BEYOND THE NUMBERS

With Federal Rules Weakened, States Should Act to Protect Against Short-Term Health Plans

New federal rules, released today, allow short-term plans exempt from pre-existing condition protections and benefit standards to last for up to one year and to be renewed. It’s now up to states to protect their residents and their insurance markets from an expansion of substandard coverage. In several states, policymakers of both parties have already acted to set their own limits and consumer protections for short-term plans. Others are in the process of doing so, and all should consider taking action.

The federal changes, proposed earlier this year, roll back 2016 regulations defining short-term plans as those lasting less than three months, changing the definition to include those lasting less than a year.

This would let a parallel market for skimpy plans operate alongside the market for comprehensive individual health insurance, exposing consumers to new risks and raising premiums for those seeking comprehensive coverage, especially middle-income consumers with pre-existing conditions. Importantly, the rules take effect in early October, just before the November 1 start date for the Affordable Care Act (ACA) open enrollment period. This sets up a confusing situation for consumers, who will have a limited time to sign up for more comprehensive 2019 ACA plans but are likely to be subjected to heavy marketing from companies selling short-term plans as a long-term alternative.

Short-term plans do not have to cover all of the ACA’s essential health benefits, and they often don’t cover such essential benefits as maternity and mental health care, substance-use disorder treatment, and prescription drugs. Short-term plans can deny coverage or charge higher prices to people with pre-existing conditions, and they typically do not cover medical services related to a pre-existing condition.

Short-term plans are likely to offer healthier people lower premiums (because the plans include reduced benefits and cover less costly populations), and thus will lure healthy enrollees away from the individual and small-group markets and leaving a costlier group behind. This dynamic, known as adverse selection, would raise premiums for traditional, more comprehensive health coverage and undermine ACA protections for people with pre-existing conditions. Meanwhile, healthy people who enroll in these plans may find themselves facing gaps in coverage and exposed to catastrophic costs if they get sick and need care.

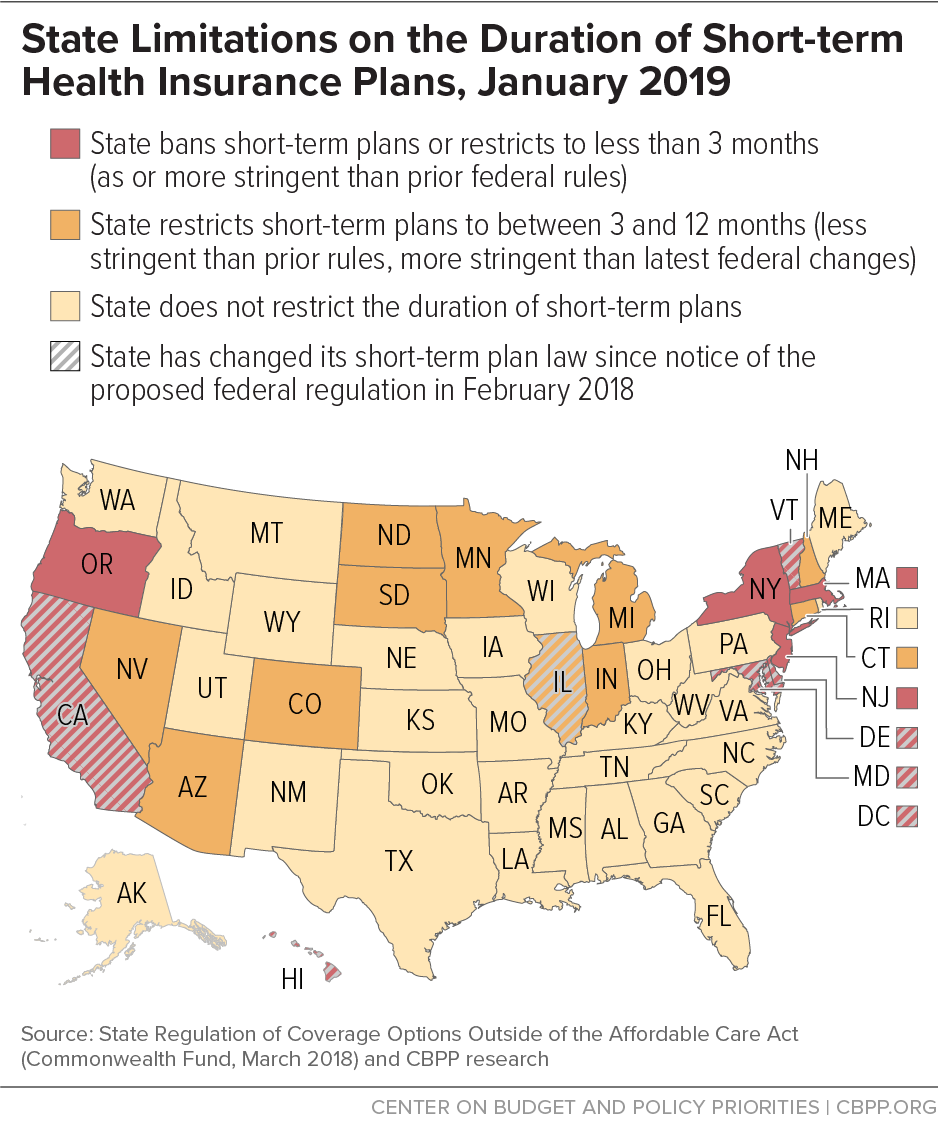

But even with today’s federal rule changes, states have the authority to set their own standards for short-term plans. To date, the following states have acted:

- In Maryland, a new law, passed on a bipartisan basis and signed by Republican Governor Larry Hogan, limits short-term plans to less than three months — even if the Administration finalizes its proposal to let short-term plans last up to a year. The law also clarifies that insurers can’t extend or renew short-term plans.

- A new Vermont law, signed by Republican Governor Phil Scott, limits short-term plans to three months or less, prohibits renewals and extensions, and directs the insurance commissioner to provide consumer disclosure language for the plans and establish minimum financial, marketing, and other standards.

- Hawaii’s legislature passed a bill, signed by Democratic Governor David Ige, that prohibits insurers from issuing a short-term plan to someone who was eligible to buy coverage through the ACA marketplace during an open or special enrollment period the prior year. The bill also says that any short-term plan that is sold must be limited to less than 91 days and can’t be renewed or extended.

- The Illinois General Assembly passed legislation on a bipartisan basis that would limit short-term plans to six months, restrict extensions and renewals, and require warning language for consumers. Republican Governor Bruce Rauner has not yet signed the law.

Other states are also making progress. Washington state’s insurance commissioner has initiated a rule-making process to clarify standards for short-term plans. California’s Senate passed legislation prohibiting the sale of short-term plans beginning January 2019; the state’s Assembly is considering it now.

Other states have warded off efforts to expand short-term plans, at least so far. In Virginia, Democratic Governor Ralph Northam vetoed a bill that, mirroring the federal rule change, would have allowed short-term plans to last up to 364 days. In Minnesota, a proposal to roll back the state’s existing protections failed to advance.

Before the recent flurry of activity, three states — Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York — already effectively prohibited short-term plans, and Oregon limits short-term plans to three months or less and restricts renewals. Several other states have protections in place that may at least mitigate the effects of the rule changes. (See map.) Yet most lack sufficient protections against adverse selection that could result from the federal rule changes for short-term plans (and also for Association Health Plans, or AHPs, as we explained here).

Even as the Trump Administration’s policies undercut the ACA, states retain broad authority to protect consumers and create a level playing field for insurers in their individual and small-group markets — and insurers, patient groups, and consumer advocates have urged them to exercise that authority. Other states should follow Maryland, Vermont, and Hawaii and implement protections against short-term plans.