- Home

- Federal Budget

- Flawed Rationale For Cuts In Core Assist...

Flawed Rationale for Cuts in Core Assistance Programs for Low-Income Families

The House Budget Committee will consider as early as this week a 2018 budget plan that will set a framework for budget, tax, and appropriations bills to follow. Media accounts indicate that it will use the fast-track “budget reconciliation” process to mandate substantial cuts in entitlements — one news report puts the figure at $200 billion — which are likely to come primarily from a range of low-income programs, such as food assistance through SNAP (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as food stamps), basic assistance and employment services through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, and other supports for low- and moderate-income people.

Those calling for deep cuts in basic assistance for people of limited means commonly use two arguments to defend their proposals — that spending on these programs is “out of control” and that the cuts constitute “welfare reform” that will help people get jobs. Both claims are specious.

Low- and Moderate-Income Programs Aren’t Driving Long-Term Fiscal Challenges

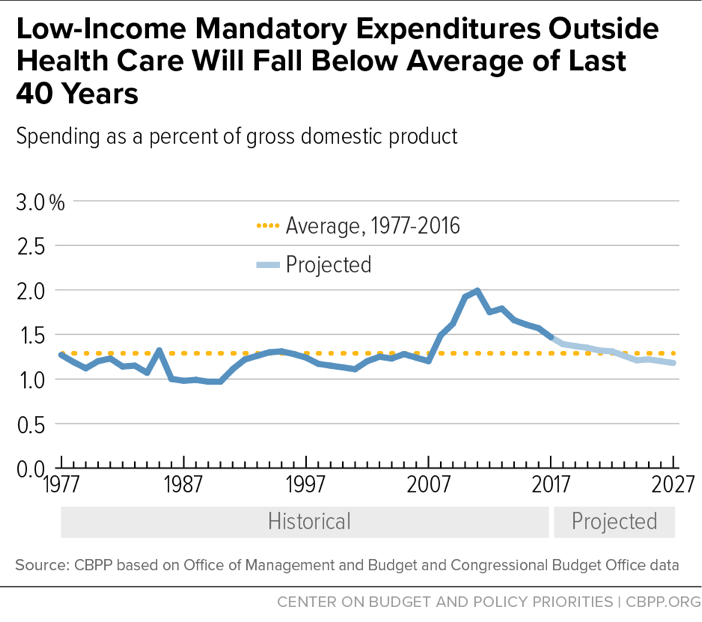

Programs for low- and moderate-income people are not driving the nation’s long-term fiscal problems.Despite assertions by some policymakers and analysts, programs for low- and moderate-income people are not driving the nation’s long-term fiscal problems. Spending on low-income entitlements did rise markedly in response to the Great Recession and slow recovery. But federal spending for low-income entitlement programs outside of health care has fallen significantly in the past few years as a share of gross domestic product (GDP). And under current law, spending for low-income entitlement programs outside of health care — which provide basic assistance to impoverished and near-poor families and individuals — is projected to fall by 2020 back to its average level as a share of GDP of the past 40 years (just 1.3 percent) and then fall below the 40-year average after that.[1] (See Figure 1.)

The nation’s long-term fiscal challenge is that the federal debt is projected to grow faster than the economy for many years to come. But programs, or sets of programs, that won’t grow faster than the economy don’t contribute to our long-term fiscal problem, and policymakers needn’t cut them for fiscal reasons. Nor should policymakers cut these programs to finance big tax cuts that would go overwhelmingly to those at the top or big defense increases, which, if needed, should be financed in ways that do not ask only low-income families to shoulder the costs. It is worth noting that federal assistance for those in need is already stingier than that provided by most other Western governments.

To be sure, Medicaid is slated to grow faster than the economy. But as with Medicare, that’s due overwhelmingly to two factors: (1) the aging of the population, which will make more seniors — who have much higher average health care costs than younger people — eligible for coverage; and (2) rising costs throughout the entire U.S. health care system, which reflect, in part, medical advances that improve health and save lives but add to costs. Medicaid actually costs substantially less per beneficiary than private insurance or Medicare, and Medicaid costs per beneficiary have been rising more slowly in recent years than those for other insurance. Medicaid is the nation’s most economical form of large-scale health insurance.

Moreover, the Congressional Budget Office projects that over the coming decade, the rise in spending under current law in Medicaid and other low-income health programs (as a percent of GDP), will be fully offset by the projected decline in other low-income programs, including both low-income entitlements and discretionary programs. Overall spending on low-income programs — health and non-health combined — is expected to be 4.7 percent of GDP in 2017, falling slightly to 4.6 percent in 2027.

Cutting Assistance for Families in Need Isn’t “Welfare Reform”

Those proposing to cut low-income assistance programs by hundreds of billions of dollars over the next decade often portray their proposals as “welfare reform.” That label, however, is misleading.

Consider President Trump’s budget proposal for $272 billion in cuts to low-income entitlements other than Medicaid, which his budget presents as “welfare reform.” The large majority of those cuts — $193 billion — would come from SNAP, even though SNAP benefits average only $1.40 per person per meal and go overwhelmingly to households with incomes below the poverty line.

To generate those savings, the President proposes to cut SNAP benefits directly for millions of low-income families and individuals and then to require states to start paying an average of 25 percent of SNAP benefit costs while letting states slash benefit levels further to ease the fiscal burdens this cost-shift would impose on them. Such proposals ignore the strong evidence of SNAP’s effectiveness. While benefits are modest, the food assistance that SNAP provides lifts 8 million people, including 4 million children, out of poverty, and brings another 26 million people closer to the poverty line. And research has found that children who participate in SNAP have improved longer-term educational attainment, health, and economic outcomes.

Proposals to cut SNAP despite this evidence would take food off the table for millions of low-income children, seniors, people with serious disabilities, and low-wage working parents — and push them into, or deeper into, poverty. These proposals also would squeeze state budgets.

While labeling cuts in SNAP and other areas as “welfare reform,” the Administration argues that they’ll entice more people to get jobs. But the President isn’t proposing to expand or improve access to the job training or child care that low-wage working parents need to work or attend job training; to the contrary, he’s proposing to cut such programs. Also, the SNAP cuts would affect families that are already working and receive this basic food aid to supplement their low wages.

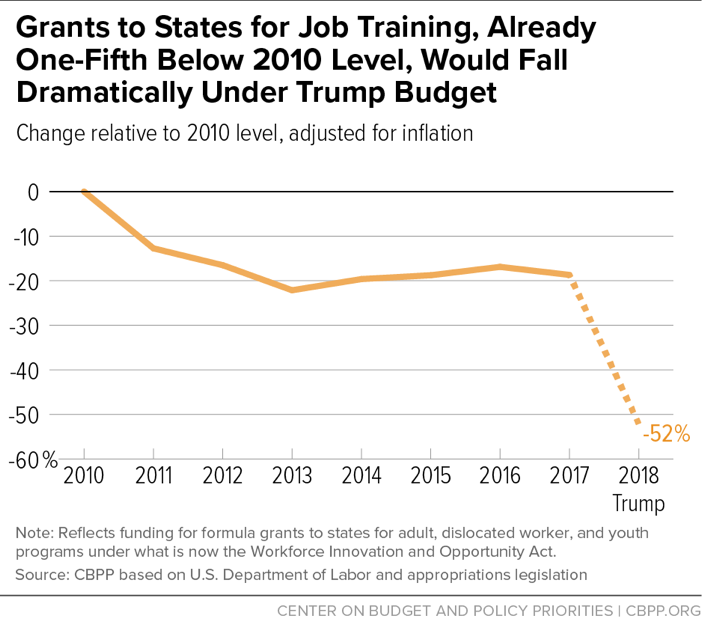

The Freedom Caucus’ current and former chairmen, Reps. Mark Meadows and Jim Jordan, respectively, have called for deep cuts in SNAP, TANF, and housing programs that they, too, have labeled “welfare reform.” They have introduced legislation, along with Senators Ted Cruz and Mike Lee, that would impose unfunded and largely unworkable requirements to force states to create new work programs in SNAP and TANF. The requirements would consist of rigid rules that don’t account for the research in the field on the employment barriers that many jobless individuals face and what can be most effective in overcoming them. Their bill also provides no new funding for the job training, subsidized jobs, or the child care that some families would need; instead, it encourages states to raid job training resources for other workers. That’s particularly problematic given that policymakers have cut the core job training grants to states by 20 percent since 2010, after adjusting for inflation, and President Trump proposed in his budget to cut them another 40 percent in 2018. (See Figure 2.)

The SNAP and TANF savings under this bill would almost certainly come mainly from (1) large financial penalties on states that couldn’t meet the unrealistic, overly prescriptive, and likely administratively infeasible work requirements that the bill would impose on states, and (2) the denial of assistance to large numbers of impoverished families and children when a parent or other individual is judged non-compliant with rigid requirements that are often ill-suited for the parent and not what he or she needs to succeed in the workplace.

The bill also would eliminate nearly all major federal housing assistance programs for low-income families and replace them with block grants to states that would have sharply reduced funding — and wouldn’t even have to be used for low-income housing. There is no rationale provided or pretense of reform; this is simply a massive cut to housing assistance that helps many impoverished and near-poor seniors, people with disabilities, and families — including many working-poor families with children — afford a roof over their heads.

Under such approaches, most poor adults wouldn’t get the help they need to secure and hold jobs. And they and their children could be left without basic food, cash, and housing assistance that are critical to their well-being — especially in the case of young children, whose brain development and long-term prospects can be adversely affected by the living conditions associated with severe poverty.

Commentary: House Moving to Fast-Track Both Low-Income Program Cuts and Tax Cuts for Wealthy

End Notes

[1] For more information on the trends in spending for low-income programs, see Robert Greenstein, Richard Kogan, and Isaac Shapiro, “Low-Income Programs Not Driving Nation’s Long-Term Fiscal Problem,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated February 21, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/research/long-term-fiscal-challenges/low-income-programs-not-driving-nations-long-term-fiscal. See also, Isaac Shapiro, “The Myth of the Exploding Safety Net,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 22, 2017, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/the-myth-of-the-exploding-safety-net-0.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise

Recent Work: