Just weeks after enacting very large tax cuts heavily tilted toward wealthy households and large corporations, President Trump unveiled his fiscal year 2019 budget, which deeply cuts low-income programs like SNAP (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly food stamps), Medicaid, and housing assistance that help struggling families afford the basics.[1] The Administration’s budget includes a number of proposals it claims will help struggling, out-of-work people build skills and succeed in the labor market. But on the whole, the proposals in this budget would hurt struggling working families and make it harder — not easier — for those who need skills to establish a career and get ahead.

The Administration’s budget fails to invest in core job training programs, sets these programs up for likely deep cuts in future years, and proposes cuts in a range of other programs supporting work and opportunity. The budget’s principal goal in this area appears to be to make large cuts in these areas, not to help those whom the economy has left behind.

A plan to actually increase employment and earnings among jobless or underemployed workers with low skills would include: substantial new investments in high-quality job training; broad efforts to make college more affordable; subsidized jobs for those who need to build work experience and skills; and adequate investments in child care so parents can work or participate in training or education programs. But the President’s budget includes none of these, except for a very modest increase in funding for apprenticeship. To the contrary, it freezes funding for core job training for 2019; calls for deep cuts in future years in the part of the budget that funds job training, child care, and Pell Grants; includes proposals that would make college more expensive; and targets working families for cuts in assistance that help them afford the basics, and in some cases, even reduces work incentives in existing program eligibility rules.[2]

Taken together, these proposals will make it significantly harder for people left behind by the economy to move up the economic ladder.

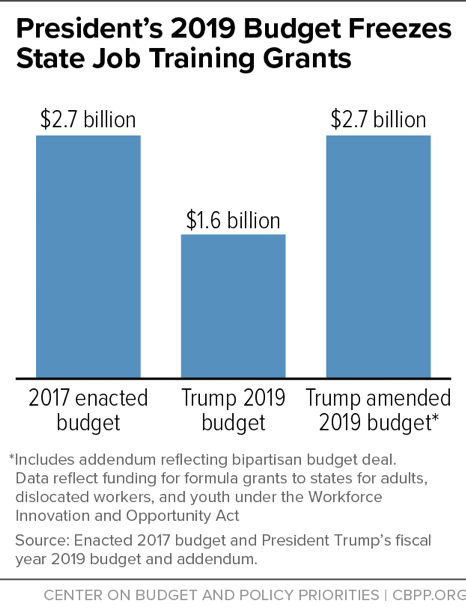

The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) provides funding to states and communities for job training for adults, dislocated workers (generally those who have recently lost jobs due to layoffs or those who receive or have exhausted unemployment insurance benefits), and young people (with an emphasis on youth who are neither in school nor working). The Administration is proposing to freeze these grants at the 2017 level of $2.7 billion, which means the grants would be worth less in 2019 than in 2017 due to inflation. The President’s 2019 “base budget” — that is, the budget that went to print before Congress and the Administration reached a budget agreement for 2018 and 2019 in February, just before the President's budget was released — would have cut WIOA job training grants by 40 percent (see Figure 1). When the Administration released its budget, it also released an “addendum” that showed areas where it was requesting additional funding in light of the budget agreement; the addendum brings job training funding back to 2017 levels, but provides no new investment, nor even adjustments for inflation.

Job training funding has been falling for a number of years, in large part because of the tight caps that the 2011 Budget Control Act and sequestration placed on non-defense discretionary (NDD) programs. Under the Administration’s budget (taking the addendum into account), funding for WIOA job training grants in 2019 would be 22 percent less than its 2010 level, after adjusting for inflation.

In addition, funding for job training would likely fall substantially in years after 2019 under the President’s budget plan. That’s because the budget calls for sharp cuts in NDD funding after 2019 — under the plan, overall funding for NDD programs in 2028 would be 42 percent below the 2017 level, and 50 percent below the 2010 level, adjusted for inflation.[3] That job training was targeted for such deep cuts in the Administration’s base budget strongly suggests that it would be targeted for deep cuts in future years when the Administration likely again calls for drastic reductions in overall funding for NDD programs.

The President’s budget also cuts Job Corps by a fourth and cuts another $531.9 million in funding by eliminating three programs that target groups facing unique barriers to work: the Indian and Native American national programs,[4] the Senior Community Service Employment program, and the Migrant and Seasonal Farm Worker program. To be sure, there might be reasons to reduce funding in some areas to invest more in others. But the proposed cuts in training programs overall mean that investing in skills is not a priority for the Administration.[5]

The budget does include some modest new investments in 2019, though many of these could be in jeopardy after 2019 if the Administration’s proposal for sharp NDD cuts in later years were ultimately adopted. For example, the budget increases funding for apprenticeship programs to $200 million in 2019, up from $95 million in 2017. Apprenticeship programs are important and should be expanded, but they’re just one part of a workforce development strategy (they constitute just 6 percent of the Labor Department’s training and employment services budget in the President’s proposal). The budget also provides an additional $15 million compared to 2017 for reemployment services and for eligibility assessments for certain unemployment insurance recipients, and calls for a larger investment in these services in future years.

The budget also cuts the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant and eliminates altogether the related TANF Contingency Fund — a cut of $2.3 billion, or 13 percent, compared to current law. States use TANF funds for short-term income assistance and other crucial supports for struggling families with children, including employment services and job training. The budget would also require states to focus a larger share of their TANF funding on work programs, education and training, and child care. While focusing a larger share of TANF on certain activities that support work is a sound idea, this proposal is problematic both because the 10 percent funding cut will undercut the benefit of increased targeting of resources and because the plan fails to recognize that providing income assistance to families that are very poor is also crucial to helping them regain their economic footing.

The 2019 Trump budget eliminates the Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant (SEOG), which supplements Pell Grants for some of the neediest students. The justification is that SEOG funds are not optimally distributed across schools. But rather than change the funding allocation, the Administration wants to eliminate a program that makes college more affordable for 1.5 million of the neediest students in the country — with no replacement.

The budget also deeply cuts the work-study program (even taking into account the budget addendum). It justifies the cut by saying that the Administration wants to change the type of work opportunities available to students, but slashing funding would leave fewer students with job opportunities of any kind to help pay for college.

In addition, the budget includes a series of changes in the student loan program that would raise students’ borrowing costs. Some of the reforms have merit, such as consolidating loan repayment options. But the changes overall would make college less, not more, affordable. The budget cuts student loans by more than $200 billion over the next decade and fails to meaningfully invest these funds into expanding college affordability. Indeed, the budget freezes Pell Grants, which means their value would erode with inflation and they would do less each year to help low- and moderate-income students afford college.

Finally, the budget calls for allowing students to use Pell Grants to pay for certain short-term programs that provide students with a credential, certification, or license for in-demand jobs. Whether this is a positive step depends on whether the programs that are made Pell-eligible deliver high-quality education. And there are reasons for concern here. While the Administration has indicated that only “high-quality” short-term programs would be eligible for Pell, details about how quality would be assessed has not been released. Moreover, the Administration has taken a number of steps to roll back accountability measures in higher education that previous administrations put in place to crack down on poor quality and the unscrupulous behavior of some colleges, particularly for-profit colleges.[6]

Subsidized jobs can be used to help those who cannot find work and need help building skills or work experience. They also have a strong track record of providing an opportunity for those who can’t otherwise find a job to work and earn money to meet their basic needs.[7] During the Great Recession, states used funds from the TANF Emergency Fund to create 260,000 jobs, which helped low-income parents and youth who couldn’t otherwise find jobs gain work experience and earn money they could use to pay rent and put food on the table. Outside of recessions, subsidized jobs can be used to help those unable to find jobs either because of localized high unemployment or because individual workers have too few skills to obtain employment in their local job market. The President’s budget has no specific proposals to create jobs for those who want them but can’t find them.

Child care is key to helping parents work when their earnings are too low to afford the high cost of care — and also is central to low-income parents’ ability to engage in job training or go to school. Due to inadequate funding, today just 1 in 6 children who qualify for child care assistance (because their caretakers have low or moderate incomes) receive it.

Even though millions of children in struggling working families receive no child care assistance, the budget provides funding for the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) at just $150 million above the 2017 level. Moreover, even though the budget addendum was designed to reflect the budget agreement Congress had just reached, it failed to incorporate the agreement’s explicit commitment to double CCDBG funding to $5.8 billion in 2019 — funds needed both to help states meet the new quality standards Congress set in the bipartisan 2014 child care reauthorization legislation and to expand access to more children and their families.[8] Again, because the budget calls for sharp cuts in NDD funding after 2019, it would likely mean that investments in CCDBG would fall substantially in years after 2019 under the budget plan.

Proposed cuts in SNAP, housing assistance, and Medicaid would make it harder for millions of families to afford food and rent and leave millions of Americans without health insurance — likely leading to food insecurity, housing instability, and worse health outcomes that would make it harder for many working families to stay employed and make ends meet.[9] The budget would also enact policy changes that could reduce work incentives already built into program eligibility rules:

- In SNAP, a state option allows working families to continue to receive benefits that phase down gradually — falling by about 30 cents for every additional dollar earned — if a family’s income rises modestly above the typical cut-off at 130 percent of the poverty line ($27,000 per year for a family of three). The President's budget would reinstate a benefit cliff by eliminating this option, forcing states to terminate modest but important benefits to working families whose income rises modestly above 130 percent of the poverty line.

- The budget proposes raising from 30 to 35 percent the share of income that households receiving federal rental assistance must pay in rent. The bulk of such rent increases would fall on low-wage workers, whose rent payments would rise by close to $120 a month, on average. Such families typically have little or no room in their budgets to cover added costs after paying for other basic needs and work expenses like child care and transportation. The budget would also eliminate entirely the current income deduction for child care expenses, which would further raise rents on many working families receiving housing aid and make it more difficult for them to work. These families’ rents would rise from 30 percent of their incomes after deducting child care costs to 35 percent of gross income with no deduction for child care costs.

-

The Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion currently allows adults (in states that adopted the expansion) to remain eligible for Medicaid until their incomes reach 138 percent of the poverty line ($16,800 for a single person or $28,700 for a family of three in 2018), at which point they can receive premium tax credits (phasing down as income rises) to purchase private insurance coverage in the marketplace. In contrast, prior to the Medicaid expansion, working parents often lost Medicaid coverage if their earnings rose above a certain level that, in most states, was below the poverty line.[10] (This remains the case in non-expansion states.) Meanwhile, low-income adults without children, including many working people, were usually ineligible for Medicaid regardless of how low their incomes were.

The Administration’s budget embraces the ACA repeal bill sponsored by Senators Bill Cassidy, Lindsey Graham, Dean Heller, and Ron Johnson, then cuts funding for health coverage programs well below the already shrunken levels in that bill. The budget would eliminate the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and marketplace subsidies, replacing them with an inadequate block grant. Block grant funding would be well below current-law federal funding for coverage. The proposal also would impose a “per capita cap” on federal Medicaid funding for seniors, people with disabilities, and families with children. Such a cap means that the federal government would only pay a certain amount for care per person, regardless of the actual cost of care. And, the proposal sets the per capita cap at a level that is below expected health care costs, with the shortfall growing each year.

With cuts this deep, the Medicaid expansion would be likely to end in many states; there would be no requirement for states to offer coverage or financial assistance to the people whom the expansion now covers. That could cause millions of vulnerable people — including many low-income workers whose employers don’t offer coverage — to lose Medicaid and become uninsured. Taking away health coverage would likely impede work for many people: studies of Medicaid expansion enrollees in Ohio and Michigan find that majorities say gaining coverage has helped them look for work or keep their jobs.[11] It could also reinstate income “cliffs” where working parents lose their health coverage if they increase their hours or get a better job.

The budget calls for testing new approaches to increasing employment among people with disabilities and then assumes large savings will result, largely from reduced payments of Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). But evidence shows that given the age and impairments of those receiving these benefits — and their high death rates — large savings from substantial employment increases are unlikely.[12] The budget also cuts in half the retroactive benefits that workers with a disability may receive. These are benefits provided to new SSDI recipients to reflect the loss of earnings over the time between when they became disabled and the time they applied for disability benefits. Sometimes people delay applying for disability benefits after the onset of their disability as they hope and try to get better and go back to work.

The Trump Administration claims it’s attempting to aid those facing difficulties in today’s economy and to help more people work. But its own budget fails to fund — and in many cases cuts — the very investments that can help people find family-sustaining employment, stay on the job, and climb the economic ladder.