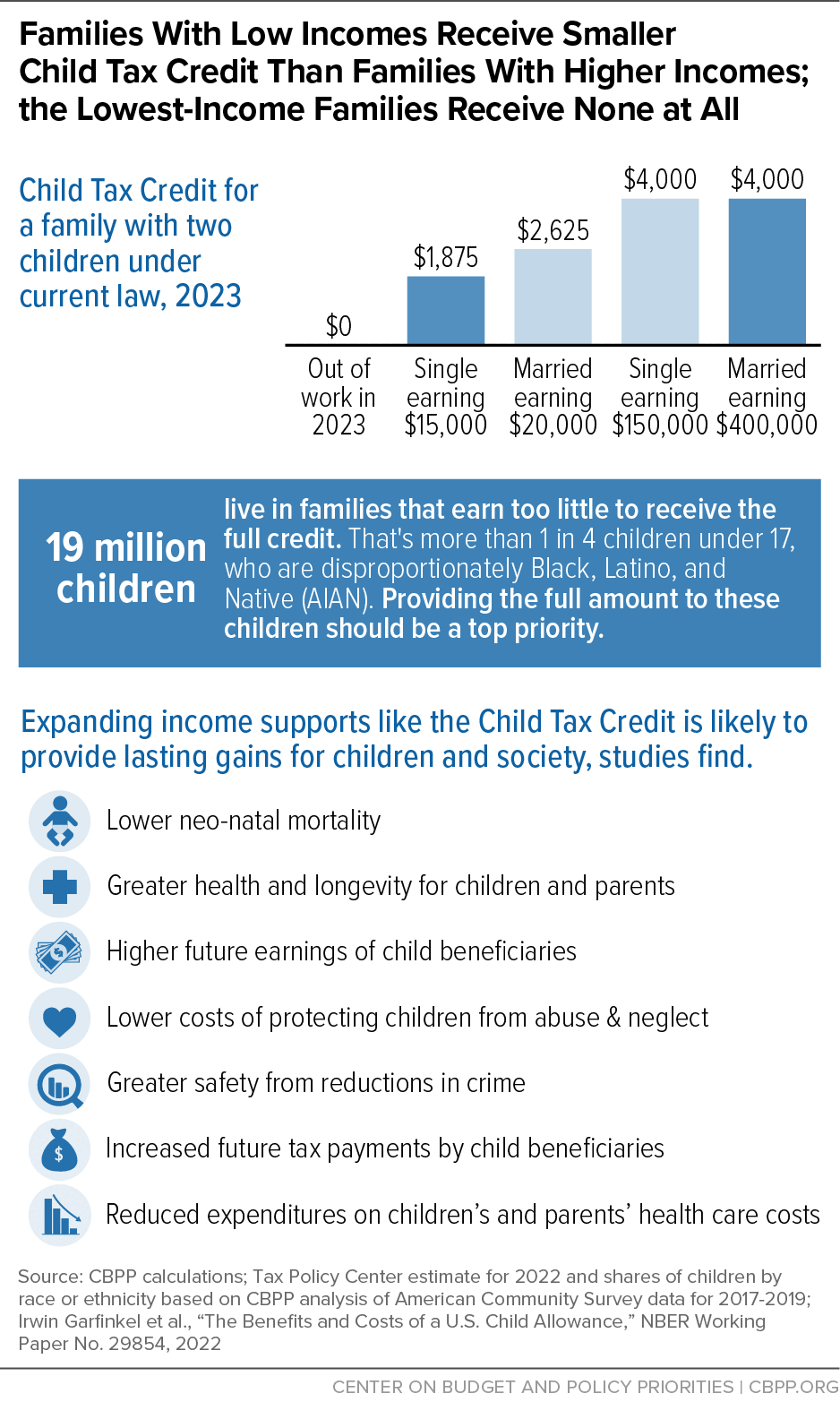

When the temporary Child Tax Credit expansion under the American Rescue Plan expired at the end of 2021, the credit reverted to the flawed design left in place by the 2017 Trump tax law. As a result, an estimated 19 million children — or more than 1 in 4 children under age 17 — will get less than the full Child Tax Credit or no credit at all this year because their families earn too little, while families with much higher incomes (up to $400,000 for married couples) will receive the full $2,000 credit for each child. Republicans on the House Ways and Means Committee are reportedly preparing tax legislation, and expanding the credit for these children should be the top priority in the bill.[1] Congress should ensure that a robust expansion that would help children in families with low incomes meet their basic needs comes before corporate tax breaks that House Republicans are likely to propose.

Making the full $2,000 current Child Tax Credit available to children in families with low incomes or without any earnings in the year — ensuring that low-income children would get the same benefit as those in higher-income families — would have a modest cost of roughly $12 billion per year through 2025, according to the Joint Committee on Taxation.[2] This is far less than the combined cost of tax breaks corporate lobbyists are pushing.[3]

The Republican tax package is expected to include several provisions to reduce the taxes that businesses pay. This includes restoring the more generous tax treatment of research and experimentation (R&E) expenses, which the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates would cost $150 billion over ten years or more than $15 billion per year, on average.[4] In the 2017 tax law, Republican policymakers required companies, starting in 2022, to deduct the cost of their R&E expenses over multiple years (known as amortization) instead of claiming them all in the first year. Republicans put this policy in place starting in 2022 to raise revenues that would help pay for the law’s significant cut in the corporate tax rate, which was a far larger rate cut than had been previously contemplated and was made permanent in the 2017 legislation.

Yet now some policymakers are proposing to reverse the R&E provision without a corresponding increase in the corporate tax rate on profitable corporations that, overall, received very large tax cuts from the 2017 law even with the R&E provision that’s now gone into effect. Not only would reversing the 2017 R&E provision cost significant revenue, it would undo one of the Republicans’ own revenue raisers from the 2017 tax law.

Corporate lobbyists are also pushing policymakers to delay the phase-down of aggressive deductions of businesses’ plant and equipment costs. For tax years 2018 to 2022, the 2017 tax law allowed businesses to deduct 100 percent of the cost of equipment in the year that they bought it, known as “full expensing,” rather than deducting the cost over a set number of years, to reflect that it provides value to the business over time. The law phased down this benefit to an accelerated or “bonus” depreciation schedule from 2023 to 2026 as a way to raise revenues later in the ten-year budget window, which helped reduce the large cost of the 2017 tax cuts.

Permanently extending full expensing of equipment would run a costly $325 billion over ten years, or an average of $33 billion per year, according to a CBO estimate.[5] Congress should not extend more generous expensing without a corresponding increase in the corporate tax rate to make up for this large revenue loss.

Corporate lobbyists are also pushing for a third tax break that would loosen a limit on the amount of interest certain businesses may deduct. In the 2017 law, congressional Republicans imposed a new limit on business interest deductions, and to raise additional revenue, they tightened the limit starting in 2022. Rolling the interest limit back to pre-2022 rules would cost about $20 billion per year, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimated.[6]

Reversing this policy is backward and policymakers should reject this provision. A strong interest deduction limit curtails multinational corporations’ ability to shift profits overseas by making large interest payments to foreign affiliates. It also lowers the existing subsidy for debt-financed investment, which benefits highly leveraged businesses, such as those owned by private equity funds.

Congress should tighten limits on interest deductions, especially if paired with more generous depreciation. That is, if full expensing is combined with interest deductions, businesses that take out loans to buy equipment or other depreciable assets could essentially get a double tax benefit: a full deduction for the price of a purchased asset and a deduction for interest on the debt used to buy that asset. According to Jason Furman, former chair of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, this double benefit is a “nearly fatal problem.”[7]

Corporate tax cuts are regressive, flowing disproportionately to wealthy and foreign shareholders, and they have a long track record of not trickling down. A tax package that serves corporate interests while leaving families behind, therefore, should be unacceptable. Congress should not expand any business tax breaks without including a robust expansion of the Child Tax Credit that would make the full credit permanently available to children in families with low incomes.

This would substantially reduce child poverty at a modest cost. Making the full $2,000 credit available to children in families with low incomes would cost roughly $12 billion per year through 2025, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated. This change would reduce the number of children living in a family with income below the poverty line by roughly 16 percent — or about 1.5 million children — in 2023 relative to current law.[8] Increasing the maximum credit in addition to making the full credit available to children in families with the lowest incomes would further reduce poverty. Increasing the credit alone without making it more available to children in families with the lowest incomes would lower poverty far less.

While making the full credit available to children in families with low incomes would lower child poverty among all races and ethnicities, it would especially help Black, Latino, and American Indian or Alaska Native (AIAN) children, whose families are overrepresented in low-paid work due to past and present hiring discrimination, inequities in educational and housing opportunities, and other sources of inequality. By lifting larger shares of children of color above the poverty line, the expansion would narrow the gaps in child poverty rates by race and ethnicity.

Because children in families with low incomes currently cannot receive the full credit, roughly 46 percent of Black children, 39 percent of AIAN children, 37 percent of Latino children, 17 percent of white children, and 15 percent of Asian children get less than the full credit or no credit at all. Making the credit more available to these children would push back against long-standing inequities, advance family income security, and broaden opportunity.

Raising income for families with children experiencing poverty can improve children’s outcomes in the short and long term. (See Figure 1.) That’s because poverty and the hardships that come with it — unstable housing and frequent moves, inadequate nutrition, and high levels of stress in the family — can take a heavy toll on children; they are associated with lower levels of educational attainment, poorer health in adulthood, and lower earnings in adulthood, a 2019 National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine report on reducing child poverty found.[9]

The temporary expansion of the Child Tax Credit for tax year 2021 in the American Rescue Plan was a striking success. The expansion drove down child poverty sharply that year to historic lows. The expansion also narrowed differences in poverty rates between children of different races and ethnicities. The vast majority of families with low incomes spent their monthly Child Tax Credit payments on basic needs — housing, food, clothing, and utilities — and educational expenses.

Parents continued to re-enter the workforce and take jobs while the expanded Child Tax Credit was in effect. Employment among both parents and non-parents rose by 1.7 percentage points in 2021, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data. Numerous studies looking at the real-world evidence from the temporary expansion of the Child Tax Credit suggest the expanded credit did not meaningfully discourage work among parents. For example, researchers at the University of Michigan examined part- and full-time employment and also labor force participation and found “no significant employment effects for any outcome” — with several other research teams reaching similar conclusions.[10]

The expanded credit expired at the end of 2021. As a result, 3.7 million children fell below the monthly poverty line in January 2022, according to the Center on Poverty & Social Policy at Columbia University.[11]

As policymakers craft tax legislation, they should not put corporate interests ahead of the needs of children. If they don’t act, 19 million children in families with low incomes will continue to get a smaller Child Tax Credit than children in families with higher incomes — or even no credit at all. (See Table 1 below for state-specific estimates by race and ethnicity.) All children should be given the opportunity to thrive, and expanding the Child Tax Credit would take an important step in that direction.

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

|

| State | Total | Latino | White | Black | American Indian or Alaska Native | Asian | Another race or multiple races |

|---|

| Total U.S. | 18,662,000 | 6,595,000 | 6,009,000 | 4,274,000 | 576,000 | 498,000 | 872,000 |

| (Of all children in racial/ethnic group, percent left out) | (27%) | (37%) | (17%) | (46%) | (39%) | (15%) | (26%) |

| Alabama | 361,000 | 39,000 | 137,000 | 167,000 | 4,000 | 2,000 | 13,000 |

| Alaska | 37,000 | N/A | 10,000 | N/A | 17,000 | N/A | N/A |

| Arizona | 477,000 | 278,000 | 102,000 | 28,000 | 64,000 | 5,000 | 14,000 |

| Arkansas | 233,000 | 37,000 | 112,000 | 68,000 | 5,000 | N/A | 10,000 |

| California | 2,310,000 | 1,619,000 | 294,000 | 165,000 | 64,000 | 133,000 | 77,000 |

| Colorado | 224,000 | 114,000 | 75,000 | 15,000 | 12,000 | 4,000 | 9,000 |

| Connecticut | 144,000 | 68,000 | 35,000 | 28,000 | 3,000 | 4,000 | 7,000 |

| Delaware | 48,000 | 11,000 | 14,000 | 19,000 | N/A | N/A | 2,000 |

| District of Columbia | 41,000 | 5,000 | N/A | 34,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Florida | 1,176,000 | 437,000 | 310,000 | 352,000 | 12,000 | 16,000 | 54,000 |

| Georgia | 735,000 | 155,000 | 181,000 | 350,000 | 12,000 | 12,000 | 32,000 |

| Hawai’i | 60,000 | 14,000 | 6,000 | N/A | N/A | 8,000 | 31,000 |

| Idaho | 96,000 | 27,000 | 62,000 | N/A | 5,000 | N/A | 2,000 |

| Illinois | 664,000 | 217,000 | 199,000 | 198,000 | 6,000 | 18,000 | 29,000 |

| Indiana | 396,000 | 64,000 | 217,000 | 79,000 | 3,000 | 7,000 | 27,000 |

| Iowa | 136,000 | 24,000 | 79,000 | 20,000 | 3,000 | N/A | 8,000 |

| Kansas | 150,000 | 43,000 | 74,000 | 16,000 | 4,000 | 4,000 | 10,000 |

| Kentucky | 304,000 | 24,000 | 216,000 | 42,000 | 2,000 | 4,000 | 17,000 |

| Louisiana | 402,000 | 28,000 | 118,000 | 232,000 | 6,000 | 4,000 | 14,000 |

| Maine | 49,000 | N/A | 41,000 | N/A | 3,000 | N/A | N/A |

| Maryland | 245,000 | 54,000 | 56,000 | 110,000 | 3,000 | 9,000 | 15,000 |

| Massachusetts | 243,000 | 101,000 | 81,000 | 32,000 | 4,000 | 13,000 | 14,000 |

| Michigan | 579,000 | 67,000 | 285,000 | 172,000 | 14,000 | 9,000 | 35,000 |

| Minnesota | 214,000 | 34,000 | 83,000 | 60,000 | 15,000 | 13,000 | 12,000 |

| Mississippi | 269,000 | 13,000 | 75,000 | 168,000 | 3,000 | N/A | 7,000 |

| Missouri | 350,000 | 31,000 | 205,000 | 81,000 | 7,000 | 3,000 | 25,000 |

| Montana | 55,000 | 4,000 | 34,000 | N/A | 15,000 | N/A | N/A |

| Nebraska | 88,000 | 28,000 | 39,000 | 9,000 | 4,000 | 3,000 | 5,000 |

| Nevada | 184,000 | 94,000 | 37,000 | 32,000 | 6,000 | 6,000 | 12,000 |

| New Hampshire | 39,000 | 5,000 | 30,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| New Jersey | 373,000 | 165,000 | 93,000 | 85,000 | 3,000 | 14,000 | 15,000 |

| New Mexico | 172,000 | 116,000 | 23,000 | N/A | 36,000 | N/A | N/A |

| New York | 1,075,000 | 393,000 | 327,000 | 229,000 | 17,000 | 75,000 | 41,000 |

| North Carolina | 654,000 | 161,000 | 205,000 | 225,000 | 22,000 | 11,000 | 32,000 |

| North Dakota | 26,000 | N/A | 13,000 | N/A | 8,000 | N/A | N/A |

| Ohio | 698,000 | 64,000 | 370,000 | 189,000 | 10,000 | 8,000 | 60,000 |

| Oklahoma | 276,000 | 64,000 | 108,000 | 37,000 | 58,000 | 3,000 | 14,000 |

| Oregon | 186,000 | 59,000 | 98,000 | 8,000 | 10,000 | 5,000 | 9,000 |

| Pennsylvania | 632,000 | 143,000 | 280,000 | 151,000 | 9,000 | 17,000 | 35,000 |

| Rhode Island | 45,000 | 21,000 | 14,000 | 6,000 | N/A | N/A | 2,000 |

| South Carolina | 340,000 | 42,000 | 108,000 | 167,000 | 4,000 | 2,000 | 18,000 |

| South Dakota | 45,000 | 3,000 | 18,000 | N/A | 23,000 | N/A | N/A |

| Tennessee | 461,000 | 62,000 | 231,000 | 137,000 | 5,000 | 3,000 | 23,000 |

| Texas | 2,120,000 | 1,380,000 | 322,000 | 322,000 | 21,000 | 40,000 | 48,000 |

| Utah | 152,000 | 51,000 | 81,000 | N/A | 6,000 | N/A | 9,000 |

| Vermont | 20,000 | N/A | 17,000 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Virginia | 367,000 | 63,000 | 133,000 | 133,000 | 5,000 | 10,000 | 25,000 |

| Washington | 315,000 | 110,000 | 130,000 | 22,000 | 21,000 | 13,000 | 24,000 |

| West Virginia | 123,000 | 3,000 | 103,000 | 7,000 | N/A | N/A | 8,000 |

| Wisconsin | 250,000 | 48,000 | 115,000 | 57,000 | 11,000 | 7,000 | 13,000 |

| Wyoming | 23,000 | 6,000 | 14,000 | N/A | 3,000 | N/A | N/A |