established by Families First were considered countable income by SNAP. But the $300 weekly benefits established by the December relief bill and extended by the American Rescue Plan are not countable for SNAP, though they are counted by WIC.

In the ten states that have published child participation data for SNAP, we estimate that children account for about 36 percent, on average, of the participation increase that their data show from February 2020 through February 2021. It should be noted that these ten states do not include some of the states with the highest numbers of SNAP participants.

State and Local Officials Can Boost WIC Participation

The wide variation in WIC participation during the pandemic across states suggests that there are practices that could help state WIC programs reach more eligible families.[34] But support from other state policy leaders, including Medicaid and SNAP officials, will be critical to expanding WIC’s reach.

Recent COVID-19 relief bills have expanded Medicaid and SNAP eligibility to allow more low-income families to qualify and remain enrolled, reducing procedural hurdles that may have precluded participation previously. These policy changes, combined with rising hardship during the COVID-19 health and economic crises, have resulted in substantial increases in Medicaid and SNAP participation. Through adjunctive eligibility, new Medicaid and SNAP participants are also eligible for WIC.

Comparing WIC participation to Medicaid and SNAP participation can inform state and local efforts to enroll more eligible families in WIC by indicating the extent to which WIC is keeping up with need and the potential benefits of targeting WIC outreach to Medicaid and SNAP participants. This is especially important at this time, while procedural barriers have been removed and a greater share of eligible families are participating in Medicaid. The state data in the Appendix and companion interactive data visualization facilitate such a comparison.[35]

This analysis provides a starting point for such a comparison, but there are limitations in the published national and state data. Fortunately, Congress in 2020 directed USDA to begin publishing state-level estimates of pregnant individuals, infants, and children under 5 who are participating in Medicaid or SNAP but not WIC; when these data become available, they will better illuminate the gaps between WIC participation and Medicaid and SNAP participation.[36]

By partnering with their state Medicaid and SNAP counterparts, state WIC officials could conduct more robust comparisons of participation in each program among children under 5 and pregnant or postpartum individuals. State officials could analyze factors not available publicly, like the age or income level of WIC-eligible individuals who are not enrolled. They could also generate comparisons at the county or local level. Such a partnership could also enable them to:

- Identify Medicaid and SNAP participants who are adjunctively eligible for WIC but are not enrolled.

- Implement robust referrals from Medicaid or SNAP to WIC.

- Ensure that staff who conduct certifications can rely on adjunctive eligibility whenever possible by, for example, establishing online access to Medicaid and SNAP enrollment data or an automated telephone system to confirm Medicaid or SNAP eligibility.

- Conduct targeted outreach to enroll more eligible families in WIC. Pilot projects suggest that individual outreach to eligible families can boost WIC participation.[37]

Together, state WIC, Medicaid, and SNAP leaders can use data to assess the extent to which WIC is reaching eligible families, take steps to enroll more of them, and measure progress over time. Under typical circumstances, the gap between Medicaid and SNAP participation and WIC is worrisome; under the current circumstances it is alarming, given that hardship is significantly higher due to the COVID-19 pandemic and recession. Ensuring that young low-income children receive the full package of supports for which they are eligible can prevent short-term hardship and put children on a healthier course for life.

This report considers overall participation in WIC, Medicaid, and SNAP between February 2020 and February 2021 as a starting point for analysis but focuses on participation by children. To estimate the number of individuals WIC could reach, it would be ideal to examine the number of pregnant and postpartum people and children under 5 who participate in Medicaid and SNAP. Data are available on overall child participation in Medicaid and SNAP, but data on pregnant and postpartum people and children under 5 are limited. In addition, it is unclear how changes in pregnancy and birth rates during the pandemic affected the number of individuals eligible for WIC or Medicaid.[38]

WIC. USDA typically publishes monthly state participation data for WIC within two to three months.[39] In addition to total participation data, it also publishes data on the number of pregnant and postpartum people, infants, and children ages 1-4 who are participating. Data have been published for the 50 states, D.C., U.S. territories, and Indian tribal organizations.

Medicaid. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) publishes monthly state enrollment data for Medicaid within five or six months.[40] While HHS does not publish child enrollment data for Medicaid, it publishes combined child enrollment data for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). To derive Medicaid child enrollment, we subtract total CHIP enrollment from total child enrollment for Medicaid and CHIP.[41] Data have been published for the 50 states and D.C..[42] Some states have also published Medicaid enrollment data.

SNAP. USDA typically publishes monthly state participation data for SNAP within two to three months.[43] Data have been published for the 50 states, D.C., Guam, and the Virgin Islands. While USDA does not publish child participation data, some states do; ten states have published data for February 2020 through February 2021.[44]

| TABLE 1 |

| |

WIC |

Medicaid |

SNAP |

| State |

Total |

Children |

Pregnant and Postpartum |

Total |

Children |

Total |

Children |

| Total |

2% |

5% |

-5% |

16% |

11% |

14% |

10% |

| Alabama |

0% |

3% |

-11% |

12% |

8% |

13% |

|

| Alaska |

-7% |

-5% |

-13% |

11% |

8% |

-3% |

|

| Arizona |

6% |

9% |

-4% |

17% |

13% |

16% |

21% |

| Arkansas |

-21% |

-22% |

-20% |

13% |

7% |

3% |

|

| California |

18% |

21% |

6% |

10% |

6% |

10% |

|

| Colorado |

-1% |

-1% |

-3% |

21% |

14% |

18% |

|

| Connecticut |

-1% |

1% |

-8% |

12% |

6% |

4% |

|

| Delaware |

7% |

11% |

-6% |

14% |

12% |

-3% |

|

| District of Columbia |

16% |

22% |

1% |

10% |

7% |

32% |

|

| Florida |

-2% |

-1% |

-8% |

19% |

16% |

27% |

|

| Georgia |

-7% |

-4% |

-15% |

16% |

17% |

29% |

|

| Hawai’i |

4% |

7% |

-5% |

23% |

15% |

30% |

|

| Idaho |

2% |

4% |

-7% |

23% |

14% |

-8% |

|

| Illinois |

-9% |

-8% |

-13% |

16% |

6% |

10% |

|

| Indiana |

13% |

16% |

0% |

23% |

13% |

18% |

|

| Iowa |

4% |

6% |

-2% |

14% |

10% |

0% |

|

| Kansas |

-4% |

-2% |

-10% |

16% |

15% |

7% |

5% |

| Kentucky |

17% |

23% |

-1% |

23% |

11% |

30% |

|

| Louisiana |

-9% |

-9% |

-8% |

15% |

6% |

29% |

15% |

| Maine |

4% |

5% |

-1% |

17% |

12% |

3% |

|

| Maryland |

0% |

2% |

-6% |

13% |

9% |

43% |

|

| Massachusetts |

11% |

14% |

0% |

15% |

7% |

23% |

22% |

| Michigan |

4% |

6% |

-6% |

16% |

10% |

12% |

9% |

| Minnesota |

1% |

3% |

-6% |

14% |

10% |

22% |

|

| Mississippi |

-3% |

1% |

-15% |

13% |

13% |

-3% |

|

| Missouri |

-13% |

-11% |

-17% |

22% |

22% |

6% |

|

| Montana |

-5% |

-3% |

-11% |

13% |

8% |

-6% |

|

| Nebraska |

6% |

8% |

-1% |

31% |

13% |

5% |

|

| Nevada |

-3% |

-2% |

-9% |

25% |

17% |

17% |

|

| New Hampshire |

17% |

19% |

7% |

20% |

11% |

-5% |

|

| New Jersey |

7% |

10% |

-4% |

16% |

12% |

22% |

20% |

| New Mexico |

-9% |

-8% |

-12% |

11% |

8% |

17% |

13% |

| New York |

2% |

5% |

-7% |

14% |

8% |

8% |

|

| North Carolina |

20% |

25% |

5% |

18% |

10% |

17% |

|

| North Dakota |

-1% |

-1% |

-3% |

21% |

19% |

7% |

|

| Ohio |

-10% |

-9% |

-14% |

16% |

11% |

12% |

14% |

| Oklahoma |

-7% |

-6% |

-12% |

24% |

19% |

6% |

|

| Oregon |

-2% |

0% |

-7% |

18% |

8% |

30% |

|

| Pennsylvania |

-9% |

-9% |

-8% |

14% |

11% |

4% |

|

| Rhode Island |

-3% |

-3% |

-3% |

16% |

10% |

-1% |

|

| South Carolina |

17% |

22% |

2% |

11% |

7% |

7% |

|

| South Dakota |

6% |

7% |

2% |

15% |

14% |

-2% |

-4% |

| Tennessee |

0% |

3% |

-8% |

10% |

9% |

7% |

|

| Texas |

-3% |

-1% |

-6% |

20% |

19% |

7% |

2% |

| Utah |

-11% |

-10% |

-15% |

32% |

25% |

-1% |

|

| Vermont |

8% |

10% |

1% |

16% |

7% |

3% |

|

| Virginia |

12% |

17% |

-2% |

19% |

12% |

12% |

|

| Washington |

3% |

5% |

-4% |

13% |

5% |

28% |

|

| West Virginia |

0% |

3% |

-11% |

13% |

9% |

2% |

|

| Wisconsin |

2% |

4% |

-5% |

19% |

14% |

26% |

|

| Wyoming |

-5% |

-4% |

-8% |

20% |

19% |

19% |

|

| TABLE 2 |

| |

Total |

Infants and Children Under 5 |

Pregnant and Postpartum People |

| State |

February 2020 (thousands) |

February 2021 (thousands) |

Change |

February 2020 (thousands) |

February 2021 (thousands) |

Change |

February 2020 (thousands) |

February 2021 (thousands) |

Change |

| Total |

6,110 |

6,262 |

2% |

4,655 |

4,882 |

5% |

1,455 |

1,380 |

-5% |

| Alabama |

112 |

112 |

0% |

84 |

87 |

3% |

27 |

24 |

-11% |

| Alaska |

16 |

15 |

-7% |

12 |

11 |

-5% |

4 |

3 |

-13% |

| Arizona |

124 |

132 |

6% |

96 |

105 |

9% |

27 |

26 |

-4% |

| Arkansas |

62 |

49 |

-21% |

46 |

36 |

-22% |

16 |

13 |

-20% |

| California |

809 |

953 |

18% |

630 |

763 |

21% |

179 |

190 |

6% |

| Colorado |

79 |

78 |

-1% |

61 |

60 |

-1% |

19 |

18 |

-3% |

| Connecticut |

44 |

43 |

-1% |

34 |

34 |

1% |

10 |

9 |

-8% |

| Delaware |

16 |

17 |

7% |

13 |

14 |

11% |

4 |

4 |

-6% |

| District of Columbia |

12 |

14 |

16% |

9 |

11 |

22% |

3 |

3 |

1% |

| Florida |

413 |

403 |

-2% |

314 |

312 |

-1% |

99 |

91 |

-8% |

| Georgia |

198 |

185 |

-7% |

147 |

142 |

-4% |

50 |

43 |

-15% |

| Hawai’i |

25 |

26 |

4% |

19 |

20 |

7% |

6 |

5 |

-5% |

| Idaho |

30 |

30 |

2% |

23 |

24 |

4% |

7 |

7 |

-7% |

| Illinois |

171 |

155 |

-9% |

130 |

119 |

-8% |

41 |

36 |

-13% |

| Indiana |

138 |

155 |

13% |

105 |

123 |

16% |

32 |

32 |

0% |

| Iowa |

57 |

59 |

4% |

44 |

47 |

6% |

13 |

13 |

-2% |

| Kansas |

46 |

45 |

-4% |

36 |

35 |

-2% |

11 |

10 |

-10% |

| Kentucky |

91 |

107 |

17% |

70 |

86 |

23% |

22 |

21 |

-1% |

| Louisiana |

97 |

88 |

-9% |

70 |

64 |

-9% |

26 |

24 |

-8% |

| Maine |

16 |

17 |

4% |

13 |

14 |

5% |

3 |

3 |

-1% |

| Maryland |

119 |

119 |

0% |

90 |

92 |

2% |

28 |

27 |

-6% |

| Massachusetts |

101 |

112 |

11% |

79 |

90 |

14% |

22 |

22 |

0% |

| Michigan |

203 |

211 |

4% |

160 |

170 |

6% |

44 |

41 |

-6% |

| Minnesota |

99 |

100 |

1% |

77 |

80 |

3% |

21 |

20 |

-6% |

| Mississippi |

77 |

75 |

-3% |

59 |

59 |

1% |

18 |

15 |

-15% |

| Missouri |

101 |

88 |

-13% |

75 |

67 |

-11% |

26 |

22 |

-17% |

| Montana |

15 |

14 |

-5% |

12 |

11 |

-3% |

3 |

3 |

-11% |

| Nebraska |

33 |

35 |

6% |

25 |

27 |

8% |

7 |

7 |

-1% |

| Nevada |

58 |

56 |

-3% |

45 |

44 |

-2% |

13 |

12 |

-9% |

| New Hampshire |

12 |

14 |

17% |

10 |

11 |

19% |

2 |

3 |

7% |

| New Jersey |

132 |

141 |

7% |

101 |

111 |

10% |

32 |

30 |

-4% |

| New Mexico |

38 |

35 |

-9% |

29 |

26 |

-8% |

9 |

8 |

-12% |

| New York |

361 |

368 |

2% |

277 |

290 |

5% |

84 |

78 |

-7% |

| North Carolina |

211 |

253 |

20% |

159 |

199 |

25% |

51 |

54 |

5% |

| North Dakota |

10 |

10 |

-1% |

8 |

8 |

-1% |

2 |

2 |

-3% |

| Ohio |

184 |

166 |

-10% |

140 |

128 |

-9% |

44 |

38 |

-14% |

| Oklahoma |

65 |

60 |

-7% |

49 |

46 |

-6% |

16 |

14 |

-12% |

| Oregon |

78 |

76 |

-2% |

61 |

61 |

0% |

17 |

16 |

-7% |

| Pennsylvania |

190 |

174 |

-9% |

147 |

134 |

-9% |

43 |

39 |

-8% |

| Rhode Island |

17 |

17 |

-3% |

14 |

13 |

-3% |

4 |

4 |

-3% |

| South Carolina |

75 |

87 |

17% |

55 |

67 |

22% |

20 |

20 |

2% |

| South Dakota |

14 |

15 |

6% |

11 |

12 |

7% |

3 |

3 |

2% |

| Tennessee |

111 |

111 |

0% |

81 |

83 |

3% |

30 |

28 |

-8% |

| Texas |

678 |

660 |

-3% |

488 |

482 |

-1% |

190 |

178 |

-6% |

| Utah |

41 |

37 |

-11% |

31 |

28 |

-10% |

10 |

8 |

-15% |

| Vermont |

11 |

12 |

8% |

9 |

9 |

10% |

2 |

2 |

1% |

| Virginia |

109 |

122 |

12% |

83 |

96 |

17% |

26 |

26 |

-2% |

| Washington |

121 |

125 |

3% |

94 |

99 |

5% |

27 |

26 |

-4% |

| West Virginia |

33 |

33 |

0% |

25 |

26 |

3% |

8 |

7 |

-11% |

| Wisconsin |

86 |

87 |

2% |

68 |

70 |

4% |

18 |

17 |

-5% |

| Wyoming |

7 |

7 |

-5% |

6 |

5 |

-4% |

2 |

2 |

-8% |

| TABLE 3 |

| |

Total |

Children |

| State |

February 2020 (thousands) |

February 2021 (thousands) |

Change |

February 2020 (thousands) |

February 2021 (thousands) |

Change |

| Total |

64,559 |

74,584 |

16% |

29,386 |

32,733 |

11% |

| Alabama |

752 |

838 |

12% |

489 |

530 |

8% |

| Alaska |

206 |

230 |

11% |

81 |

87 |

8% |

| Arizona |

1,608 |

1,875 |

17% |

655 |

738 |

13% |

| Arkansas |

769 |

866 |

13% |

337 |

360 |

7% |

| California |

10,275 |

11,347 |

10% |

3,491 |

3,715 |

6% |

| Colorado |

1,198 |

1,453 |

21% |

488 |

556 |

14% |

| Connecticut |

825 |

923 |

12% |

311 |

330 |

6% |

| Delaware |

218 |

249 |

14% |

93 |

104 |

12% |

| District of Columbia |

225 |

248 |

10% |

74 |

78 |

7% |

| Florida |

3,360 |

3,997 |

19% |

2,170 |

2,527 |

16% |

| Georgia |

1,619 |

1,872 |

16% |

1,054 |

1,231 |

17% |

| Hawai’i |

300 |

370 |

23% |

113 |

130 |

15% |

| Idaho |

292 |

358 |

23% |

148 |

169 |

14% |

| Illinois |

2,554 |

2,969 |

16% |

1,071 |

1,138 |

6% |

| Indiana |

1,386 |

1,701 |

23% |

701 |

793 |

13% |

| Iowa |

598 |

681 |

14% |

258 |

283 |

10% |

| Kansas |

319 |

369 |

16% |

204 |

235 |

15% |

| Kentucky |

1,193 |

1,468 |

23% |

453 |

503 |

11% |

| Louisiana |

1,382 |

1,592 |

15% |

602 |

639 |

6% |

| Maine |

256 |

300 |

17% |

97 |

109 |

12% |

| Maryland |

1,190 |

1,341 |

13% |

481 |

525 |

9% |

| Massachusetts |

1,350 |

1,555 |

15% |

476 |

507 |

7% |

| Michigan |

2,263 |

2,629 |

16% |

877 |

968 |

10% |

| Minnesota |

1,043 |

1,194 |

14% |

529 |

582 |

10% |

| Mississippi |

538 |

608 |

13% |

340 |

384 |

13% |

| Missouri |

818 |

1,000 |

22% |

500 |

609 |

22% |

| Montana |

227 |

256 |

13% |

89 |

96 |

8% |

| Nebraska |

213 |

279 |

31% |

130 |

147 |

13% |

| Nevada |

584 |

728 |

25% |

254 |

297 |

17% |

| New Hampshire |

166 |

200 |

20% |

74 |

82 |

11% |

| New Jersey |

1,470 |

1,706 |

16% |

580 |

648 |

12% |

| New Mexico |

706 |

785 |

11% |

293 |

317 |

8% |

| New York |

5,376 |

6,138 |

14% |

1,778 |

1,915 |

8% |

| North Carolina |

1,489 |

1,751 |

18% |

908 |

998 |

10% |

| North Dakota |

88 |

106 |

21% |

40 |

48 |

19% |

| Ohio |

2,398 |

2,791 |

16% |

954 |

1,064 |

11% |

| Oklahoma |

593 |

733 |

24% |

379 |

453 |

19% |

| Oregon |

873 |

1,029 |

18% |

288 |

310 |

8% |

| Pennsylvania |

2,749 |

3,140 |

14% |

1,197 |

1,329 |

11% |

| Rhode Island |

256 |

297 |

16% |

83 |

91 |

10% |

| South Carolina |

941 |

1,042 |

11% |

553 |

592 |

7% |

| South Dakota |

94 |

108 |

15% |

62 |

71 |

14% |

| Tennessee |

1,324 |

1,462 |

10% |

696 |

755 |

9% |

| Texas |

3,633 |

4,344 |

20% |

2,736 |

3,260 |

19% |

| Utah |

272 |

360 |

32% |

143 |

179 |

25% |

| Vermont |

146 |

170 |

16% |

56 |

60 |

7% |

| Virginia |

1,270 |

1,507 |

19% |

600 |

671 |

12% |

| Washington |

1,650 |

1,858 |

13% |

753 |

790 |

5% |

| West Virginia |

472 |

536 |

13% |

179 |

194 |

9% |

| Wisconsin |

980 |

1,166 |

19% |

435 |

497 |

14% |

| Wyoming |

52 |

62 |

20% |

33 |

39 |

19% |

| TABLE 4 |

| |

Total |

Children |

| State |

February 2020

(thousands) |

February 2021

(thousands) |

Change |

February 2020

(thousands) |

February 2021

(thousands) |

Change |

| Total |

36,868 |

42,057 |

14% |

4,379 |

4,816 |

10% |

| Alabama |

705 |

793 |

13% |

|

|

|

| Alaska |

80 |

78 |

-3% |

|

|

|

| Arizona |

783 |

907 |

16% |

359 |

434 |

21% |

| Arkansas |

339 |

349 |

3% |

|

|

|

| California |

4,031 |

4,451 |

10% |

|

|

|

| Colorado |

431 |

507 |

18% |

|

|

|

| Connecticut |

360 |

374 |

4% |

|

|

|

| Delaware |

116 |

112 |

-3% |

|

|

|

| District of Columbia |

109 |

143 |

32% |

|

|

|

| Florida |

2,635 |

3,344 |

27% |

|

|

|

| Georgia |

1,343 |

1,734 |

29% |

|

|

|

| Hawai’i |

152 |

198 |

30% |

|

|

|

| Idaho |

148 |

135 |

-8% |

|

|

|

| Illinois |

1,748 |

1,927 |

10% |

|

|

|

| Indiana |

566 |

669 |

18% |

|

|

|

| Iowa |

291 |

290 |

0% |

|

|

|

| Kansas |

190 |

204 |

7% |

88 |

93 |

5% |

| Kentucky |

482 |

625 |

30% |

|

|

|

| Louisiana |

782 |

1,007 |

29% |

364 |

420 |

15% |

| Maine |

154 |

158 |

3% |

|

|

|

| Maryland |

591 |

844 |

43% |

|

|

|

| Massachusetts |

761 |

934 |

23% |

257 |

313 |

22% |

| Michigan |

1,176 |

1,317 |

12% |

477 |

521 |

9% |

| Minnesota |

391 |

478 |

22% |

|

|

|

| Mississippi |

424 |

411 |

-3% |

|

|

|

| Missouri |

657 |

700 |

6% |

|

|

|

| Montana |

106 |

99 |

-6% |

|

|

|

| Nebraska |

153 |

160 |

5% |

|

|

|

| Nevada |

412 |

482 |

17% |

|

|

|

| New Hampshire |

72 |

69 |

-5% |

|

|

|

| New Jersey |

667 |

811 |

22% |

303 |

363 |

20% |

| New Mexico |

445 |

521 |

17% |

183 |

207 |

13% |

| New York |

2,560 |

2,761 |

8% |

|

|

|

| North Carolina |

1,213 |

1,424 |

17% |

|

|

|

| North Dakota |

48 |

51 |

7% |

|

|

|

| Ohio |

1,366 |

1,533 |

12% |

572 |

654 |

14% |

| Oklahoma |

572 |

609 |

6% |

|

|

|

| Oregon |

581 |

754 |

30% |

|

|

|

| Pennsylvania |

1,729 |

1,795 |

4% |

|

|

|

| Rhode Island |

146 |

145 |

-1% |

|

|

|

| South Carolina |

568 |

610 |

7% |

|

|

|

| South Dakota |

78 |

76 |

-2% |

38 |

36 |

-4% |

| Tennessee |

844 |

900 |

7% |

|

|

|

| Texas |

3,162 |

3,396 |

7% |

1,738 |

1,775 |

2% |

| Utah |

165 |

163 |

-1% |

|

|

|

| Vermont |

68 |

70 |

3% |

|

|

|

| Virginia |

680 |

759 |

12% |

|

|

|

| Washington |

797 |

1,017 |

28% |

|

|

|

| West Virginia |

304 |

308 |

2% |

|

|

|

| Wisconsin |

600 |

757 |

26% |

|

|

|

| Wyoming |

26 |

31 |

19% |

|

|

|