With President Obama and lawmakers of both parties vowing to achieve further deficit reduction, the stakes are high for low- and moderate-income Americans. If policymakers heavily target programs that serve vulnerable Americans, they will run the risk of increasing poverty and hardship and reducing opportunity for those on the lower rungs of the economic ladder, limiting their future educational and employment prospects. If, however, policymakers take a more balanced approach to deficit reduction, one that includes adequate new revenues to complement additional spending cuts, they can further reduce deficits while maintaining the resources to invest in key building blocks of future prosperity, including effective services and supports for poor families and children.

The President and Congress have already taken significant steps to reduce deficits over ten years — cutting discretionary spending by nearly $1.5 trillion and raising revenues by about $600 billion. When the resulting lower interest payments on the debt are included, policymakers have reduced deficits by $2.35 trillion over the 2013-2022 period. But, the deficit reduction debate is far from over. At a minimum, policymakers should “stabilize” the nation’s debt over the next decade so that it stops growing as a share of the economy and, thus, doesn’t increase the risk of economic and financial problems down the road. They could do so with another $1.5 trillion in deficit savings — $1.3 trillion in policy savings, generating $200 billion more in interest savings — but they face tough decisions about how to reach that goal (or a more ambitious one).[1]

In their plan of late 2010, the co-chairs of the President’s fiscal commission, Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson, established the guiding principle that deficit reduction efforts should not increase poverty or inequality, a principle that they have reiterated in recent weeks. The Senate’s bipartisan “Gang of Six” members adopted the principle for the plan that they issued in July 2011 based on the Simpson-Bowles proposal. In the months ahead, policymakers should adhere to this principle in their own deficit reduction efforts. In fact, previous major deficit reduction efforts — including the bipartisan packages of 1990 and 1997 and the Democrat-only package of 1993 — took steps to reduce poverty or increase access to health care even as they reduced deficits.

Whether policymakers will adhere to this principle in the coming months is an open question. Last year, House Republicans proposed deficit-reduction plans that targeted low-income programs for substantial cuts. (See Figure 1.) House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan’s 2013 budget resolution, which the House passed in April of 2012, secured more than 60 percent of its more than $5 trillion in spending cuts from low-income programs, including deep cuts in Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly called food stamps). This past December, the House passed legislation to replace the across-the-board spending cuts (“sequestration”) scheduled for 2013 with $315 billion in cuts over ten years — and 40 percentof those cuts would have come from low-income programs.

To be sure, policymakers can make some money-saving changes in programs for low- and moderate-income individuals or families without unduly burdening those populations. Proposals, for instance, that reduce the cost of prescription drugs to Medicaid can achieve savings without reducing access to care for low-income beneficiaries. (Policymakers also can achieve savings in Medicare without forcing low-income seniors to pay higher premiums, deductibles, or co-pays.) But the achievable savings through greater efficiencies in means-tested programs are modest. In particular, the largest means-tested program — Medicaid — already provides health care coverage at a substantially lower cost per beneficiary than private coverage. Deficit-reduction efforts that target particular low-income programs or categories of programs for substantial cuts will likely increase the numbers of poor and uninsured Americans and reduce opportunities for low-income children.

If deficit reduction targets programs that provide supports and foster opportunity for low-income families, the adverse effects will extend beyond just the low-income families and individuals who receive this assistance. The nation’s economic future depends in part on tapping the talents of as many Americans as possible. If we shortchange investments that would expand opportunity, the nation and our economy will be weaker than otherwise. As recent data and research show, various key federal programs both ameliorate poverty in the short run and have important positive impacts over the long run:

- Federal assistance lifts millions of people, including children, out of poverty and provides access to affordable health care. Overall, public programs lifted 40 million people out of poverty in 2011, including almost 9 million children.[2] While Social Security lifted the largest number of people overall out of poverty, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) lifted the largest number of children. Together, the EITC and Child Tax Credit (CTC) lifted 9.4 million people — including nearly 5 million children — out of poverty in 2011. Similarly, Medicaid provided access to affordable health care to more than 60 million people in 2009; due to Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), children are much less likely to be uninsured than adults. (For more on this issue, see “Assistance Programs Reduce Poverty and Number of Uninsured,” p. 3.)

- Programs like SNAP, the EITC and CTC, and Medicaid support low-income workingfamilies and promote work far more than they used to. Thirty years ago, Medicaid and SNAP largely served families that received public assistance and were not working. Moreover, for a full-time minimum wage worker, the EITC was only large enough to offset the employee share of the payroll taxes that that worker paid. Today, the EITC and CTC lift a family of four with a full-time minimum wage worker from 61 percent of the federal poverty line to 87 percent; most children who get Medicaid or CHIP are in working families; and among families with children that receive SNAP in a given month and include an adult who isn’t elderly or disabled, 87 percent worked in the prior year or will work the following year. (For more on this issue, see “Safety Net Supports Working Families and Promotes Work,” p. 5.)

-

Researchers have identified long-term payoffs to programs like SNAP, EITC, early education, and Pell Grants. Income supports like the EITC and CTC not only boost employment rates among parents but, research indicates, also have long-term positive impacts on children, including better school performance, that can later translate into higher earnings. Similarly, a recent study that examined what happened in the 1960s and 1970s — when government first introduced food stamps county by county — found that children born to poor women who had access to food stamps grew up with better health outcomes. Housing assistance programs eliminate several important risk factors to children failing in school by reducing the number of moves and school transitions that a child undergoes and reducing homelessness among children. Pell Grants reduce the likelihood that low-income students will drop out of college. Long-term studies that followed children who participated in Head Start have found that it raises school completion rates and improves other outcomes years later. (For more on this issue, see “Programs Improve Long-Term Outcomes, Particularly for Children,” p. 9.)

The longer-term gains that children experience from such programs may relate to recent research findings that children living in poverty can face increased intense stress that has physiological effects that impede their ability to learn and do well in school. This may help to explain why emerging research finds that significantly increasing the incomes of poor families, through measures like the EITC, produces gains in educational attainment and test scores — outcomes that, in turn, are associated with increased earnings and employment when the children reach adulthood. (For more on this issue, see the box, “Emerging Research on Connections Among Poverty, High Levels of Stress, and Child Outcomes,” p. 14.)

Assistance Programs Reduce Poverty and Number of Uninsured

Census data show that, as a group, programs that help families struggling to afford the basics are effective at substantially reducing the number of poor and uninsured Americans.

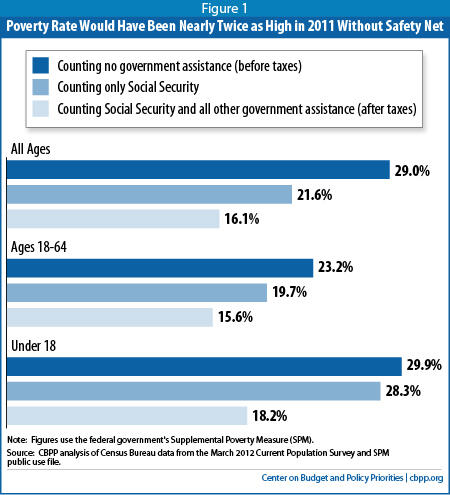

Taken together, federal benefits kept 40 million people above the poverty line in 2011, including 8.7 million children, according to the Census Bureau’s new Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM). (Among its differences from the official poverty measure, the SPM counts non-cash benefits such as SNAP and housing assistance as income, and considers the net effect of taxes — including both taxes paid and refundable credits received — on income, when determining whether a family or individual’s income is below the poverty line. The “official” poverty measure considers only cash income and ignores the role of taxes.)

Social Security had the largest effect on poverty — keeping 26 million people above the poverty line, including 16 million seniors. But other key programs keep millions of Americans out of poverty as well.

-

The EITC lifts more children out of poverty than any other program (and is the most effective program other than Social Security at lifting people out of poverty overall). The EITC kept 6.1 million Americans, including 3.1 million children, out of poverty in 2011. As noted above, the EITC and CTC together kept 9.4 million people — including nearly 5 million children — out of poverty.

- SNAP kept 4.7 million Americans, including 2.1 million children, out of poverty in 2011, and is particularly effective at keeping children out of severe poverty — that is, below half of the poverty line. In 2011, SNAP lifted more children — 1.5 million — above half of the poverty line than any other program.

- Unemployment insurance (UI) payments have been especially important in the current weak economy. UI kept 3.5 million Americans above the poverty line in 2011, including nearly 1 million children.

Medicaid and CHIP provided health insurance to 63 million Americans during 2009 — roughly 31 million children, 16.5 million parents, 9 million people with disabilities, and 6 million seniors. Medicaid and CHIP have greatly reduced the numbers of uninsured children, providing coverage to almost all low-income children. Due to Medicaid and CHIP, children are much less likely than non-elderly adults to be uninsured. Some 9.4 percent of children were uninsured in 2011, compared to 21.2 percent of non-elderly adults.[3]

To be sure, critics question the effects of safety net programs on individual behavior, such as work effort, and how that affects poverty. Some leading researchers in the field have conducted a comprehensive review of the available research and data on how safety net programs affect poverty, and the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) has published their results. They found that, after accounting for what the research finds to be modest overall behavioral effects, the safety net lowers the poverty rate by about 14 percentage points. In other words, one of every seven Americans would be poor without the safety net. That translates into more than 40 million people.[4]

Over the past three decades, policymakers changed the safety net substantially so that it now does much more to promote work and support low-income working families whose earnings aren’t high enough to make ends meet — and much less to support low-income families that lack earnings.

Thirty years ago, the main assistance programs for families with children were the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, Medicaid, food stamps, and a very small EITC. AFDC provided assistance largely to single mothers during periods of joblessness; if a mother earned too much to qualify, she would lose not only income assistance but also Medicaid. Medicaid generally covered only parents and their children as well as elderly and disabled people who received cash welfare benefits; the working poor did not qualify. Far fewer households with children that received food stamps were working. The EITC did little more than offset some of the payroll taxes that working poor families owed. Child care assistance mainly supported families receiving AFDC who were in education or training programs; it did little to assist the working poor.

The situation is very different today.

Refundable Tax Credits

Tax credits do much more today to “make work pay” than 30 years ago. In 1983, the EITC was not large enough to offset the payroll taxes of a family of four with a full-time, minimum wage worker, leaving this family well below the poverty line. Today, the EITC and CTC lift such a family much closer to the poverty line, even after accounting for the payroll taxes they pay.

- In 1983, a full-time, minimum wage worker earned about $6,700 per year and was eligible for a maximum EITC of $500, about equal to the employee’s share of payroll taxes.[5] The worker’s earnings equaled about 66 percent of the poverty line for a family of four[6] and, once the worker’s payroll taxes and EITC were figured in, the worker’s income was virtually unchanged at 67 percent.[7]

- Today, a full-time, minimum wage worker earns only 61 percent of the poverty line for a family of four. But, after accounting for the family’s earnings, payroll taxes, and both the EITC and CTC, the family’s income rises to 87 percent of the poverty line, a significant improvement in that family’s economic well-being.

For families that have very low earnings and are just gaining a toehold in the labor market, the size of their EITC and CTC increases as the families’ earnings rise, countering the phase-down of some other benefits that fall as earnings rise. These tax credits boost the families’ overall income and strengthen incentives to work.

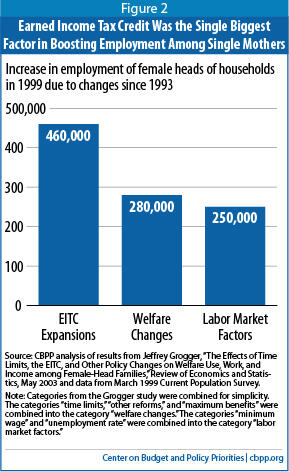

The EITC promotes work, as numerous studies have found. “The overwhelming finding of the empirical literature is that the EITC has been especially successful at encouraging the employment of single parents, especially mothers,” write economists Nada Eissa of Georgetown University and Hilary Hoynes of the University of California at Davis.[8] While policymakers often point to the 1996 welfare law’s creation of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) as the main reason for increased work among single mothers, the research indicates that the EITC expansion of the 1990s had an even larger effect in producing those gains.[9] (The EITC expansions and the changes in welfare reinforced each other in inducing more single mothers to work.)

Research also shows that, by boosting employment among single mothers, the EITC has produced large declines in the receipt of cash welfare assistance:

- The EITC expansions of the 1990s moved more than half a million families from cash welfare assistance to work, according to research by economists Stacy Dickert of Michigan State University, Scott Houser of the Colorado School of Mines, and John Karl Scholz of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.[10]

- The EITC likely contributed about as much to the decline in the receipt of cash welfare assistance among female-headed families in the 1990s as did time limits and other welfare reforms, according to the University of Chicago economist Jeffrey Grogger’s study of the effects of welfare time limits, the EITC, and other policy changes implemented from 1993 to 1999.[11]

Finally, as discussed below, research shows that income supports like the EITC have a positive impact on children’s educational outcomes and later employment success, indicating that the EITC promotes work for multiple generations.

Medicaid

Before the Medicaid expansion of the early 1980s, children and parents who received AFDC qualified for Medicaid but children in working-poor families did not. Today, virtually all low-income children are eligible for Medicaid or CHIP, and only a small fraction of the children receiving coverage through these programs also receive cash welfare assistance. Most children covered by Medicaid or CHIP are in low-income working families.

Among parents, the story is different. Although substantial numbers of working-poor parents are eligible for Medicaid, many are not because most states have set eligibility limits for parents far below the poverty line. Working-poor parents lose eligibility for Medicaid in the typical state when their earnings reach just 61 percent of the poverty line.

Public programs bear administrative costs to assure program integrity (i.e., that the people served are truly eligible and that the programs provide the appropriate level of benefits and services to eligible recipients). But the administrative costs in the major means-tested programs are modest.

A recent examination of six major means-tested programs — Medicaid, SNAP, Supplemental Security Income, Section 8 housing vouchers, school meals programs, and the EITC — found that in each of them, 90 to 99 percent of spending goes for benefits or services that reach beneficiaries. Thus, federal and state administrative costs combined account for only 1 to 10 percent of program costs, with most of those costs coming at the state level.

This situation will change under health reform. Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), states can expand Medicaid to cover all poor and near-poor non-elderly adults under favorable financing terms. In addition, uninsured children and adults with incomes between 100 percent and 400 percent of the poverty line will be able to receive subsidized coverage through the new health insurance exchanges. For states that adopt the ACA’s Medicaid expansion, health reform will complete the transition from a Medicaid structure that linked eligibility for subsidized health insurance to receipt of welfare benefits — leaving many low-income working individuals and families uninsured — to one that provides access to affordable coverage for virtually all low-income children and adults, including nearly all of the working poor.

SNAP

In February 1983, only 23 percent of households with children receiving food stamps were working.[12] Today, this share has more than doubled; about half of SNAP households with children work. Moreover, among households with children that include an adult who isn’t elderly or disabled, 87 percent of the households receiving SNAP in a given month include an individual who worked in the prior year or will work in the following year.[13]

The number of SNAP households that have earnings while participating in SNAP has been rising for more than a decade. It has more than tripled over this period, from about 2 million in 2000 to about 6.4 million in 2011. The growth is due in part to an increase in the percentage of eligible working households that participate in SNAP, as the result of bipartisan efforts at the federal, state, and local levels to make the program more accessible to working families. In addition, during the recent recession and ensuing slow recovery, the number of working households whose earnings are too low to keep them out of poverty has risen.

Under the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations, the Agriculture Department took steps to improve access to SNAP for eligible low-income working families and families moving from welfare to work, such as reducing unnecessary paperwork requirements and ensuring that leaving welfare for work did not cause a family to lose SNAP benefits. Eric M. Bost, who served as Bush’s Undersecretary of Agriculture for Food, Nutrition, and Consumer Services, described the program’s role in supporting work and advancing welfare reform goals at a June 2001 congressional hearing:

The Food Stamp Program has also contributed to the success of welfare reform by supporting the transition from welfare to work. The reasons are easy to understand — if you are worried about your family’s next meal, it is hard to focus on your future. For many households, food stamps can mean the difference between living in poverty and moving beyond it. And for many, it has.[14]

Child Care Assistance

The federal government provides funds to states for child care assistance programs. States use them — along with their own funds — to help some low-income working parents and parents in education and training programs pay for child care.

Before 1990, nearly all federal child care assistance went to families who were receiving case welfare assistance through AFDC and had a parent participating in AFDC-related education or training programs, and only a small amount of it went to families leaving welfare for work. In 1990, President George H.W. Bush and Congress established the Child Care and Development Block Grant and the At-Risk Child Care program, and funding for child care assistance for low-income working families has risen modestly since then. Still, due to insufficient funding, only about one in six low-income children eligible for child care assistance under federal rules receives it.[15]

Safe, reliable child care is expensive. Full-time, center-based care for a 4-year-old child costs an average of almost $7,600 in the median state in 2012, according to Child Care Aware, an organization of child care resource and referral agencies across the country. Full-time care for an infant costs about $9,400 in the median state.[16] These costs far exceed what a mother working full-time at the minimum wage typically can afford on her own.

For low-income parents, access to reliable child care is important for long-term job retention. Families that, due to cost concerns, use informal child care arrangements (e.g., where family members serve as child care providers) or string together multiple care arrangements will more likely experience child care-related work disruptions, recent research shows. Low-wage workers who miss work or arrive late because of child care mishaps are more likely to be fired from their jobs. Child care subsidies can provide consistent access to stable child care so that parents can work dependably.[17]

As research increasingly finds, certain investments in assistance, health care, and education for children in low-income families can have positive long-term effects, such as improving children’s health status, educational success, and future work outcomes. These positive effects, in turn, can benefit the country by improving the skills of our workforce so that we are more fully using the talents of our people.

Research shows that:

Programs that supplement the earnings of low-income working families, like the EITC and CTC, boost children’s school achievement and future economic success, and participating children are healthier as infants and have more economic success as adults. Harvard University economists Raj Chetty and John N. Friedman and Columbia University economist Jonah Rockoff analyzed school data for grades 3-8 from a large urban school district, as well as the corresponding US tax records for families in the district. They found that even under conservative assumptions, additional income from the EITC and CTC leads to significant increases in students’ test scores.[18] After studying nearly two decades’ worth of data on mothers and their children, University of California at San Diego economist Gordon B. Dahl and University of Western Ontario economist Lance Lochner concluded that additional income from the EITC significantly raises the combined math and reading test scores of students.[19]

This research on the EITC and CTC is consistent with research on other income supplements for working families. After reviewing the research, Northwestern University’s Greg J. Duncan and the University of Wisconsin’s Katherine Magnuson found “convincing evidence” of improved educational outcomes from studies of the EITC and other programs that supplement low-income families’ earnings.[20] Providing an income supplement of about $3,000 (in 2005 dollars) to a working parent during a child’s early years, they concluded, may boost that child’s achievement by the equivalent of about two extra months of schooling.[21]

The EITC and CTC’s beneficial effects appear to follow children into adulthood. Harvard’s Chetty and his coauthors note evidence that test score gains can lead to significant improvements in students’ later earnings and employment rates when they become adults.[22] Their finding parallels other research that followed low-income children from early childhood into their adult years and found a lasting beneficial effect when the children’s families received additional income (regardless of the income source). The researchers found that each additional $3,000 in annual income in early childhood is associated with an added 135 hours of annual work as a young adult and an additional 17 percent in annual earnings.[23]

Finally, University of California at Davis researchers Hilary W. Hoynes, Douglas L. Miller, and David Simon examined the effect of EITC expansions that policymakers enacted in the 1990s, by comparing changes in birth outcomes for families eligible for the largest increases in their EITC to changes in outcomes for families eligible for little or no increase. They found that infants born to mothers who were eligible for the largest EITC increases experienced the greatest improvements on a number of birth indicators associated with more favorable long-term outcomes for children, such as a reduced incidence of low birth weight and premature births. [24]

Head Start children fare better years later. Researching the long-term impacts of Head Start, Harvard’s David Deming found that children who participated in the program between 1984 and 1990 later were more likely to complete high school, less likely to be out of school and out of work, and less likely to be in poor health. Head Start, he concluded, “closes one-third of the gap” on a combined measure of adult outcomes "between children with median and bottom-quartile family income.” Some questions remain about whether the advantage that Head Start children enjoy when they enter kindergarten endures in later school years, and there is broad agreement that policymakers should pursue further reforms to strengthen the program’s impacts in these areas. But Deming tracked children for a longer period, beyond just their school years, and he found that the program’s positive influence is evident in later years in various important areas of children’s lives such as high school completion, college enrollment, health status, and being either employed or in school. [25]

Similarly, the University of Chicago’s Jens Ludwig and the University of California at Davis’ Douglas Miller find evidence that Head Start has a positive effect on children’s health — specifically, that mortality rates among children aged 5 to 9 fell due to screenings conducted as part of Head Start’s health services.[26]

Pell Grants help low-income students overcome significant barriers to earning a college education. Pell Grants provide assistance to more than 9 million low- and moderate-income students to pay for college. Students qualify for the grants based on their income, assets, and family size; three-quarters of recipients had family incomes below $30,000 in the 2010-2011 academic year.[27] Need-based grant aid improves college access, studies show, especially among minority students.[28]

Pell Grants, in particular, appear to promote college completion.[29] A 2009 Education Department study found that, after controlling for barriers to college success such as financial independence, college graduates who received these grants earned their degrees faster than non-recipients.[30] And a 2008 study found that low-income students who receive a Pell Grant were 63 percent less likely to drop out than low-income students without such a grant.[31] College graduates have higher employment rates and earnings and lower poverty rates than those who lack a college degree.[32] By helping students graduate, Pell Grants improve students’ chances of success in the labor market.

Housing assistance programs reduce risk factors for poor school outcomes. Four housing-related problems — homelessness, frequent moves that result in school changes, overcrowding, and poor housing quality — can impair children’s academic achievement, research shows. Children in homeless families are more likely than other low-income children to drop out of school, repeat a grade, or perform poorly on tests.[33] Frequent moves, particularly those that cause children to change schools during kindergarten or high school, tend to worsen educational performance (both for the children andfor their classmates in schools in which large numbers of students move in or out during the year).[34]

Research shows, moving often imposes stress on students, which can cause students to have difficulty concentrating.[35] Moreover, when students change schools, they can suffer gaps in their learning because they miss school days and because different schools cover material in a different order. In addition, changing schools can impair the development of the bond with teachers that disadvantaged children often need to perform well.[36] Children also may miss school due to homelessness or frequent moves or because they live in housing that may exacerbate a child’s asthma or result in lead poisoning.[37] And, children living in overcrowded housing may lack the space or quiet to do their homework, and they may also suffer from stress-related behavior problems that interfere with academic performance.[38]

Housing assistance reduces these housing-related problems. In a multi-site, rigorous evaluation, low-income families that received housing vouchers were 74 percent less likely to become homeless, 48 percent less likely to live in overcrowded housing, and moved fewer times over a five-year period than similar low-income families that didn’t receive housing assistance.[39] By lowering families’ housing costs to 30 percent of their income and requiring that housing meet minimum quality standards, federal housing assistance eliminates or substantially reduces several of the primary causes of homelessness and involuntary moves.[40] Federal rules also bar overcrowding in the units that families rent with the help of vouchers.

Dr. Jack Shonkoff, who directs Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child, and other researchers have shown that when children live in very stressful situations — in dangerous neighborhoods, in families that have real difficulty putting food on the table, or with parents who cannot cope with their daily lives — they may experience what he calls “toxic stress.” This stress creates damaging neurological impacts that negatively affect the way a child’s brain works and that impede children’s ability to succeed in school and develop the social and emotional skills to function well as adults.

For example, one study documented that a young adult’s working memory (measured at age 17) “deteriorated in direct relation to the number of years the children lived in poverty (from birth through age 13).” The study found that “such deterioration occurred only among poverty-stricken children with chronically elevated physiological stress (as measured between ages 9 and 13).” That is, the mechanism by which early childhood poverty affected memory appears to be related to the stress that “usually accompanies poverty.”a

Recent research published by the National Bureau of Economic Research also has found connections between swings in income around the time of a pregnancy and dangerous levels of stress that affects both the mother and baby. Temporary spells of low income during pregnancy appear to come with an increase in the maternal stress hormone cortisol; a high cortisol level during pregnancy was associated with negative child outcomes — specifically, “a year less schooling, a verbal IQ score that is five points lower and a 48 percent increase in the number of chronic [health] conditions” for the exposed children, compared to their own siblings who were born at times when the family had lower stress (and, usually, higher income).b

Programs that help poor families with children afford the basics may help improve longer-term outcomes for children by reducing the added stress that parents or children may experience if they cannot pay their bills or don’t know how they will put food on the table. While researchers are only starting to explore the relationship between safety-net programs and toxic stress and its long-term consequences, early findings are striking.

University of California at Davis economist Hilary Hoynes and her colleagues find that “access to food stamps in utero and in early childhood leads to significant reductions in metabolic syndrome conditions (obesity, high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes) in adulthood and, for women, increases in economic self-sufficiency (increases in educational attainment, earnings, and income, and decreases in welfare participation).”c Other researchers also found signs of reduced stress (such as less inflammation and lower diastolic blood pressure) among mothers targeted by the 1993 expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit; this expansion was also followed by a significant improvements in self-reported health status for the affected mothers.d

a Gary W. Evans, Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, and Pamela K. Klebanov, “Stressing Out the Poor: Chronic Physiological Stress and the Income-Achievement Gap,” Pathways, winter 2011, http://www.stanford.edu/group/scspi/_media/pdf/pathways/winter_2011/PathwaysWinter11.pdf

b Anna Aizer, Laura Stroud, Stephen Buka (2012), “Maternal Stress and Child Outcomes: Evidence from Siblings,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 18422, www.nber.org/papers/w18422.pdf.

c Hilary W. Hoynes, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Douglas Almond (2012), “Long Run Impacts of Childhood Access to the Safety Net,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 18535, www.nber.org/papers/w18535.

d William N. Evans and Craig L. Garthwaite (2010), “Giving Mom a Break: The Impact of Higher EITC Payments on Maternal Health,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 16296, www.nber.org/papers/w16296.

SNAP improves long-term health and self-sufficiency. While reducing hunger and food insecurity and lifting millions out of poverty in the short run, SNAP brings important long-run benefits. A new NBER study examined what happened when government introduced food stamps in the 1960s and early 1970s and concluded that children who had access to food stamps in early childhood and whose mothers had access during their pregnancy had better health outcomes as adults years later, compared to children born at the same time in counties that had not yet implemented the program. Along with lower rates of “metabolic syndrome” (obesity, high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetes), adults who had access to food stamps as young children reported better health, and women who had access to food stamps as young children reported improved economic self-sufficiency (as measured by employment, income, poverty status, high school graduation, and program participation).[41]

Medicaid has important health benefits for both children and adults. Children covered by Medicaid or CHIP are more likely than uninsured children to receive important preventive services, such as well-child check-ups, that are important for spotting health problems early.[42] For adults, Medicaid participation is associated with better health, lower mortality, and less household debt. Adults in Oregon who received Medicaid through a random “lottery” system were 40 percent less likely than uninsured adults to suffer a decline in their health over a six-month period, according to what’s widely regarded as the most important and rigorous study on Medicaid’s effects on beneficiaries.[43] The study also found that people with Medicaid were 40 percent less likely than those without insurance to go into medical debt or leave other bills unpaid in order to cover medical expenses. In addition, research published in the New England Journal of Medicine reported that expansions of Medicaid coverage for low-income adults in Arizona, Maine, and New York reduced mortality by 6.1 percent.[44]

Safety net programs provide important assistance to struggling families, help ensure that low-income individuals have access to affordable health care, and provide increased educational opportunities to low-income students. These efforts reduce poverty and hardship and promote work in the short run, and they also have important positive effects on educational, health, and employment outcomes in the long run.

As policymakers embark on the necessary work of further reducing long-term budget deficits, their approach could have important consequences for tens of millions of low- and moderate-income Americans. If policymakers take an even-handed approach, one that combines spending cuts with an adequate mix of new revenues, they can reduce deficits without increasing poverty and the ranks of the uninsured or weakening efforts to ensure that children have more opportunity to succeed in the classroom and later in the labor market. If, however, policymakers cut deeply into programs that assist low-income individuals and families, we will likely see more poverty and hardship as well as fewer paths to opportunity.