Unemployment benefits provide critical support to jobless workers, their families and communities, and the U.S. economy. Yet today, the UI system is alarmingly unprepared for the next recession. Permanent reform is needed to ensure the UI system works for all workers at all times, but if a near-term economic downturn occurs, Congress must be prepared to enact emergency measures to address the most significant deficiencies in the current system.

The UI system is a federal and state partnership designed to serve two interlaced purposes: (1) provide economic support to workers and their families to ensure they can afford necessities while they search for new employment that best matches their skills; and (2) steady the overall economy during economic downturns by sustaining consumer demand.

Providing economic support to jobless workers is particularly important for workers of color. Due to systemic racism in the labor market, Black workers, in particular, have higher unemployment rates and face longer periods of unemployment.[1] As a result of historic exclusions from wealth building opportunities, workers of color are also less likely to have sufficient savings to weather periods of unemployment.[2] Unfortunately, the current UI system excludes many more unemployed workers than it covers, with Black workers, other workers of color, and women facing the largest barriers to receiving benefits.

During normal economic times, the failure of the UI system to reach all workers severely undercuts its intended purposes. Such a gap is amplified, however, during economic downturns, particularly the program’s ability to act as an economic stabilizer.

Even as the percentage of unemployed workers receiving UI might rise during recessions, the number of people in need of such benefits greatly increases, and therefore coverage gaps leave more jobless workers without benefits during downturns compared to normal economic conditions. Workers also often have a harder time finding jobs during recessions, so their periods of joblessness tend to be longer. As a result, Congress has stepped in to enact temporary measures designed to try to fill some of the largest gaps in the program during recessions, including addressing low benefit amounts and the number of weeks people can receive benefits.[3]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Congress continued this tradition and also expanded eligibility to workers who usually do not qualify for UI, including app-based workers who are misclassified as independent contractors,[4] self-employed workers, and some part-time workers. This expansion substantially expanded coverage with roughly 1 in 6 U.S. adults (about 40 million people) receiving UI at the height of the pandemic.[5] Increased benefit amounts also ensured unemployed workers could afford necessities, such as rent and food, helping to keep families above the poverty line and to sustain spending at local businesses.[6]

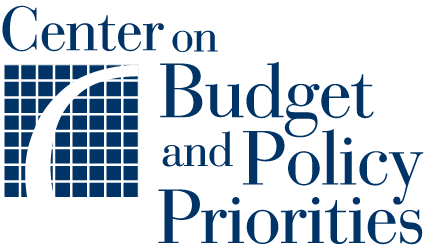

However, since Congress let the programs expire in September 2021, the proportion of unemployed workers receiving unemployment insurance — known as the recipiency rate — has returned to the pre-pandemic level of about 25 percent, and even many of those unemployed workers who are able to get benefits struggle to survive on the meager amounts.

Congress must begin to address the long-standing systemic issues in the program that shut far too many workers out.[7] Should the economy decline, long-standing problems with the system, as well as continuing impacts from the recent pandemic-induced downturn, would leave millions of workers who lose their jobs with nowhere to turn.

Restrictive and outdated eligibility requirements prevent far too many jobless workers from getting any UI benefits, while significant limits on the duration and weekly benefit amount substantially reduce UI’s impact for those who do receive benefits. These impacts are significantly heightened during an economic downturn, when more people lose their jobs and are out of work for longer periods — requiring more to need assistance and to need it for longer than most or all states provide.

Over the roughly 60 years preceding the pandemic, the share of all unemployed workers receiving UI benefits slowly fell from approximately 50 percent to less than 30 percent. The failure of the UI system to adapt to a changing economy over these decades — leaving out independent contractors, self-employed workers, and many part-time workers — as well as state legislators’ deliberate policy choices to restrict access to unemployment benefits in some states, led to this drop in coverage.

While the UI recipiency rate often rises somewhat during recessions, even then the program’s reach remains severely limited. Since 1975, annual UI recipiency hasn’t come close to reaching 50 percent until Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) was temporarily established in 2020 to expand UI coverage to workers who are usually excluded.[8]

As with many features of the UI system, recipiency rates vary significantly among states depending on the policy choices they make. In 2022, 14 states had UI recipiency rates below 15 percent. (See Figure 1.)

The inadequacy of UI coverage for jobless workers stems from a multitude of factors, including exclusions for certain types of workers, such as self-employed or independent contractors, barriers to coverage for low-income and part-time workers, requirements for program eligibility, ease and accessibility of the UI application, and limits on the length of time an individual is permitted to receive benefits.

Workers of color are disproportionately impacted by many of these coverage impediments given their over-representation in certain underpaid or precarious occupations, and factors such as language barriers for some workers who are immigrants and longer average duration of unemployment for Black workers. Moreover, Black workers disproportionately live in the states with the most restrictive state laws and lowest UI recipiency rates — another key reason for their overall diminished access to unemployment benefits.

In short, many people losing work are excluded from the regular UI system, and without federal intervention the number of workers left out will grow substantially during the next recession.

Recognizing that regular unemployment benefits do not continue long enough to adequately assist those looking for new work in a depressed job market, Congress has acted in nearly every recession over the past 70 years to temporarily extend the duration of unemployment benefits. While the timing, duration, and amount of assistance provided by these programs differed, all were enacted to help workers continue their job searches without being forced into destitution, while also buttressing consumer demand and the broader economy.[9]

Until 2009, every state provided a maximum regular UI benefit of at least 26 weeks during all economic circumstances. Policymakers in ten states cut the number of weeks after the Great Recession of 2007-2009, and three additional states (Kentucky, Iowa, and Oklahoma) reduced UI duration after the recent pandemic-induced recession.[10] Some of these states have simply reduced the maximum available duration of UI to less than 26 weeks, others have reduced weeks conditionally based on their state’s unemployment rate or some related factor, and some have enacted cuts based on a hybrid of these two models.

Without federal intervention, any future recession will have a particularly harmful impact in the 13 states where policymakers have cut maximum UI benefit duration. Even in the states that have set up their system so duration rises with the state unemployment rate, benefit durations will be slow to rise because of the amount of increased joblessness needed for duration to rise and the significant lag times between an increase in unemployment and a rise in benefit duration. For example, in Kentucky, based on legislation passed last year, even if the state’s current unemployment rate doubled, maximum UI duration would rise to just 19 weeks, up from the current 12 weeks.

Harsh limits on benefit duration, as with other restrictions in the UI system, fall particularly hard on workers of color. Asian workers and especially Black workers have longer average durations of unemployment than white workers, stemming from systemic discrimination in the labor market and other barriers to employment.[11]

The average weekly UI benefit across the U.S. was $392 in the third quarter of 2022, replacing a little less than 40 percent of the average weekly wage. Considerable variation occurs across states, ranging from a high average weekly amount of $616 in Washington State to a low of $215 in Mississippi.[12] The average weekly UI benefit is below the 2023 poverty level for a family of one in ten states (Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Arizona, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, and Tennessee). In over three-quarters of the states, the average unemployment benefit fails to reach the poverty level for a family of three.[13]

High inflation also reduces the real value of UI benefits and makes it even harder for jobless workers to pay for food or rent. Though recent inflation data have showed some positive signs of moderating, price increases over the last year have been steep. In September, the consumer price index, which excludes food and energy costs, registered its biggest one-year increase in 40 years, and the food at home index rose by 11.4 percent in 2022.

UI payments should rise as wages grow, but only 33 states (plus Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands) set their maximum benefits as a portion of the state’s average weekly wage.[14] The remaining states have a stagnant maximum benefit amount that does not automatically grow with wages. For example, California’s maximum weekly benefit amount of $450 has not changed since 2005.

States should increase UI benefits to more adequate levels as part of broader, systemic reform. In advance of such efforts, a federal supplemental unemployment payment would help mitigate this erosion in UI purchasing power, while also improving the anti-poverty and economic stabilization effects of unemployment benefits during a future recession. Without federal action, regular UI benefits in many states will be far too low to sustain consumer demand or to keep unemployed workers and their families fed and housed during the next recession.

Remaining Effects From the Pandemic Recession Raise Additional Concerns

Unemployment insurance was a lifeline for tens of millions of workers during the pandemic, especially the temporary federal programs that expanded eligibility, increased weekly benefit amounts and lengthened duration. But the pandemic also exposed the long-standing systemic issues with the system that exacerbate racial and economic inequities and undermine its purpose and its potential to provide a strong social infrastructure.

Almost overnight, state agencies were flooded with an unprecedented surge of new UI claims as over 20 million workers were forced out of work to protect public health.[15] And this continued well into the pandemic. Every week for the first nine months of 2021, more than 10 million workers received unemployment benefits.[16]

Although state agency workers made herculean efforts to process and pay out this unprecedented surge in claims, years of administrative underfunding, outdated and neglected technology systems, and overly burdensome application processes overwhelmed state agencies.

While the U.S. is well past the peak of the pandemic-induced unemployment surges, the impact of processing so many claims while also standing up new federal programs continues to impact state agencies at all levels of claim processing. Thus, although initial claims are at historic lows, long wait times and customer service issues persist.

Federal standards require state agencies to pay at least 87 percent of initial claims within 14 days (or 21 days in states that do not have a waiting week for benefits). However, at the end of 2022, only 11 states met this standard.[17]

Similarly, the federal standards require states to resolve lower authority appeals within 30 days.[18] Yet, at the end of 2022, less than half the states and jurisdictions met this standard. In fact, the national average wait time to receive a decision on a lower authority appeal at the end of 2022 was 201 days, with workers in five states (Alabama, Arizona, Louisiana, Nevada, and Virginia) waiting, on average, over a year.[19] These wait times have risen sharply since the pandemic. At the end of 2019, nearly every state met the federal appeals standard, and the national average wait time was only 25 days.[20]

Furthermore, state agencies are still working through a host of other problems left over from the pandemic, including reevaluating claimant eligibility for pandemic-era programs and identifying and processing overpayments and waivers.

In addition, many state agencies are restarting technology modernization projects they put on hold during the pandemic. Based on our work with advocates across the states, we know that at least one-third of the states are now or are about to start modernizing their technology systems. This work is critical, as outdated technology hampered agencies’ ability to implement the federal pandemic programs, ensure timely payments, and protect program integrity during the pandemic. It is true, however, that such projects further burden already under-resourced agencies and staffs.

Indeed, the root cause of many of the administrative problems during the pandemic, which persist today, is the lack of consistent and sustainable administrative funding for state agencies. Federal funding to states for UI administration has generally remained flat or declined for the better part of the last four decades,[21] leaving these agencies woefully understaffed and resourced heading into the pandemic.

While Congress increased administrative funding last year, that was insufficient to remedy years of disinvestment and underfunding of the system at both the state and federal levels. States need consistent, sustainable funding so they can invest in long-term projects and staff to be ready for the next recession. The Department of Labor (DOL) and its regional offices that assist state agencies and oversee the UI system must also be sufficiently staffed and resourced.

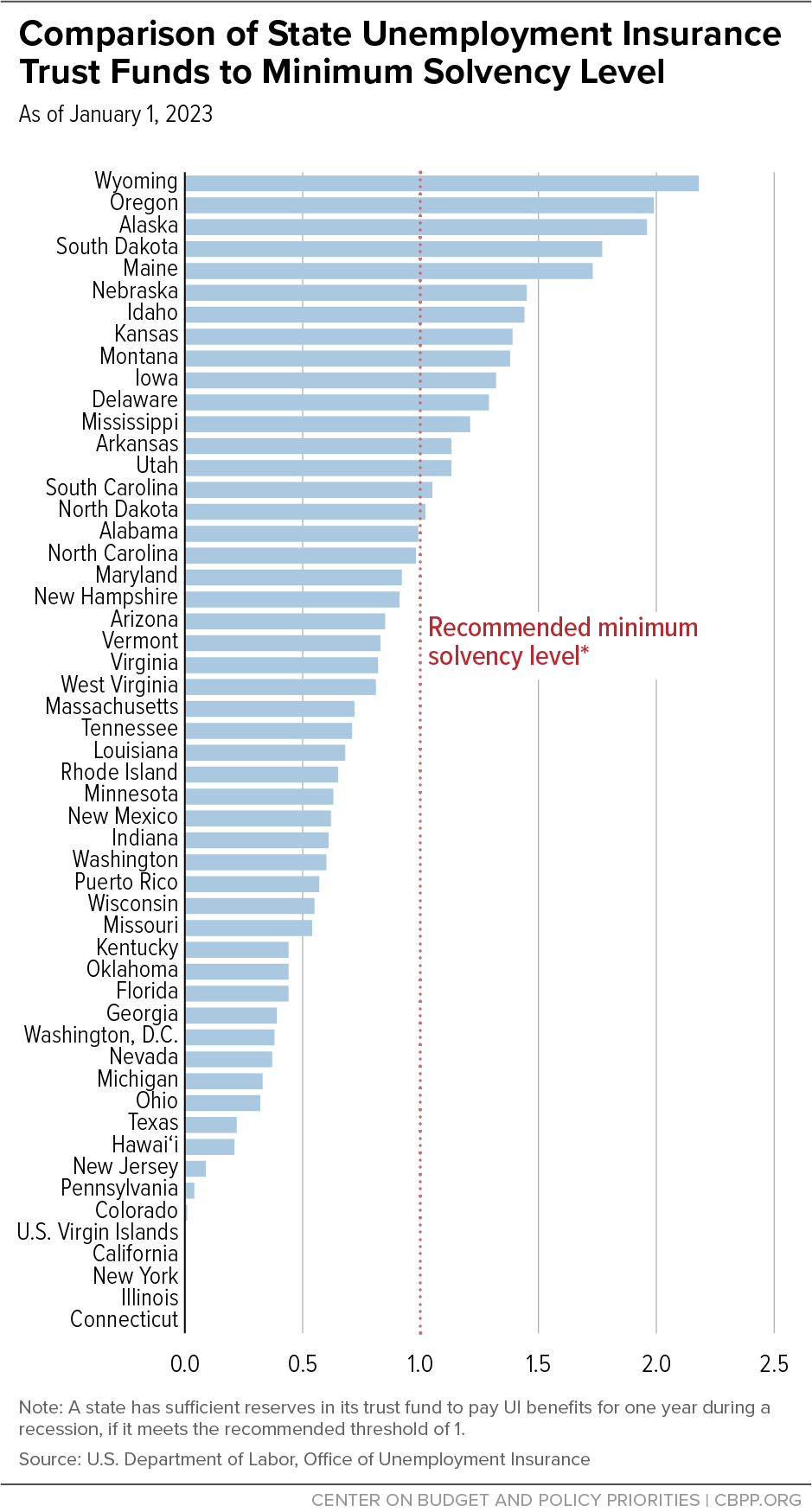

The pandemic also deeply impacted the solvency of state unemployment insurance trust funds. Under the current federal-state structure, employers pay both a state and federal payroll tax on their employees’ behalf to fund the UI system. State taxes are deposited in a UI trust fund that is used to pay out benefits. Under federal guidance, states are supposed to create a tax structure that ensures trust funds are sufficient to pay out at least a year of recession-level benefits.

However, many states do not meet this standard even in non-recessionary times — and it is even worse after a recession. At the beginning of 2020, 31 states met the minimum solvency standard of being able to pay out a year of recession-level benefits.[22] As of January 2023, that number had fallen to only 16 states.[23] (See Figure 2.) Four states and the U.S. Virgin Islands also have remaining trust fund loan balances from needing to borrow money during the pandemic to continue to pay benefits.[24]

While some states have been able to replenish their state UI trust funds in the short term by using federal pandemic relief funds allocated through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act or the American Rescue Plan Act, this did nothing to address the long-term systemic issues that led to trust fund underfunding and insolvency. In fact, as noted above, states already have moved to cut benefits, rather than to reform the UI tax structure to improve trust fund solvency. That will leave the state UI systems even more insufficient to meet worker needs when we enter the next recession.

Lessons Learned From Pandemic Unemployment Programs

Temporary Pandemic Relief Programs Boosted UI

The CARES Act, passed on a bipartisan basis and signed into law by President Trump on March 27, 2020, established the primary unemployment benefit programs designed to respond to the enormous rise in joblessness due to COVID-19. These programs, which were extended and modified by several subsequent measures, including the Rescue Plan, signed into law by President Biden, and which expired in early September 2021 (with some states terminating the programs earlier) included:

Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC). Supplemented weekly UI benefits by $600 until the program expired on July 25, 2020. Reestablished as a $300 weekly supplement between December 26, 2020, and September 4, 2021.

Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA). Provided benefits to individuals unemployed due to a specific COVID-related reason and not otherwise eligible for regular state-provided UI benefits. Workers covered included those with low-wage, part-time and shorter work histories, self-employed workers, and independent contractors.

Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC). Provided additional weeks of benefits to workers who exhausted regular state-provided UI benefits. The program ultimately allowed a cumulative total of 49 weeks of additional benefits.

These unemployment programs substantially reduced the harmful effects of the massive job losses stemming from the pandemic. The benefits prevented about 5 million people from falling below the poverty line in 2020 with especially notable impacts for Black and Latinx workers and their families; significantly lessened food insecurity, rent and mortgage delinquencies, and other hardships; and reduced racial inequities in the UI system.[25]

Additionally, by supporting consumer demand, the programs helped stabilize an economy in free fall after 22 million jobs were lost in early 2020. And despite rhetoric to the contrary, the “expansion in UI had limited effects on workers’ willingness to return to work, and … other factors may explain the low levels of employment observed during adverse times when UI is also expanded,” according to a review conducted by the Government Accountability Office.[26]

While any potential future programs need to be responsive and tailored to the effects of the next recession, policymakers should consider the successes of the pandemic programs and the lessons learned to ensure future programs can replicate the programs’ successes, while alleviating their administrative issues, including long delays in benefit payment, jammed phone lines, and susceptibility to fraud.

Due to efforts to reduce exposure to COVID-19, many service-sector jobs with extensive face-to-face interaction with customers or with other staff quickly vanished. Not only were there extremely limited options for reemployment for individuals losing these jobs, in some cases government policies to protect public health required leaving these positions vacant. In this situation, the early benefit amount of $600 in the FPUC program was justified, especially given concerns about how a rapid loss of so many jobs and the corresponding reduction in consumer demand would impact the overall economy.

In a more typical recession, it will still be essential to supplement benefits given the low benefit amounts in many states, particularly those with the largest Black populations. Supplemental benefits should be high enough to address the inadequacies of regular UI payments, both to reduce hardship caused by a downturn and to support economic stabilization by buttressing consumer demand, without being so high as to significantly exceed most individuals’ prior wages.

An individualized supplement that would prohibit any worker’s overall benefit amount from exceeding their prior wages would be the best way to achieve these goals. But administrative limitations within most, if not all, states’ UI systems hamper them from being able to implement such an approach, necessitating the use of another federal flat rate supplemental amount if we enter another recession before permanent reforms can be enacted.

In this context, implementing a $300 supplement similar to the amount paid by FPUC when the program was reestablished is worth considering. Based on research by economist Peter Ganong and colleagues, with a $300 supplement, a majority (52 percent) of workers’ total benefit amount (regular UI and federal supplement) would be equal to or less than their prior wages.[27] An additional 21 percent would receive only slightly more (100 to120 percent) than their prior wages.

Those workers who may receive more than their prior wages are most likely to be the lowest-paid workers who already depend on their entire paycheck to pay for food and rent and have the least savings to fall back on during a period of unemployment. Moreover, these data consider only lost wages and not other lost compensation, such as employer-provided health benefits, retirement contributions, and paid leave — payments that fall directly on workers during job loss. Some workers who may receive more in benefits than their prior wages may therefore still be worse off in real terms.

Expanded Coverage

As previously discussed, only about one-quarter of unemployed workers currently receive regular UI benefits under the current system. Although that percentage may climb modestly during a recession, it is unlikely to come close to even a 50 percent recipiency rate because of restrictive state eligibility rules. Without a temporary federal expansion, many millions of those losing work in a recession would be excluded from coverage, as indicated by the fact that at the end of 2020, roughly 8 million unemployment claims were being paid under the PUA program compared to only about 5 million under regular UI.

For a typical recession that the U.S. might experience in the future, the PUA eligibility rules that required workers to have lost their jobs as a result of COVID-19 would not be relevant. An alternative standard could make workers who lose their jobs after a certain date related to the recession eligible for expanded coverage under a temporary federal program if they are not eligible for regular UI. This would be similar to Disaster Unemployment Assistance, which is tied to the date of a declared major disaster. To streamline the administration of such an alternative unemployment compensation (AUC) program, the program could provide a simple, flat benefit amount that is either consistent across the states or is based on each state’s average weekly regular UI benefit amount.

Improved safeguards against identity theft must be implemented for any temporary AUC program. Better security will enable states to avoid repeating the experience of the PUA program, which was targeted by criminal organizations that used stolen identities to obtain fraudulent payments. Beyond the specific steps recommended below, the recent work of states and the DOL to address this concern within the expired pandemic unemployment programs will provide a much-improved starting point compared to those programs, which had to be implemented rapidly. For example, DOL has put many initiatives in place to reduce UI fraud, including sending “tiger teams” of experts to states to improve program integrity and equity, helping states expand data matches for UI applicants, and working with states to improve identity verification procedures.[28]

As eventually required in the PUA program in early 2021, workers would need to provide proper documentation to demonstrate prior work.[29] This provides additional protection against criminal syndicates using stolen identities to claim UI benefits.

States also would have to continue to use strong identity verification procedures set up during the pandemic. These procedures should not erect unnecessary or unfair barriers to eligible claimants (concerns have arisen, for example, about facial recognition technology disproportionately flagging workers of color for undue attention). Rather, states must continue to balance equitable access with program integrity. And claims should be cross-matched with other public data sets, including those for individuals who are incarcerated, using verified, up-to-date information.

To continue progress in modernizing UI administrative systems to increase access and reduce fraud, sufficient funding also must be provided on an ongoing basis.

Previous temporary extended benefits programs implemented during past recessions have taken different forms, including some that provided more benefit weeks in states with higher unemployment rates. It may be preferable to follow the simplest model, which was adopted during the pandemic, of providing an additional 13 weeks of federally funded benefits in every state initially, and then determining future needs based on ongoing economic conditions.

To provide some additional protection in higher-unemployment states, policymakers also should make it more likely that the permanent Extended Benefit (EB) program becomes active. The EB program provides additional weeks of unemployment benefits to jobless workers who have exhausted their regular UI benefits in states where the unemployment situation has worsened dramatically, but the program often fails to activate on a timely basis or turns off prematurely because of outdated and ineffective triggers. In response to the Great Recession and the recent pandemic recession, Congress encouraged states to temporarily adopt more responsive triggers, supported with 100 percent federal funding, to make it more likely the EB program became active and stayed on long enough to address high levels of unemployment.

Beyond addressing these core issues of UI benefit adequacy, access, and duration, Congress should consider other reforms to help workers during a recession, including expanding access to the Short-Time Compensation (STC) program, also known as work sharing. Under the program, employers agree to a reduction of employees’ hours rather than layoffs during a downturn, and those workers receive a prorated unemployment payment to cover a portion of their lost wages. The STC program benefits both employers and employees, but current program requirements and administrative barriers limit its potential reach and impact.[30]

Without significant intervention to bolster the UI system before the next recession, the millions of workers who lose their jobs through no fault of their own when that recession hits will suffer severe economic insecurity and a broader economic recovery will be stymied. Federal and state legislators cannot continue to ignore the long-standing and ever-growing problems with our unemployment insurance system. Permanent, comprehensive reform is imperative, as outlined in the unemployment insurance reform principles included in President Biden’s 2024 budget proposal.[31] In the short term, Congress must be ready to enact emergency enhancements to ensure that UI can continue to support workers, their families, and the country’s local and national economies during a recession.