- Home

- Poverty And Inequality

- Research Note: DACA Boosts Education, Lo...

Research Note: DACA Boosts Education, Lowers Teen Births, Study Finds

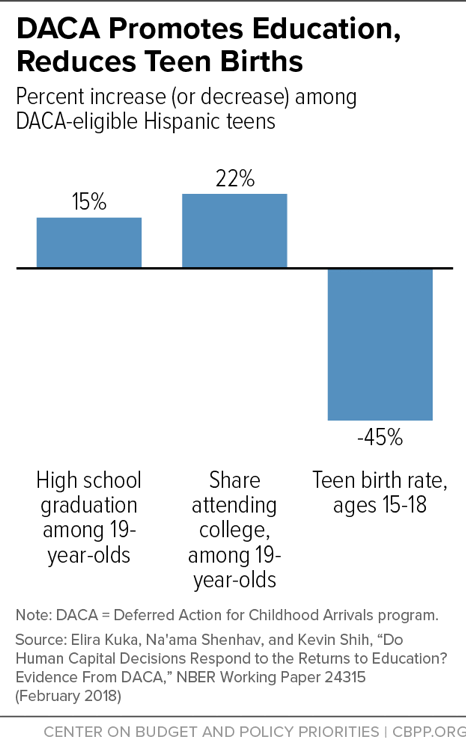

The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program provides work authorization and deferral from deportation for certain undocumented childhood immigrants, particularly those who have finished high school or are still enrolled. A new study[1] finds that DACA’s creation in 2012 coincided with striking positive effects: 15 percent more eligible Hispanic youth graduated high school, consistent with their taking advantage of DACA’s protections and opportunities for high school graduates. The study also found a 45 percent decline in teenage births and higher high school and college attendance among affected youth. Our own look at the data lends further support to these findings.

The study compares DACA-eligible groups (non-citizen immigrants who must have arrived before age 16 and before 2007, among other requirements) with otherwise-similar youths born overseas, most of whom became naturalized citizens later. It was conducted by researchers at Southern Methodist University, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and Dartmouth College.

Among DACA-eligible Hispanic youth, high school completion by age 19 rose 15 percent, the study estimates.Among DACA-eligible Hispanic youth, high school completion by age 19 rose 15 percent, the study estimates. College attendance of the same group rose by an estimated 22 percent (see Figure 1).

The education gains varied by gender. High school completion rose sharply for boys but the increase for girls was not statistically significant; the authors suggest that this might be because boys, who faced much higher deportation risk before DACA, may have been trying harder to gain DACA’s protection, which is limited to high school graduates. On the other hand, college attendance increased more for girls than boys. The authors note prior findings that girls tend to get a bigger wage bump than boys from higher education, so girls who finished high school and received work authorization from DACA may have had stronger incentives than boys to seek a college degree.

The authors also conclude that “DACA leads to lower rates of pregnancy among high-school-aged women,” noting fewer first-time births for DACA-eligible teens ages 15 to 18 and greater condom use. Reasons for such outcomes could include increased time in school or improvements in the teens’ future wage trajectory, which past studies suggest can be a powerful motivator in reducing teen pregnancy, the authors note.

The study strengthens its case by ruling out some alternate explanations for its findings, such as the possibility that the comparison group (young foreign-born citizens) was following a different trend before DACA. And the authors show their findings are not sensitive to precisely how DACA-eligible youth and their comparison group are identified.

A closer look at the data gives additional support to these conclusions. Using the same Census source the authors used (the American Community Survey), we confirmed the study’s basic conclusions; comparing the three years before and after DACA’s adoption, Hispanic teens who were eligible for DACA showed larger improvements in school attendance and high school completion and larger reductions in teen births than did the study’s comparison group (other Hispanic teens born abroad but who were citizens by the time they were surveyed).

Further strengthening our confidence in these findings, we checked whether the findings reflected various factors not explored in the paper — subtle differences between the DACA-eligible and comparison groups that the authors might not have accounted for — but found they do not. For example, the study’s DACA-eligible group and comparison group might differ in terms of parents’ education; but when we exclude the most educated households (those containing someone with a bachelor’s degree) from the analysis, the conclusion that school completion improved strongly after DACA does not change. Likewise, the study’s comparison group includes children born overseas as U.S. citizens (i.e., born in Puerto Rico or other territories or born to U.S. parents). But when we exclude them — so that the comparison group is made up purely of young immigrants who gained citizenship through naturalization, who one might expect to be more comparable to the immigrants covered by DACA — doing so makes no difference. In these and other ways, the findings of DACA’s positive effects are robust.

Ending DACA Program for Young Undocumented Immigrants Makes No Economic Sense

Consistent With Our Values, Congress Should Protect Young Undocumented Immigrants

End Notes

[1] Elira Kuka, Na’ama Shenhav, and Kevin Shih, “Do Human Capital Decisions Respond to the Returns to Education? Evidence from DACA,” NBER Working Paper No. 24315, February 2018, http://www.nber.org/papers/w24315.pdf.

More from the Authors