Chairwoman DeLauro, Ranking Member Cole, and members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify before you today. My name is Aviva Aron-Dine. I am the Vice President for Health Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a non-profit, non-partisan policy institute located here in Washington. The Center conducts research and analysis on a range of federal and state policy issues affecting low- and moderate-income families. Previously, I served in government in a number of roles, including as the chief economist at the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB), as Acting Deputy Director of OMB, and as a Senior Counselor at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), where my portfolio included Affordable Care Act (ACA) implementation and Medicaid, Medicare, and delivery system reform policy.

From the start of his presidency, President Trump has been clear that his goal is to repeal the ACA. While Congress considered and rejected a series of repeal plans in 2017, the Administration, and HHS in particular, has continued to pursue the overarching policy goals of those bills through administrative actions. In my testimony, I provide an overview of the progress made in expanding coverage and access to care under the ACA and recent HHS policies that have undermined the law. I then discuss why the ACA has so far proved relatively resilient in the face of these attacks, and why they may pose even greater risks going forward.

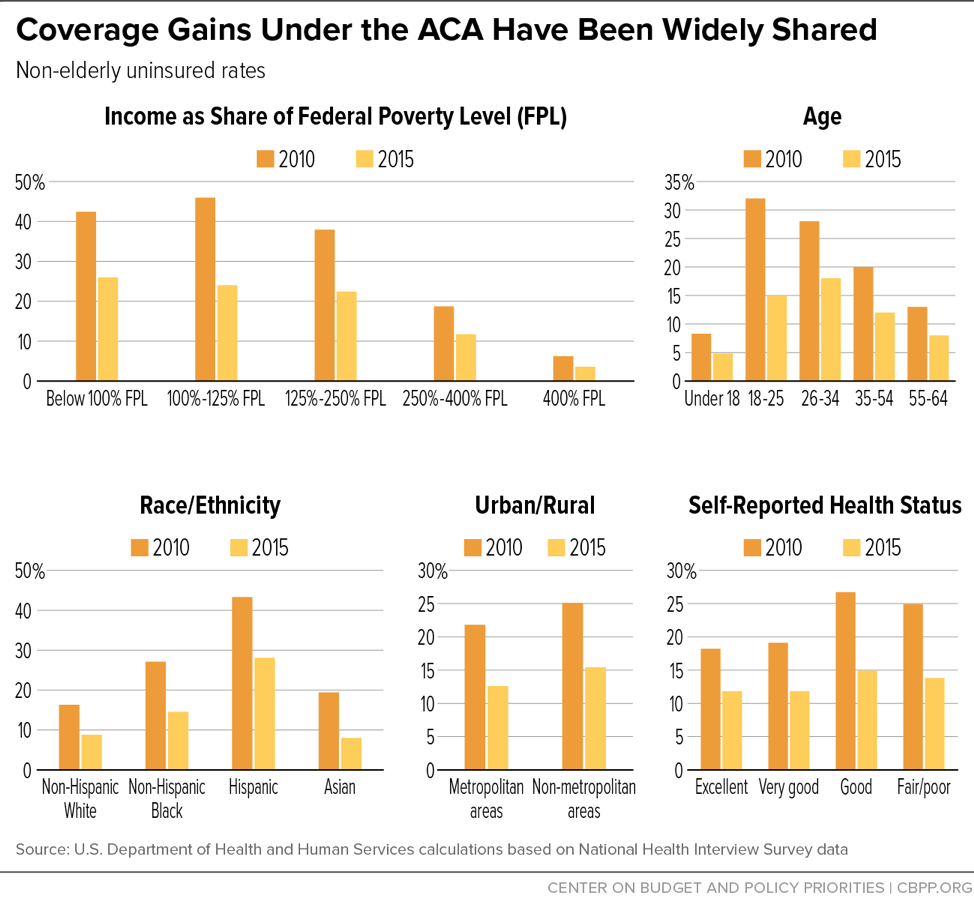

The most recent National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data show that the uninsured rate in the first half of 2018 remained stable at its lowest level in history: 8.8 percent, compared to 16.0 percent when the ACA was enacted in 2010.[1] NHIS data also show that these dramatic coverage gains have been broadly shared across non-elderly Americans (seniors already had near-universal coverage through Medicare). As shown in Figure 1, as the ACA’s major provisions took effect between 2010 and 2015, uninsured rates fell by 35 percent or more for low-, moderate-, and middle-income Americans; for all age groups and racial and ethnic groups; across both urban and rural areas; and for people in both good and poor health.[2] These gains reflect the combined effects of the ACA’s coverage provisions, including the expansion of Medicaid to low-income adults, the creation of the health insurance marketplaces and subsidies for individual market coverage, allowing young adults to remain on their parents’ plans until age 26, individual market reforms such as prohibiting insurers from denying coverage or charging higher premiums based on health status, and the individual mandate requiring most people to have health insurance or pay a penalty (although the individual mandate penalty was repealed effective this year).

The quality of health insurance has also improved, including for people already covered through their jobs. For example, as of 2009, 59 percent of people with employer coverage had plans with lifetime limits on benefits, while almost 20 percent had plans with no limit on out-of-pocket costs, exposing them to catastrophic costs in the event of serious illness.[3] The ACA prohibits lifetime (and annual) limits on coverage and requires plans to cap consumers’ annual out-of-pocket costs.

In the individual market, quality improvements have been even greater. As of 2013, before the ACA’s major individual market reforms took effect, 75 percent of individual market health plans excluded maternity care, 45 percent excluded substance use treatment, 38 percent excluded mental health services, and up to 17 percent excluded various categories of prescription drugs.[4] Today, all plans subject to ACA rules — the large majority of individual market policies (although the Administration is expanding the exceptions, as discussed below) — are required to cover these essential health benefits. The ACA also ended pre-existing conditions exclusions, which meant that even when people with pre-existing health conditions were able to obtain individual market coverage, that coverage often excluded treatment related to their pre-existing condition. And individual market insurance now offers greater financial protection. Among families with individual market coverage, average out-of-pocket costs (counting premiums, deductibles, co-pays, and co-insurance) fell by 25 percent in 2014, when the ACA’s major individual market reforms and marketplace subsidies took effect.[5]

There is growing evidence that the expansion of and improvements in coverage under the ACA are translating into improved access to care, financial security, and health. Nationwide, from 2010 to 2016, the share of non-elderly adults with problems paying medical bills fell 21 percent, and the share who didn’t fill a prescription or skipped treatment due to cost fell nearly 30 percent.[6]

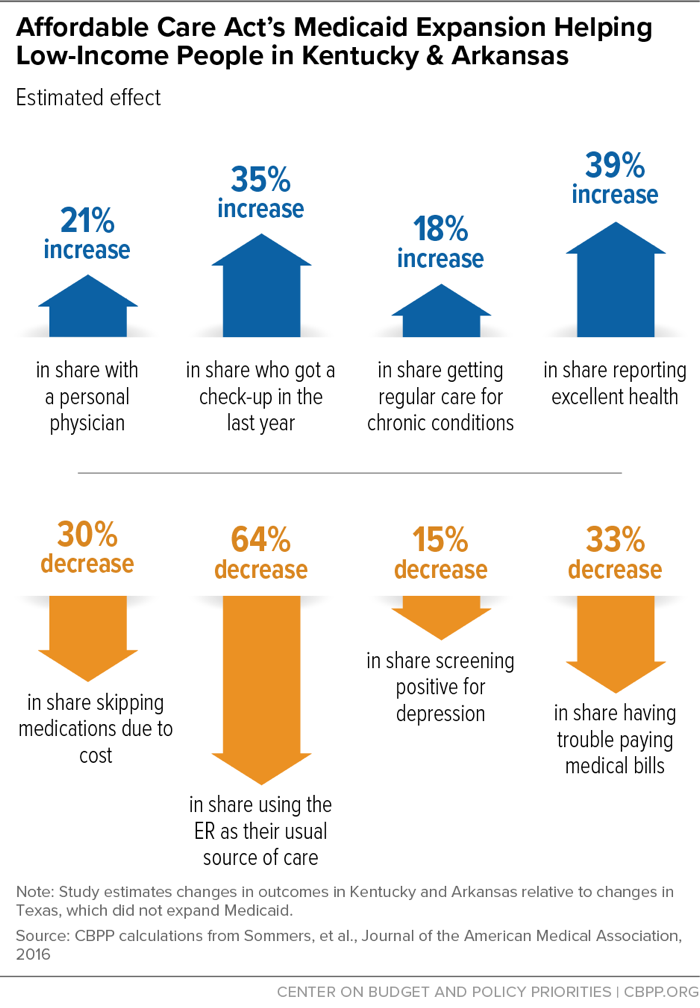

Some of the most in-depth research on the effects of the ACA has focused on those gaining coverage through Medicaid expansion. As shown in Figure 2, research on expansion’s effects in Kentucky and Arkansas has found sizable increases in the share of people with a personal physician, getting check-ups, getting regular care for chronic conditions, and reporting excellent health, as well as decreases in the share relying on the emergency room for care, skipping medications due to cost, struggling to pay medical bills, and screening positive for depression.[7]

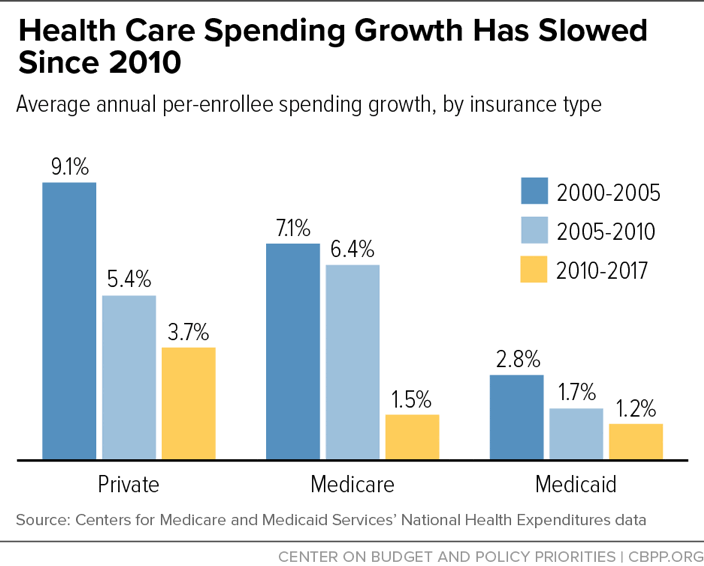

These expansions in coverage and access to care have coincided with a marked slowdown in per-enrollee health care cost growth — a slowdown to which the ACA has contributed, although it is certainly not the sole cause. As shown in Figure 3, per-enrollee spending growth since 2010 has been slower than over the previous decade in private insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid. This unexpected slowdown is yielding substantial savings for the federal government as well as for consumers. For example, annual growth in family premiums for employer-sponsored coverage has averaged 4.5 percent since 2010, compared to 7.9 percent over the previous decade.[8]

While the ACA is sometimes criticized for having focused on coverage expansions to the exclusion of cost, it contributed in important ways to this slowdown in health care cost growth. Most directly, the ACA instituted reforms to Medicare payment rates to more closely align them with costs; these reforms likely also had “spillover” impacts on health care cost growth for private payers.[9] The ACA also established incentives for hospitals to avoid unnecessary readmissions and prevent hospital-acquired conditions (such as infections); these programs have contributed to large declines in these adverse outcomes, improving care and reducing costs.[10]

Harder to quantify, but likely more important over the long run, the ACA created mechanisms for ongoing payment reform and experimentation in Medicare. Between the Medicare Shared Savings Program (the statutory accountable care organization program created as part of the ACA) and payment models developed through the ACA’s Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, more than 30 percent of Medicare payments are now tied to “alternative payment models” that reward efficient delivery of high-quality care, rather than being made on a purely fee-for-service basis.[11] Medicare’s leadership has also helped catalyze similar efforts by private insurers and employers and state Medicaid programs, a number of which are engaged in large-scale shifts toward population- or episode-based payment.

Of course, health care costs remain a challenge for families, the federal budget, and states, with additional reforms needed to deliver better care at lower cost. But the ACA put in place a foundation for payment reforms that are beginning to achieve results.

From the start of his presidency, President Trump has been clear that his goal is to repeal the ACA. The Administration supported the various ACA repeal bills debated and ultimately rejected by Congress, and it has continued to propose a version of repeal in its budget. All of these repeal proposals have key elements in common, including: effectively ending the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid to low-income adults and capping and cutting federal funding for other beneficiaries; ending or weakening protections for people with pre-existing conditions; cutting or eliminating financial assistance for ACA marketplace consumers; and taking other steps to reduce the federal role in promoting access to coverage. And all would cause millions of people to lose health insurance, while making coverage worse or less affordable for millions more.

With legislative repeal of the ACA off the table for now, the Administration has sought to achieve a version of repeal through the courts, declining to defend the ACA against litigation from state attorneys general in the Texas v. Azar lawsuit and instead asking the courts to invalidate the ACA’s major protections for people with pre-existing conditions. Especially relevant to this committee’s oversight role, the Administration has also continued to pursue some of the major policy objectives of the repeal bills through a range of administrative actions by HHS (as well as the Departments of Labor and Treasury). Table 1 summarizes these actions, a few of which I particularly want to bring to your attention.

-

A proposed rule that will cut premium tax credits and raise premiums or out-of-pocket costs for millions of people (January 2019). [12]A seemingly minor change included in the Administration’s recently released proposed rule setting ACA marketplace standards for 2020 would raise premiums for at least 7.3 million marketplace consumers by cutting their premium tax credits. The higher premiums — for example, $196 more for a family of four with income of $80,000 — would cause 100,000 people to drop marketplace coverage each year, according to the Administration’s estimates. The same proposal would also raise the ACA’s limits on total out-of-pocket costs (deductibles, co-payments, and co-insurance); such limits apply to employer as well as individual market plans and disproportionately protect people with pre-existing conditions, who are more likely to have health care costs high enough to reach the out-of-pocket limit. Both changes are the result of the Administration’s proposal to change how premium growth would be measured for purposes of certain ACA formulas, a change the rule acknowledges is discretionary, not required by any statute.

The proposed 2020 marketplace rule also reduces the federal marketplace user fee, potentially shortchanging basic marketplace operations, and it encourages navigators (federally funded in-person enrollment assistance programs) to enroll people through private web brokers (which often market plans not subject to ACA consumer protections) instead of through HealthCare.gov. It also suggests that the Administration is considering two even more harmful changes for future years: ending or limiting automatic re-enrollment, which lets returning marketplace consumers who don’t actively select a new plan maintain coverage for the next year, and attempting to end “silver loading,” a practice described below that lowers premiums, out-of-pocket costs, or both for millions of people.

-

Guidance encouraging states to pursue 1332 waivers that incorporate major elements of the congressional ACA repeal bills (October/November 2018).[13] The waivers allowed under section 1332 of the ACA are intended to let states experiment with alternative ways of providing coverage, subject to statutory “guardrails” that require the alternatives to cover as many people — with coverage as affordable and comprehensive — and at no higher cost to the federal government. Last October, HHS and Treasury issued guidance reinterpreting these guardrails to permit waivers that would result in people having coverage much less comprehensive than under the ACA or in large coverage losses among vulnerable groups. HHS then issued a discussion paper describing the types of waiver proposals it would like to see: proposals incorporating major elements of the 2017 ACA repeal bills. For example, the discussion paper invites proposals to replace the ACA’s tax credits, which adjust based on income and the cost of available coverage, with flat tax credits that would result in higher premiums for lower-income and older people. It also invites proposals to allow tax credits to be used to purchase plans that are exempt from the ACA’s protections for people with pre-existing conditions, an approach that could cause a death spiral in the portion of the health insurance market subject to these protections.

There is considerable doubt as to whether the ideas outlined in the HHS discussion paper meet even the modified guardrails from the October guidance, much less whether the proposed guardrails comply with the requirements of the statute. Nonetheless, if any states take up the Administration’s invitation to submit such waivers, it would put coverage and access to care for many thousands of people at risk. Also noteworthy, the HHS/Treasury guidance makes clear that the Administration is not interested in state proposals to expand public coverage, even if those proposals meet the section 1332 guardrails and notwithstanding the departments’ stated commitment to providing states with more flexibility.

-

Rules making health plans exempt from the ACA’s pre-existing conditions protections widely available (July/August 2018). Jointly with the Departments of Labor and Treasury, HHS issued a rule that allows a parallel health insurance market to operate selling plans that are not subject to the ACA’s consumer protections — plans allowed to deny coverage or charge higher premiums based on health status, impose annual and lifetime limits on coverage, and exclude essential health benefits. Where these “short-term, limited duration” plans were previously limited to three months, the new rule allows them to last up to one year and be renewed. People who enroll in these plans may face benefit gaps and be exposed to high costs if they get sick and need care, and troubling new research shows that short-term plans are frequently marketed to consumers without adequate information about their limitations.[14] Meanwhile, because the plans can offer lower premiums to healthy people (because they can vary premiums based on health status and offer reduced benefits), they will likely pull healthier enrollees out of the ACA individual market. (A separate rule issued by the Department of Labor expands the availability of association health plans, with similar consequences primarily for the small group market.)

Some states have acted to block the expansion of short-term plans, or already banned or limited them before the new rule. But in states where these plans are allowed to proliferate, middle-income individual market consumers who need comprehensive coverage — including those with pre-existing conditions — will pay higher premiums as a result. Lower-income consumers will be protected from these higher premiums, because premium tax credits will increase to compensate, but the result will be higher federal costs.[15] While the Administration has argued that the expansion of short-term plans is needed to provide more affordable options for people with incomes too high to qualify for subsidies, the additional federal dollars being used to protect subsidized consumers from the adverse effects of the rule could instead be used to help middle-income people (both those who are healthy and those who are not) afford comprehensive coverage.

-

Medicaid waivers that could cause hundreds of thousands of low-income adults to lose coverage (beginning January 2018). After Congress rejected legislation rolling back the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid to low-income adults, HHS began approving Medicaid waivers that, if implemented, will take coverage away from hundreds of thousands of expansion enrollees. The first of these waivers — Kentucky’s proposal to take coverage away from people who don’t meet monthly work requirements, pay premiums, or submit certain paperwork on time — was halted by a federal judge, who found that HHS had not shown how a waiver taking Medicaid coverage away from nearly 100,000 people could be consistent with the objectives of the Medicaid program. The first waiver actually implemented, Arkansas’ work requirement proposal, has already led more than 18,000 people — more than 1 in 5 of those subject to the new policy — to lose coverage.[16]

The coverage losses in Arkansas exceed estimates of how many beneficiaries subject to the new rules are neither working nor exempt. That strongly suggests working people and people whose disabilities or health problems should qualify them for exemptions are losing coverage, presumably due to problems completing new reporting and paperwork requirements. The data from Arkansas led the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC), Congress’s independent, non-partisan advisory panel on Medicaid policy, to urge HHS to halt Arkansas’ waiver and pause in approving similar policies in other states.[17] Instead, since MAPCAC issued its recommendation in November, HHS has approved four additional work requirement proposals (and re-approved Kentucky’s).

-

Outreach cuts that make it harder for consumers to learn about marketplace and Medicaid coverage (beginning January 2017). Immediately upon taking office, the Trump Administration stopped planned television advertising during the 2017 open enrollment period, which was still under way. The next fall, it cut the marketplace advertising budget by 90 percent. It also made large cuts to in-person consumer assistance (navigator) programs, which are especially important to vulnerable groups such as people with disabilities or other special needs, people with limited English proficiency, and people with limited access to or comfort using the Internet. Combined with additional cuts the following year, HHS has now cut the navigator program budget by more than 80 percent. It has also weakened the program in other ways, for example by eliminating requirements that navigators have a physical presence in the state they are paid to serve and that they be consumer-focused nonprofit organizations.[18] And, for the first time, navigators are encouraged to talk to consumers not just about marketplace options but about short-term and association health plans not subject to ACA rules.

Advertising and navigators are funded out of federal marketplace user fees. Funding for advertising and navigators could be restored either by directing HHS to spend the money out of user fees or by providing an appropriation for these purposes that would restore the amount the Administration has cut, close to $150 million. Legislation would also need to direct HHS how to use the funds, to make sure they are spent in a timely manner and to promote enrollment in comprehensive coverage.

It’s worth noting that the Administration has also taken actions undermining the ACA’s provider payment reforms. It withdrew a Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) demonstration testing bundled payments for certain cardiac procedures, shrank a demonstration testing bundled payments for joint and knee replacements, and urged Congress to rescind $800 million in CMMI funding. More recently, however, HHS’ statements and actions have suggested a more supportive posture toward payment reforms and CMMI demonstrations. Its policy in this area bears watching.

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| Major Outcomes of ACA Repeal Bills |

HHS Actions Advancing Similar Objectives |

|---|

| Ending the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid |

Encouraging and approving Medicaid waivers that include eligibility restrictions, such as work requirements, that will cause large drops in coverage among low-income adults |

| Ending or undermining various protections for people with pre-existing conditions |

Broadening availability of “short-term” and other plans exempt from key protections (joint with Labor/Treasury); offering states options to weaken essential health benefits and the risk adjustment program; proposing to raise limits on out-of-pocket costs (including for employer plans); encouraging states to adopt 1332 waivers further undermining protections |

| Sharply cutting marketplace financial assistance |

Proposing a change that will raise premiums, by cutting premium tax credits, for at least 7.3 million consumers; encouraging states to adopt 1332 waivers making large cuts to premium tax credits for lower-income people; considering trying to end “silver loading,” a practice that lowers premiums, out-of-pocket costs, or both for millions of marketplace consumers |

| Weakening or eliminating the federal role in promoting access to coverage |

Cut advertising by 90 percent and in-person consumer assistance by more than 80 percent; shortened open enrollment by half; created new obstacles to maintaining marketplace coverage and enrolling in coverage through special enrollment periods; considering ending or limiting automatic re-enrollment for returning marketplace consumers |

Given the Administration’s actions, as well as the repeal of the ACA individual mandate penalty as part of the 2017 tax bill and the uncertainty created by a year’s debate about repealing the ACA, many expected more deterioration in marketplace enrollment and overall uninsured rates than has so far occurred. HealthCare.gov enrollment is down 1.2 million since its peak in 2016, but when the final tally is in for 2019, it seems that close to 11.5 million people will be signed up for coverage nationwide (across HealthCare.gov and state marketplaces). And, as noted above, federal surveys show the uninsured rate remained at its post-ACA historic low through the first half of 2018.[19]

Of course, this doesn’t address the counterfactual: in a more favorable policy environment, uninsured rates might have continued to fall, particularly given the declining unemployment rate. But there are also several important forces that have helped sustain coverage gains so far, but that could be undermined by the Administration’s actions or other actions it has said it might take.

First, the ACA’s tax credit structure makes the marketplaces highly robust. Marketplace consumers with incomes below 400 percent of the poverty line (about $100,000 for a family of four, or $50,000 for a single adult) pay a fixed percentage of income to purchase the benchmark (second-lowest-cost silver) plan available to them where they live. Premium tax credits adjust as needed to make up the difference between that percentage of income and sticker price premiums. This means that most consumers — more than 60 percent of all people purchasing individual market policies that are subject to ACA rules — are shielded from premium increases, including those resulting from Administration policies.[20] The large majority of these subsidized consumers have plan options with premiums (after tax credits) of less than $100 per month, which means marketplace coverage should remain more attractive than short-term plans, even for those who are healthy.[21]

So far, the Administration’s actions have left premium tax credits largely unscathed. In fact, one of the Administration’s major efforts to undermine the marketplaces — its decision to stop reimbursing insurers for cost sharing reductions (CSRs) — ended up making premium tax credits more generous. President Trump was clear that his intent in stopping CSR payments was to destabilize the ACA marketplaces.[22] But, partly thanks to state regulators who acted quickly to protect their markets, it instead resulted in a mostly smooth transition to “silver loading,” or insurers building the cost of CSRs into marketplace silver plan premiums. That approach results in larger premium tax credits, lowering premiums, deductibles, or both for about 2 million moderate-income HealthCare.gov consumers in 2018 (likely more this year).[23] It also allows unsubsidized consumers to avoid the higher premiums from non-payment of CSRs by buying non-silver plans. Overall, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) now estimates that the President’s decision not to pay CSRs is increasing coverage by 500,000 to 1 million people per year.[24] In other words, the Administration’s likely unintended increase in premium tax credits has helped counterbalance its other actions undermining the ACA.

The crucial role premium tax credits have played in sustaining coverage to date is part of why it’s so concerning to see HHS apparently looking for administrative options to cut premium tax credits. As discussed above, the proposed rule setting 2020 marketplace standards includes a discretionary formula change the effect of which is to cut tax credits and raise premiums for subsidized consumers. In the same proposed rule, HHS noted that it had considered even larger cuts to premium tax credits, and it expressed interest in ending silver loading in future years, although it is not clear it can do so administratively. Meanwhile, HHS’s 1332 waiver discussion paper encourages states to develop waiver proposals that would upend the structure of premium tax credits altogether, by delinking them from income and the cost of coverage or allowing them to be used for plans not subject to ACA rules (although, as noted, such waivers likely could not comply with the statutory 1332 guardrails).

A second factor sustaining marketplace enrollment is that, by the start of the Administration, the marketplaces had a strong base of returning consumers. More than 80 percent of these consumers report that they are satisfied with their coverage, and they remain enrolled at high rates.[25] This has helped sustain overall marketplace enrollment. It’s therefore very troubling to see the Administration suggest (as discussed above) that it is considering ending or limiting automatic re-enrollment for returning consumers. While a high fraction of returning marketplace consumers do come back and actively select a plan, a sizable minority depend on having coverage automatically continue from year to year, much as many people with employer plans do.

Moreover, there is always churn in individual market enrollment: there should be, as people find and leave jobs with employer coverage or see their incomes fall below or rise above Medicaid income limits. Stable marketplace enrollment therefore requires enrolling millions of new consumers each year. But new consumers are the ones less likely to visit HealthCare.gov and check out options without advertising and without the incentive provided by the individual mandate penalty. Consistent with that, while HealthCare.gov returning consumer enrollment is actually up from last year, new consumer enrollment is down more than 15 percent. Over time, challenges attracting new consumers will compound into increasingly large drops in returning consumer and total enrollment.

A third important force sustaining overall coverage rates is that enrollment in Medicaid expansion has remained strong. And going forward, enrollment will increase further as new states expand. Despite the Administration’s efforts to discourage states from adopting expansion,[26] Maine and Virginia are newly implementing expansion this year; voters in Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah adopted ballot initiatives directing their states to expand; and additional states such as Kansas, North Carolina, and Wisconsin are seriously considering expansion. But the Medicaid eligibility restrictions newly allowed by HHS under this Administration threaten to offset these coverage gains. The coverage losses projected under Kentucky’s waiver alone, for example, are greater than the coverage gains projected to result from expansion in Maine or Nebraska.[27]

Given the large risks recent HHS actions pose to programs that cover millions of Americans, this committee’s oversight role is crucial. Thank you for holding this hearing, and I hope you will continue to closely examine the impact of HHS policy toward the marketplaces and the ACA Medicaid expansion. Almost nine years after passage of the ACA, and five years after the initial implementation of its major coverage reforms, there are many opportunities to learn from federal and state experience with the law, and to move forward to close remaining gaps in coverage and make coverage and care more affordable. But an important first step is to stop moving backward.