BEYOND THE NUMBERS

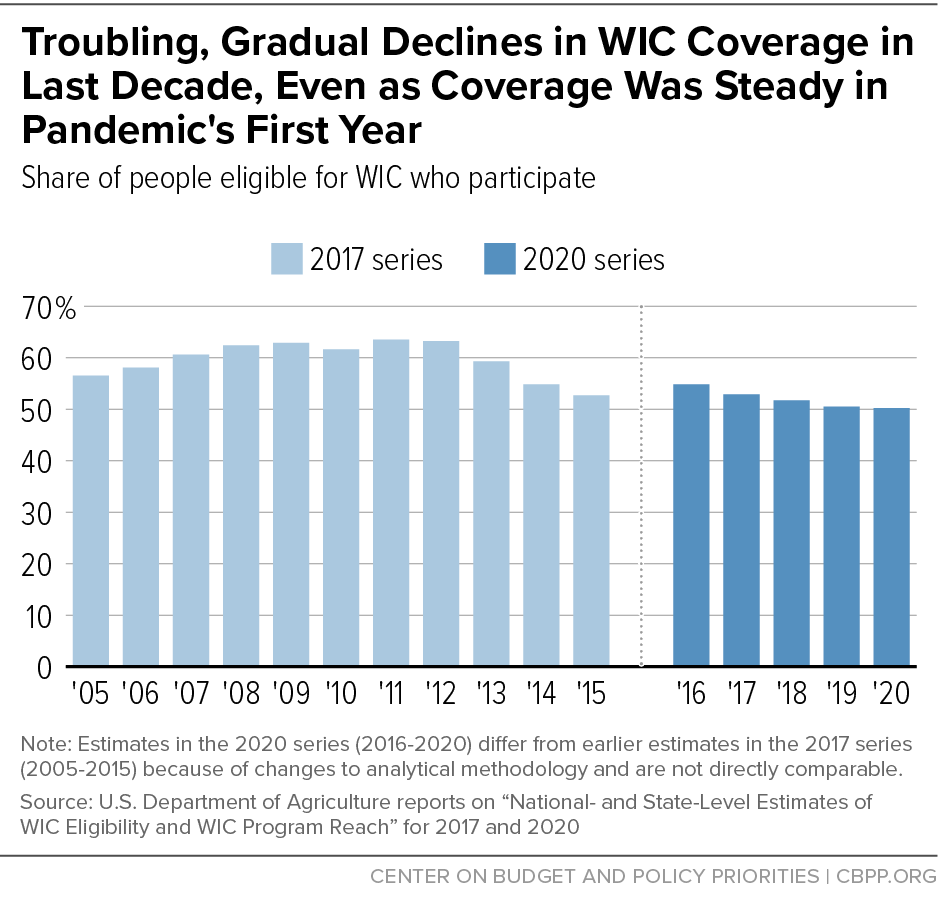

The share of eligible individuals participating in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) remained steady in 2020, a testament to the program’s resilience as the pandemic set in, parents lost work, and its operations had to transform overnight. And while longer-term participation trends show that an increasing share of low-income families with young children are missing out on this important nutrition resource, what might be misinterpreted as a drop in the WIC coverage rate in 2020 is actually due to a methodological change in the way the Agriculture Department (USDA) analyzed the data. Understanding that the coverage rate decline hasn’t been sudden or pandemic-related, but rather longer term, could help policymakers’ efforts to increase the coverage rate.

Participating in WIC is associated with improvements in health and developmental outcomes for low-income pregnant and postpartum people, infants, and children. The latest data show that only about half, or 50.2 percent, of eligible individuals participated. While that’s worrisome — and signals that far more low-income families could be benefiting from the food, nutrition counseling, breastfeeding support, and referrals to health care that WIC provides — that figure is statistically unchanged from 2019’s rate of 50.5 percent.

Coverage rates also differed widely across participant categories. In 2020 WIC reached twice the share of eligible infants (81.7 percent) than eligible children aged 1 to 4 (40.6 percent). Eligible postpartum people also participated at higher rates (68.5 percent) than eligible pregnant people (45.6 percent).

The stability in the coverage rate from 2019 to 2020 indicates that WIC responded well to the pandemic, under the circumstances. WIC administrators previously provided services almost exclusively in person but had to switch largely to remote, and health departments redeployed some staff to do frontline work related to the pandemic. These factors may have affected staff capacity to run the program and conduct outreach about the changes. In addition, families in some states had to visit WIC clinics in person to receive their benefits, which posed a burden and a health danger due to the pandemic and, like the other changes, risked reducing overall participation by eligible individuals.

But there’s no sign that reduction occurred. In addition to the WIC coverage rate remaining unchanged in the pandemic’s first year, USDA reported that overall food insecurity did not increase from 2019 to 2020. In combination with other food assistance for families with children, WIC may have helped low-income families supplement their food budgets and obtain enough groceries during that period.

Rather, WIC’s coverage rate declines have been gradual since 2016, when the rate was 54.8 percent. The latest data draw on an updated methodology — based on the first comprehensive review of USDA’s approach since 2003 — which the Department designed to improve the consistency of estimates over time. USDA released new estimates for 2016 to 2019 that are lower than estimates for those years based on the old methodology. The rates using the new methodology for 2016 through 2020 are not comparable to coverage rates for years before 2016, which relied on the prior methodology.

Nonetheless we can compare earlier trends to more recent ones. Estimates in the 2017 version of this annual report show WIC coverage declining from its peak of 63.5 percent in 2011 to 52.7 percent in 2015, while the 2020 report shows a gradual decline from 54.8 percent in 2016 to 50.2 percent in 2020, suggesting troubling downward trends over the last decade.

As noted, while the coverage rate has fallen across participant groups, the overall rate masks important differences in the rate for subgroups. Coverage remained lowest among pregnant people and (non-infant) children between 2016 and 2020, ending at rates of 45.6 percent and 41 percent, respectively. It’s important to ensure that more pregnant individuals get the nutritious food and services that WIC can help provide because WIC participation is associated with improved birth outcomes, and participating earlier in pregnancy is associated with decreased food insecurity.

In addition, coverage rates were lower for older eligible children in 2020, as in previous years. While more than 80 percent of eligible infants participated, only just above half of eligible 1-year-olds and fewer than a quarter of eligible 4-year-olds did. Reaching more eligible children would help provide them with more nutritious diets in crucial years of development. Moreover, longer participation improves nutritional outcomes and makes periods of food insecurity less likely while participating. Children who participate in WIC in addition to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program are also more likely to be food-secure later in life than children who only participate in SNAP.

There are also differences in how WIC reaches eligible families across race and ethnicity. Latino families in 2020 had the highest coverage rate (63.5 percent), followed by Black families (50.2 percent), families of another race or multiple races (55.9 percent), and white families (37.9 percent). With strong evidence that WIC supports healthier pregnancies and births, WIC may already be reducing racial disparities in health and food insecurity by providing food benefits and services to higher rates of families of color during the prenatal and postpartum periods.

The U.S. maternal mortality rate is over four times higher than the median maternal mortality rate of select other high-income countries, suggesting WIC has a crucial role to play for all people giving birth in the U.S. Even still, families of color are much more likely than white families to experience adverse maternal and infant health outcomesexperience adverse maternal and infant health outcomes, such as higher rates of pregnancy complications and maternal and infant mortality, due to underlying structural racism and discrimination in the nation’s health, economic, and other systems. They’re also more likely to experience food insecurity. If WIC coverage rates improved for U.S. families across races and ethnicities, it could help alleviate the nationwide maternal health crisis while also contributing to gains in racial equity in maternal and child health and food security.

Fortunately, federal and state policymakers can take steps to help WIC reach more eligible families. For nearly the past three years, USDA has given WIC administrators temporary flexibility to offer remote enrollment and services like breastfeeding support or nutrition counseling, which have proven to be widely popular among participants and staff. But the program’s underlying rules still require most certification appointments to be in person.

Congress missed a chance in end-of-year legislation to permanently allow remote enrollment. While the initial flexibility will end on August 9, 2023 (90 days after the end of the public health emergency), USDA recently announced that ongoing modernization-related flexibility provided in the American Rescue Plan will allow WIC programs to offer remote certification appointments through September 2026, giving policymakers more time to enact a permanent change. In the meantime, related funding to support program outreach, modernization, and innovations could help turn around the downward trend in coverage rates.

Also, state policymakers don’t have to wait for federal action to increase WIC participation. States can use data from Medicaid and SNAP, participation in which makes people “adjunctively eligible” for WIC, to encourage non-participants to enroll. Data indicate more than 80 percent of infants and children eligible for WIC receive Medicaid or SNAP but not all of them are enrolled. States can also simplify the enrollment and renewal process to make it easier for applicants to join or continue participating in the program.

Improvements in WIC’s coverage rate will be especially important when families are struggling to keep up with food price inflation, and might lose Medicaid coverage or receive lower SNAP benefits as certain temporary COVID-related measures end. Together, state and federal measures to help more eligible people participate could increase WIC’s coverage rate and bring the program’s proven health and developmental benefits to more low-income pregnant people and young children.